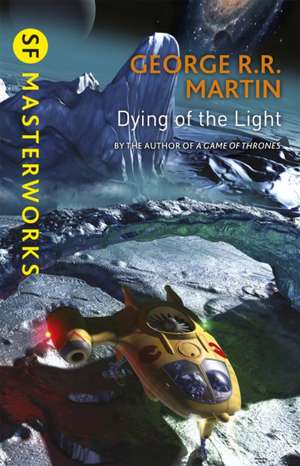

Dying Of The Light: S.F. Masterworks

Autor George R. R. Martinen Limba Engleză Paperback – 10 sep 2015

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 49.11 lei 22-36 zile | +25.39 lei 6-12 zile |

| Orion Publishing Group – 10 sep 2015 | 49.11 lei 22-36 zile | +25.39 lei 6-12 zile |

| Bantam Books – 31 aug 2004 | 98.78 lei 43-57 zile |

Din seria S.F. Masterworks

- 23%

Preț: 53.68 lei

Preț: 53.68 lei -

Preț: 63.74 lei

Preț: 63.74 lei - 24%

Preț: 48.13 lei

Preț: 48.13 lei - 22%

Preț: 65.60 lei

Preț: 65.60 lei - 24%

Preț: 43.34 lei

Preț: 43.34 lei - 24%

Preț: 43.59 lei

Preț: 43.59 lei - 23%

Preț: 48.88 lei

Preț: 48.88 lei - 20%

Preț: 69.39 lei

Preț: 69.39 lei - 24%

Preț: 53.53 lei

Preț: 53.53 lei - 24%

Preț: 48.31 lei

Preț: 48.31 lei - 25%

Preț: 42.74 lei

Preț: 42.74 lei - 23%

Preț: 48.94 lei

Preț: 48.94 lei - 25%

Preț: 42.14 lei

Preț: 42.14 lei - 23%

Preț: 53.66 lei

Preț: 53.66 lei - 24%

Preț: 48.57 lei

Preț: 48.57 lei - 21%

Preț: 66.43 lei

Preț: 66.43 lei -

Preț: 64.05 lei

Preț: 64.05 lei - 23%

Preț: 49.19 lei

Preț: 49.19 lei - 23%

Preț: 48.86 lei

Preț: 48.86 lei - 24%

Preț: 48.23 lei

Preț: 48.23 lei - 21%

Preț: 67.73 lei

Preț: 67.73 lei - 23%

Preț: 54.24 lei

Preț: 54.24 lei - 24%

Preț: 48.48 lei

Preț: 48.48 lei - 23%

Preț: 48.81 lei

Preț: 48.81 lei - 24%

Preț: 47.69 lei

Preț: 47.69 lei - 23%

Preț: 43.93 lei

Preț: 43.93 lei - 22%

Preț: 55.16 lei

Preț: 55.16 lei - 24%

Preț: 47.75 lei

Preț: 47.75 lei - 23%

Preț: 48.85 lei

Preț: 48.85 lei - 24%

Preț: 48.07 lei

Preț: 48.07 lei - 22%

Preț: 49.98 lei

Preț: 49.98 lei - 24%

Preț: 48.29 lei

Preț: 48.29 lei - 24%

Preț: 47.94 lei

Preț: 47.94 lei - 23%

Preț: 48.86 lei

Preț: 48.86 lei - 23%

Preț: 49.33 lei

Preț: 49.33 lei - 23%

Preț: 53.78 lei

Preț: 53.78 lei - 24%

Preț: 53.14 lei

Preț: 53.14 lei - 24%

Preț: 48.70 lei

Preț: 48.70 lei - 23%

Preț: 54.00 lei

Preț: 54.00 lei - 24%

Preț: 52.58 lei

Preț: 52.58 lei - 24%

Preț: 43.33 lei

Preț: 43.33 lei - 24%

Preț: 48.25 lei

Preț: 48.25 lei - 22%

Preț: 65.30 lei

Preț: 65.30 lei - 23%

Preț: 48.78 lei

Preț: 48.78 lei - 24%

Preț: 48.07 lei

Preț: 48.07 lei - 25%

Preț: 42.74 lei

Preț: 42.74 lei - 24%

Preț: 48.15 lei

Preț: 48.15 lei - 24%

Preț: 48.45 lei

Preț: 48.45 lei - 24%

Preț: 47.93 lei

Preț: 47.93 lei - 23%

Preț: 48.78 lei

Preț: 48.78 lei

Preț: 49.11 lei

Preț vechi: 63.91 lei

-23% Nou

Puncte Express: 74

Preț estimativ în valută:

9.40€ • 10.21$ • 7.90£

9.40€ • 10.21$ • 7.90£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 31 martie-14 aprilie

Livrare express 15-21 martie pentru 35.38 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781473212527

ISBN-10: 1473212529

Pagini: 368

Dimensiuni: 133 x 199 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Orion Publishing Group

Seria S.F. Masterworks

ISBN-10: 1473212529

Pagini: 368

Dimensiuni: 133 x 199 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Orion Publishing Group

Seria S.F. Masterworks

Notă biografică

