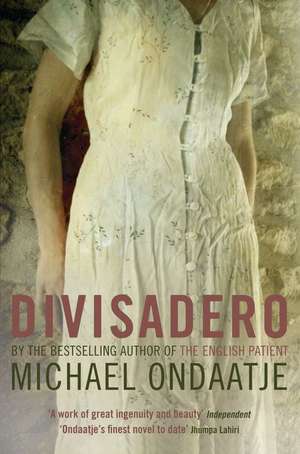

Divisadero

Autor Michael Ondaatjeen Limba Engleză Paperback – 3 aug 2008

It is the 1970s in Northern California. A farmer and his teenage daughters, Anna and Claire, work the land with the help of Coop, the enigmatic young man who lives with them. Theirs is a makeshift family, until they are riven by an incident of violence - of both hand and heart - that 'sets fire to the rest of their lives'. This is a story of possession and loss, about the often discordant demands of family, love, and memory. Written in the sensuous prose for which Michael Ondaatje's fiction is celebrated, Divisadero is the work of a master story-teller.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 62.09 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| Bloomsbury Publishing – 3 aug 2008 | 62.09 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| Vintage Books USA – 31 mar 2008 | 120.26 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 62.09 lei

Preț vechi: 82.09 lei

-24% Nou

Puncte Express: 93

Preț estimativ în valută:

11.88€ • 12.17$ • 9.88£

11.88€ • 12.17$ • 9.88£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 26 februarie-12 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780747592686

ISBN-10: 0747592683

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 129 x 198 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: Bloomsbury Publishing

Colecția Bloomsbury Paperbacks

Locul publicării:London, United Kingdom

ISBN-10: 0747592683

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 129 x 198 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: Bloomsbury Publishing

Colecția Bloomsbury Paperbacks

Locul publicării:London, United Kingdom

Caracteristici

The long-awaited fifth novel from Michael Ondaatje: a sweeping, elegaic story on the scale of The English Patient

SHORTLISTED FOR THE GILLER PRIZE, THE 2008 COMMONWEALTH WRITERS' PRIZE &WINNER OF THE GOVERNOR GENERAL'S LITERARY AWARD FOR FICTION 2007

SHORTLISTED FOR THE GILLER PRIZE, THE 2008 COMMONWEALTH WRITERS' PRIZE &WINNER OF THE GOVERNOR GENERAL'S LITERARY AWARD FOR FICTION 2007

Notă biografică

Michael Ondaatje is the author of four previous novels, a memoir, a non-fiction book on film and several books of poetry. His novel The English Patient won the Booker Prize; another of his novels, Anil's Ghost, won the Irish Times International Fiction Prize and the Prix Medicis. Born in Sri Lanka, he now lives in Toronto.

Recenzii

'Hauntingly beautiful ... What an unusual, and unusually rich, experience it is to read Divisadero ... those who spend time within its pages will discover even more proof - not that they needed it - of Michael Ondaatje's peerlessness as a storyteller and poet'

'Magnificent ... From its first to last telling sentence, this aesthetic tale, poetic with human detail, is a rare and precious pleasure'

'Plumply imagined, deeply romantic but vividly traumatic ... This novel bravely jostles the uncomfortable edges of literary storytelling'

'My life always stops for a new book by Michael Ondaatje. I began Divisadero as soon as it came into my possession and over the course of a few evenings was captivated by Ondaatje's finest novel to date'

'Magnificent ... From its first to last telling sentence, this aesthetic tale, poetic with human detail, is a rare and precious pleasure'

'Plumply imagined, deeply romantic but vividly traumatic ... This novel bravely jostles the uncomfortable edges of literary storytelling'

'My life always stops for a new book by Michael Ondaatje. I began Divisadero as soon as it came into my possession and over the course of a few evenings was captivated by Ondaatje's finest novel to date'

Descriere

The eagerly awaited novel by the internationally acclaimed author of The English Patient and Anil's Ghost

Extras

From Divisadero

By our grandfather’s cabin, on the high ridge, opposite a slope of buckeye trees, Claire sits on her horse, wrapped in a thick blanket. She has camped all night and lit a fire in the hearth of that small structure our ancestor built more than a generation ago, and which he lived in like a hermit or some creature, when he first came to this country. He was a self-sufficient bachelor who eventually owned all the land he looked down onto. He married lackadaisically when he was forty, had one son, and left him this farm along the Petaluma road.

