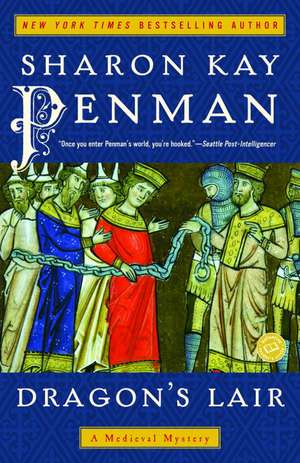

Dragon's Lair: Ballantine Reader's Circle

Autor Sharon Kay Penmanen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 oct 2004 – vârsta de la 14 până la 18 ani

When a ransom payment vanishes, Eleanor hastily dispatches young Justin de Quincy to investigate. In wild, beautiful Wales, his devotion to the queen will be supremely tested–as an arrogant border earl, a cocky Welsh prince, an enchanting lady, and a traitor of the deepest dye welcome him with false smiles and deadly conspiracies. The queen’s treasure is nowhere to be found, but assassins are everywhere . . . and blood runs red in the dragon’s lair.

Din seria Ballantine Reader's Circle

-

Preț: 97.74 lei

Preț: 97.74 lei -

Preț: 120.15 lei

Preț: 120.15 lei -

Preț: 107.27 lei

Preț: 107.27 lei -

Preț: 121.12 lei

Preț: 121.12 lei -

Preț: 126.98 lei

Preț: 126.98 lei -

Preț: 113.15 lei

Preț: 113.15 lei -

Preț: 115.32 lei

Preț: 115.32 lei -

Preț: 109.66 lei

Preț: 109.66 lei -

Preț: 102.38 lei

Preț: 102.38 lei -

Preț: 129.37 lei

Preț: 129.37 lei -

Preț: 114.71 lei

Preț: 114.71 lei -

Preț: 65.81 lei

Preț: 65.81 lei -

Preț: 116.57 lei

Preț: 116.57 lei -

Preț: 91.96 lei

Preț: 91.96 lei -

Preț: 90.35 lei

Preț: 90.35 lei -

Preț: 120.71 lei

Preț: 120.71 lei -

Preț: 116.64 lei

Preț: 116.64 lei -

Preț: 139.70 lei

Preț: 139.70 lei -

Preț: 110.76 lei

Preț: 110.76 lei -

Preț: 127.70 lei

Preț: 127.70 lei -

Preț: 116.55 lei

Preț: 116.55 lei -

Preț: 112.52 lei

Preț: 112.52 lei -

Preț: 109.71 lei

Preț: 109.71 lei -

Preț: 111.51 lei

Preț: 111.51 lei -

Preț: 111.17 lei

Preț: 111.17 lei -

Preț: 121.22 lei

Preț: 121.22 lei -

Preț: 89.48 lei

Preț: 89.48 lei -

Preț: 106.23 lei

Preț: 106.23 lei -

Preț: 123.90 lei

Preț: 123.90 lei -

Preț: 118.73 lei

Preț: 118.73 lei -

Preț: 126.88 lei

Preț: 126.88 lei -

Preț: 110.96 lei

Preț: 110.96 lei -

Preț: 128.86 lei

Preț: 128.86 lei -

Preț: 124.72 lei

Preț: 124.72 lei -

Preț: 128.86 lei

Preț: 128.86 lei -

Preț: 122.76 lei

Preț: 122.76 lei -

Preț: 122.64 lei

Preț: 122.64 lei -

Preț: 133.06 lei

Preț: 133.06 lei -

Preț: 132.06 lei

Preț: 132.06 lei -

Preț: 109.73 lei

Preț: 109.73 lei -

Preț: 93.82 lei

Preț: 93.82 lei -

Preț: 101.06 lei

Preț: 101.06 lei -

Preț: 85.08 lei

Preț: 85.08 lei -

Preț: 85.13 lei

Preț: 85.13 lei -

Preț: 79.16 lei

Preț: 79.16 lei -

Preț: 88.39 lei

Preț: 88.39 lei -

Preț: 99.83 lei

Preț: 99.83 lei -

Preț: 92.83 lei

Preț: 92.83 lei -

Preț: 87.43 lei

Preț: 87.43 lei

Preț: 112.64 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 169

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.55€ • 22.51$ • 17.80£

21.55€ • 22.51$ • 17.80£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 25 martie-08 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345434234

ISBN-10: 0345434234

Pagini: 352

Dimensiuni: 135 x 203 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Ediția:Ballantine Book.

