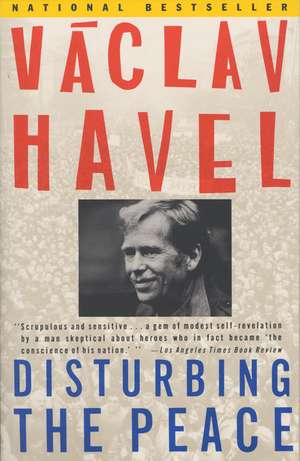

Disturbing the Peace: A Conversation with Karel Huizdala

Autor Vaclav Havelen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 1991

Preț: 84.76 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 127

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.22€ • 16.93$ • 13.42£

16.22€ • 16.93$ • 13.42£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780679734024

ISBN-10: 0679734023

Pagini: 256

Dimensiuni: 132 x 204 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Ediția:Vintage Books.

Editura: VINTAGE BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0679734023

Pagini: 256

Dimensiuni: 132 x 204 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Ediția:Vintage Books.

Editura: VINTAGE BOOKS

Extras

Preface

by Paul Wilson

The history of this book has been marked by history itself.

When Karel Hvížďala first proposed the idea of a book-length interview to Václav Havel in 1985, Hvížďala was living in West Germany, Havel in Prague, and neither of them could visit the other. Havel liked the idea because it would give him a chance to reflect on his life as he approached fifty; he accepted. They worked on the book over the next year, communicating by underground mail. According to Hvížďala, the first approach, in which Havel sent written response to the questions, did not satisfy either of them: the answers were too much like essays. So Hvížďala sent Havel a batch of about fifty questions, and between Christmas and the New Year, Havel shut himself in a borrowed flat and came out with eleven hours of recorded answers. Hvížďala transcribed and edited them, then sent the amnuscript back to Havel with some supplementary questions ("for drama," Hvížďala says). Havel prepared a final version with some new material in it, completing it in early June, 1986.

The book was first published in Prague that same summer under Havel's own samizdat imprint, Edice Expedice. In autumn, a Czech emigré publishing venture in England, Rozmluvy, brought it out in the West. In December 1989—with Czechoslovakia's democratic revolution barely a few weeks old—the Melantrich Press in Prague had it published in seven days. It was the first samizdat book to come out legally in the new Czechoslovakia.

Translating this book was one of the most enjoyable tasks I've ever undertaken. Havel had said it would be "recreation" after the hard labor of Letters to Olga, and he was right. I followed his method of composition, translating it first into a tape recorder, and then editing the transcript. I'm not sure it was any faster that way, but I hope the result has something of the quality of Havel's conversation in it.

The Czech title of this book is Dálkový výslech, which means Long-Distance Interrogation. For a long time, this title stood over my translation too; it was awkward but accurate, and something of the irony of the original does seep through. Then somewhere in the higher councils of publishing, doubts were cast upon the title, and the search for a new one began.

My mind acknowledged the need for a different title, but it refused to work on the problem. Then one day Bobbie Bristol phoned from Knopf and said, "How do you feel about disturbing the peace?" I thought she was suggesting another late-night turn through the Lower East Side (such as we'd had on my last New York trip) ending up in Dan Lynch's bar on Second Avenue. No, she was suggesting a title. It was an intriguing idea: "disturbing the peace" was how I once translated the expression výtržnctví, a crime normally rendered as "hooliganism," for which my friend Ivan Jirous (and many others too) had been sent to prison. Jirous later wrote that he liked my translation because it described exactly what he had done: disturbed the artificial "peace" of the totalitarian system. Although Havel was once charged withvýtržnctví,he was never successfully prosecuted for it; nevertheless disturbing the peace was, in a sense, what he had been doing all along: disturbing the emperor's peace of mind. So the title—not without some debate—was chosen and ultimately cleared with Havel.

There may be purists who object to such negotiations, but it doesn't hurt to remind ourselves that a book, and especially a translation, is a collective creation. I would like to thank everyone who, knowingly or unknowingly, helped in the completion of this work. I am grateful to Ivan and Dáša Havel, and Olga Havlová for many kindnesses; to Vladimír Hanzel for giving me tie when there was none to give; and to the author himself for patiently dealing with my queries in the middle of a revolution. On this end, my thanks go especially to Marcy Laufer, for her prompt and reliable transcripts; to Bobbie Bristol, for far more than the title; to Edwin C. Cohen, for expressing his admiration of Václav Havel in the most direct way possible: by contributing to the translation fee; and to my wife Helena, for putting up with me while I finished work under the pressure of history. As it turned out, it was a history which this book, in part, helped to unleash.

