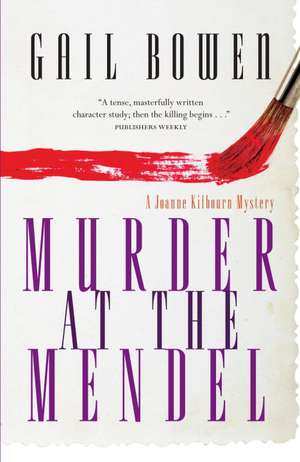

Murder at the Mendel: Joanne Kilbourn Mysteries (Paperback)

Autor Gail Bowenen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2011

From the Paperback edition.

Preț: 96.67 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 145

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.50€ • 19.26$ • 15.64£

18.50€ • 19.26$ • 15.64£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780771013218

ISBN-10: 0771013213

Pagini: 208

Dimensiuni: 132 x 201 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: McClelland & Stewart

Seria Joanne Kilbourn Mysteries (Paperback)

ISBN-10: 0771013213

Pagini: 208

Dimensiuni: 132 x 201 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: McClelland & Stewart

Seria Joanne Kilbourn Mysteries (Paperback)

Notă biografică

GAIL BOWEN's Joanne Kilbourn mysteries have made her one of Canada's most popular crime-fiction writers. The first book in the series, Deadly Appearances (1990), was nominated for the W.H. SmithBooks in Canada Award for best first novel. It was followed by Murder at the Mendel (1991), The Wandering Soul Murders (1992), A Colder Kind of Death (which won the Arthur Ellis Award for best crime novel of 1995), A Killing Spring (1996), Verdict in Blood (1998), Burying Ariel (2000), The Glass Coffin (2002), The Last Good Day (2004), and The Endless Knot (2006). Bowen has also written five plays that have been produced across Canada, and one, The World According to Charlie D, for CBC Radio. Now retired from teaching at the First Nations University, Bowen lives in Regina.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

If I hadn’t gone back to change my shoes, it would have been me instead of Izaak Levin who found them dying. But halfway to the Loves’ cottage I started worrying that shoes with heels would make me too tall to dance with, and by the time I got back to the Loves’, Izaak was standing in their doorway with the dazed look of a man on the edge of shock. When I pushed past him into the cottage, I saw why.

I was fifteen years old, and I had never seen a dead man, but I knew Desmond Love was dead. He was sitting in his place at the dining-room table, but his head lolled back on his neck as if something critical had come loose, and his mouth hung open as if he were sleeping or screaming. His wife, Nina, was in the chair across from him. She was always full of grace, and she had fallen so that her head rested against the curve of her arm as it lay on the table. She was beautiful, but her skin was waxen, and I could hear the rattle of her breathing in that quiet room. My friend Sally was lying on the floor. She had vomited; she was pale and her breathing was laboured, but I knew she wouldn’t die. She was thirteen years old, and you don’t die when you’re thirteen.

It was Nina I went to. My relationship with my own mother had never been easy, and Nina had been my refuge for as long as I could remember. I took her in my arms and began to cry and call her name. Izaak Levin was still standing in the doorway, but seeing me with Nina seemed to jolt him back to reality.

“Joanne, you have to get your father. We need a doctor here,” he said.

My legs felt heavy, the way they do in a dream when you try to run and you can’t, but somehow I got to our cottage and brought my father. He was a methodical and reassuring man, and as I watched him taking pulses, looking into pupils, checking breathing, I felt better.

“What happened?” he asked Izaak Levin.

Izaak shook his head. When he spoke, his voice was dead with disbelief. “I don’t know. I took the boat over to town for a drink before dinner. When I got back, I found them like this.” He pointed to a half-filled martini pitcher on the table. At Sally’s place there was a glass with an inch of soft drink in the bottom. “He must have put it in the drinks. I guess he decided it wasn’t worth going on, and he wanted to take them with him.”

There was no need to explain the pronouns. My father and I knew what he meant. At the beginning of the summer Desmond Love had suffered a stroke that had slurred his speech, paralyzed his right side and, most seriously, stilled his hand. He was forty years old, a bold and innovative maker of art and a handsome and immensely physical man. It was believable that, in his rage at the ravages of the stroke, he would kill himself, and so I stored away Izaak’s explanation.

