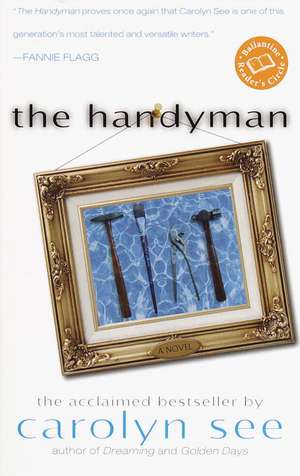

The Handyman: Ballantine Reader's Circle

Autor Carolyn Seeen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2000

The Handyman is the story of Bob Hampton, an aspiring young painter who has had to face the humbling fact that he doesn't know what to paint. And how are you supposed to be an artist in this world if you don't have a vision? Bob trades in his artist's palette for a minivan full of house paints, hammers, and nails, and sets about earning a little cash as a handyman.

Although he turns out to be very bad at fixing the things he's hired to fix, Bob demonstrates quite a knack for fixing the lives of the people around him. In the midst of his jerry-built repairs and inspired home improvements, Bob meets an extraordinary cast of characters--rendered in all their delightful eccentricity and human frailty as only Carolyn See can-each of whom shows Bob the true scope of his own remarkable talent. There's Angela Landry, a housewife with far too much time on her hands, a sexpot of a stepdaughter, and a son in need of attention; Jamie Walker, whose allergy-prone and ADD-afflicted children keep a menagerie of scaly pets that far exceed Jamie's managerial skills; Valerie LeClerc, older, sadder, and certainly wiser than Bob; and Hank and Ben, who leave a narrow-minded Midwest only to find unremitting illness and isolation in the California of their dreams.

Replete with stunning images and all of Carolyn See's trademark humor and wisdom, The Handyman depicts the countless ways in which our lives are intertwined and the profound effects we can have on one another. It is the kind of surprising and miraculously uplifting novel we have come to expect from the woman Diane Johnson has called "one of our most important writers."

From the Hardcover edition.