George R.R. Martin published his first story in 1971 and quickly rose to prominence, winning four HUGO and two NEBULA Awards in quick succession before he turned his attention to fantasy with the historical horror novel FEVRE DREAM, now a Fantasy Masterwork. Since then he has won every major award in the fields of fantasy, SF and horror. His magnificent epic saga A Song of Ice and Fire is redefining epic fantasy for a new generation, and is the basis for the hit HBO series GAME OF THRONES. George R.R. Martin lives in New Mexico.

Read more at http://sf-encyclopedia.com/entry/martin_george_r_r

Read more at http://sf-encyclopedia.com/entry/martin_george_r_r

Descriere

A stunning space adventure from the bestselling author of A GAME OF THRONES.

Extras

Chapter One

beyond the window, water slapped against the pilings of the wooden sidewalk along the canal. Dirk t’Larien looked up and saw a low black barge drift slowly past in the moonlight. A solitary figure stood at the stern, leaning on a thin dark pole. Everything was etched quite clearly, for Braque’s moon was riding overhead, big as a fist and very bright.

Behind it was a stillness and a smoky darkness, an unmoving curtain that hid the farther stars. A cloud of dust and gas, he thought. The Tempter’s Veil.

The beginning came long after the end: a whisperjewel.

It was wrapped in layers of silver foil and soft dark velvet, just as he had given it to her years before. He undid its package that night, sitting by the window of his room that overlooked the wide scummy canal where merchants poled fruit barges endlessly up and down. The gem was just as Dirk recalled it: a deep red, laced with thin black lines, shaped like a tear. He remembered the day the esper had cut it for them, back on Avalon.

After a long time he touched it.

It was smooth and very cold against the tip of his finger, and deep within his brain it whispered. Memories and promises that he had not forgotten.

He was here on Braque for no particular reason, and he never knew how they found him. But they did, and Dirk t’Larien got his jewel back.

“Gwen,” he said quietly, all to himself, just to shape the word again and feel the familiar warmth on his tongue. His Jenny, his Guinevere, mistress of abandoned dreams.

It had been seven standard years, he thought, while his finger stroked the cold, cold jewel. But it felt like seven lifetimes. And everything was over. What could she want of him now? The man who had loved her, that other Dirk t’Larien, that maker-of-promises and giver-of-jewels, was a dead man.

Dirk lifted his hand to brush a spray of gray-brown hair back out of his eyes. And suddenly, not meaning to, he remembered how Gwen would brush his hair away whenever she meant to kiss him.

He felt very tired then, and very lost. His carefully nurtured cynicism trembled, and a weight fell upon his shoulders, a ghost weight, the heaviness of the person he had been once and no longer was. He had indeed changed over the years, and he had called it growing wise, but now all that wisdom abruptly seemed to sour. His wandering thoughts lingered on all the promises he had broken, the dreams he had postponed and then mislaid, the ideals compromised, the shining future lost to tedium and rot.