Introduction

by Paul Wilson

Toronto, March 1990

In the spring of 1975, outside the Slavia Café, just across the street from the National Theatre in Prague, a friend handed me a well-thumbed sheaf of typewritten pages and told me to pass it on when I was through. In the real-life paranoia of Czechoslovakia in the 1970s, our encounter had a touch of conspiracy about it: reading or possessing samizdat—self-published works—was not illegal in itself, but circulating it was, and the two of us had just committed a crime. Our chances of being caught were slim, but still real enough to induce a sense of caution in us and add some salt and pepper to the moment. That evening, at home, I sat down to read in a state of excitement that only the knowledge of doing something illicit can bring.

It was an extraordinary essay, addressed to the Czechoslovak president, Gustav Husák, about the desolate state of the country seven years after the Warsaw Pact armies had crushed the Prague Spring. The author described a society governed by fear—not the cold pit-of-the-stomach terror that Stalin had once spread throughout his empire, but a dull, existential fear that seeped into every crack and crevice of daily life and made one think twice about everything one said and did. This fear was maintained by the Secret Police, "that hideous spider whose invisible web runs right through society," and it reduced human action—and therefore history itself—to false pretense.

The letter was, in fact, a state of the union message, and it contained an unforgettable metaphor: the regime, the author said, was "entropic," a force that was gradually reducing the vital energy, diversity, and unpredictability of Czechoslovak society to a state of dull, inert uniformity. And the letter also contained a remarkable prediction: that sooner or later, this regime would become the victim of its own "lethal principle." "Life cannot be destroyed for good," the author wrote. "A secret streamlet trickles on beneath the heavy crust of inertia and pseudo-events, slowly and inconspicuously undermining it. It may be a long process, but one day it has to happen: the crust can no longer hold and starts to crack. This is the moment when something once more begins visibly to happen, something new and unique. . . . History again demands to be heard."

The letter, dated April 8, 1975, was signed "Václav Havel, Writer."

Havel finished this autobiographical interview with Karel Hvížďala in 1986. As I read it again, in the spring of 1990, I am struck by how the extraordinary events of the last few months—events that have toppled communist regimes from Berlin to Bucharest and that have borne the playwright Václav Havel from the ghetto of dissent to the world stage—have enriched it with new levels of meaning. Havel, for instance, describes in detail the struggle, in the mid-sixties, to keep a small literary magazine, Tvár, alive in the face of pressure from the Communist Party to close it down. In this struggle, Havel discovered what he called "a new model of behavior": when arguing with a center of power, don't get sidetracked into vague ideological debates about who is right or wrong; fight for specific, concrete things, and be prepared to stick to your guns to the end.

On Tuesday morning, November 28, 1989, Havel led a delegation of the Civic Forum to negotiate with the Communist-dominated government. The issue was not a magazine this time, it was the country. Ten days before that, the "velvet revolution" had been set in motion by a student demonstration in Prague; that was followed by a week of massive demonstrations culminating in a general strike on Monday, November 27. Early Tuesday afternoon, following the meeting, the government announced that it had agreed to write the leading role of the Communist Party out of the constitution. We do not know what was said at the meeting, but I don't think we would be far wrong to assume that the discussion stayed very close to the concrete issue of amending the constitution, and that the Civic Forum delegation stuck to their guns. A principle that Havel and his colleagues had learned decades before now stood them in good stead.

The parallels run deeper still. Havel's description of the birth of Charter 77 in 1977 is an almost canny prefiguration of the creation–in radically different circumstances—of the Civic Forum itself. Although for legal reasons it was described as an "initiative" and avoided making overt political proposals, Charter 77 was in fact a political movement in the deepest sense, a coalition of many groups of people from widely different backgrounds, ranging from former party members who still thought of themselves as Marxists to noncommunists who had never had anything to do with the party (except perhaps as its victims), but who all agreed on the fundamental importance of openness, tolerance, and respect for human rights. Havel describes the plurality of the Charter as something historically new for Czechoslovakia, something that would germinate a genuine social tolerance. Regardless of how it turned out, this achievement could not be wiped out of the national memory. "It was a steeping out toward life," he says, "toward a genuine state of thinking about common matters . . . and the cost of doing so was saying goodbye forever to the principle of 'the leading role of the party."