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

Seria Ballantine Reader's Circle

ISBN-10: 0345434234

Pagini: 352

Dimensiuni: 135 x 203 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Ediția:Ballantine Book.

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

Seria Ballantine Reader's Circle

Extras

CHAPTER 1

July 1193 Westminster, England

Walking in the gardens of the royal palace on a sultry, overcast summer afternoon, Claudine de Loudun recognized for the first time that she feared the queen. This should not have been so surprising to her, for the queen in question was Eleanor, Dowager Queen of England, Duchess of Aquitaine, one-time Queen of France. Burning as brightly as a comet in her youth, Eleanor had shocked and fascinated and outraged, a beautiful, willful woman who’d wed two kings, taken the cross, given birth to ten children, and dared to lust after power as a man might. But she’d survived scandal, heartbreak, and insurrection, even sixteen years as her husband Henry’s prisoner.

The older Eleanor was wiser and less reckless, a woman who’d learned to weigh both words and consequences. Her ambitions had always been dynastic, and in her twilight years she was expending all of her considerable intelligence, political guile, and tenacity in the service of her son Richard. She was respected now, even revered in some quarters, for her sound advice and pragmatic understanding of statecraft, and few appreciated the irony—that this woman who’d lived much of her life as a royal rebel should be acclaimed as a stabilizing influence upon the brash, impulsive Richard.

To outward appearances, it seemed as if the aged queen had repudiated the carefree and careless girl she’d once been, but Claudine knew better. Eleanor’s tactics had changed, not her nature. She was worldly, curious, utterly charming when she chose to be, prideful, stubborn, calculating, and still hungry for all that life had to offer. She had a remarkable memory untainted by age, and although she might forgive wrongs, she never forgot them. As Claudine was belatedly acknowledging, she could be a formidable enemy.

Claudine was not a fool, even if she had done more than her share of foolish things. It was not that she’d underestimated the queen, but rather that she’d overestimated her own ability to swim in such turbulent waters. It had seemed harmless enough in the beginning. What did it matter if she shared court gossip and rumors with the queen’s youngest son? She had seen it as a game, not a betrayal, just as she’d seen herself as John’s confederate, not his spy. How had it all gone so wrong? She still was not sure. But there was no denying that the stakes had suddenly become life or death. Richard languished in a German prison. John was being accused of treason. The queen was sick with fear for her eldest son and vowing vengeance upon those who would deny Richard his freedom. And Claudine was in the worst plight of all, pregnant and unwed, facing both the perils of the birthing chamber and the danger of disgrace and scandal.

She’d never worried about incurring Eleanor’s animosity before, confident of her own power to beguile, putting too much trust in her blood ties to the queen, distant though they might be. But in this fragrant, trellised garden, she was suddenly and acutely aware of how vulnerable she truly was. It was such a demoralizing realization that she quickly reminded herself how understanding the queen had been about her pregnancy. She’d feared that Eleanor would turn her out, letting all know of her shame. Instead, the queen had offered to help. So why, then, did she feel such unease?

She glanced sideways at the other woman, and then away. She’d often thought the queen had cat eyes, greenish-gold and inscrutable, eyes that seemed able to see into the inner recesses of her soul, to strip away her secrets, one by one. Claudine bit her lip, keeping her own eyes downcast, for she had so many secrets.

Eleanor was aware of the young woman’s edginess, and it afforded her some grim satisfaction. She bore Claudine no grudge for allowing herself to become entangled in John’s web; she’d had too many betrayals in her life to be wounded by one so small. And so once she’d discovered Claudine’s complicity in her son’s scheming, she’d been content to keep that knowledge secret, reasoning that a known spy was a defanged snake. She’d even used the unwitting Claudine to pass on misinformation from time to time. But if she felt no desire for vengeance, neither did she have sympathy for Claudine’s predicament. Every pleasure in this world came with a price, be it a dalliance in conspiracy or one in bed.

Glancing about to make sure none of her other attendants were within earshot, Eleanor asked the girl if she was still queasy. When Claudine swallowed and swore that she no longer felt poorly, Eleanor gave her a skeptical scrutiny. “Why, then, is your face the color of newly skimmed milk? There is no need to pretend with me, child. Only men could call a pregnancy ‘easy,’ but some are undoubtedly more troublesome than others. For me, it was my last. There were days when even water could unsettle my stomach. I’ve sailed in some fierce storms, but God’s Truth, I was never so greensick as when I was carrying John.”