Din seria Ballantine Reader's Circle

-

Preț: 97.74 lei

Preț: 97.74 lei -

Preț: 120.15 lei

Preț: 120.15 lei -

Preț: 107.27 lei

Preț: 107.27 lei -

Preț: 121.12 lei

Preț: 121.12 lei -

Preț: 126.98 lei

Preț: 126.98 lei -

Preț: 113.15 lei

Preț: 113.15 lei -

Preț: 115.32 lei

Preț: 115.32 lei -

Preț: 107.17 lei

Preț: 107.17 lei -

Preț: 102.38 lei

Preț: 102.38 lei -

Preț: 129.37 lei

Preț: 129.37 lei -

Preț: 114.71 lei

Preț: 114.71 lei -

Preț: 65.81 lei

Preț: 65.81 lei -

Preț: 116.57 lei

Preț: 116.57 lei -

Preț: 91.96 lei

Preț: 91.96 lei -

Preț: 90.35 lei

Preț: 90.35 lei -

Preț: 120.71 lei

Preț: 120.71 lei -

Preț: 116.64 lei

Preț: 116.64 lei -

Preț: 139.70 lei

Preț: 139.70 lei -

Preț: 110.76 lei

Preț: 110.76 lei -

Preț: 127.70 lei

Preț: 127.70 lei -

Preț: 116.55 lei

Preț: 116.55 lei -

Preț: 112.52 lei

Preț: 112.52 lei -

Preț: 109.71 lei

Preț: 109.71 lei -

Preț: 111.51 lei

Preț: 111.51 lei -

Preț: 121.22 lei

Preț: 121.22 lei -

Preț: 89.48 lei

Preț: 89.48 lei -

Preț: 106.23 lei

Preț: 106.23 lei -

Preț: 123.90 lei

Preț: 123.90 lei -

Preț: 118.73 lei

Preț: 118.73 lei -

Preț: 126.88 lei

Preț: 126.88 lei -

Preț: 112.64 lei

Preț: 112.64 lei -

Preț: 110.96 lei

Preț: 110.96 lei -

Preț: 128.86 lei

Preț: 128.86 lei -

Preț: 124.72 lei

Preț: 124.72 lei -

Preț: 128.86 lei

Preț: 128.86 lei -

Preț: 122.76 lei

Preț: 122.76 lei -

Preț: 122.64 lei

Preț: 122.64 lei -

Preț: 133.06 lei

Preț: 133.06 lei -

Preț: 132.06 lei

Preț: 132.06 lei -

Preț: 109.73 lei

Preț: 109.73 lei -

Preț: 93.82 lei

Preț: 93.82 lei -

Preț: 101.06 lei

Preț: 101.06 lei -

Preț: 85.08 lei

Preț: 85.08 lei -

Preț: 85.13 lei

Preț: 85.13 lei -

Preț: 79.16 lei

Preț: 79.16 lei -

Preț: 88.39 lei

Preț: 88.39 lei -

Preț: 99.83 lei

Preț: 99.83 lei -

Preț: 92.83 lei

Preț: 92.83 lei -

Preț: 87.43 lei

Preț: 87.43 lei

Preț: 111.17 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 167

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.27€ • 22.33$ • 17.66£

21.27€ • 22.33$ • 17.66£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 20 martie-03 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345426604

ISBN-10: 0345426606

Pagini: 272

Dimensiuni: 131 x 216 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.33 kg

Ediția:Trade Paperback.

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

Seria Ballantine Reader's Circle

ISBN-10: 0345426606

Pagini: 272

Dimensiuni: 131 x 216 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.33 kg

Ediția:Trade Paperback.

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

Seria Ballantine Reader's Circle

Notă biografică

Carolyn See is the author of nine books. She is the Friday-morning reviewer for The Washington Post, and she has been on the boards of the National Book Critics Circle and PEN/West International. She has won both Guggenheim and Getty fellowships and currently teaches English at UCLA. She lives in Pacific Palisades, California.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

IN MAY OF 1996 I FLEW FROM LOS ANGELES TO PARIS, to get settled in the city before I enrolled in the fall semester of the École des Beaux-Arts. I was twenty-eight years old; I had a bachelor's degree in Fine Arts from UCLA and ten thousand dollars in traveler's checks. I'd spent one summer in Paris before, when I was eighteen. I'd been out of school for five years, "finding myself"--thinking I might be an artist--but that search had turned up nothing. In Paris, at least, I had the idea that I could see what others had done, and what I might do. I was scared shitless.

My plane landed at Orly at quarter of six on a cold Tuesday morning. I had a long wait for my luggage, since I'd brought enough in theory to live for a year, and I had a hard and embarrassing discussion with a cab driver when I finally got out of the airport. I'd expected to feel great, but the jet lag--maybe--kept me from being happy as the taxi drove through suburbs and grimy fog. I had to keep reminding myself that a lot of other artists had come to this city. All of them must have had a first day, and that day had to have been lonesome.

I kept waiting for the city to turn into something beautiful, but I had a fair wait. After about forty minutes, we came in sight of the river, and yes, everything was as great as everyone said. I gave the driver the address of the Hôtel du Danube on the rue Jacob, on the Left Bank. It was too expensive for me but I'd allowed myself a week there, since it was close to the École, the Musée d'Orsay, the Louvre, and Saint-Germain-des-Prés, the oldest church in Paris. I think I would have to say that everything in me at that time pointed in one direction, to find out what it meant to be a fine artist, to put my life on the line for art, to combine everything I'd learned and everything I felt and then distill that into paintings. It hadn't happened in LA--"the art scene" in LA was crap-but if it were going to happen anywhere, it would happen here. In two years I'd be thirty, and then the whole thing would be ridiculous.