I stored it away in the same place I stored the other memories of that night: the animal sound of retching Nina made after my father forced the ipecac into her mouth. The silence broken only by a loon’s cry as my father and Izaak carried the Loves, one by one, down to the motorboat at the dock. The blaze of the sunset on the lake as my father wrapped Nina and Sally in the blankets they kept in the boat for picnics. The terrible emptiness in Desmond Love’s eyes as they looked at the September sky.

And then my father, standing in the boat, looking at me on the dock, “Joanne, you’re old enough to know the truth here: Sally will be all right, but Des is dead and I’m not sure about Nina’s chances. It’ll be better for you later if you don’t ride in this boat tonight.” His voice was steady, but there were tears in his eyes. Desmond Love had been his best friend since they were boys. “I want you to go back home and wait for me. Just tell your mother there’s been an emergency. Don’t tell her . . .”

“The truth.” I finished the sentence for him. The truth would make my mother start drinking. So would a lie. It never took much.

“Don’t let Nina die,” I said in an odd, strangled voice.

“I’ll do all I can,” he said, and then the quiet of the night was shattered by the roar of the outboard motor; the air was filled with the smell of gasoline, and the boat, low in the water from its terrible cargo, began to move across the lake into the brilliant gold of the sunset. It was the summer of 1958, and I was alone on the dock, waiting.

* * *

Thirty-two years later I was walking across the bridge that links the university community to the city of Saskatoon. It was the night of the winter solstice. The sky was high and starless, and there was a bone-chilling wind blowing down the South Saskatchewan River from the north. I was on my way to the opening of an exhibition of the work of Sally Love. As soon as I turned onto Spadina Crescent, I could see the bright letters of her name on the silk banners suspended over the entrance to the Mendel Gallery: Sally Love. Sally Love. Sally Love. There was something festive and celebratory about those paint-box colours, but as I got closer I saw there were other signs, too, and some of them weren’t so pretty. These signs were mounted on stakes held by people whose faces shone with zeal, and their crude lettering seemed to pulse with indignation: “Filth Belongs in Toilets Not on Walls,” “Jail Pornographers,” “No Room for Love Here” and one that said simply, “Bitch.”

A crowd had gathered. Some people were attempting a counterattack, and every so often a voice, thin and self-conscious in the winter air, would raise itself in a tentative defence: “What about freedom of the arts?” “We’re not a police state yet!” “The only real obscenity is censorship.”

A tv crew had set up under the lights of the entrance and they were interviewing a soft-looking man in a green tuque with the Hilltops logo and a nylon ski jacket that said “Silver Broom: Saskatoon ’90.” The man was one of our city councillors, and as I walked up I could hear his spiritless baritone spinning out the clichés for the ten o’clock news: “Community standards . . . public property . . . our children’s innocence . . . privacy of the home . . .” The councillor’s name was Hank Mewhort, and years before I had been at a political fundraiser where he had dressed as a leprechaun to deliver the financial appeal. As I walked carefully around the camera crew, Hank’s sanctimonious bleat followed me. I had liked him better as a leprechaun.

When I handed my invitation to a commissionaire posted at the entrance, he checked my name off on a list and opened the gallery door for me. As I started through, I felt a sharp blow in the middle of my back. I turned and found myself facing a fresh-faced woman with a sweet and vacant smile.

She was grasping her sign so the shaft was in front of her like a broadsword. She came at me again, but then, very quickly, a city cop grabbed her from behind and led her off into the night. She was still smiling. Her sign lay on the concrete in front of me, its message carefully spelled out in indelible marker the colour of dried blood: “The Wages of Sin is Death.” I shuddered and pulled my coat tight around me. Inside, all was light and airiness and civility. People dressed in holiday evening clothes greeted one another in the reverent tones Canadians use at cultural events. A Douglas fir, its boughs luminous with yellow silk bows, filled the air with the smell of Christmas. In front of the tree was an easel with a handsome poster announcing the Sally Love exhibition. Propped discreetly against it was a small placard stating that Erotobiography was in Gallery III at the rear of the building and that patrons must be eighteen years of age to be admitted.