Claudine’s eyelashes flickered, no more than that. But she could not keep the blood from rising in her face and throat. Watching as her pallor was submerged in a flood of color, Eleanor smiled slyly. This was new, like an involuntary twitch or a hiccup, this sudden discomfort whenever John’s name was mentioned. Not for the first time, Eleanor wondered who had truly fathered Claudine’s child. Was it Justin de Quincy as she claimed? Or was it John?

“I think it is time,” she said, “for you to withdraw to the nunnery at Godstow.”

Claudine nodded reluctantly. This was the plan, with cover stories fabricated for the court and her family back in Aquitaine. She should have gone a fortnight ago, but she’d found excuses to delay, dreading the loneliness and seclusion and boredom of the coming months. “I suppose so,” she admitted, sounding so forlorn that Eleanor experienced an involuntary pang of empathy; she knew better than most the onus of confinement. It was true that this confinement was by choice and temporary, but Eleanor could not help identifying with Claudine’s aversion to the religious life. There had been times in her past when she’d feared being shut up in some remote, obscure convent for the rest of her days, forgotten by all but her gaolers and God.

“I will speak with Sir Nicholas this eve,” she said briskly, determined not to soften toward this foolhardy, unhappy girl. “The arrangements have all been made. It remains only for you to settle in at Godstow.”

“Sir Nicholas de Mydden?” Claudine echoed in dismay. “But Justin was to escort me to the nunnery.”

“Justin cannot—”

“Madame, he promised me!” Claudine was so flustered that she did not even realize she’d interrupted the queen. Lowering her voice hastily lest they attract attention, she said coaxingly, “Surely you understand why I would prefer Justin’s company, Your Grace. I know I can trust him. And . . . and he wants to accompany me. This child is his, after all.”

Eleanor looked into Claudine’s flushed, distraught face, striving for patience. “Well, this is one promise Justin cannot keep. He is away from the court, and I know not when he will return. As for Nicholas, he is no gossipmonger.” Unable to resist adding, “Those in my service know the value I place upon loyalty.”

Claudine’s lashes fluttered down again, veiling her eyes. After a moment, she said meekly, “Forgive my boldness, madame. It was not my intent to argue with you. If you have confidence in Sir Nicholas’s discretion, then so do I. But could I not wait till week’s end? Mayhap Justin will be back by then.”

She took Eleanor’s shrug for assent and fell in step beside the queen as they cut across the grassy mead. “I did not even know Justin was gone, for he did not bid me farewell.”

She sounded both plaintive and aggrieved, and Eleanor found herself thinking that Justin might be fortunate that he was not considered a suitable husband for this pampered young kinswoman of hers. It would be no easy task, keeping Claudine de Loudun content.

“Madame . . . it is not my intent to pry,” Claudine said, with such pious prevarication that Eleanor rolled her eyes skyward. “Whatever Justin’s mission for you may be, it is not for me to question it. I would ask this, though. Can you at least tell me if he is in any danger?”

Eleanor paused, considering. Her first impulse was to give the girl the reassurance she sought. But the truth was that whenever her son John was involved, there was bound to be danger.

It was a sparse turnout for a hanging. Usually the citizens of Winchester thronged to the gallows out on Andover Road, eager to watch as a felon paid the ultimate price for his earthly sins. Luke de Marston, the under-sheriff of Hampshire, could remember hangings that rivaled the St Giles Fair, with venders hawking meat pies and children getting underfoot and cutpurses on the prowl for unwary victims. But the doomed soul being dragged from the cart was too small a fish to attract a large crowd, a criminal by happenstance rather than choice.

The few men and women who’d bothered to show up were further disappointed by the demeanor of the culprit. They expected bravado and defiance from their villains, or at the very least, stoical self-control. But this prisoner was obviously terrified, whimpering and trembling so violently that he had to be assisted up the gallows steps. People were beginning to turn away in disgust even before the rope was tightened around his neck.

Luke’s deputy shared their dissatisfaction, for he believed that a condemned man owed his audience a better show than this. “Pitiful,” he said, shaking his head in disapproval. “Remember how the Fleming died, cursing God with his last breath?”

Luke remembered. Gilbert the Fleming had been one of Winchester’s most notorious outlaws, as brutal as he was elusive, evading capture again and again until he’d been brought down by Luke and the queen’s man, Justin de Quincy. His hanging had been a holiday.

“Luke.”

July 1193 Westminster, England

Walking in the gardens of the royal palace on a sultry, overcast summer afternoon, Claudine de Loudun recognized for the first time that she feared the queen. This should not have been so surprising to her, for the queen in question was Eleanor, Dowager Queen of England, Duchess of Aquitaine, one-time Queen of France. Burning as brightly as a comet in her youth, Eleanor had shocked and fascinated and outraged, a beautiful, willful woman who’d wed two kings, taken the cross, given birth to ten children, and dared to lust after power as a man might. But she’d survived scandal, heartbreak, and insurrection, even sixteen years as her husband Henry’s prisoner.