The cab pulled up to the Hôtel du Danube at ten in the morning, and right away I saw I'd made a mistake. The lobby was dark and glossy and touristy, and a clerk my age gave me a chickenshit stare. I asked for their smallest room and I got it-a dark little cubicle toward the back with a single bed, a shorted-out television, an armoire set at an angle on the sloping floor, and wallpaper that went on all the way across the ceiling-brown cabbage roses on a tan background. The one small window looked out on a roof made of corrugated tin.

I felt lousy, but, again, I put that down to jet lag.

After I washed my hands and face I went out for a walk. I knew a run would make me feel better, but I thought I should know where I was running before I suited up and started.

I walked along the rue Jacob to the rue des Saints-Pères and turned up toward the Seine. The sun was out by now. Things looked the way I expected, but not the way I expected. The river was amazing. I could look across it to the Louvre and that was amazing too, more than I could register, more than I could take in. That so many people, so long ago, had been so dedicated to beauty! I thought of LA, weeds sprouting from the sidewalks and retaining walls bulging with dirt from the last earthquake and all the stucco bungalows on the sides of all the hills and how they faded into that beige background of dead ryegrass. I thought of Salvadorean women on Western Avenue with little kids in strollers and more kids strapped to their backs. Everything I remembered seemed monochromatic and sad.

I came back from the river, walking in the direction of the hotel. I thought I should see Saint-Germain-des-Prés, and the famous cafés on the boulevard Saint-Germain. I was getting hungry. Take it a step at a time, I thought. A thousand people, a thousand thousand people have done what you're doing. They got through it. So you can get through it. Half the people around me were French, but most of the other half were American-hunched together on sidewalks, poring over guidebooks and maps. The French pushed past them. The shops had windows filled with high-class tourist junk-etchings cut out of books and framed, tarnished jewelry you could pick up in LA in thrift shops for ten bucks. And stuff only a moron might want-life-sized stuffed leather pigs.

Saint-Germain-des-Prés was great. Old, old, a mass going on at the far end, groups of Parisians and tourists wandering around in the dark. It calmed me down. I was facing a depressing fact, the fact that I didn't want to go into a place by myself for lunch. I had to remind myself that I was an American, well educated, able-bodied, with enough money to last a while. Picasso had done it (not that he was American). Hemingway could do it. (But thinking of myself at the Ritz Bar in a trench coat might have made me laugh, if I could laugh.)

My plane landed at Orly at quarter of six on a cold Tuesday morning. I had a long wait for my luggage, since I'd brought enough in theory to live for a year, and I had a hard and embarrassing discussion with a cab driver when I finally got out of the airport. I'd expected to feel great, but the jet lag--maybe--kept me from being happy as the taxi drove through suburbs and grimy fog. I had to keep reminding myself that a lot of other artists had come to this city. All of them must have had a first day, and that day had to have been lonesome.

I kept waiting for the city to turn into something beautiful, but I had a fair wait. After about forty minutes, we came in sight of the river, and yes, everything was as great as everyone said. I gave the driver the address of the Hôtel du Danube on the rue Jacob, on the Left Bank. It was too expensive for me but I'd allowed myself a week there, since it was close to the École, the Musée d'Orsay, the Louvre, and Saint-Germain-des-Prés, the oldest church in Paris. I think I would have to say that everything in me at that time pointed in one direction, to find out what it meant to be a fine artist, to put my life on the line for art, to combine everything I'd learned and everything I felt and then distill that into paintings. It hadn't happened in LA--"the art scene" in LA was crap-but if it were going to happen anywhere, it would happen here. In two years I'd be thirty, and then the whole thing would be ridiculous.

The cab pulled up to the Hôtel du Danube at ten in the morning, and right away I saw I'd made a mistake. The lobby was dark and glossy and touristy, and a clerk my age gave me a chickenshit stare. I asked for their smallest room and I got it-a dark little cubicle toward the back with a single bed, a shorted-out television, an armoire set at an angle on the sloping floor, and wallpaper that went on all the way across the ceiling-brown cabbage roses on a tan background. The one small window looked out on a roof made of corrugated tin.