Claire moves slowly on the ridge above the two valleys full of morning mist. The coast is to her left. On her right is the journey to Sacramento and the delta towns such as Rio Vista with its populations left over from the Gold Rush.

She persuades the horse down through the whiteness alongside crowded trees. She has been smelling smoke for the last twenty minutes, and, on the outskirts of Glen Ellen, she sees the town bar on fire —the local arsonist has struck early, when certain it would be empty. She watches from a distance without dismounting. The horse, Territorial, seldom allows a remount; in this he can be fooled only once a day. The two of them, rider and animal, don’t fully trust each other, although the horse is my sister Claire’s closest ally. She will use every trick not in the book to stop his rearing and bucking. She carries plastic bags of water with her and leans forward and smashes them onto his neck so the animal believes it is his own blood and will calm for a minute. When Claire is on a horse she loses her limp and is in charge of the universe, a centaur. Someday she will meet and marry a centaur.

The fire takes an hour to burn down. The Glen Ellen Bar has always been the location of fights, and even now she can see scuffles starting up on the streets, perhaps to honour the landmark. She sidles the animal against the slippery red wood of a madrone bush and eats its berries, then rides down into the town, past the fire. Close by, as she passes, she can hear the last beams collapsing like a roll of thunder, and she steers the horse away from the sound.

On the way home she passes vineyards with their prehistoric-looking heat blowers that keep air moving so the vines don’t freeze. Ten years earlier, in her youth, smudge pots burned all night to keep the air warm.

Most mornings we used to come into the dark kitchen and silently cut thick slices of cheese for ourselves. My father drinks a cup of red wine. Then we walk to the barn. Coop is already there, raking the soiled straw, and soon we are milking the cows, our heads resting against their flanks. A father, his two eleven-year-old daughters, and Coop the hired hand, a few years older than us. No one has talked yet, there’s just been the noise of pails or gates swinging open.

Coop in those days spoke sparingly, in a low-pitched monologue to himself, as if language was uncertain. Essentially he was clarifying what he saw—the light in the barn, where to climb the approaching fence, which chicken to cordon off, capture, and tuck under his arm. Claire and I listened whenever we could. Coop was an open soul in those days. We realized his taciturn manner was not a wish for separateness but a tentativeness about words. He was adept in the physical world where he protected us. But in the world of language he was our student.

At that time, as sisters, we were mostly on our own. Our father had brought us up single-handed and was too busy to be conscious of intricacies. He was satisfied when we worked at our chores and easily belligerent when it became difficult to find us. Since the death of our mother it was Coop who listened to us complain and worry, and he allowed us the stage when he thought we wished for it. Our father gazed right through Coop. He was training him as a farmer and nothing else. What Coop read, however, were books about gold camps and gold mines in the California northeast, about those who had risked everything at a river bend on a left turn and so discovered a fortune. By the second half of the twentieth century he was, of course, a hundred years too late, but he knew there were still outcrops of gold, in rivers, under the bunch grass, or in the pine sierras.

*

Now and then our father embraced us as any father would. This happened only if you were able to catch him in that no-man’s-land between tiredness and sleep, when he seemed wayward to himself. I joined him on the old covered sofa, and I would lie like a slim dog in his arms, imitating his state of weariness—too much sun perhaps, or too hard a day’s work.

Claire would also be there sometimes, if she did not want to be left out, or if there was a storm. But I simply wished to have my face against his checkered shirt and pretend to be asleep. As if inhaling the flesh of an adult was a sin and also a glory, a right in any case. To do such a thing during daylight would have been unthinkable, he’d have pushed us aside. He was not a modern parent, he had been raised with a few male rules, and he no longer had a wife to qualify or compromise his beliefs. So you had to catch him in that twilight state, when he had ceded control on the tartan sofa, his girls enclosed, one in each of his arms. I would watch the flicker under his eyelid, the tremble within that covering skin that signalled his tiredness, as if he were being tugged in mid-river by a rope to some other place. And then I too would sleep, descending into the layer that was closest to him. A father who allows you that should protect you all of your days, I think.

From the Hardcover edition.

