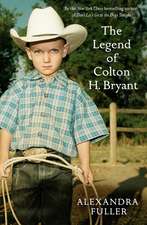

Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight: Picador Classic

Autor Alexandra Fulleren Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2014

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 48.51 lei 3-5 săpt. | +33.10 lei 4-10 zile |

| Pan Macmillan – 31 dec 2014 | 48.51 lei 3-5 săpt. | +33.10 lei 4-10 zile |

| Random House Trade – 28 feb 2003 | 101.90 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Din seria Picador Classic

- 30%

Preț: 49.05 lei

Preț: 49.05 lei - 32%

Preț: 43.47 lei

Preț: 43.47 lei - 32%

Preț: 43.47 lei

Preț: 43.47 lei - 40%

Preț: 43.66 lei

Preț: 43.66 lei - 33%

Preț: 42.29 lei

Preț: 42.29 lei - 46%

Preț: 44.22 lei

Preț: 44.22 lei - 27%

Preț: 48.94 lei

Preț: 48.94 lei - 30%

Preț: 44.67 lei

Preț: 44.67 lei -

Preț: 69.97 lei

Preț: 69.97 lei - 33%

Preț: 46.13 lei

Preț: 46.13 lei - 29%

Preț: 50.87 lei

Preț: 50.87 lei - 30%

Preț: 58.24 lei

Preț: 58.24 lei - 26%

Preț: 49.89 lei

Preț: 49.89 lei - 32%

Preț: 42.93 lei

Preț: 42.93 lei - 32%

Preț: 47.83 lei

Preț: 47.83 lei - 40%

Preț: 43.66 lei

Preț: 43.66 lei - 29%

Preț: 88.77 lei

Preț: 88.77 lei - 31%

Preț: 48.36 lei

Preț: 48.36 lei - 29%

Preț: 46.07 lei

Preț: 46.07 lei - 30%

Preț: 49.52 lei

Preț: 49.52 lei - 33%

Preț: 46.38 lei

Preț: 46.38 lei - 31%

Preț: 43.59 lei

Preț: 43.59 lei - 31%

Preț: 47.91 lei

Preț: 47.91 lei - 37%

Preț: 43.88 lei

Preț: 43.88 lei - 30%

Preț: 45.27 lei

Preț: 45.27 lei -

Preț: 70.42 lei

Preț: 70.42 lei - 22%

Preț: 53.24 lei

Preț: 53.24 lei - 40%

Preț: 44.22 lei

Preț: 44.22 lei - 36%

Preț: 48.78 lei

Preț: 48.78 lei

Preț: 48.51 lei

Preț vechi: 70.23 lei

-31% Nou

Puncte Express: 73

Preț estimativ în valută:

9.29€ • 10.09$ • 7.80£

9.29€ • 10.09$ • 7.80£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-15 aprilie

Livrare express 15-21 martie pentru 43.09 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781447275084

ISBN-10: 144727508X

Pagini: 336

Dimensiuni: 128 x 195 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Ediția:Main Market Ed

Editura: Pan Macmillan

Seria Picador Classic

ISBN-10: 144727508X

Pagini: 336

Dimensiuni: 128 x 195 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Ediția:Main Market Ed

Editura: Pan Macmillan

Seria Picador Classic

Notă biografică

Alexandra Fuller was born in England in 1969. In 1972 she moved with her family to a farm in Rhodesia. After that country’s civil war in 1981, the Fullers moved first to Malawi, then to Zambia. Fuller received a B.A. from Acadia University in Nova Scotia, Canada. In 1994, she moved to Wyoming, where she still lives. She has two children.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter 1

rhodesia, 1976

Mum says, "Don't come creeping into our room at night."

They sleep with loaded guns beside them on the bedside rugs. She

says, "Don't startle us when we're sleeping."

"Why not?"

"We might shoot you."

"Oh."

"By mistake."

"Okay." As it is, there seems a good enough chance of getting shot on

purpose. "Okay, I won't."

So if I wake in the night and need Mum and Dad, I call Vanessa,

because she isn't armed. "Van! Van, hey!" I hiss across the room

until she wakes up. And then Van has to light a candle and escort me

to the loo, where I pee sleepily into the flickering yellow light and

Van keeps the candle high, looking for snakes and scorpions and

baboon spiders.

