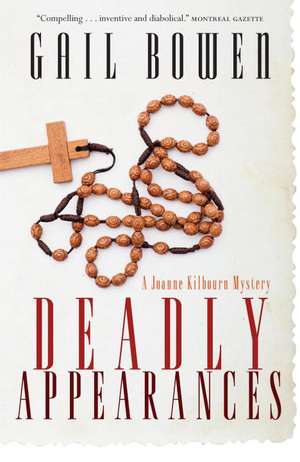

Deadly Appearances: Joanne Kilbourn Mysteries (Paperback)

Autor Gail Bowenen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2011

From the Paperback edition.

Preț: 86.08 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 129

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.47€ • 17.15$ • 13.92£

16.47€ • 17.15$ • 13.92£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780771013249

ISBN-10: 0771013248

Pagini: 279

Ilustrații: SERIES BACK ADS 1C

Dimensiuni: 132 x 201 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: McClelland & Stewart

Seria Joanne Kilbourn Mysteries (Paperback)

ISBN-10: 0771013248

Pagini: 279

Ilustrații: SERIES BACK ADS 1C

Dimensiuni: 132 x 201 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: McClelland & Stewart

Seria Joanne Kilbourn Mysteries (Paperback)

Extras

For the first seconds after Andy’s body slumped onto the searing metal of the truck bed, it seemed as if we were all encircled by a spell that froze us in the terrible moment of his fall. Suspended in time, the political people standing behind the stage, hands wrapped around plastic glasses of warm beer, kept talking politics. Craig and Julie Evanson, the perfect political couple, safely out of public view, were drinking wine coolers from bottles. Andy’s family and friends, awkward at finding themselves so publicly in the place of honour, kept sitting, small smiles in place, on the folding chairs that lined the back of the stage. The people out front kept looking expectantly at the empty space behind the podium. Waiting. Waiting.

And then chaos. Everyone wanted to get to Andy. Including me. The stage was about four and a half feet off the ground. Accessible. I stepped back a few steps, took a little run and threw myself onto the stage floor. It was when I was lying on that scorching metal, shins stinging, wind knocked out of me, chin bruised from the hit I had taken, that I saw Rick Spenser.

There was, and still is, something surreal about that moment: the famous face looming up out of nowhere. He was pulling himself up the portable metal staircase that was propped against the back of the truck bed. His body appeared in stages over the metal floor: head, shoulders and arms, torso, belly, legs, feet. He seemed huge. He was climbing those steps as if his life depended on it, and his face was shiny and red with exertion. The heat on the floor of the stage was unbearable. I could smell it. I remember thinking, very clearly, a big man like that could die in this heat, then I turned and scrambled toward Andy. The metal floor was so hot it burned the palms of my hands.

Over the loudspeaker a woman was saying, “Could a doctor please come up here?” over and over. Her voice was terrible, forlorn and empty of hope. As soon as I saw Andy, I knew there wasn’t any point in a doctor.

Andy was in front of me, and I knew he was dead. He looked crumpled ߝ all the sinew and spirit was gone. For the only time since I’d known him, he looked ߝ no other word ߝ insignificant.

The winter after my husband died I had taken a course in emergency cardiac care ߝ something to make me feel less exposed to danger, less at the mercy of the things that could kill you if you weren’t ready for them. As I turned Andy over on his back, I could hear the voice of our instructor, very young, very confident ߝ nothing would ever hurt her. “I hope none of you ladies ever have to use this, but if you do, just remember abc.” I was beginning to tremble. Airway. I took Andy’s chin between my thumb and fore finger and tilted his head back. His flesh felt clammy and flaccid, but the airway was clear. Breathing. I put my ear on his mouth, listened, and watched his chest for a sign of breathing. There was nothing. I was talking to myself. I could hear my voice, but it didn’t sound like me. “Four quick rescue breaths and then c. Check circulation.” I bent over Andy and pinched his nostrils shut. “Oh, I’m sorry, Andy. I’m sorry,” and I bent my mouth to cover his. abc ߝ but I never got to c.

There was a smell on his lips and around his mouth. It was familiar, but I couldn’t place it. Something ordinary and domestic, but there was an acrid edge to it that made me stop. Without forming the thought, I knew I had smelled danger. Then I looked toward the podium and saw Rick Spenser filling the glass from the black Thermos. I didn’t hesitate. His hands were shaking so badly he could barely hold the glass. Water was splashing down his arms and on his belly, but he must have filled his glass because he raised it to his lips. Suddenly the world became narrow and focused. All that mattered now was to keep him from drinking that water. I opened my arms and threw myself at Rick Spenser’s knees. It was a surprisingly solid hit. He fell hard, face down. He must have stunned himself because for a few moments he was very still.

The next few minutes are a jumble. The ambulance came. Spenser regained consciousness. As the attendants loaded Andy on the stretcher, Spenser sat with his legs stretched in front of him like the fat boy in the Snakes and Ladders game. When I walked over to the podium to pick up Andy’s speech portfolio, my foot brushed against his.

In the distance I could hear sirens.