By our grandfather’s cabin, on the high ridge, opposite a slope of buckeye trees, Claire sits on her horse, wrapped in a thick blanket. She has camped all night and lit a fire in the hearth of that small structure our ancestor built more than a generation ago, and which he lived in like a hermit or some creature, when he first came to this country. He was a self-sufficient bachelor who eventually owned all the land he looked down onto. He married lackadaisically when he was forty, had one son, and left him this farm along the Petaluma road.

Claire moves slowly on the ridge above the two valleys full of morning mist. The coast is to her left. On her right is the journey to Sacramento and the delta towns such as Rio Vista with its populations left over from the Gold Rush.

She persuades the horse down through the whiteness alongside crowded trees. She has been smelling smoke for the last twenty minutes, and, on the outskirts of Glen Ellen, she sees the town bar on fire —the local arsonist has struck early, when certain it would be empty. She watches from a distance without dismounting. The horse, Territorial, seldom allows a remount; in this he can be fooled only once a day. The two of them, rider and animal, don’t fully trust each other, although the horse is my sister Claire’s closest ally. She will use every trick not in the book to stop his rearing and bucking. She carries plastic bags of water with her and leans forward and smashes them onto his neck so the animal believes it is his own blood and will calm for a minute. When Claire is on a horse she loses her limp and is in charge of the universe, a centaur. Someday she will meet and marry a centaur.

The fire takes an hour to burn down. The Glen Ellen Bar has always been the location of fights, and even now she can see scuffles starting up on the streets, perhaps to honour the landmark. She sidles the animal against the slippery red wood of a madrone bush and eats its berries, then rides down into the town, past the fire. Close by, as she passes, she can hear the last beams collapsing like a roll of thunder, and she steers the horse away from the sound.

On the way home she passes vineyards with their prehistoric-looking heat blowers that keep air moving so the vines don’t freeze. Ten years earlier, in her youth, smudge pots burned all night to keep the air warm.

Most mornings we used to come into the dark kitchen and silently cut thick slices of cheese for ourselves. My father drinks a cup of red wine. Then we walk to the barn. Coop is already there, raking the soiled straw, and soon we are milking the cows, our heads resting against their flanks. A father, his two eleven-year-old daughters, and Coop the hired hand, a few years older than us. No one has talked yet, there’s just been the noise of pails or gates swinging open.

Coop in those days spoke sparingly, in a low-pitched monologue to himself, as if language was uncertain. Essentially he was clarifying what he saw—the light in the barn, where to climb the approaching fence, which chicken to cordon off, capture, and tuck under his arm. Claire and I listened whenever we could. Coop was an open soul in those days. We realized his taciturn manner was not a wish for separateness but a tentativeness about words. He was adept in the physical world where he protected us. But in the world of language he was our student.

At that time, as sisters, we were mostly on our own. Our father had brought us up single-handed and was too busy to be conscious of intricacies. He was satisfied when we worked at our chores and easily belligerent when it became difficult to find us. Since the death of our mother it was Coop who listened to us complain and worry, and he allowed us the stage when he thought we wished for it. Our father gazed right through Coop. He was training him as a farmer and nothing else. What Coop read, however, were books about gold camps and gold mines in the California northeast, about those who had risked everything at a river bend on a left turn and so discovered a fortune. By the second half of the twentieth century he was, of course, a hundred years too late, but he knew there were still outcrops of gold, in rivers, under the bunch grass, or in the pine sierras.

*

Now and then our father embraced us as any father would. This happened only if you were able to catch him in that no-man’s-land between tiredness and sleep, when he seemed wayward to himself. I joined him on the old covered sofa, and I would lie like a slim dog in his arms, imitating his state of weariness—too much sun perhaps, or too hard a day’s work.

Claire would also be there sometimes, if she did not want to be left out, or if there was a storm. But I simply wished to have my face against his checkered shirt and pretend to be asleep. As if inhaling the flesh of an adult was a sin and also a glory, a right in any case. To do such a thing during daylight would have been unthinkable, he’d have pushed us aside. He was not a modern parent, he had been raised with a few male rules, and he no longer had a wife to qualify or compromise his beliefs. So you had to catch him in that twilight state, when he had ceded control on the tartan sofa, his girls enclosed, one in each of his arms. I would watch the flicker under his eyelid, the tremble within that covering skin that signalled his tiredness, as if he were being tugged in mid-river by a rope to some other place. And then I too would sleep, descending into the layer that was closest to him. A father who allows you that should protect you all of your days, I think.

From the Hardcover edition.