Mum won't kill snakes because she says they help to keep the rats

down (but she rescued a nest of baby mice from the barns and left

them to grow in my cupboard, where they ate holes in the family's

winter jerseys). Mum won't kill scorpions either; she catches them

and lets them go free in the pool and Vanessa and I have to rake the

pool before we can swim. We fling the scorps as far as we can across

the brown and withering lawn, chase the ducks and geese out, and then

lower ourselves gingerly into the pool, whose sides wave green and

long and soft and grasping with algae. And Mum won't kill spiders

because she says it will bring bad luck.

I tell her, "I'd say we have pretty rotten luck as it is."

"Then think how much worse it would be if we killed spiders."

I have my feet off the floor when I pee.

"Hurry up, man."

"Okay, okay."

"It's like Victoria Falls."

"I really had to go."

I have been holding my pee for a long, long time and staring out the

window to try and guess how close it is to morning. Maybe I could

hold it until morning. But then I notice that it is the

deep-black-sky quiet time of night, which is the halfway time between

the sun setting and the sun rising when even the night animals are

quiet-as if they, like day animals, take a break in the middle of

their work to rest. I can't hear Vanessa breathing; she has gone into

her deep middle-of-the-night silence. Dad is not snoring nor is he

shouting in his sleep. The baby is still in her crib but the smell of

her is warm and animal with wet nappy. It will be a long time until

morning.

Then Vanessa hands me the candle-"You keep boogies for me now"-and she pees.

"See, you had to go, too."

"Only 'cos you had to."

There is a hot breeze blowing through the window, the cold sinking

night air shifting the heat of the day up. The breeze has trapped

midday scents; the prevalent cloying of

the leach field, the green soap which has spilled out from the

laundry and landed on the patted-down red earth, the wood smoke from

the fires that heat our water, the boiled-meat smell of dog food.

We debate the merits of flushing the loo.

"We shouldn't waste the water." Even when there isn't a drought we

can't waste water, just in case one day there is a drought. Anyway,

Dad has said, "Steady on with the loo paper, you kids. And don't

flush the bloody loo all the time. The leach field can't handle it."

"But that's two pees in there."

"So? It's only pee."

"Agh sis, man, but it'll be smelly by tomorrow. And you peed as much

as a horse."

"It's not my fault."

"You can flush."

"You're taller."

"I'll hold the candle."

Van holds the candle high. I lower the toilet lid, stand on it and

lift up the block of hardwood that covers the cistern, and reach down

for the chain. Mum has glued a girlie-magazine picture to this block

of hardwood: a blond woman in few clothes, with breasts like naked

cow udders, and she's all arched in a strange pouty contortion, like

she's got backache. Which maybe she has, from the weight of the

udders. The picture is from Scope magazine.

We aren't allowed to look at Scope magazine.

"Why?"

"Because we aren't those sorts of people," says Mum.

"But we have a picture from Scope magazine on the loo lid."

"That's a joke."

"Oh." And then, "What sort of joke?"

"Stop twittering on."

A pause. "What sort of people are we, then?"

"We have breeding," says Mum firmly.

"Oh." Like the dairy cows and our special expensive bulls (who are

named Humani, Jack, and Bulawayo).

"Which is better than having money," she adds.

I look at her sideways, considering for a moment. "I'd rather have

money than breeding," I say.

Mum says, "Anyone can have money." As if it's something you might

pick up from the public toilets in OK Bazaar Grocery Store in Umtali.

"Ja, but we don't."

Mum sighs. "I'm trying to read, Bobo."

"Can you read to me?"

Mum sighs again. "All right," she says, "just one chapter." But it is

teatime before we look up from The Prince and the Pauper.

The loo gurgles and splutters, and then a torrent of water shakes

down, spilling slightly over the bowl.

"Sis, man," says Vanessa.

You never know what you're going to get with this loo. Sometimes it

refuses to flush at all and other times it's like this, water on your

feet.

I follow Vanessa back to the bedroom. The way candlelight falls,

we're walking into blackness, blinded by the flame of the candle,

unable to see our feet. So at the same moment we get the creeps, the

neck-prickling terrorist-under-the-bed creeps, and we abandon

ourselves to fear. The candle blows out. We skid into our room and

leap for the beds, our feet quickly tucked under us. We're both

panting, feeling foolish, trying to calm our breathing as if we

weren't scared at all.