Very prim. Very innocent. But this small addendum to Sally’s show had eclipsed everything else. To the left of the Douglas fir, a wall plastered with newspaper clippings told the story: Erotobiography consisted of seven pictures Sally Love had painted to record her sexual experiences.

All the pictures were explicit, but the one that had caused the furor was a fresco. A fresco, the local paper noted sternly, is permanent. The colour in a fresco does not rest on the surface; it sinks into and becomes part of the wall. And what Sally Love had chosen to sink into the wall of the publicly owned Mendel Gallery was a painting of the sexual parts of all the people with whom she had been intimate. Erotobio - graphy. According to the newspaper, there were one hundred individual entries, and a handful of the genitalia were female. Nonetheless, community standards being what they are, the work was known by everyone as the Penis Painting.

The exhibition that was opening that night was a large one. Several of the pictures on loan from major galleries throughout North America had been heralded as altering the direction of contemporary art; many of the paintings had been praised for their psychological insights or their technical virtuosity. None of that seemed to matter much.

It was the penises that had prompted the people outside to leave their warm living rooms and clutch the shafts of picket signs in their mittened hands. It was the penises the handsome men and women exchanging soft words in the foyer had come to see. As I walked toward the wing where Nina Love and I had agreed to meet, I was smiling. I had to admit that I wanted to see the penises, too. The rest was just foreplay.

The south wing of the Mendel Gallery is a conservatory, a place where you can find green and flowering things even when the temperature sticks at forty below for weeks on end. When I stepped through the door, the moisture and the warmth and the fragrance enveloped me, and for a moment I stood there and let the cold and the tension flow out of my body. Nina Love was sitting on a bench in front of a blazing display of amaryllis, azalea and bird of paradise. She had a compact cupped in her hand, and her attention was wholly focused on her reflection. It was, I thought sadly, becoming her characteristic gesture.

That night as I was getting ready for Sally’s opening, I’d heard the actress Diane Keaton answer a radio interviewer’s question about how she faced aging. “You have to be very brave,” she’d said, and I’d thought of Nina. Much as I cared for her I had to admit that Nina Love wasn’t being very brave about growing older.

Until Thanksgiving, when she had come to Saskatoon to help care for her granddaughter, Nina and I had kept in touch mostly through letters and phone calls. I’d seen her only on those rare occasions when I was in Toronto to check on my mother.

Illusions were easy at a distance. I was discovering that up close they were harder to sustain. Nina had aged physically, of course, although I suspected the process had been smoothed somewhat by a surgeon’s skill. There were feathery lines in the skin around her dark eyes, a slight sag in the soft skin beneath her jawline. But that seemed to me as inconsequential as it was inevitable. She was still an extraordinarily beautiful woman.

The problem wasn’t with Nina’s beauty; it was with how much of herself she seemed to have invested in her beauty. I couldn’t be with her long without noticing how often her hand smoothed the skin of her neck or how, when she passed a store window, she would seek out her reflection with anxious eyes.

That night at the Mendel as I watched her bending closer to the mirror in her cupped hand, I felt a pang. But Nina had spent a lot of years assuring me that I had value. Now it was my turn. I walked over and sat down beside her. “You’re perfect,” I said, and she was. From the smooth line of her dark hair to her dress ߝ high-necked, longsleeved, meticulously cut from some material that shimmered green and purple and gold in the half light ߝ to her silky stockings and shining kid pumps, Nina Love was as flawless as money and sustained effort could make a woman. She snapped the compact shut and laughed. “Jo, I can always count on you. You’ve always been my biggest fan. That’s why I was so worried when you were late.” Then her face grew serious. “Wasn’t that terrifying out there?”

Our knees were almost touching, but I still had to lean toward Nina to hear her. Sally always said that her mother’s soft, breathy voice was a trick to get everyone to pay attention to nothing but her. Trick or not, as I listened to Nina that winter evening, I felt the sense of homecoming I always felt when I walked through a door and found her waiting.