Why did she make him remember? Too much time had passed, too much had happened to him—probably to both of them. Besides, he had never really meant for her to use the whisperjewel. It had been a stupid gesture, the adolescent posturing of a young romantic. No reasonable adult would hold him to such an absurd pledge. He could not go, of course. He had hardly had time to see Braque yet, he had his own life, he had important things to do. After all this time, Gwen could not possibly expect him to ship off to the outworlds.

Resentful, he reached out and took the jewel in his palm, and his fist closed hard around the smallness of it. He would toss it through the window, he decided, out into the dark waters of the canal, out and away with everything that it meant. But once within his fist, the gem was an ice inferno, and the memories were knives.

. . . because she needs you, the jewel whispered. Because you promised.

His hand did not move. His fist stayed closed. The cold against his palm passed beyond pain, into numbness.

That other Dirk, the younger one, Gwen’s Dirk. He had promised. But so had she, he remembered. Long ago on Avalon. The old esper, a wizened Emereli with a very minor Talent and red-gold hair, had cut two jewels. He had read Dirk t’Larien, had felt all the love Dirk had for his Jenny, and then had put as much of that into the gem as his poor psionic powers allowed him to. Later, he had done the same for Gwen. Then they had traded jewels.

It had been his idea. It may not always be so, he had told her, quoting an ancient poem. So they had promised, both of them: Send this memory, and I will come. No matter where I am, or when, or what has passed between us. I will come, and there will be no questions.

But it was a shattered promise. Six months after she had left him, Dirk had sent her the jewel. She had not come. After that, he could never have expected her to invoke his promise. Yet now she had.

Did she really expect him to come?

And he knew, with sadness, that the man he had been back then, that man would come to her, no matter what, no matter how much he might hate her—or love her. But that fool was long buried. Time and Gwen had killed him.

But he still listened to the jewel and felt his old feelings and his new weariness. And finally he looked up and thought, Well, perhaps it is not too late after all.

There are many ways to move between the stars, and some of them are faster than light and some are not, and all of them are slow. It takes most of a man’s lifetime to ship from one end of the manrealm to the other, and the manrealm—the scattered worlds of humanity and the greater emptiness in between—is the very smallest part of the galaxy. But Braque was close to the Veil, and the outworlds beyond, and there was some trade back and forth, so Dirk could find a ship.

It was named the Shuddering of Forgotten Enemies, and it went from Braque to Tara and then through the Veil to Wolfheim and then to Kimdiss and finally to Worlorn, and the voyage, even by FTL drive, took more than three months standard. After Worlorn, Dirk knew, the Shuddering would move on, to High Kavalaan and ai-Emerel and the Last Stars, before it turned and began to retrace its tedious route.

The spacefield had been built to handle twenty ships a day; now it handled perhaps one a month. The greater part of it was shut, dark, abandoned. The Shuddering set down in the middle of a small portion that still functioned, dwarfing a nearby cluster of private ships and a partially dismantled Toberian freighter.

A section of the vast terminal, automated and yet lifeless, was still brightly lit, but Dirk moved through it quickly, out into the night, an empty outworld night that cried for want of stars. They were there, wait- ing for him, just beyond the main doors, more or less as he had expected. The captain of the Shuddering had lasered on ahead as soon as the ship emerged from drive into normal space.

Gwen Delvano had come to meet him, then, as he had asked her to. But she had not come alone. Gwen and the man she had brought with her were talking to each other in low, careful voices when he emerged from the terminal.

Dirk stopped just past the door, smiled as easily as he could manage, and dropped the single light bag he carried: “Hey,” he said softly. “I hear there’s a Festival going on.”

She had turned at the sound of his voice, and now she laughed, a so-well-remembered laugh. “No,” she said. “You’re about ten years too late.”