Vanessa says, "There's a terrorist under your bed, I can see him."

"No you can't, how can you see him? The candle's out."

"Struze fact."

And I start to cry.

"Jeez, I'm only joking."

I cry harder.

"Shhh, man. You'll wake up Olivia. You'll wake up Mum and Dad."

Which is what I'm trying to do, without being shot. I want everyone

awake and noisy to chase away the terrorist-under-my-bed.

"Here," she says, "you can sleep with Fred if you stop crying."

So I stop crying and Vanessa pads over the bare cement floor and

brings me the cat, fast asleep in a snail-circle on her arms. She

puts him on the pillow and I put an arm over the vibrating, purring

body. Fred finds my earlobe and starts to suck. He's always sucked

our earlobes. Our hair is sucked into thin, slimy, knotted ropes near

the ears.

Mum says, "No wonder you have worms all the time."

I lie with my arms over the cat, awake and waiting. African dawn,

noisy with animals and the servants and Dad waking up and a tractor

coughing into life somewhere down at the workshop, clutters into the

room. The bantam hens start to crow and stretch, tumbling out of

their roosts in the tree behind the bathroom to peck at the

reflection of themselves in the window. Mum comes in smelling of

Vicks VapoRub and tea and warm bed and scoops the sleeping baby up to

her shoulder.

I can hear July setting tea on the veranda and I can smell the first,

fresh singe of Dad's morning cigarette. I balance Fred on my shoulder

and come out for tea: strong with no sugar, a splash of milk, the way

Mum likes it. Fred has a saucer of milk.

"Morning, Chookies," says Dad, not looking at me, smoking. He is

looking far off into the hills, where the border between Rhodesia and

Mozambique melts blue-gray, even in the pre-hazy clear of early

morning.

"Morning, Dad."

"Sleep all right?"

"Like a log," I tell him. "You?"

Dad grunts, stamps out his cigarette, drains his teacup, balances his

bush hat on his head, and strides out into the yard to make the most

of the little chill the night has left us with which to fight the

gathering soupy heat of day.

getting there:

zambia, 1987

To begin with, before Independence, I am at school with white

children only. "A" schools, they are called: superior schools with

the best teachers and facilities. The black children go to "C"

schools. In-between children who are neither black nor white (Indian

or a mixture of races) go to "B" schools.

The Indians and coloureds (who are neither completely this nor

completely that) and blacks are allowed into my school the year I

turn eleven, when the war is over. The blacks laugh at me when they

see me stripped naked after swimming or tennis, when my shoulders and

arms are angry sunburnt red.

"Argh! I smell roasting pork!" they shriek.

"Who fried the bacon?"

"Burning piggy!"

My God, I am the wrong color. The way I am burned by the sun,

scorched by flinging sand, prickled by heat. The way my skin erupts

in miniature volcanoes of protest in the presence of tsetse flies,

mosquitoes, ticks. The way I stand out against the khaki bush like a

large marshmallow to a gook with a gun. White. African. White-African.

"But what are you?" I am asked over and over again.

"Where are you from originally?"

I began then, embarking from a hot, dry boat.

Blinking bewildered from the sausage-gut of a train.

Arriving in Rhodesia, Africa. From Derbyshire, England. I was two

years old, startled and speaking toddler English. Lungs shocked by

thick, hot, humid air. Senses crushed under the weight of so many

stimuli.

I say, "I'm African." But not black.

And I say, "I was born in England," by mistake.

But, "I have lived in Rhodesia (which is now Zimbabwe) and in Malawi

(which used to be Nyasaland) and in Zambia (which used to be Northern

Rhodesia)."

And I add, "Now I live in America," through marriage.

And (full disclosure), "But my parents were born of Scottish and

English parents."

What does that make me?

Mum doesn't know who she is, either.

She stayed up all night once listening to Scottish music and crying.

"This music"-her nose twitches-"is so beautiful. It makes me homesick."

Mum has lived in Africa all but three years of her life.

"But this is your home."

"But my heart"-Mum attempts to thump her chest-"is Scottish."

Oh, fergodsake. "You hated England," I point out.

Mum nods, her head swinging, like a chicken with a broken neck.

"You're right," she says. "But I love Scotland."

"What," I ask, challenging, "do you love about Scotland?"