That last day of Andy Boychuk’s life had started out to be one of the best. In June he had been selected leader of our provincial party, and we had planned an end-of-summer picnic so that people could eat, play a little ball and shake hands with the new leader of the Official Opposition.

Simple, wholesome pleasures. But in politics there is always subtext, even at an old-fashioned picnic, and that brilliant August day had enough subtext for a Bergman movie. Nomination fights can be intense, and Andy’s had been particularly fierce because odds were good that we would form the next government. The prize had been worth having. And for more than a few people in the park that day, watching the leadership slip into someone else’s hands had been a cruel blow. Soothing those people, making it possible for them to forgive him for winning, was Andy’s first priority at the picnic, but there was another matter too, and this one was going to need skills that weren’t taught in Political Science 100.

For years, there had been unanswered questions about Andy Boychuk’s domestic life. His wife, Eve, was odd and reclusive. There had been a dozen rumours about her strange behaviour, and now that Andy was leader we had to put those stories to rest.

So behind the homespun pleasures of concession stands selling fresh-baked pies and corn on the cob or chances on quilts and amateur oil paintings, there was a deadly serious purpose. That day we had to begin to lay to rest Andy Boychuk’s ghosts. It wasn’t going to be easy. I had driven into the park earlier that morning to check things out. Two hardmuscled young women had been stringing a sign across the base of the truck bed we were using as a stage. It said, “Andy Boychuk Appreciation Day,” and when I saw it, I crossed my fingers and said, “Let it work. Oh, please, let it be perfect.” For a while it was. The day was flawless: still, blue-skied, hot, and by noon, the fields of summer fallow we were using for parking areas were filled, and we had to ask the farmer who owned them to let us use more. All afternoon the line of cars coming down the hill continued without a break. In the picnic area, the food was hot, the drinks were cold, and the music drifted, pleasant and forgettable, from speakers hung on the trees. Everybody was in a good mood.

Especially Andy. On that August day so full of politics and sunshine and baseball, he was as happy as I had ever seen him.

I’d watched him play a couple of innings in the slo-pitch tournament, and he’d been sensational. He’d come off the field sweating and dirty and triumphant.

“The man can do no wrong today,” he’d said, beaming.

“It’s never too late, Jo. I could still be a major-leaguer.”

And I had laughed, too. “Absolutely,” I said, “but there are five thousand people here today who want to hear this terrific speech I wrote for you, and ߝ”

“And I have to sacrifice a career with the Jays to your vanity.” He grinned and wiped the sweat from his forehead with the back of his hand.

“That’s about the way I see it,” I said. “Remember that line from your acceptance speech about how it’s time to put the common good above individual ambition? Well, your chance is here. There’s one bathroom in this entire park that has a functioning hot-water tap, and Dave Micklejohn said that at three-thirty he’ll be lurking there with a fresh shirt for you, so you can get up on that stage and give the people something to tell their grandchildren about.” I looked at my watch. “You’ve got five minutes. Forget the Blue Jays. Think of the common good. The bathroom’s just over the hill ߝ a green building behind the concession stands.”

Andy laughed. “Okay, but you just wait till next year.”

“You bet,” I said, and I stood and watched as he ran up the hill, a slight figure with the slim hips and easy grace of an athlete. At the top, he stopped to talk to a man. I was too far away to see the man’s face, but I would have recognized the powerful boxer’s body anywhere. Howard Dowhanuik had been premier of our province for eleven years, leader of the Official Opposition for seven, and my friend for all that time and more. He was the man Andy succeeded in June, and there was something poignant and symbolic about seeing the once and future leaders, silhouetted against the brilliant blue of the big prairie sky. Even from a distance, it was apparent that their talk was serious and emotional, but finally the crisis seemed resolved, and Howard patted Andy’s shoulder. Then, in the blink of an eye, Andy disappeared over the top of the hill, and Howard was walking toward me, smiling.

“You look happy,” I said.

“I’ve got every reason to be,” he said. “I’m with you. The weather’s great. I managed to get over to the stage in time to hear the fiddlers and I got away before those little girls started dancing. What is it that they call themselves?”

“The Tapping Toddlers,” I said, “and I doubt if they chose the name. My guess is that the parents who let those kids wear hot-pink satin pants and sequinned bras are the ones who came up with it. Sometimes I don’t think we’ve come very far.”

“Sometimes I agree with you.” He shrugged. “Come on, Jo. It’s too nice a day to despair of the human race. Let’s go over and watch the chicken man. I’ll buy you an early supper.” I groaned. “I’ve been eating all day, but I guess the damage is already done. As my grandmother always said, ‘In for a penny, in for a pound.’” And so we walked over to the barbecue pit across the road from the stage. A man from the poultry association was grilling five hundred split broilers.

Up and down he moved, slapping sauce on the chickens with a paintbrush, reaching across the grill to adjust a piece that didn’t seem positioned right, breaking off a burning wing tip with his thick, callused fingers.

Howard’s old hawk’s face was red from the sun and the heat, but he was rapt as he watched the poultry man’s progress.