At that moment, she was looking at me critically. “You seem to be a little the worse for wear.”

“Well, I walked over, and as my grandfather used to say, it’s colder than a witch’s teat out there. Then I had an encounter with someone exercising her democratic right to jab me in the back with her picket sign.”

“Those creatures out there aren’t human,” she said. “It’s been a nightmare for us. Stuart’s phone rings at all hours of the day and night. I’m afraid to take the mail out of the mailbox. Even Taylor is being hurt. Yesterday, a little boy at play school told Taylor her mother should be tied up and thrown in the river.”

“Oh, no, what did Taylor do?”

“She told the boy that at least her mother didn’t have a mustache.”

I could feel the corners of my mouth begin to twitch. “A mustache?”

“According to Taylor, the boy’s mother needs a shave,”

Nina said dryly. “But, Jo, I’m afraid I’m beyond laughing at any of this. I really wonder what can be going through Sally’s mind. First she leaves her husband and child, then she makes a piece of art that outrages everyone and puts Stuart in a terrible position professionally.”

“Nina, I don’t think you’re being fair, at least not about the painting. I don’t know much about these things, but from what I read Sally’s a hot ticket in the art world now. That fresco must be worth a king’s ransom.”

“Oh, you’re right about that, and of course that’s what makes Stuart’s position so difficult. He’s the director, and the director’s duty is to acquire the best. But he also has a board to deal with and a community to appease. Sally could have painted anything else and people would have been all over the place being grateful to her and to Stuart. As they should be. She’s an incredible artist. But she has to have her joke. And so she gives the Mendel a gift that could destroy it. Jo, that fresco of Sally’s is a real Trojan horse.” Nina reached behind her and pulled a faded bloom from an azalea.

“I guess I don’t have much sense of proportion about this. It’s been so terrible for Stuart and, of course, for Taylor.”

“But at least they have you, dear,” I said. “I’m sure Stuart would have broken into a million pieces if you hadn’t been there to make a home for Taylor and for him. You didn’t see him in those first weeks after Sally left. He was like a ghost walker. She was the centre of his life . . .”

Nina’s face was impassive. “She’s always the centre of everybody’s life, isn’t she? Right from the beginning . . .”

But she didn’t finish the sentence. Stuart Lachlan had come into the conservatory.

“Look, there he is at the door. Doesn’t he look fine?” she said.

Stu did, indeed, look fine. As I’d told Nina, his suffering after Sally left had been so intense it seemed to mark him physically. But tonight he looked better ߝ tentative, like a man coming back from a long illness, but immaculate again, as he was in the days when he and Sally were together. He was a handsome man in his late forties, dark-eyed, dark-haired, with the taut body of a swimmer who never misses a day doing laps. He was wearing a dinner jacket and a surprising and beautiful tie and cummerbund of flowered silk. When he leaned over to kiss me, his cheek was smooth, and he smelled of expensive aftershave.

“Merry Christmas, Jo. With everything else that’s been going on, the birthday of the Prince of Peace seems to have been lost in the shuffle. But it’s good to be able to wish you joy in person. Your coming here to teach was the second best thing to happen this year.”

“I don’t have to ask you what the first was. Nina’s obviously taking wonderful care of you. You look great, Stu, truly.”

“Well, the tie and the cummerbund are Nina’s gift. Cosmopolitan and unorthodox, like me, she says.” He laughed, but he looked at me eagerly, waiting for his compliment. I smiled past him at Nina, the shameless flatterer. “She’s right, as usual. Do you have time to sit with us for a minute?” “No, I’m afraid it’s time for me to make my little talk and get this opening underway. I just came in to get Nina.”

Then, flawlessly mannered as always, he offered an arm to each of us. “And of course to escort you, Jo.”

It had been a long time since I’d needed an escort, but when we walked into the foyer, I was glad Stuart was there for Nina. The picketers had come through the door. They couldn’t have been there long because nothing was happening.