Dirk scowled and shook his head. “Hell,” he said. Then he smiled again, and she came to him, and they embraced. The other man, the stranger, stood and watched without a trace of self-consciousness.

It was a short hug. No sooner had Dirk wrapped his arms about her than Gwen pulled back. After the break they stood very close, and each looked to see what the years had done.

She was older but much the same, and what changes he saw were probably only defects in his memory. Her wide green eyes were not quite as wide or green as he remembered them, and she was a little taller than he recalled and perhaps a bit heavier. But she was close enough; she smiled the same way, and her hair was the same; fine and dark, falling past her shoulders in a shimmering stream blacker than an outworld night. She wore a white turtleneck pullover and belted pants of sturdy chameleon cloth, faded to night-black now, and a thick headband, as she had liked to dress on Avalon. Now she wore a bracelet too, and that was new. Or perhaps the proper word was armlet. It was a massive thing, cool silver set with jade, that covered half her left forearm. The sleeve of her pullover was rolled back to display it.

“You’re thinner, Dirk,” she said.

He shrugged and thrust his hands into his jacket pockets. “Yes,” he said. In truth, he was almost gaunt, though still a little round-shouldered from slouching too much. The years had aged him in other ways as well; now his hair had more gray than brown, when once it had been the other way around, and he wore it nearly as long as Gwen, though his was a mass of curls and tangles.

“A long time,” Gwen said.

“Seven years, standard,” he replied nodding. “I didn’t think that . . .”

The other man, the waiting stranger, coughed then, as if to remind them that they were not alone. Dirk glanced up, and Gwen turned. The man came forward and bowed politely. Short and chubby and very blond—his hair looked almost white—he wore a brightly colored silkeen suit, all green and yellow, and a tiny black knit cap that stayed in place despite his bow.

“Arkin Ruark,” he said to Dirk.

“Dirk t’Larien.”

“Arkin is working with me on the project,” Gwen said.

“Project?”

She blinked. “Don’t you even know why I’m here?”

He didn’t. The whisperjewel had been sent from Worlorn, so he had known not much else than where to find her. “You’re an ecologist,” he said. “On Avalon . . .”

“Yes. At the Institute. A long time ago. I finished there, got my credentials, and I’ve been on High Kavalaan since. Until I was sent here.”

“Gwen is with the Ironjade Gathering,” Ruark said. He had a small, tight smile on his face. “Me, I’m representing Impril City Academy. Kimdiss. You know?”

Dirk nodded. Ruark was a Kimdissi then, an outworlder, from one of their universities.

“Impril and Ironjade, well, after the same thing, you know? Research on ecological interaction on Worlorn. Never really done properly during the Festival, the outworlds not being so strong on ecology, none of them. A science ai-forgotten, as the Emereli say. But that’s the project. Gwen and I knew each other from before, so we thought, well, here for the same reason, so it is good sense to work together and learn what we can learn.”

“I suppose,” Dirk said. He was not really overly interested in the project just then. He wanted to talk to Gwen. He looked at her. “You’ll have to tell me all about it later. When we talk. I imagine you want to talk.”

She gave him an odd look. “Yes, of course. We do have a lot to talk about.”

He picked up his bag. “Where to?” he asked. “I could probably do with a bath and some food.”

Gwen exchanged glances with Ruark. “Arkin and I were just talking about that. He can put you up. We’re in the same building. Only a few floors apart.”

Ruark nodded. “Gladly, gladly. Pleasure in doing for friends, and both of us are friend to Gwen, are we not?”

“Uh,” said Dirk. “I thought, somehow, that I would stay with you, Gwen.”

She could not look at him for a time. She looked at Ruark, at the ground, at the black night sky, before her eyes finally found his. “Perhaps,” she said, not smiling now, her voice careful. “But not right now. I don’t think it would be best, not immediately. But we’ll go home, of course. We have a car.”