“Jo, the trouble with politics is that it doesn’t leave you time to enjoy the little things. Look at this guy ߝ I’ll bet he’s cooked two thousand chickens today. He’s a real artist. Go ahead and smile, but see, he knows just when to turn those things. That’s what I’m going to enjoy now that I’m out of it ߝ the simple pleasures.”

“Going to find time to smell the roses, are you?” I said, laughing. “Howard, you’re a fraud. Two days ago you told me that anybody who doesn’t care about politics is dead from the neck down. I don’t think you’re quite ready to trade the back rooms for a bag of briquettes.”

Across the road, the entertainment had ended and the speeches had begun. The loudspeakers squawked out something indecipherable. In the field in front of the stage, the crowd roared, and the man of simple pleasures was suddenly all politics again.

“Whoever that is onstage has really got them going,” he said.

I linked my arm through his. “Are you going to miss all this?” I asked, indicating the scene around us.

“Yeah, of course I am.”

“You could change your mind and run again, you know, or just stay around behind the scenes. Andy could use somebody who knows how to keep things from unravelling.”

“No, I wasn’t cut out to be an éminence grise ߝ lousy fringe benefits.”

The man from the poultry association was taking broilers off the grills now, grabbing the tips of the drumsticks between his thumb and index finger and giving his wrist enough of a flick to propel the chickens into an aluminum baking pan he held in his other hand.

“How about you, Jo? Have you thought any more about running? That guy who won Ian’s seat in the by-election is about as dynamic as a cow fart.”

“Not a chance, Howard. I’m happy right where I am. I think I’m over Ian’s death. The kids are great, and I finally have some time to do what I want to do. This year off from teaching is going to be heaven. And, you know, the speech writing I’m doing for Andy is going to fit in perfectly. It’ll give me some good examples for my dissertation. If I get it done in time for your birthday, I’ll give you the first copy. Want to read a scholarly treatise called ‘Saskatchewan Politics: Its Theory and Practice’?”

“God, no. I might find out that I’ve been doing it wrong all along.” He looked at his watch. “Time for the main event. Let’s grab a plate of chicken. Incidentally, guess who I strong-armed into giving the warm-up speech before Andy comes out.”

“His wife?”

Howard winced. “I’m not a miracle worker, Jo. Although Eve is here today. I saw her in that little trailer thing they’ve got in back of the stage for Andy’s family and the entertainment people.”

“How did she look?”

“The way she always looks when she gets dragged to one of these things ߝ like someone just beamed her down. Anyway, you’re wrong. Eve isn’t introducing Andy. Guess again.”

“Not Craig Evanson.”

Howard pointed at the stage across the road and smiled.

“There he is at the podium.”

“You underestimate yourself,” I said. “You are a miracle worker, especially after that terrible interview last night on Lachlan MacNeil’s show. I can’t believe Andy isn’t more worried about it. I tried to talk to him, you know, but he says people will forget about it in a week, and besides, since everybody knows what MacNeil’s like, no one’ll take it seriously.”

“Julie Evanson’s taking it seriously,” Howard said grimly. “She tracked me down this morning and told me Andy should either resign or be castrated ߝ I think she felt that as the aggrieved party, Craig should have the option of selecting the punishment that fit the crime.”

“Well,” I said, “if Craig decides on castration, I might volunteer to hold his coat. Didn’t you ever take Andy out behind the barn and tell him the boys and girls of the press can play rough? He should have known better. Craig and Julie had just about gotten over Craig’s losing the leadership and what does Andy do? He tells Canadians from coast-to-coast that if we’re elected, Craig had better forget about being deputy premier or attorney general because he’s too dumb.”

“Be fair, Jo, that shithead MacNeil really drove Andy into a corner. All Andy said was that when we’re elected he’ll find a job for Craig that’s suitable to his talents. And you know as well as I do that Craig isn’t the brightest light on the porch.”

“Oh, God, Howard, I know. We all know Craig’s limited, and I’ll even grant you that he shouldn’t be deputy premier or a-g. But he’s a decent man, and more to the point, he almost won. Andy only beat him by ten votes. That’s not much. I wish MacNeil hadn’t made Andy run through that list of all the serious jobs and say Craig wasn’t up to any of them. And I really wish that Andy hadn’t risen to the bait when that twerp asked him to name a job Craig would be capable of handling. Minister of the Family? My dogs could handle that one. No wonder Julie was mad. Speaking of . . . we’d better get over there. Julie’s always been able to look at a crowd of five thousand people and know exactly who wasn’t there to hear her Craig.”

The man from the poultry association opened a metal ice chest, pulled out the last bags of fresh broilers and began laying them on the grills. It was a little after four o’clock. The ballplayers were coming off the diamonds tired and hungry. The poultry man wouldn’t be taking any chickens back to the city with him tonight. For a moment Howard was still, watching, absorbed. Then he shrugged and grabbed my hand.

“Let’s go, lady,” he said. Hand in hand we crossed the road and moved through the crowd toward the stage. When we got close, Dave Micklejohn ran out to meet us. He had been Andy’s executive assistant for as long as I could remember, and his devotion to Andy was as fierce as it was absolute. No one knew how old Dave was ߝ certainly he was past the age suggested for the retirement of civil servants, but he had such energy that his age was irrelevant. He was fussy, condescending and irreplaceable.