"Oh the . . . the . . ." Mum frowns at me, checks to see if I'm

tricking her. "The music," she says at last, and starts to weep

again. Mum hates Scotland. She hates drunk-driving laws and the cold.

The cold makes her cry, and then she comes down with malaria.

Her eyes are half-mast. That's what my sister and I call it when Mum

is drunk and her eyelids droop. Half-mast eyes. Like the flag at the

post office whenever someone important dies, which in Zambia, with

one thing and another, is every other week. Mum stares out at the

home paddocks where the cattle are coming in for their evening water

to the trough near the stables. The sun is full and heavy over the

hills that describe the Zambia-Zaire border. "Have a drink with me,

Bobo," she offers. She tries to pat the chair next to hers, misses,

and feebly slaps the air, her arm like a broken wing.

I shake my head. Ordinarily I don't mind getting softly drunk next to

the slowly collapsing heap that is Mum, but I have to go back to

boarding school the next day, nine hours by pickup across the border

to Zimbabwe. "I need to pack, Mum."

That afternoon Mum had spent hours wrapping thirty feet of electric

wire around the trees in the garden so that she could pick up the

World Service of the BBC. The signature tune crackled over the

syrup-yellow four o'clock light just as the sun was starting to hang

above the top of the msasa trees. " 'Lillibulero,' " Mum said.

"That's Irish."

"You're not Irish," I pointed out.

She said, "Never said I was." And then, follow-on thought, "Where's

the whisky?"

We must have heard "Lillibulero" thousands of times. Maybe millions.

Before and after every news broadcast. At the top of every hour.

Spluttering with static over the garden at home; incongruous from the

branches of acacia trees in campsites we have set up in the bush

across the countryside; singing from the bathroom in the evening.

But you never know what will set Mum off. Maybe it was "Lillibulero"

coinciding with the end of the afternoon, which is a rich, sweet,

cooling, melancholy time of day.

"Your Dad was English originally," I tell her, not liking the way

this is going.

She said, "It doesn't count. Scottish blood cancels English blood."

By the time she has drunk a quarter of a bottle of whisky, we have

lost reception from Bush House in London and the radio hisses to

itself from under its fringe of bougainvillea. Mum has pulled out her

old Scottish records. There are three of them. Three records of men

in kilts playing bagpipes. The photographs show them marching blindly

(how do they see under those dead-bear hats?) down misty Scottish

cobbled streets, their faces completely blocked by their massive

instruments. Mum turns the music up as loud as it will go, takes the

whisky out to the veranda, and sits cross-legged on a picnic chair,

humming and staring out at the night-blanketed farm.

This cross-leggedness is a hangover from the brief period in Mum's

life when she took up yoga from a book. Which was better than the

brief period in her life in which she explored the possibility of

converting to the Jehovah's Witnesses. And better than the time she

bought a book on belly-dancing at a rummage sale and tried out her

techniques on every bar north of the Limpopo River and south of the

equator.

The horses shuffle restlessly in their stables. The night apes scream

from the tops of the shimmering-leafed msasa trees. The dogs set up

in a chorus of barking and will not stop until we put them inside,

all except Mum's faithful spaniel, who will not leave her side even

when she's throwing what Dad calls a wobbly. Which is what this is: a

wobbly. The radio hisses and occasionally, drunkenly, bursts into

snatches of song (Spanish or Portuguese) or chatters in German, in

Afrikaans, or in an exaggerated American accent. "This is the Voice

of America." And then it swoops, "Beee-ooooeee!"

rhodesia, 1976

Mum says, "Don't come creeping into our room at night."

They sleep with loaded guns beside them on the bedside rugs. She

says, "Don't startle us when we're sleeping."

"Why not?"

"We might shoot you."

"Oh."

"By mistake."

"Okay." As it is, there seems a good enough chance of getting shot on

purpose. "Okay, I won't."

So if I wake in the night and need Mum and Dad, I call Vanessa,

because she isn't armed. "Van! Van, hey!" I hiss across the room

until she wakes up. And then Van has to light a candle and escort me

to the loo, where I pee sleepily into the flickering yellow light and

Van keeps the candle high, looking for snakes and scorpions and

baboon spiders.