The older Eleanor was wiser and less reckless, a woman who’d learned to weigh both words and consequences. Her ambitions had always been dynastic, and in her twilight years she was expending all of her considerable intelligence, political guile, and tenacity in the service of her son Richard. She was respected now, even revered in some quarters, for her sound advice and pragmatic understanding of statecraft, and few appreciated the irony—that this woman who’d lived much of her life as a royal rebel should be acclaimed as a stabilizing influence upon the brash, impulsive Richard.

To outward appearances, it seemed as if the aged queen had repudiated the carefree and careless girl she’d once been, but Claudine knew better. Eleanor’s tactics had changed, not her nature. She was worldly, curious, utterly charming when she chose to be, prideful, stubborn, calculating, and still hungry for all that life had to offer. She had a remarkable memory untainted by age, and although she might forgive wrongs, she never forgot them. As Claudine was belatedly acknowledging, she could be a formidable enemy.

Claudine was not a fool, even if she had done more than her share of foolish things. It was not that she’d underestimated the queen, but rather that she’d overestimated her own ability to swim in such turbulent waters. It had seemed harmless enough in the beginning. What did it matter if she shared court gossip and rumors with the queen’s youngest son? She had seen it as a game, not a betrayal, just as she’d seen herself as John’s confederate, not his spy. How had it all gone so wrong? She still was not sure. But there was no denying that the stakes had suddenly become life or death. Richard languished in a German prison. John was being accused of treason. The queen was sick with fear for her eldest son and vowing vengeance upon those who would deny Richard his freedom. And Claudine was in the worst plight of all, pregnant and unwed, facing both the perils of the birthing chamber and the danger of disgrace and scandal.

She’d never worried about incurring Eleanor’s animosity before, confident of her own power to beguile, putting too much trust in her blood ties to the queen, distant though they might be. But in this fragrant, trellised garden, she was suddenly and acutely aware of how vulnerable she truly was. It was such a demoralizing realization that she quickly reminded herself how understanding the queen had been about her pregnancy. She’d feared that Eleanor would turn her out, letting all know of her shame. Instead, the queen had offered to help. So why, then, did she feel such unease?

She glanced sideways at the other woman, and then away. She’d often thought the queen had cat eyes, greenish-gold and inscrutable, eyes that seemed able to see into the inner recesses of her soul, to strip away her secrets, one by one. Claudine bit her lip, keeping her own eyes downcast, for she had so many secrets.

Eleanor was aware of the young woman’s edginess, and it afforded her some grim satisfaction. She bore Claudine no grudge for allowing herself to become entangled in John’s web; she’d had too many betrayals in her life to be wounded by one so small. And so once she’d discovered Claudine’s complicity in her son’s scheming, she’d been content to keep that knowledge secret, reasoning that a known spy was a defanged snake. She’d even used the unwitting Claudine to pass on misinformation from time to time. But if she felt no desire for vengeance, neither did she have sympathy for Claudine’s predicament. Every pleasure in this world came with a price, be it a dalliance in conspiracy or one in bed.

Glancing about to make sure none of her other attendants were within earshot, Eleanor asked the girl if she was still queasy. When Claudine swallowed and swore that she no longer felt poorly, Eleanor gave her a skeptical scrutiny. “Why, then, is your face the color of newly skimmed milk? There is no need to pretend with me, child. Only men could call a pregnancy ‘easy,’ but some are undoubtedly more troublesome than others. For me, it was my last. There were days when even water could unsettle my stomach. I’ve sailed in some fierce storms, but God’s Truth, I was never so greensick as when I was carrying John.”

Claudine’s eyelashes flickered, no more than that. But she could not keep the blood from rising in her face and throat. Watching as her pallor was submerged in a flood of color, Eleanor smiled slyly. This was new, like an involuntary twitch or a hiccup, this sudden discomfort whenever John’s name was mentioned. Not for the first time, Eleanor wondered who had truly fathered Claudine’s child. Was it Justin de Quincy as she claimed? Or was it John?

“I think it is time,” she said, “for you to withdraw to the nunnery at Godstow.”