That day, as always, he was carrying a clipboard. Also, as always, he was immaculate. He was wearing white, white shorts and a T-shirt imprinted with a picture of Jean- Paul Sartre.

“I like your shirt,” I said.

“I tell everyone he’s running for us in the south end of the province,” he said. “You two were certainly no help. I run my buns off getting that bunch up there at the same time ߝ” he waved at Andy’s family and friends, sitting like kindergarten children on folding chairs along the back of the stage “ߝ and you two vanish into thin air.”

“Howard wanted to watch his hero, the chicken man,” I said. “Anyway, we’re here now. Did you find Andy to give him the fresh shirt?”

“Of course,” he said, “I’m a Virgo. I know the importance of details.”

I reached over and touched his hand. “Dave, don’t be mad at us. You’ve done a wonderful job. How did you ever get Eve to come?”

I could see him thaw. Then, unexpectedly, he looked down, embarrassed. “Well, it wasn’t easy. I had to agree to sneak a piece of quartz onto the podium today. She says the electromagnetic field from the crystal will combine with Andy’s electrical field to erase negativity and recharge energy stores.”

“Oh, God, Dave, no.”

He squared his shoulders, and Sartre rippled defiantly on his chest. “She’s here, isn’t she? And look.” He held up a sliver of rose quartz that glittered benignly in the sunlight. “You can put these things in water, you know. Eve says they charge up the people drinking it and bring them into harmony with their environment. Actually, we had quite a nice talk about it.”

“Why don’t you make Roma a nice cup of water on the rocks?” I pointed to the far end of the stage, where Andy’s mother, Roma, was sitting stiffly, as far away as she could get from her daughter-in-law. “She looks like she could use some harmonizing. Actually, what we probably need is a slab of quartz dropped in the water supply for the whole city ߝ take care of all our problems.” Beside me, Howard gazed innocently in the direction of the ball diamonds.

Dave snapped the clip on his clipboard. “You don’t have to be such a bitch, Jo. In fact, if you could manage to let up a little, I could tell you about our real triumph.” He smoothed the crease of his shorts and looked at me. “Rick Spenser’s here today.”

I was impressed. “What’s he doing here? I know this is big stuff for us, but it’s penny ante for the networks. Why would those guys at cvt send their top political commentator to cover a little picnic on the prairies?”

“I don’t know,” said Dave, “but I’m ecstatic. There are a lot of nice visuals here today ߝ all the little kids guessing how many jellybeans are in the jar, and the old geezers throwing horseshoes and reminiscing. How many points do you think all this heartland charm will be worth in the polls, Jo?”

“You’ll have to ask Howard. He’s the expert.”

But Howard was heading behind the stage, where the major players, as they liked to think of themselves, were talking politics and drinking warm beer out of plastic cups. It didn’t matter. We couldn’t have heard Howard anyway because Craig Evanson had finished, Andy was walking across the stage to the podium, and the crowd was on its feet. They had waited all afternoon for this, the moment when Andy would stand before them. Now he was here and they were wild ߝ clapping their hands together in a ragged attempt at rhythm and calling his name again and again.

“Andy, Andy, Andy.” Two distinct syllables, regular as heartbeats until throats grew hoarse and the beat became thready. We could see Andy clearly now. He was wearing an opennecked shirt the colour of the sky, and when he saw Dave and me, he grinned and waved his baseball cap in the air. The crowd cheered as if he had turned stone to gold. Finally, Andy raised his hands to quiet them, then he turned toward Dave and me and made a drinking gesture.

“Water,” I said.

“Taken care of,” said Dave, and he ran behind the stage and came back carrying a tray with a glass and a black thermal pitcher. When he went by me, he stopped and pointed to a little hand-lettered sign he’d taped to the side of the Thermos: “for the use of andy boychuk only. all others drink this and die.”

I laughed. “So much for the brotherhood of the common man.”

Dave passed the tray to the woman who was acting as emcee for the entertainment. She was a big woman, wearing a flower-printed dress. I remember thinking all afternoon that she must have been suffering from the heat. She handed Andy the tray with a pretty little flourish, and he took it with a gallant gesture.

I moved to the side of the stage. There was a patch of shade there, and it gave me a clear view of Andy and of the crowd. They were arranging themselves for the speech ߝ trying to find a cool spot on their beach towels, pouring watery, tepid drinks out of Thermoses, slipping kids a couple of dollars for the amusement booths that had been set up. Afterward, even the police were astounded at how few people had any real memory of what they saw in those last moments. But I saw, and I remembered.

Andy filled his glass from the Thermos, drank the water, all of it, then opened the blue leather folder that contained the speech I’d written for him. It was a sequence I’d watched a hundred times. But this time, instead of sliding his thumbs to the top of the podium, leaning toward the audience and beginning to speak, he turned to look at Dave and me. He was still smiling, but then something dark and private flickered across his face. He looked perplexed and sad, the way he did when someone asked him a question that revealed real ugliness. Then he turned toward the back of the stage and collapsed. From the time he turned until the time he fell was, I am sure, less than five seconds. It seemed like a lifetime.