I felt lousy, but, again, I put that down to jet lag.

After I washed my hands and face I went out for a walk. I knew a run would make me feel better, but I thought I should know where I was running before I suited up and started.

I walked along the rue Jacob to the rue des Saints-Pères and turned up toward the Seine. The sun was out by now. Things looked the way I expected, but not the way I expected. The river was amazing. I could look across it to the Louvre and that was amazing too, more than I could register, more than I could take in. That so many people, so long ago, had been so dedicated to beauty! I thought of LA, weeds sprouting from the sidewalks and retaining walls bulging with dirt from the last earthquake and all the stucco bungalows on the sides of all the hills and how they faded into that beige background of dead ryegrass. I thought of Salvadorean women on Western Avenue with little kids in strollers and more kids strapped to their backs. Everything I remembered seemed monochromatic and sad.

I came back from the river, walking in the direction of the hotel. I thought I should see Saint-Germain-des-Prés, and the famous cafés on the boulevard Saint-Germain. I was getting hungry. Take it a step at a time, I thought. A thousand people, a thousand thousand people have done what you're doing. They got through it. So you can get through it. Half the people around me were French, but most of the other half were American-hunched together on sidewalks, poring over guidebooks and maps. The French pushed past them. The shops had windows filled with high-class tourist junk-etchings cut out of books and framed, tarnished jewelry you could pick up in LA in thrift shops for ten bucks. And stuff only a moron might want-life-sized stuffed leather pigs.

Saint-Germain-des-Prés was great. Old, old, a mass going on at the far end, groups of Parisians and tourists wandering around in the dark. It calmed me down. I was facing a depressing fact, the fact that I didn't want to go into a place by myself for lunch. I had to remind myself that I was an American, well educated, able-bodied, with enough money to last a while. Picasso had done it (not that he was American). Hemingway could do it. (But thinking of myself at the Ritz Bar in a trench coat might have made me laugh, if I could laugh.)

Recenzii

"The Handyman proves once again that Carolyn See is one of this generation's most talented and versatile writers."

--FANNIE FLAGG

"IRRESISTIBLE . . . A SPARKLING ENTERTAINMENT."

--Entertainment Weekly

"BEGUILING, CHARMING, WITTY, INSPIRING--Carolyn See's novel The Handyman is so wonderful in so many ways that it's going to seem as if her mother wrote every review for it. Twenty-eight-year-old Bob Hampton is a struggling artist who is panicking at the possibility that he will never find his authentic 'voice.' After a failed (and endearing) trip to Paris, Bob returns to his home in Los Angeles and decides to spend the summer working as a handyman before giving art school one more try. What he becomes, of course, is a handyman of the heart."

--The Cleveland Plain Dealer

"[AN] INVENTIVE AND ENERGETIC STORY . . . See offers a satisfying take on the mysterious and unpredictable ways that real life can be turned into art."

--People

--FANNIE FLAGG

"IRRESISTIBLE . . . A SPARKLING ENTERTAINMENT."

--Entertainment Weekly

"BEGUILING, CHARMING, WITTY, INSPIRING--Carolyn See's novel The Handyman is so wonderful in so many ways that it's going to seem as if her mother wrote every review for it. Twenty-eight-year-old Bob Hampton is a struggling artist who is panicking at the possibility that he will never find his authentic 'voice.' After a failed (and endearing) trip to Paris, Bob returns to his home in Los Angeles and decides to spend the summer working as a handyman before giving art school one more try. What he becomes, of course, is a handyman of the heart."

--The Cleveland Plain Dealer

"[AN] INVENTIVE AND ENERGETIC STORY . . . See offers a satisfying take on the mysterious and unpredictable ways that real life can be turned into art."

--People

Descriere

Bob Hampton, an aspiring painter, abandons his dreams to earn a living as a handyman. Although he's not a great fixer, he ends up being a celebrated, provocative artist because of his knack for fixing the lives of the people around him.