Mum won't kill snakes because she says they help to keep the rats

down (but she rescued a nest of baby mice from the barns and left

them to grow in my cupboard, where they ate holes in the family's

winter jerseys). Mum won't kill scorpions either; she catches them

and lets them go free in the pool and Vanessa and I have to rake the

pool before we can swim. We fling the scorps as far as we can across

the brown and withering lawn, chase the ducks and geese out, and then

lower ourselves gingerly into the pool, whose sides wave green and

long and soft and grasping with algae. And Mum won't kill spiders

because she says it will bring bad luck.

I tell her, "I'd say we have pretty rotten luck as it is."

"Then think how much worse it would be if we killed spiders."

I have my feet off the floor when I pee.

"Hurry up, man."

"Okay, okay."

"It's like Victoria Falls."

"I really had to go."

I have been holding my pee for a long, long time and staring out the

window to try and guess how close it is to morning. Maybe I could

hold it until morning. But then I notice that it is the

deep-black-sky quiet time of night, which is the halfway time between

the sun setting and the sun rising when even the night animals are

quiet-as if they, like day animals, take a break in the middle of

their work to rest. I can't hear Vanessa breathing; she has gone into

her deep middle-of-the-night silence. Dad is not snoring nor is he

shouting in his sleep. The baby is still in her crib but the smell of

her is warm and animal with wet nappy. It will be a long time until

morning.

Then Vanessa hands me the candle-"You keep boogies for me now"-and she pees.

"See, you had to go, too."

"Only 'cos you had to."

There is a hot breeze blowing through the window, the cold sinking

night air shifting the heat of the day up. The breeze has trapped

midday scents; the prevalent cloying of

the leach field, the green soap which has spilled out from the

laundry and landed on the patted-down red earth, the wood smoke from

the fires that heat our water, the boiled-meat smell of dog food.

We debate the merits of flushing the loo.

"We shouldn't waste the water." Even when there isn't a drought we

can't waste water, just in case one day there is a drought. Anyway,

Dad has said, "Steady on with the loo paper, you kids. And don't

flush the bloody loo all the time. The leach field can't handle it."

"But that's two pees in there."

"So? It's only pee."

"Agh sis, man, but it'll be smelly by tomorrow. And you peed as much

as a horse."

"It's not my fault."

"You can flush."

"You're taller."

"I'll hold the candle."

Van holds the candle high. I lower the toilet lid, stand on it and

lift up the block of hardwood that covers the cistern, and reach down

for the chain. Mum has glued a girlie-magazine picture to this block

of hardwood: a blond woman in few clothes, with breasts like naked

cow udders, and she's all arched in a strange pouty contortion, like

she's got backache. Which maybe she has, from the weight of the

udders. The picture is from Scope magazine.

We aren't allowed to look at Scope magazine.

"Why?"

"Because we aren't those sorts of people," says Mum.

"But we have a picture from Scope magazine on the loo lid."

"That's a joke."

"Oh." And then, "What sort of joke?"

"Stop twittering on."

A pause. "What sort of people are we, then?"

"We have breeding," says Mum firmly.

"Oh." Like the dairy cows and our special expensive bulls (who are

named Humani, Jack, and Bulawayo).

"Which is better than having money," she adds.

I look at her sideways, considering for a moment. "I'd rather have

money than breeding," I say.

Mum says, "Anyone can have money." As if it's something you might

pick up from the public toilets in OK Bazaar Grocery Store in Umtali.

"Ja, but we don't."

Mum sighs. "I'm trying to read, Bobo."

"Can you read to me?"

Mum sighs again. "All right," she says, "just one chapter." But it is

teatime before we look up from The Prince and the Pauper.

The loo gurgles and splutters, and then a torrent of water shakes

down, spilling slightly over the bowl.

"Sis, man," says Vanessa.

You never know what you're going to get with this loo. Sometimes it

refuses to flush at all and other times it's like this, water on your

feet.

I follow Vanessa back to the bedroom. The way candlelight falls,

we're walking into blackness, blinded by the flame of the candle,

unable to see our feet. So at the same moment we get the creeps, the

neck-prickling terrorist-under-the-bed creeps, and we abandon

ourselves to fear. The candle blows out. We skid into our room and

leap for the beds, our feet quickly tucked under us. We're both

panting, feeling foolish, trying to calm our breathing as if we

weren't scared at all.

Vanessa says, "There's a terrorist under your bed, I can see him."

"No you can't, how can you see him? The candle's out."

"Struze fact."

And I start to cry.