And then chaos. Everyone wanted to get to Andy. Including me. The stage was about four and a half feet off the ground. Accessible. I stepped back a few steps, took a little run and threw myself onto the stage floor. It was when I was lying on that scorching metal, shins stinging, wind knocked out of me, chin bruised from the hit I had taken, that I saw Rick Spenser.

There was, and still is, something surreal about that moment: the famous face looming up out of nowhere. He was pulling himself up the portable metal staircase that was propped against the back of the truck bed. His body appeared in stages over the metal floor: head, shoulders and arms, torso, belly, legs, feet. He seemed huge. He was climbing those steps as if his life depended on it, and his face was shiny and red with exertion. The heat on the floor of the stage was unbearable. I could smell it. I remember thinking, very clearly, a big man like that could die in this heat, then I turned and scrambled toward Andy. The metal floor was so hot it burned the palms of my hands.

Over the loudspeaker a woman was saying, “Could a doctor please come up here?” over and over. Her voice was terrible, forlorn and empty of hope. As soon as I saw Andy, I knew there wasn’t any point in a doctor.

Andy was in front of me, and I knew he was dead. He looked crumpled ߝ all the sinew and spirit was gone. For the only time since I’d known him, he looked ߝ no other word ߝ insignificant.

The winter after my husband died I had taken a course in emergency cardiac care ߝ something to make me feel less exposed to danger, less at the mercy of the things that could kill you if you weren’t ready for them. As I turned Andy over on his back, I could hear the voice of our instructor, very young, very confident ߝ nothing would ever hurt her. “I hope none of you ladies ever have to use this, but if you do, just remember abc.” I was beginning to tremble. Airway. I took Andy’s chin between my thumb and fore finger and tilted his head back. His flesh felt clammy and flaccid, but the airway was clear. Breathing. I put my ear on his mouth, listened, and watched his chest for a sign of breathing. There was nothing. I was talking to myself. I could hear my voice, but it didn’t sound like me. “Four quick rescue breaths and then c. Check circulation.” I bent over Andy and pinched his nostrils shut. “Oh, I’m sorry, Andy. I’m sorry,” and I bent my mouth to cover his. abc ߝ but I never got to c.

There was a smell on his lips and around his mouth. It was familiar, but I couldn’t place it. Something ordinary and domestic, but there was an acrid edge to it that made me stop. Without forming the thought, I knew I had smelled danger. Then I looked toward the podium and saw Rick Spenser filling the glass from the black Thermos. I didn’t hesitate. His hands were shaking so badly he could barely hold the glass. Water was splashing down his arms and on his belly, but he must have filled his glass because he raised it to his lips. Suddenly the world became narrow and focused. All that mattered now was to keep him from drinking that water. I opened my arms and threw myself at Rick Spenser’s knees. It was a surprisingly solid hit. He fell hard, face down. He must have stunned himself because for a few moments he was very still.

The next few minutes are a jumble. The ambulance came. Spenser regained consciousness. As the attendants loaded Andy on the stretcher, Spenser sat with his legs stretched in front of him like the fat boy in the Snakes and Ladders game. When I walked over to the podium to pick up Andy’s speech portfolio, my foot brushed against his.

In the distance I could hear sirens.

That last day of Andy Boychuk’s life had started out to be one of the best. In June he had been selected leader of our provincial party, and we had planned an end-of-summer picnic so that people could eat, play a little ball and shake hands with the new leader of the Official Opposition.

Simple, wholesome pleasures. But in politics there is always subtext, even at an old-fashioned picnic, and that brilliant August day had enough subtext for a Bergman movie. Nomination fights can be intense, and Andy’s had been particularly fierce because odds were good that we would form the next government. The prize had been worth having. And for more than a few people in the park that day, watching the leadership slip into someone else’s hands had been a cruel blow. Soothing those people, making it possible for them to forgive him for winning, was Andy’s first priority at the picnic, but there was another matter too, and this one was going to need skills that weren’t taught in Political Science 100.

For years, there had been unanswered questions about Andy Boychuk’s domestic life. His wife, Eve, was odd and reclusive. There had been a dozen rumours about her strange behaviour, and now that Andy was leader we had to put those stories to rest.

So behind the homespun pleasures of concession stands selling fresh-baked pies and corn on the cob or chances on quilts and amateur oil paintings, there was a deadly serious purpose. That day we had to begin to lay to rest Andy Boychuk’s ghosts. It wasn’t going to be easy. I had driven into the park earlier that morning to check things out. Two hardmuscled young women had been stringing a sign across the base of the truck bed we were using as a stage. It said, “Andy Boychuk Appreciation Day,” and when I saw it, I crossed my fingers and said, “Let it work. Oh, please, let it be perfect.” For a while it was. The day was flawless: still, blue-skied, hot, and by noon, the fields of summer fallow we were using for parking areas were filled, and we had to ask the farmer who owned them to let us use more. All afternoon the line of cars coming down the hill continued without a break. In the picnic area, the food was hot, the drinks were cold, and the music drifted, pleasant and forgettable, from speakers hung on the trees. Everybody was in a good mood.