In one sense, the Civic Forum, the creation of which Havel announced on November 19th in the Činoherní Klub in Prague, was Charter 77 writ large. Like the Charter, it was a coalition of all the forces in society (and by 1989 there were many) that had sought nonviolent, nonpartisan solution to the crisis. The Civic Forum's program, called "What We Want" and issued only a week later, was drafted by, among others, Charter signatories; it strongly reflected the discussions that Charter 77 and other civic groups had been carrying on among themselves for the previous thirteen years. Moreover, the Forum's miraculous ability to act quickly, to make rapid decisions, to organize efficiently (despite appearing utterly chaotic), and to communicate effectively was possible largely thanks to the wide network built up over the years in difficult conditions among dissident and quasi-dissident groups. The atmosphere of those chaotic, exhilarating early days of revolution in November and December (so vividly described by Timothy Garton Ash in The New York Review of Books, and reprinted in his new book, The Magic Lantern) is anticipated in miniature by Havel's account of the early days of Charter 77, when his flat, as he said, "began to look suspiciously the way the New York Stock Exchange must have looked during the crash of '29, or like some center of revolution." There was a big difference, though: in 1977, the "hideous spider" was weaving its web tightly around the Chartists: in 1989, the spider had withdrawn, and the nation was beginning the enormous task of disentangling itself.

Disturbing the Peace, though, offers far more than insights into Havel the President, Havel the first among equals in a democracy struggling courageously to be reborn. It is a detailed and complex self-portrait of a man who sees himself both as an ordinary person, with down-to-earth needs and desires and aspirations and humors (he once said that the reason he was never tempted to emigrate was that he was just a Czech bumpkin at heart and he liked it there) and as someone whose destiny is interwoven with the destiny of his country. Havel, the writer by choice who became a politician malgré lui, has literally written himself into his country's history. His power as a writer and his power as a politician come from the same source: his capacity to voice the hopes and fears of people around him. But he sees his role realistically. "Occasionally," he writes, "I have the desire to cry out: 'I'm tired of playing the builder's role, I just want to do what every writer should do, to tell the truth!' . . . Or: 'Take your own risks; I'm not your savior!' But I always bite my tongue before I speak, and remind myself of what Patočka once told me: the real test of a man is not how well he plays the role he has invented for himself, but how well he plays the role that destiny assigned to him."

by Paul Wilson

The history of this book has been marked by history itself.

When Karel Hvížďala first proposed the idea of a book-length interview to Václav Havel in 1985, Hvížďala was living in West Germany, Havel in Prague, and neither of them could visit the other. Havel liked the idea because it would give him a chance to reflect on his life as he approached fifty; he accepted. They worked on the book over the next year, communicating by underground mail. According to Hvížďala, the first approach, in which Havel sent written response to the questions, did not satisfy either of them: the answers were too much like essays. So Hvížďala sent Havel a batch of about fifty questions, and between Christmas and the New Year, Havel shut himself in a borrowed flat and came out with eleven hours of recorded answers. Hvížďala transcribed and edited them, then sent the amnuscript back to Havel with some supplementary questions ("for drama," Hvížďala says). Havel prepared a final version with some new material in it, completing it in early June, 1986.

The book was first published in Prague that same summer under Havel's own samizdat imprint, Edice Expedice. In autumn, a Czech emigré publishing venture in England, Rozmluvy, brought it out in the West. In December 1989—with Czechoslovakia's democratic revolution barely a few weeks old—the Melantrich Press in Prague had it published in seven days. It was the first samizdat book to come out legally in the new Czechoslovakia.

Translating this book was one of the most enjoyable tasks I've ever undertaken. Havel had said it would be "recreation" after the hard labor of Letters to Olga, and he was right. I followed his method of composition, translating it first into a tape recorder, and then editing the transcript. I'm not sure it was any faster that way, but I hope the result has something of the quality of Havel's conversation in it.

The Czech title of this book is Dálkový výslech, which means Long-Distance Interrogation. For a long time, this title stood over my translation too; it was awkward but accurate, and something of the irony of the original does seep through. Then somewhere in the higher councils of publishing, doubts were cast upon the title, and the search for a new one began.