"Jeez, I'm only joking."

I cry harder.

"Shhh, man. You'll wake up Olivia. You'll wake up Mum and Dad."

Which is what I'm trying to do, without being shot. I want everyone

awake and noisy to chase away the terrorist-under-my-bed.

"Here," she says, "you can sleep with Fred if you stop crying."

So I stop crying and Vanessa pads over the bare cement floor and

brings me the cat, fast asleep in a snail-circle on her arms. She

puts him on the pillow and I put an arm over the vibrating, purring

body. Fred finds my earlobe and starts to suck. He's always sucked

our earlobes. Our hair is sucked into thin, slimy, knotted ropes near

the ears.

Mum says, "No wonder you have worms all the time."

I lie with my arms over the cat, awake and waiting. African dawn,

noisy with animals and the servants and Dad waking up and a tractor

coughing into life somewhere down at the workshop, clutters into the

room. The bantam hens start to crow and stretch, tumbling out of

their roosts in the tree behind the bathroom to peck at the

reflection of themselves in the window. Mum comes in smelling of

Vicks VapoRub and tea and warm bed and scoops the sleeping baby up to

her shoulder.

I can hear July setting tea on the veranda and I can smell the first,

fresh singe of Dad's morning cigarette. I balance Fred on my shoulder

and come out for tea: strong with no sugar, a splash of milk, the way

Mum likes it. Fred has a saucer of milk.

"Morning, Chookies," says Dad, not looking at me, smoking. He is

looking far off into the hills, where the border between Rhodesia and

Mozambique melts blue-gray, even in the pre-hazy clear of early

morning.

"Morning, Dad."

"Sleep all right?"

"Like a log," I tell him. "You?"

Dad grunts, stamps out his cigarette, drains his teacup, balances his

bush hat on his head, and strides out into the yard to make the most

of the little chill the night has left us with which to fight the

gathering soupy heat of day.

getting there:

zambia, 1987

To begin with, before Independence, I am at school with white

children only. "A" schools, they are called: superior schools with

the best teachers and facilities. The black children go to "C"

schools. In-between children who are neither black nor white (Indian

or a mixture of races) go to "B" schools.

The Indians and coloureds (who are neither completely this nor

completely that) and blacks are allowed into my school the year I

turn eleven, when the war is over. The blacks laugh at me when they

see me stripped naked after swimming or tennis, when my shoulders and

arms are angry sunburnt red.

"Argh! I smell roasting pork!" they shriek.

"Who fried the bacon?"

"Burning piggy!"

My God, I am the wrong color. The way I am burned by the sun,

scorched by flinging sand, prickled by heat. The way my skin erupts

in miniature volcanoes of protest in the presence of tsetse flies,

mosquitoes, ticks. The way I stand out against the khaki bush like a

large marshmallow to a gook with a gun. White. African. White-African.

"But what are you?" I am asked over and over again.

"Where are you from originally?"

I began then, embarking from a hot, dry boat.

Blinking bewildered from the sausage-gut of a train.

Arriving in Rhodesia, Africa. From Derbyshire, England. I was two

years old, startled and speaking toddler English. Lungs shocked by

thick, hot, humid air. Senses crushed under the weight of so many

stimuli.

I say, "I'm African." But not black.

And I say, "I was born in England," by mistake.

But, "I have lived in Rhodesia (which is now Zimbabwe) and in Malawi

(which used to be Nyasaland) and in Zambia (which used to be Northern

Rhodesia)."

And I add, "Now I live in America," through marriage.

And (full disclosure), "But my parents were born of Scottish and

English parents."

What does that make me?

Mum doesn't know who she is, either.

She stayed up all night once listening to Scottish music and crying.

"This music"-her nose twitches-"is so beautiful. It makes me homesick."

Mum has lived in Africa all but three years of her life.

"But this is your home."

"But my heart"-Mum attempts to thump her chest-"is Scottish."

Oh, fergodsake. "You hated England," I point out.

Mum nods, her head swinging, like a chicken with a broken neck.

"You're right," she says. "But I love Scotland."

"What," I ask, challenging, "do you love about Scotland?"

"Oh the . . . the . . ." Mum frowns at me, checks to see if I'm

tricking her. "The music," she says at last, and starts to weep

again. Mum hates Scotland. She hates drunk-driving laws and the cold.