Especially Andy. On that August day so full of politics and sunshine and baseball, he was as happy as I had ever seen him.

I’d watched him play a couple of innings in the slo-pitch tournament, and he’d been sensational. He’d come off the field sweating and dirty and triumphant.

“The man can do no wrong today,” he’d said, beaming.

“It’s never too late, Jo. I could still be a major-leaguer.”

And I had laughed, too. “Absolutely,” I said, “but there are five thousand people here today who want to hear this terrific speech I wrote for you, and ߝ”

“And I have to sacrifice a career with the Jays to your vanity.” He grinned and wiped the sweat from his forehead with the back of his hand.

“That’s about the way I see it,” I said. “Remember that line from your acceptance speech about how it’s time to put the common good above individual ambition? Well, your chance is here. There’s one bathroom in this entire park that has a functioning hot-water tap, and Dave Micklejohn said that at three-thirty he’ll be lurking there with a fresh shirt for you, so you can get up on that stage and give the people something to tell their grandchildren about.” I looked at my watch. “You’ve got five minutes. Forget the Blue Jays. Think of the common good. The bathroom’s just over the hill ߝ a green building behind the concession stands.”

Andy laughed. “Okay, but you just wait till next year.”

“You bet,” I said, and I stood and watched as he ran up the hill, a slight figure with the slim hips and easy grace of an athlete. At the top, he stopped to talk to a man. I was too far away to see the man’s face, but I would have recognized the powerful boxer’s body anywhere. Howard Dowhanuik had been premier of our province for eleven years, leader of the Official Opposition for seven, and my friend for all that time and more. He was the man Andy succeeded in June, and there was something poignant and symbolic about seeing the once and future leaders, silhouetted against the brilliant blue of the big prairie sky. Even from a distance, it was apparent that their talk was serious and emotional, but finally the crisis seemed resolved, and Howard patted Andy’s shoulder. Then, in the blink of an eye, Andy disappeared over the top of the hill, and Howard was walking toward me, smiling.

“You look happy,” I said.

“I’ve got every reason to be,” he said. “I’m with you. The weather’s great. I managed to get over to the stage in time to hear the fiddlers and I got away before those little girls started dancing. What is it that they call themselves?”

“The Tapping Toddlers,” I said, “and I doubt if they chose the name. My guess is that the parents who let those kids wear hot-pink satin pants and sequinned bras are the ones who came up with it. Sometimes I don’t think we’ve come very far.”

“Sometimes I agree with you.” He shrugged. “Come on, Jo. It’s too nice a day to despair of the human race. Let’s go over and watch the chicken man. I’ll buy you an early supper.” I groaned. “I’ve been eating all day, but I guess the damage is already done. As my grandmother always said, ‘In for a penny, in for a pound.’” And so we walked over to the barbecue pit across the road from the stage. A man from the poultry association was grilling five hundred split broilers.

Up and down he moved, slapping sauce on the chickens with a paintbrush, reaching across the grill to adjust a piece that didn’t seem positioned right, breaking off a burning wing tip with his thick, callused fingers.

Howard’s old hawk’s face was red from the sun and the heat, but he was rapt as he watched the poultry man’s progress.

“Jo, the trouble with politics is that it doesn’t leave you time to enjoy the little things. Look at this guy ߝ I’ll bet he’s cooked two thousand chickens today. He’s a real artist. Go ahead and smile, but see, he knows just when to turn those things. That’s what I’m going to enjoy now that I’m out of it ߝ the simple pleasures.”

“Going to find time to smell the roses, are you?” I said, laughing. “Howard, you’re a fraud. Two days ago you told me that anybody who doesn’t care about politics is dead from the neck down. I don’t think you’re quite ready to trade the back rooms for a bag of briquettes.”

Across the road, the entertainment had ended and the speeches had begun. The loudspeakers squawked out something indecipherable. In the field in front of the stage, the crowd roared, and the man of simple pleasures was suddenly all politics again.

“Whoever that is onstage has really got them going,” he said.

I linked my arm through his. “Are you going to miss all this?” I asked, indicating the scene around us.

“Yeah, of course I am.”

“You could change your mind and run again, you know, or just stay around behind the scenes. Andy could use somebody who knows how to keep things from unravelling.”

“No, I wasn’t cut out to be an éminence grise ߝ lousy fringe benefits.”

The man from the poultry association was taking broilers off the grills now, grabbing the tips of the drumsticks between his thumb and index finger and giving his wrist enough of a flick to propel the chickens into an aluminum baking pan he held in his other hand.

“How about you, Jo? Have you thought any more about running? That guy who won Ian’s seat in the by-election is about as dynamic as a cow fart.”

“Not a chance, Howard. I’m happy right where I am. I think I’m over Ian’s death. The kids are great, and I finally have some time to do what I want to do. This year off from teaching is going to be heaven. And, you know, the speech writing I’m doing for Andy is going to fit in perfectly. It’ll give me some good examples for my dissertation. If I get it done in time for your birthday, I’ll give you the first copy. Want to read a scholarly treatise called ‘Saskatchewan Politics: Its Theory and Practice’?”