My mind acknowledged the need for a different title, but it refused to work on the problem. Then one day Bobbie Bristol phoned from Knopf and said, "How do you feel about disturbing the peace?" I thought she was suggesting another late-night turn through the Lower East Side (such as we'd had on my last New York trip) ending up in Dan Lynch's bar on Second Avenue. No, she was suggesting a title. It was an intriguing idea: "disturbing the peace" was how I once translated the expression výtržnctví, a crime normally rendered as "hooliganism," for which my friend Ivan Jirous (and many others too) had been sent to prison. Jirous later wrote that he liked my translation because it described exactly what he had done: disturbed the artificial "peace" of the totalitarian system. Although Havel was once charged withvýtržnctví,he was never successfully prosecuted for it; nevertheless disturbing the peace was, in a sense, what he had been doing all along: disturbing the emperor's peace of mind. So the title—not without some debate—was chosen and ultimately cleared with Havel.

There may be purists who object to such negotiations, but it doesn't hurt to remind ourselves that a book, and especially a translation, is a collective creation. I would like to thank everyone who, knowingly or unknowingly, helped in the completion of this work. I am grateful to Ivan and Dáša Havel, and Olga Havlová for many kindnesses; to Vladimír Hanzel for giving me tie when there was none to give; and to the author himself for patiently dealing with my queries in the middle of a revolution. On this end, my thanks go especially to Marcy Laufer, for her prompt and reliable transcripts; to Bobbie Bristol, for far more than the title; to Edwin C. Cohen, for expressing his admiration of Václav Havel in the most direct way possible: by contributing to the translation fee; and to my wife Helena, for putting up with me while I finished work under the pressure of history. As it turned out, it was a history which this book, in part, helped to unleash.

Introduction

by Paul Wilson

Toronto, March 1990

In the spring of 1975, outside the Slavia Café, just across the street from the National Theatre in Prague, a friend handed me a well-thumbed sheaf of typewritten pages and told me to pass it on when I was through. In the real-life paranoia of Czechoslovakia in the 1970s, our encounter had a touch of conspiracy about it: reading or possessing samizdat—self-published works—was not illegal in itself, but circulating it was, and the two of us had just committed a crime. Our chances of being caught were slim, but still real enough to induce a sense of caution in us and add some salt and pepper to the moment. That evening, at home, I sat down to read in a state of excitement that only the knowledge of doing something illicit can bring.

It was an extraordinary essay, addressed to the Czechoslovak president, Gustav Husák, about the desolate state of the country seven years after the Warsaw Pact armies had crushed the Prague Spring. The author described a society governed by fear—not the cold pit-of-the-stomach terror that Stalin had once spread throughout his empire, but a dull, existential fear that seeped into every crack and crevice of daily life and made one think twice about everything one said and did. This fear was maintained by the Secret Police, "that hideous spider whose invisible web runs right through society," and it reduced human action—and therefore history itself—to false pretense.

The letter was, in fact, a state of the union message, and it contained an unforgettable metaphor: the regime, the author said, was "entropic," a force that was gradually reducing the vital energy, diversity, and unpredictability of Czechoslovak society to a state of dull, inert uniformity. And the letter also contained a remarkable prediction: that sooner or later, this regime would become the victim of its own "lethal principle." "Life cannot be destroyed for good," the author wrote. "A secret streamlet trickles on beneath the heavy crust of inertia and pseudo-events, slowly and inconspicuously undermining it. It may be a long process, but one day it has to happen: the crust can no longer hold and starts to crack. This is the moment when something once more begins visibly to happen, something new and unique. . . . History again demands to be heard."

The letter, dated April 8, 1975, was signed "Václav Havel, Writer."

Havel finished this autobiographical interview with Karel Hvížďala in 1986. As I read it again, in the spring of 1990, I am struck by how the extraordinary events of the last few months—events that have toppled communist regimes from Berlin to Bucharest and that have borne the playwright Václav Havel from the ghetto of dissent to the world stage—have enriched it with new levels of meaning. Havel, for instance, describes in detail the struggle, in the mid-sixties, to keep a small literary magazine, Tvár, alive in the face of pressure from the Communist Party to close it down. In this struggle, Havel discovered what he called "a new model of behavior": when arguing with a center of power, don't get sidetracked into vague ideological debates about who is right or wrong; fight for specific, concrete things, and be prepared to stick to your guns to the end.

On Tuesday morning, November 28, 1989, Havel led a delegation of the Civic Forum to negotiate with the Communist-dominated government. The issue was not a magazine this time, it was the country. Ten days before that, the "velvet revolution" had been set in motion by a student demonstration in Prague; that was followed by a week of massive demonstrations culminating in a general strike on Monday, November 27. Early Tuesday afternoon, following the meeting, the government announced that it had agreed to write the leading role of the Communist Party out of the constitution. We do not know what was said at the meeting, but I don't think we would be far wrong to assume that the discussion stayed very close to the concrete issue of amending the constitution, and that the Civic Forum delegation stuck to their guns. A principle that Havel and his colleagues had learned decades before now stood them in good stead.