“This way,” Ruark put in, before Dirk could frame his words. Something was very strange. He had played through the reunion scene a hundred times on board the Shuddering during the months of his voyage, and sometimes he had imagined it tender and loving, and sometimes it had been an angry confrontation, and often it had been tearful—but it had never been quite like this, awkward and at odd angles, with a stranger present throughout it all. He began to wonder exactly who Arkin Ruark was, and whether his relationship with Gwen was quite what they said it was. But then, they had hardly said anything. Without knowing what to say or to think, he shrugged and followed as they led him to their aircar.

The walk was quite short. The car, when they reached it, took Dirk aback. He had seen a lot of different types of aircars in his travels, but none quite like this one; huge and steel-gray, with curved and muscled triangular wings, it looked almost alive, like a great aerial manta ray fashioned in metal. A small cockpit with four seats was set between the wings, and beneath the wingtips he glimpsed ominous rods.

He looked at Gwen and pointed. “Are those lasers?”

She nodded, smiling just a little.

“What the hell are you flying?” Dirk asked. “It looks like a war machine. Are we going to be assaulted by Hrangans? I haven’t seen anything like that since we toured the Institute museums back on Avalon.”

Gwen laughed, took his bag from him, and tossed it into the back seat. “Get in,” she told him. “It is a perfectly fine aircar of High Kavalaan manufacture. They’ve only recently started turning out their own. It’s supposed to look like an animal, the black banshee. A flying predator, also the brother-beast of the Ironjade Gathering. Very big in their folklore, sort of a totem.”

She climbed in, behind the stick, and Ruark followed a bit awkwardly, vaulting over the armored wing into the back. Dirk did not move. “But it has lasers!” he insisted.

Gwen sighed. “They’re not charged, and never have been. Every car built on High Kavalaan has weapons of some sort. The culture demands it. And I don’t mean just Ironjade’s. Redsteel, Braith, and the Shanagate Holding are all the same.”

Dirk walked around the car and climbed in next to Gwen, but his face was blank. “What?”

“Those are the four Kavalar holdfast-coalitions,” she explained. “Think of them as small nations, or big families. They’re a little of both.”

“But why the lasers?”

“High Kavalaan is a violent planet,” Gwen replied.

Ruark gave a snort of laughter. “Ah, Gwen,” he said. “That is utter wrong, utter!”

“Wrong?” she snapped.

“Very,” Ruark said. “Yes, utter, because you are close to truth, half and not everything, worst lie of all.”

Dirk turned in his seat to look back at the chubby blond Kimdissi. “What?”

“High Kavalaan was a violent planet, truth. But now, truth is, the violence is the Kavalars. Hostile folk, each and every among them, xenophobes often, racists. Proud and jealous. With their highwars and their code duello, yes, and that is why Kavalar cars have guns. To fight with, in the air! I warn you, t’Larien—”

“Arkin!” Gwen said between her teeth, and Dirk started at the edged malice in her tone. She threw on the gravity grid suddenly, touched the stick, and the aircar wrenched forward and left the ground with a whine of protest, rising rapidly. The port below them was bright with light where the Shuddering of Forgotten Enemies stood among the lesser starships, shadowy everywhere else. Around it was darkness to the unseen horizon where black ground blended with blacker sky. Only a thin powder of stars lit the night above. This was the Fringe, with intergalactic space above and the dusky curtain of the Tempter’s Veil below, and the world seemed lonelier than Dirk had ever imagined.

Ruark had subsided, muttering, and a heavy silence lay over the car for a long moment.

“Arkin is from Kimdiss,” Gwen said finally, and she forced a chuckle. Dirk remembered her too well to be fooled, however; she was not one bit less tense than when she had snapped at Ruark a moment before.

“I don’t understand,” Dirk said, feeling quite stupid, since everyone seemed to think he should.

“You are no outworlder,” Ruark said. “Avalon, Baldur, whatever world, it doesn’t matter. Your people inside the Veil don’t know Kavalars.”

“Or Kimdissi,” Gwen said, a little more calmly.