They had the punchy look of game show contestants who’ve won the big prize but aren’t sure how to get offstage. The people in evening dress were eying them warily, but everything was calm. Then the tv cameras came inside, and the temperature rose. Someone pushed someone else, and little brush fires of violence seemed to break out all over the room. A woman in an exquisite lace evening gown grabbed a picket sign from a young man and threw it to the floor and stomped on it. The young man bent to pull the sign out from under her and knocked her off balance. When she fell, a man who seemed to be her husband took a swing at the young picketer. Then another man swung at the husband and connected. I heard the unmistakable dull crunch of fist hitting bone, and the husband was down. Then the police were all around and it was over.

From the Paperback edition.

I was fifteen years old, and I had never seen a dead man, but I knew Desmond Love was dead. He was sitting in his place at the dining-room table, but his head lolled back on his neck as if something critical had come loose, and his mouth hung open as if he were sleeping or screaming. His wife, Nina, was in the chair across from him. She was always full of grace, and she had fallen so that her head rested against the curve of her arm as it lay on the table. She was beautiful, but her skin was waxen, and I could hear the rattle of her breathing in that quiet room. My friend Sally was lying on the floor. She had vomited; she was pale and her breathing was laboured, but I knew she wouldn’t die. She was thirteen years old, and you don’t die when you’re thirteen.

It was Nina I went to. My relationship with my own mother had never been easy, and Nina had been my refuge for as long as I could remember. I took her in my arms and began to cry and call her name. Izaak Levin was still standing in the doorway, but seeing me with Nina seemed to jolt him back to reality.

“Joanne, you have to get your father. We need a doctor here,” he said.

My legs felt heavy, the way they do in a dream when you try to run and you can’t, but somehow I got to our cottage and brought my father. He was a methodical and reassuring man, and as I watched him taking pulses, looking into pupils, checking breathing, I felt better.

“What happened?” he asked Izaak Levin.

Izaak shook his head. When he spoke, his voice was dead with disbelief. “I don’t know. I took the boat over to town for a drink before dinner. When I got back, I found them like this.” He pointed to a half-filled martini pitcher on the table. At Sally’s place there was a glass with an inch of soft drink in the bottom. “He must have put it in the drinks. I guess he decided it wasn’t worth going on, and he wanted to take them with him.”

There was no need to explain the pronouns. My father and I knew what he meant. At the beginning of the summer Desmond Love had suffered a stroke that had slurred his speech, paralyzed his right side and, most seriously, stilled his hand. He was forty years old, a bold and innovative maker of art and a handsome and immensely physical man. It was believable that, in his rage at the ravages of the stroke, he would kill himself, and so I stored away Izaak’s explanation.

I stored it away in the same place I stored the other memories of that night: the animal sound of retching Nina made after my father forced the ipecac into her mouth. The silence broken only by a loon’s cry as my father and Izaak carried the Loves, one by one, down to the motorboat at the dock. The blaze of the sunset on the lake as my father wrapped Nina and Sally in the blankets they kept in the boat for picnics. The terrible emptiness in Desmond Love’s eyes as they looked at the September sky.

And then my father, standing in the boat, looking at me on the dock, “Joanne, you’re old enough to know the truth here: Sally will be all right, but Des is dead and I’m not sure about Nina’s chances. It’ll be better for you later if you don’t ride in this boat tonight.” His voice was steady, but there were tears in his eyes. Desmond Love had been his best friend since they were boys. “I want you to go back home and wait for me. Just tell your mother there’s been an emergency. Don’t tell her . . .”

“The truth.” I finished the sentence for him. The truth would make my mother start drinking. So would a lie. It never took much.

“Don’t let Nina die,” I said in an odd, strangled voice.

“I’ll do all I can,” he said, and then the quiet of the night was shattered by the roar of the outboard motor; the air was filled with the smell of gasoline, and the boat, low in the water from its terrible cargo, began to move across the lake into the brilliant gold of the sunset. It was the summer of 1958, and I was alone on the dock, waiting.