“God, no. I might find out that I’ve been doing it wrong all along.” He looked at his watch. “Time for the main event. Let’s grab a plate of chicken. Incidentally, guess who I strong-armed into giving the warm-up speech before Andy comes out.”

“His wife?”

Howard winced. “I’m not a miracle worker, Jo. Although Eve is here today. I saw her in that little trailer thing they’ve got in back of the stage for Andy’s family and the entertainment people.”

“How did she look?”

“The way she always looks when she gets dragged to one of these things ߝ like someone just beamed her down. Anyway, you’re wrong. Eve isn’t introducing Andy. Guess again.”

“Not Craig Evanson.”

Howard pointed at the stage across the road and smiled.

“There he is at the podium.”

“You underestimate yourself,” I said. “You are a miracle worker, especially after that terrible interview last night on Lachlan MacNeil’s show. I can’t believe Andy isn’t more worried about it. I tried to talk to him, you know, but he says people will forget about it in a week, and besides, since everybody knows what MacNeil’s like, no one’ll take it seriously.”

“Julie Evanson’s taking it seriously,” Howard said grimly. “She tracked me down this morning and told me Andy should either resign or be castrated ߝ I think she felt that as the aggrieved party, Craig should have the option of selecting the punishment that fit the crime.”

“Well,” I said, “if Craig decides on castration, I might volunteer to hold his coat. Didn’t you ever take Andy out behind the barn and tell him the boys and girls of the press can play rough? He should have known better. Craig and Julie had just about gotten over Craig’s losing the leadership and what does Andy do? He tells Canadians from coast-to-coast that if we’re elected, Craig had better forget about being deputy premier or attorney general because he’s too dumb.”

“Be fair, Jo, that shithead MacNeil really drove Andy into a corner. All Andy said was that when we’re elected he’ll find a job for Craig that’s suitable to his talents. And you know as well as I do that Craig isn’t the brightest light on the porch.”

“Oh, God, Howard, I know. We all know Craig’s limited, and I’ll even grant you that he shouldn’t be deputy premier or a-g. But he’s a decent man, and more to the point, he almost won. Andy only beat him by ten votes. That’s not much. I wish MacNeil hadn’t made Andy run through that list of all the serious jobs and say Craig wasn’t up to any of them. And I really wish that Andy hadn’t risen to the bait when that twerp asked him to name a job Craig would be capable of handling. Minister of the Family? My dogs could handle that one. No wonder Julie was mad. Speaking of . . . we’d better get over there. Julie’s always been able to look at a crowd of five thousand people and know exactly who wasn’t there to hear her Craig.”

The man from the poultry association opened a metal ice chest, pulled out the last bags of fresh broilers and began laying them on the grills. It was a little after four o’clock. The ballplayers were coming off the diamonds tired and hungry. The poultry man wouldn’t be taking any chickens back to the city with him tonight. For a moment Howard was still, watching, absorbed. Then he shrugged and grabbed my hand.

“Let’s go, lady,” he said. Hand in hand we crossed the road and moved through the crowd toward the stage. When we got close, Dave Micklejohn ran out to meet us. He had been Andy’s executive assistant for as long as I could remember, and his devotion to Andy was as fierce as it was absolute. No one knew how old Dave was ߝ certainly he was past the age suggested for the retirement of civil servants, but he had such energy that his age was irrelevant. He was fussy, condescending and irreplaceable.

That day, as always, he was carrying a clipboard. Also, as always, he was immaculate. He was wearing white, white shorts and a T-shirt imprinted with a picture of Jean- Paul Sartre.

“I like your shirt,” I said.

“I tell everyone he’s running for us in the south end of the province,” he said. “You two were certainly no help. I run my buns off getting that bunch up there at the same time ߝ” he waved at Andy’s family and friends, sitting like kindergarten children on folding chairs along the back of the stage “ߝ and you two vanish into thin air.”

“Howard wanted to watch his hero, the chicken man,” I said. “Anyway, we’re here now. Did you find Andy to give him the fresh shirt?”

“Of course,” he said, “I’m a Virgo. I know the importance of details.”

I reached over and touched his hand. “Dave, don’t be mad at us. You’ve done a wonderful job. How did you ever get Eve to come?”

I could see him thaw. Then, unexpectedly, he looked down, embarrassed. “Well, it wasn’t easy. I had to agree to sneak a piece of quartz onto the podium today. She says the electromagnetic field from the crystal will combine with Andy’s electrical field to erase negativity and recharge energy stores.”

“Oh, God, Dave, no.”

He squared his shoulders, and Sartre rippled defiantly on his chest. “She’s here, isn’t she? And look.” He held up a sliver of rose quartz that glittered benignly in the sunlight. “You can put these things in water, you know. Eve says they charge up the people drinking it and bring them into harmony with their environment. Actually, we had quite a nice talk about it.”