Ruark grunted. “A sarcasm,” he told Dirk. “Kimdissi and Kavalars, well, we don’t get on, you know? So Gwen is telling you I’m all prejudiced and not to believe me.”

“Yes, Arkin,” she said. “Dirk, he doesn’t know High Kavalaan, doesn’t understand the culture or the people. Like all Kimdissi, he’ll tell you only the worst, but everything is more complex than he would credit. So remember that when this glib scoundrel starts working on you. It should be easy. In the old days, you were always telling me that every question has thirty sides.”

Dirk laughed. “Fair enough,” he said, “and true. Although these last few years I’ve begun to think that thirty is a bit low. I still don’t understand what this is all about, however. Take the car—does it come with your job? Or do you have to fly something like this just because you work for the Ironjade Gathering?”

“Ah,” Ruark said loudly. “You do not work for the Ironjade Gathering, Dirk. No, you are of them, you are not—two choices only. You are not of Ironjade, you do not work for Ironjade!”

“Yes,” said Gwen, the edge returning to her voice. “And I am of Ironjade. I wish you’d remember that, Arkin. Sometimes you begin to annoy me.”

“Gwen, Gwen,” Ruark said, sounding very flustered. “You are a friend, a soulmate, very. We have tussled great problems, us two. I would never offend, do not mean to. You are not a Kavalar though, never. For one, you are too much a woman, a true woman, not merely an eyn-kethi nor a betheyn.”

“No? I’m not? I wear the bond of jade-and-silver, though.” She glanced toward Dirk and lowered her voice. “For Jaan,” she said. “This is really his car, and that’s why I fly it, to answer your original question. For Jaan.”

Silence. The wind was the only noise, moving around them as they fell upward into blackness, tossing Gwen’s long straight hair and Dirk’s tangles. It knifed right through his thin Braqui clothing. He wondered briefly why the aircar had no bubble canopy, only a thin windscreen that was hardly any use at all. Then he folded his arms tight against his chest, and slid down into the seat. “Jaan?” he asked quietly. A question. The answer would come, he knew, and he dreaded it, just from the way that Gwen had spoken the name, with a sort of strange defiance.

“He doesn’t know,” Ruark said.

Gwen sighed, and Dirk could see her tense. “I’m sorry, Dirk. I thought you would know. It has been a long time. I thought, well, one of the people we both knew back on Avalon, one of them surely has told you.”

“I never see anyone anymore,” Dirk said carefully. “That we knew, together. You know. I travel a lot. Braque, Prometheus, Jamison’s World.” His voice rang hollow and inane in his ears. He paused and swallowed. “Who is Jaan?”

“Jaantony Riv Wolf high-Ironjade Vikary,” Ruark said.

“Jaan is my . . .” She hesitated. “It is not easy to explain. I am betheyn to Jaan, cro-betheyn to his teyn Garse.” She looked over, a brief glance away from the aircar instruments, then back again. There was no comprehension on Dirk’s face.

“Husband,” she said then, shrugging. “I’m sorry, Dirk. That’s not quite right, but it is the closest I can come in a single word. Jaan is my husband.”

Dirk, huddled low in his seat with his arms folded, said nothing. He was cold, and he hurt, and he wondered why he was there. He remembered the whisperjewel, and he still wondered. She had some reason for sending for him, surely, and in time she would tell him. And really, he could hardly have expected that she would be alone. At the port he had even thought, quite briefly, that perhaps Ruark . . . and that hadn’t bothered him.

When he had been silent for too long, Gwen looked over once again. “I’m sorry,” she repeated. “Dirk. Really. You should never have come.”

And he thought, She’s right.

The three of them flew on without speaking. Words had been said, and not the words that Dirk had wanted, but words that had changed nothing. He was here on Worlorn, and Gwen was still beside him, though suddenly a stranger. They were both strangers. He sat slumped in his seat, alone with his thoughts, while a cold wind stroked his face.