* * *

Thirty-two years later I was walking across the bridge that links the university community to the city of Saskatoon. It was the night of the winter solstice. The sky was high and starless, and there was a bone-chilling wind blowing down the South Saskatchewan River from the north. I was on my way to the opening of an exhibition of the work of Sally Love. As soon as I turned onto Spadina Crescent, I could see the bright letters of her name on the silk banners suspended over the entrance to the Mendel Gallery: Sally Love. Sally Love. Sally Love. There was something festive and celebratory about those paint-box colours, but as I got closer I saw there were other signs, too, and some of them weren’t so pretty. These signs were mounted on stakes held by people whose faces shone with zeal, and their crude lettering seemed to pulse with indignation: “Filth Belongs in Toilets Not on Walls,” “Jail Pornographers,” “No Room for Love Here” and one that said simply, “Bitch.”

A crowd had gathered. Some people were attempting a counterattack, and every so often a voice, thin and self-conscious in the winter air, would raise itself in a tentative defence: “What about freedom of the arts?” “We’re not a police state yet!” “The only real obscenity is censorship.”

A tv crew had set up under the lights of the entrance and they were interviewing a soft-looking man in a green tuque with the Hilltops logo and a nylon ski jacket that said “Silver Broom: Saskatoon ’90.” The man was one of our city councillors, and as I walked up I could hear his spiritless baritone spinning out the clichés for the ten o’clock news: “Community standards . . . public property . . . our children’s innocence . . . privacy of the home . . .” The councillor’s name was Hank Mewhort, and years before I had been at a political fundraiser where he had dressed as a leprechaun to deliver the financial appeal. As I walked carefully around the camera crew, Hank’s sanctimonious bleat followed me. I had liked him better as a leprechaun.

When I handed my invitation to a commissionaire posted at the entrance, he checked my name off on a list and opened the gallery door for me. As I started through, I felt a sharp blow in the middle of my back. I turned and found myself facing a fresh-faced woman with a sweet and vacant smile.

She was grasping her sign so the shaft was in front of her like a broadsword. She came at me again, but then, very quickly, a city cop grabbed her from behind and led her off into the night. She was still smiling. Her sign lay on the concrete in front of me, its message carefully spelled out in indelible marker the colour of dried blood: “The Wages of Sin is Death.” I shuddered and pulled my coat tight around me. Inside, all was light and airiness and civility. People dressed in holiday evening clothes greeted one another in the reverent tones Canadians use at cultural events. A Douglas fir, its boughs luminous with yellow silk bows, filled the air with the smell of Christmas. In front of the tree was an easel with a handsome poster announcing the Sally Love exhibition. Propped discreetly against it was a small placard stating that Erotobiography was in Gallery III at the rear of the building and that patrons must be eighteen years of age to be admitted.

Very prim. Very innocent. But this small addendum to Sally’s show had eclipsed everything else. To the left of the Douglas fir, a wall plastered with newspaper clippings told the story: Erotobiography consisted of seven pictures Sally Love had painted to record her sexual experiences.

All the pictures were explicit, but the one that had caused the furor was a fresco. A fresco, the local paper noted sternly, is permanent. The colour in a fresco does not rest on the surface; it sinks into and becomes part of the wall. And what Sally Love had chosen to sink into the wall of the publicly owned Mendel Gallery was a painting of the sexual parts of all the people with whom she had been intimate. Erotobio - graphy. According to the newspaper, there were one hundred individual entries, and a handful of the genitalia were female. Nonetheless, community standards being what they are, the work was known by everyone as the Penis Painting.

The exhibition that was opening that night was a large one. Several of the pictures on loan from major galleries throughout North America had been heralded as altering the direction of contemporary art; many of the paintings had been praised for their psychological insights or their technical virtuosity. None of that seemed to matter much.

It was the penises that had prompted the people outside to leave their warm living rooms and clutch the shafts of picket signs in their mittened hands. It was the penises the handsome men and women exchanging soft words in the foyer had come to see. As I walked toward the wing where Nina Love and I had agreed to meet, I was smiling. I had to admit that I wanted to see the penises, too. The rest was just foreplay.