Claudine nodded reluctantly. This was the plan, with cover stories fabricated for the court and her family back in Aquitaine. She should have gone a fortnight ago, but she’d found excuses to delay, dreading the loneliness and seclusion and boredom of the coming months. “I suppose so,” she admitted, sounding so forlorn that Eleanor experienced an involuntary pang of empathy; she knew better than most the onus of confinement. It was true that this confinement was by choice and temporary, but Eleanor could not help identifying with Claudine’s aversion to the religious life. There had been times in her past when she’d feared being shut up in some remote, obscure convent for the rest of her days, forgotten by all but her gaolers and God.

“I will speak with Sir Nicholas this eve,” she said briskly, determined not to soften toward this foolhardy, unhappy girl. “The arrangements have all been made. It remains only for you to settle in at Godstow.”

“Sir Nicholas de Mydden?” Claudine echoed in dismay. “But Justin was to escort me to the nunnery.”

“Justin cannot—”

“Madame, he promised me!” Claudine was so flustered that she did not even realize she’d interrupted the queen. Lowering her voice hastily lest they attract attention, she said coaxingly, “Surely you understand why I would prefer Justin’s company, Your Grace. I know I can trust him. And . . . and he wants to accompany me. This child is his, after all.”

Eleanor looked into Claudine’s flushed, distraught face, striving for patience. “Well, this is one promise Justin cannot keep. He is away from the court, and I know not when he will return. As for Nicholas, he is no gossipmonger.” Unable to resist adding, “Those in my service know the value I place upon loyalty.”

Claudine’s lashes fluttered down again, veiling her eyes. After a moment, she said meekly, “Forgive my boldness, madame. It was not my intent to argue with you. If you have confidence in Sir Nicholas’s discretion, then so do I. But could I not wait till week’s end? Mayhap Justin will be back by then.”

She took Eleanor’s shrug for assent and fell in step beside the queen as they cut across the grassy mead. “I did not even know Justin was gone, for he did not bid me farewell.”

She sounded both plaintive and aggrieved, and Eleanor found herself thinking that Justin might be fortunate that he was not considered a suitable husband for this pampered young kinswoman of hers. It would be no easy task, keeping Claudine de Loudun content.

“Madame . . . it is not my intent to pry,” Claudine said, with such pious prevarication that Eleanor rolled her eyes skyward. “Whatever Justin’s mission for you may be, it is not for me to question it. I would ask this, though. Can you at least tell me if he is in any danger?”

Eleanor paused, considering. Her first impulse was to give the girl the reassurance she sought. But the truth was that whenever her son John was involved, there was bound to be danger.

It was a sparse turnout for a hanging. Usually the citizens of Winchester thronged to the gallows out on Andover Road, eager to watch as a felon paid the ultimate price for his earthly sins. Luke de Marston, the under-sheriff of Hampshire, could remember hangings that rivaled the St Giles Fair, with venders hawking meat pies and children getting underfoot and cutpurses on the prowl for unwary victims. But the doomed soul being dragged from the cart was too small a fish to attract a large crowd, a criminal by happenstance rather than choice.

The few men and women who’d bothered to show up were further disappointed by the demeanor of the culprit. They expected bravado and defiance from their villains, or at the very least, stoical self-control. But this prisoner was obviously terrified, whimpering and trembling so violently that he had to be assisted up the gallows steps. People were beginning to turn away in disgust even before the rope was tightened around his neck.

Luke’s deputy shared their dissatisfaction, for he believed that a condemned man owed his audience a better show than this. “Pitiful,” he said, shaking his head in disapproval. “Remember how the Fleming died, cursing God with his last breath?”

Luke remembered. Gilbert the Fleming had been one of Winchester’s most notorious outlaws, as brutal as he was elusive, evading capture again and again until he’d been brought down by Luke and the queen’s man, Justin de Quincy. His hanging had been a holiday.

“Luke.”

Recenzii

“Once you enter Penman’s world, you’re hooked.”

–Seattle Post-Intelligencer

“Penman writes about the medieval world and its people with vigor, compassion, and clarity.”

–San Francisco Chronicle

“Welcome to twelfth-century English and Welsh politics by way of this riveting and rich mystery novel.”

–Booklist

“A polished and absorbing historical mystery."

–Kirkus Reviews

–Seattle Post-Intelligencer

“Penman writes about the medieval world and its people with vigor, compassion, and clarity.”

–San Francisco Chronicle

“Welcome to twelfth-century English and Welsh politics by way of this riveting and rich mystery novel.”

–Booklist

“A polished and absorbing historical mystery."

–Kirkus Reviews

Descriere

First introduced in "The Queen's Man," Justin de Quincy, resourceful special agent to Dowager Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine, investigates the disappearance of a ransom meant to free King Richard from the clutches of the German emperor.

Notă biografică

Sharon Kay Penman