“Why don’t you make Roma a nice cup of water on the rocks?” I pointed to the far end of the stage, where Andy’s mother, Roma, was sitting stiffly, as far away as she could get from her daughter-in-law. “She looks like she could use some harmonizing. Actually, what we probably need is a slab of quartz dropped in the water supply for the whole city ߝ take care of all our problems.” Beside me, Howard gazed innocently in the direction of the ball diamonds.

Dave snapped the clip on his clipboard. “You don’t have to be such a bitch, Jo. In fact, if you could manage to let up a little, I could tell you about our real triumph.” He smoothed the crease of his shorts and looked at me. “Rick Spenser’s here today.”

I was impressed. “What’s he doing here? I know this is big stuff for us, but it’s penny ante for the networks. Why would those guys at cvt send their top political commentator to cover a little picnic on the prairies?”

“I don’t know,” said Dave, “but I’m ecstatic. There are a lot of nice visuals here today ߝ all the little kids guessing how many jellybeans are in the jar, and the old geezers throwing horseshoes and reminiscing. How many points do you think all this heartland charm will be worth in the polls, Jo?”

“You’ll have to ask Howard. He’s the expert.”

But Howard was heading behind the stage, where the major players, as they liked to think of themselves, were talking politics and drinking warm beer out of plastic cups. It didn’t matter. We couldn’t have heard Howard anyway because Craig Evanson had finished, Andy was walking across the stage to the podium, and the crowd was on its feet. They had waited all afternoon for this, the moment when Andy would stand before them. Now he was here and they were wild ߝ clapping their hands together in a ragged attempt at rhythm and calling his name again and again.

“Andy, Andy, Andy.” Two distinct syllables, regular as heartbeats until throats grew hoarse and the beat became thready. We could see Andy clearly now. He was wearing an opennecked shirt the colour of the sky, and when he saw Dave and me, he grinned and waved his baseball cap in the air. The crowd cheered as if he had turned stone to gold. Finally, Andy raised his hands to quiet them, then he turned toward Dave and me and made a drinking gesture.

“Water,” I said.

“Taken care of,” said Dave, and he ran behind the stage and came back carrying a tray with a glass and a black thermal pitcher. When he went by me, he stopped and pointed to a little hand-lettered sign he’d taped to the side of the Thermos: “for the use of andy boychuk only. all others drink this and die.”

I laughed. “So much for the brotherhood of the common man.”

Dave passed the tray to the woman who was acting as emcee for the entertainment. She was a big woman, wearing a flower-printed dress. I remember thinking all afternoon that she must have been suffering from the heat. She handed Andy the tray with a pretty little flourish, and he took it with a gallant gesture.

I moved to the side of the stage. There was a patch of shade there, and it gave me a clear view of Andy and of the crowd. They were arranging themselves for the speech ߝ trying to find a cool spot on their beach towels, pouring watery, tepid drinks out of Thermoses, slipping kids a couple of dollars for the amusement booths that had been set up. Afterward, even the police were astounded at how few people had any real memory of what they saw in those last moments. But I saw, and I remembered.

Andy filled his glass from the Thermos, drank the water, all of it, then opened the blue leather folder that contained the speech I’d written for him. It was a sequence I’d watched a hundred times. But this time, instead of sliding his thumbs to the top of the podium, leaning toward the audience and beginning to speak, he turned to look at Dave and me. He was still smiling, but then something dark and private flickered across his face. He looked perplexed and sad, the way he did when someone asked him a question that revealed real ugliness. Then he turned toward the back of the stage and collapsed. From the time he turned until the time he fell was, I am sure, less than five seconds. It seemed like a lifetime.

Notă biografică

GAIL BOWEN's Joanne Kilbourn mysteries have made her one of Canada's most popular crime-fiction writers. The first book in the series, Deadly Appearances (1990), was nominated for the W.H. SmithBooks in Canada Award for best first novel. It was followed by Murder at the Mendel (1991), The Wandering Soul Murders (1992), A Colder Kind of Death (which won the Arthur Ellis Award for best crime novel of 1995), A Killing Spring (1996), Verdict in Blood (1998), Burying Ariel (2000), The Glass Coffin (2002), The Last Good Day (2004), and The Endless Knot (2006). Bowen has also written five plays that have been produced across Canada, and one, The World According to Charlie D, for CBC Radio. Now retired from teaching at the First Nations University, Bowen lives in Regina.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Add Gail Bowen to the growing, long list of Canadians turning out superior mystery stories…Ms. Bowen charms the reader with a compelling heroine, some intriguing side figures and a suitably murky mystery, and combines it all with fine writing and acceptable surprises along the way.”

–The Whig-Standard, Kingston

“In Joanne Kilbourn, Gail Bowen has created a narrator who is bright, thoughtful, wryly entertaining, and warm without being sappy…I found this a very hard book to put down.”

–Gary Draper, Books in Canada

From the Paperback edition.

–The Whig-Standard, Kingston

“In Joanne Kilbourn, Gail Bowen has created a narrator who is bright, thoughtful, wryly entertaining, and warm without being sappy…I found this a very hard book to put down.”

–Gary Draper, Books in Canada

From the Paperback edition.