The south wing of the Mendel Gallery is a conservatory, a place where you can find green and flowering things even when the temperature sticks at forty below for weeks on end. When I stepped through the door, the moisture and the warmth and the fragrance enveloped me, and for a moment I stood there and let the cold and the tension flow out of my body. Nina Love was sitting on a bench in front of a blazing display of amaryllis, azalea and bird of paradise. She had a compact cupped in her hand, and her attention was wholly focused on her reflection. It was, I thought sadly, becoming her characteristic gesture.

That night as I was getting ready for Sally’s opening, I’d heard the actress Diane Keaton answer a radio interviewer’s question about how she faced aging. “You have to be very brave,” she’d said, and I’d thought of Nina. Much as I cared for her I had to admit that Nina Love wasn’t being very brave about growing older.

Until Thanksgiving, when she had come to Saskatoon to help care for her granddaughter, Nina and I had kept in touch mostly through letters and phone calls. I’d seen her only on those rare occasions when I was in Toronto to check on my mother.

Illusions were easy at a distance. I was discovering that up close they were harder to sustain. Nina had aged physically, of course, although I suspected the process had been smoothed somewhat by a surgeon’s skill. There were feathery lines in the skin around her dark eyes, a slight sag in the soft skin beneath her jawline. But that seemed to me as inconsequential as it was inevitable. She was still an extraordinarily beautiful woman.

The problem wasn’t with Nina’s beauty; it was with how much of herself she seemed to have invested in her beauty. I couldn’t be with her long without noticing how often her hand smoothed the skin of her neck or how, when she passed a store window, she would seek out her reflection with anxious eyes.

That night at the Mendel as I watched her bending closer to the mirror in her cupped hand, I felt a pang. But Nina had spent a lot of years assuring me that I had value. Now it was my turn. I walked over and sat down beside her. “You’re perfect,” I said, and she was. From the smooth line of her dark hair to her dress ߝ high-necked, longsleeved, meticulously cut from some material that shimmered green and purple and gold in the half light ߝ to her silky stockings and shining kid pumps, Nina Love was as flawless as money and sustained effort could make a woman. She snapped the compact shut and laughed. “Jo, I can always count on you. You’ve always been my biggest fan. That’s why I was so worried when you were late.” Then her face grew serious. “Wasn’t that terrifying out there?”

Our knees were almost touching, but I still had to lean toward Nina to hear her. Sally always said that her mother’s soft, breathy voice was a trick to get everyone to pay attention to nothing but her. Trick or not, as I listened to Nina that winter evening, I felt the sense of homecoming I always felt when I walked through a door and found her waiting.

At that moment, she was looking at me critically. “You seem to be a little the worse for wear.”

“Well, I walked over, and as my grandfather used to say, it’s colder than a witch’s teat out there. Then I had an encounter with someone exercising her democratic right to jab me in the back with her picket sign.”

“Those creatures out there aren’t human,” she said. “It’s been a nightmare for us. Stuart’s phone rings at all hours of the day and night. I’m afraid to take the mail out of the mailbox. Even Taylor is being hurt. Yesterday, a little boy at play school told Taylor her mother should be tied up and thrown in the river.”

“Oh, no, what did Taylor do?”

“She told the boy that at least her mother didn’t have a mustache.”

I could feel the corners of my mouth begin to twitch. “A mustache?”

“According to Taylor, the boy’s mother needs a shave,”

Nina said dryly. “But, Jo, I’m afraid I’m beyond laughing at any of this. I really wonder what can be going through Sally’s mind. First she leaves her husband and child, then she makes a piece of art that outrages everyone and puts Stuart in a terrible position professionally.”

“Nina, I don’t think you’re being fair, at least not about the painting. I don’t know much about these things, but from what I read Sally’s a hot ticket in the art world now. That fresco must be worth a king’s ransom.”

“Oh, you’re right about that, and of course that’s what makes Stuart’s position so difficult. He’s the director, and the director’s duty is to acquire the best. But he also has a board to deal with and a community to appease. Sally could have painted anything else and people would have been all over the place being grateful to her and to Stuart. As they should be. She’s an incredible artist. But she has to have her joke. And so she gives the Mendel a gift that could destroy it. Jo, that fresco of Sally’s is a real Trojan horse.” Nina reached behind her and pulled a faded bloom from an azalea.