The parallels run deeper still. Havel's description of the birth of Charter 77 in 1977 is an almost canny prefiguration of the creation–in radically different circumstances—of the Civic Forum itself. Although for legal reasons it was described as an "initiative" and avoided making overt political proposals, Charter 77 was in fact a political movement in the deepest sense, a coalition of many groups of people from widely different backgrounds, ranging from former party members who still thought of themselves as Marxists to noncommunists who had never had anything to do with the party (except perhaps as its victims), but who all agreed on the fundamental importance of openness, tolerance, and respect for human rights. Havel describes the plurality of the Charter as something historically new for Czechoslovakia, something that would germinate a genuine social tolerance. Regardless of how it turned out, this achievement could not be wiped out of the national memory. "It was a steeping out toward life," he says, "toward a genuine state of thinking about common matters . . . and the cost of doing so was saying goodbye forever to the principle of 'the leading role of the party."

In one sense, the Civic Forum, the creation of which Havel announced on November 19th in the Činoherní Klub in Prague, was Charter 77 writ large. Like the Charter, it was a coalition of all the forces in society (and by 1989 there were many) that had sought nonviolent, nonpartisan solution to the crisis. The Civic Forum's program, called "What We Want" and issued only a week later, was drafted by, among others, Charter signatories; it strongly reflected the discussions that Charter 77 and other civic groups had been carrying on among themselves for the previous thirteen years. Moreover, the Forum's miraculous ability to act quickly, to make rapid decisions, to organize efficiently (despite appearing utterly chaotic), and to communicate effectively was possible largely thanks to the wide network built up over the years in difficult conditions among dissident and quasi-dissident groups. The atmosphere of those chaotic, exhilarating early days of revolution in November and December (so vividly described by Timothy Garton Ash in The New York Review of Books, and reprinted in his new book, The Magic Lantern) is anticipated in miniature by Havel's account of the early days of Charter 77, when his flat, as he said, "began to look suspiciously the way the New York Stock Exchange must have looked during the crash of '29, or like some center of revolution." There was a big difference, though: in 1977, the "hideous spider" was weaving its web tightly around the Chartists: in 1989, the spider had withdrawn, and the nation was beginning the enormous task of disentangling itself.

Disturbing the Peace, though, offers far more than insights into Havel the President, Havel the first among equals in a democracy struggling courageously to be reborn. It is a detailed and complex self-portrait of a man who sees himself both as an ordinary person, with down-to-earth needs and desires and aspirations and humors (he once said that the reason he was never tempted to emigrate was that he was just a Czech bumpkin at heart and he liked it there) and as someone whose destiny is interwoven with the destiny of his country. Havel, the writer by choice who became a politician malgré lui, has literally written himself into his country's history. His power as a writer and his power as a politician come from the same source: his capacity to voice the hopes and fears of people around him. But he sees his role realistically. "Occasionally," he writes, "I have the desire to cry out: 'I'm tired of playing the builder's role, I just want to do what every writer should do, to tell the truth!' . . . Or: 'Take your own risks; I'm not your savior!' But I always bite my tongue before I speak, and remind myself of what Patočka once told me: the real test of a man is not how well he plays the role he has invented for himself, but how well he plays the role that destiny assigned to him."

Descriere

Although in many ways this book stands as an informal autobiography of the playwright turned statesman, these eloquent and often witty interviews do much more than just recapitulate how Vaclav Havel helped transform Czechoslovakia into a democracy. Havel gives insights into Czech history, the social and political roles of art, and a statement of the values underlying recent events in Eastern Europe. A national bestseller.

Notă biografică

Václav Havel was born in Czechoslovakia in 1936. Among his plays, those best known in the West areThe Garden Party,The Memorandum,Largo Desolato, Temptation, and three one-act plays,Audience,Private View, andProtest. He is a founding spokesman of Charter 77 and the author of many influential essays on the nature of totalitarianism and dissent. In 1979 he was sentenced to four and a half years in prison for his involvement in the human rights movement. Out of this imprisonment came his book of letters to his wife,Letters to Olga(1981). In 1989 he helped to found the Civic Forum, the first legal opposition movement in Czechoslovakia in 40 years; in December 1989 he was elected president of Czechoslovakia; and in 1994 became the first president of the independent Czech Republic. His memoir,To the Castle and Back, was published in 2007. He died in 2011 at the age of 75.