The cold makes her cry, and then she comes down with malaria.

Her eyes are half-mast. That's what my sister and I call it when Mum

is drunk and her eyelids droop. Half-mast eyes. Like the flag at the

post office whenever someone important dies, which in Zambia, with

one thing and another, is every other week. Mum stares out at the

home paddocks where the cattle are coming in for their evening water

to the trough near the stables. The sun is full and heavy over the

hills that describe the Zambia-Zaire border. "Have a drink with me,

Bobo," she offers. She tries to pat the chair next to hers, misses,

and feebly slaps the air, her arm like a broken wing.

I shake my head. Ordinarily I don't mind getting softly drunk next to

the slowly collapsing heap that is Mum, but I have to go back to

boarding school the next day, nine hours by pickup across the border

to Zimbabwe. "I need to pack, Mum."

That afternoon Mum had spent hours wrapping thirty feet of electric

wire around the trees in the garden so that she could pick up the

World Service of the BBC. The signature tune crackled over the

syrup-yellow four o'clock light just as the sun was starting to hang

above the top of the msasa trees. " 'Lillibulero,' " Mum said.

"That's Irish."

"You're not Irish," I pointed out.

She said, "Never said I was." And then, follow-on thought, "Where's

the whisky?"

We must have heard "Lillibulero" thousands of times. Maybe millions.

Before and after every news broadcast. At the top of every hour.

Spluttering with static over the garden at home; incongruous from the

branches of acacia trees in campsites we have set up in the bush

across the countryside; singing from the bathroom in the evening.

But you never know what will set Mum off. Maybe it was "Lillibulero"

coinciding with the end of the afternoon, which is a rich, sweet,

cooling, melancholy time of day.

"Your Dad was English originally," I tell her, not liking the way

this is going.

She said, "It doesn't count. Scottish blood cancels English blood."

By the time she has drunk a quarter of a bottle of whisky, we have

lost reception from Bush House in London and the radio hisses to

itself from under its fringe of bougainvillea. Mum has pulled out her

old Scottish records. There are three of them. Three records of men

in kilts playing bagpipes. The photographs show them marching blindly

(how do they see under those dead-bear hats?) down misty Scottish

cobbled streets, their faces completely blocked by their massive

instruments. Mum turns the music up as loud as it will go, takes the

whisky out to the veranda, and sits cross-legged on a picnic chair,

humming and staring out at the night-blanketed farm.

This cross-leggedness is a hangover from the brief period in Mum's

life when she took up yoga from a book. Which was better than the

brief period in her life in which she explored the possibility of

converting to the Jehovah's Witnesses. And better than the time she

bought a book on belly-dancing at a rummage sale and tried out her

techniques on every bar north of the Limpopo River and south of the

equator.

The horses shuffle restlessly in their stables. The night apes scream

from the tops of the shimmering-leafed msasa trees. The dogs set up

in a chorus of barking and will not stop until we put them inside,

all except Mum's faithful spaniel, who will not leave her side even

when she's throwing what Dad calls a wobbly. Which is what this is: a

wobbly. The radio hisses and occasionally, drunkenly, bursts into

snatches of song (Spanish or Portuguese) or chatters in German, in

Afrikaans, or in an exaggerated American accent. "This is the Voice

of America." And then it swoops, "Beee-ooooeee!"

Recenzii

“This is not a book you read just once, but a tale of terrible beauty to get lost in over and over.” —Newsweek

“By turns mischievous and openhearted, earthy and soaring . . . hair-raising, horrific, and thrilling.”—The New Yorker

“Ms. Fuller gives us . . . the Africa she knew as a girl, a place of cruel politics, violent heat and startling beauty, a land she makes vivid in all its ‘incongruous, lawless, joyful, violent, upside-down, illogical certainty.’” —The New York Times

“Vivid, insightful and sly . . . Bottom line: Out of Africa, brilliantly.”—People

“By turns mischievous and openhearted, earthy and soaring . . . hair-raising, horrific, and thrilling.”—The New Yorker

“Ms. Fuller gives us . . . the Africa she knew as a girl, a place of cruel politics, violent heat and startling beauty, a land she makes vivid in all its ‘incongruous, lawless, joyful, violent, upside-down, illogical certainty.’” —The New York Times

“Vivid, insightful and sly . . . Bottom line: Out of Africa, brilliantly.”—People