“I guess I don’t have much sense of proportion about this. It’s been so terrible for Stuart and, of course, for Taylor.”

“But at least they have you, dear,” I said. “I’m sure Stuart would have broken into a million pieces if you hadn’t been there to make a home for Taylor and for him. You didn’t see him in those first weeks after Sally left. He was like a ghost walker. She was the centre of his life . . .”

Nina’s face was impassive. “She’s always the centre of everybody’s life, isn’t she? Right from the beginning . . .”

But she didn’t finish the sentence. Stuart Lachlan had come into the conservatory.

“Look, there he is at the door. Doesn’t he look fine?” she said.

Stu did, indeed, look fine. As I’d told Nina, his suffering after Sally left had been so intense it seemed to mark him physically. But tonight he looked better ߝ tentative, like a man coming back from a long illness, but immaculate again, as he was in the days when he and Sally were together. He was a handsome man in his late forties, dark-eyed, dark-haired, with the taut body of a swimmer who never misses a day doing laps. He was wearing a dinner jacket and a surprising and beautiful tie and cummerbund of flowered silk. When he leaned over to kiss me, his cheek was smooth, and he smelled of expensive aftershave.

“Merry Christmas, Jo. With everything else that’s been going on, the birthday of the Prince of Peace seems to have been lost in the shuffle. But it’s good to be able to wish you joy in person. Your coming here to teach was the second best thing to happen this year.”

“I don’t have to ask you what the first was. Nina’s obviously taking wonderful care of you. You look great, Stu, truly.”

“Well, the tie and the cummerbund are Nina’s gift. Cosmopolitan and unorthodox, like me, she says.” He laughed, but he looked at me eagerly, waiting for his compliment. I smiled past him at Nina, the shameless flatterer. “She’s right, as usual. Do you have time to sit with us for a minute?” “No, I’m afraid it’s time for me to make my little talk and get this opening underway. I just came in to get Nina.”

Then, flawlessly mannered as always, he offered an arm to each of us. “And of course to escort you, Jo.”

It had been a long time since I’d needed an escort, but when we walked into the foyer, I was glad Stuart was there for Nina. The picketers had come through the door. They couldn’t have been there long because nothing was happening.

They had the punchy look of game show contestants who’ve won the big prize but aren’t sure how to get offstage. The people in evening dress were eying them warily, but everything was calm. Then the tv cameras came inside, and the temperature rose. Someone pushed someone else, and little brush fires of violence seemed to break out all over the room. A woman in an exquisite lace evening gown grabbed a picket sign from a young man and threw it to the floor and stomped on it. The young man bent to pull the sign out from under her and knocked her off balance. When she fell, a man who seemed to be her husband took a swing at the young picketer. Then another man swung at the husband and connected. I heard the unmistakable dull crunch of fist hitting bone, and the husband was down. Then the police were all around and it was over.

From the Paperback edition.

Recenzii

"A tense, masterfully written character study; then the killing begins. . . . Bold and powerful."

— Publishers Weekly

"Virtually everything about Murder at the Mendel is first rate."

— London Free Press

"A highly literate mystery. . . . The brew of sex and art is intriguing."

— Whig-Standard (Kingston)

"A splendid novel."

— Times Colonist (Victoria)

"Exciting. . . . The art is described with delicious humour and all the characters are vivid."

— Quill & Quire

"Classic . . . with enough twists to qualify as a page turner. . . . Bowen and her genteel sleuth are here to stay."

— StarPhoenix (Saskatoon)

— Publishers Weekly

"Virtually everything about Murder at the Mendel is first rate."

— London Free Press

"A highly literate mystery. . . . The brew of sex and art is intriguing."

— Whig-Standard (Kingston)

"A splendid novel."

— Times Colonist (Victoria)

"Exciting. . . . The art is described with delicious humour and all the characters are vivid."

— Quill & Quire

"Classic . . . with enough twists to qualify as a page turner. . . . Bowen and her genteel sleuth are here to stay."

— StarPhoenix (Saskatoon)