On Braque, somehow, he had thought that the whisperjewel meant she was calling him back, that she wanted him again. The only question that concerned him was whether he would go, whether he could return to her, whether Dirk t’Larien still could love and be loved. That had not been it at all, he knew now.

Send this memory, and I will come, and there will be no questions. That was the promise, the only promise. Nothing more.

He became angry. Why was she doing this to him? She had held the jewel and felt his feelings. She could have guessed. No need of hers could be worth the price of this remembering.

Then, finally, calm came back to Dirk t’Larien. With his eyes tight shut, he could see the canal on Braque again, and the lone black barge that had seemed so briefly important. And he remembered his resolve, to try again, to be as he had been, to come to her and give whatever he could give, whatever she might need—for himself, as well as for her.

He straightened with an effort, unfolded his arms, opened his eyes, and sat up into the biting wind. Then, deliberately, he looked at Gwen and smiled his old shy smile for her. “Ah, Jenny,” he said, “I’m sorry too. But it doesn’t matter. I didn’t know, but that doesn’t matter. I’m glad I came, and you should be glad too. Seven years is too long, right?”

She glanced at him, then back at her instruments, and licked her lips nervously. “Yes. Seven years is too long, Dirk.”

“Will I meet Jaan?”

She nodded. “And Garse too, his teyn.”

Below, somewhere, he heard water, a river lost in the darkness. It was gone quickly; they were moving quite fast. Dirk peered over the side of the aircar, down past the wings into the rushing black, then up. “You need more stars,” he said thoughtfully. “I feel as though I’m going blind.”

“I know what you mean,” Gwen said. She smiled, and quite suddenly Dirk felt better than he had for a long time.

“Remember the sky on Avalon?” he asked.

“Yes. Of course.”

“Lots of stars there. It was a beautiful world.”

“Worlorn has a beauty too,” she said. “How much do you know of it?”

“A little,” Dirk replied, still looking at her. “I know about the Festival, and that the planet is a rogue, and not much else. A woman on the ship told me that Tomo and Walberg discovered the place on their jaunt to the end of the galaxy.”

“Not quite,” said Gwen. “But the story has a certain charm to it. Anyway, everything you’ll see is part of the Festival. The whole planet is. All the worlds of the Fringe took part, and the culture of each is reflected here in one of the cities. There are fourteen cities, for the fourteen worlds of the Fringe. In between you’ve got the spacefield and the Common, which is sort of a park. We’re flying over it now. The Common is not very interesting, even by day. They had fairs and games there in the years of the Festival.”

“Where is your project?”

“The wilderness,” Ruark said. “Beyond the cities, beyond the mountainwall.”

Gwen said, “Look.”

Dirk looked. At the horizon he could vaguely make out a row of mountains, a jagged black barrier that climbed out of the Common to eclipse the lower stars. A spark of bloody light sat high upon one peak, and it grew as they drew near. Taller and higher it became, though not more brilliant; the color stayed a murky, threatening red that reminded Dirk somehow of the whisperjewel.

“Home,” Gwen announced as the light swelled. “The city Larteyn. Lar is Old Kavalar for sky. This is the city of High Kavalaan. Some people call it the Firefort.”

He could see why at a glance. Built into the shoulder of the mountain, rock beneath it and rock to its back, the Kavalar city was also a fortress—square and thick, massively walled, with narrow slit windows. Even the towers that rose behind the city walls were heavy and solid. And short; the Mountain loomed above them, its dark stone stained bloody by reflected light. But the lights of the city itself were not reflected; the walls and streets of Larteyn burned with a dull glowering fire of their own.

“Glowstone,” Gwen told him in answer to his unvoiced question. “It absorbs light during the day and gives it back at night. On High Kavalaan, it was used mostly for jewelry, but they quarried it by the ton and shipped it off to Worlorn for the Festival.”

“Baroque impressive,” Ruark said. “Kavalar impressive.” Dirk only nodded.

“You should have seen it in the old days,” Gwen said. “Larteyn drank from the seven suns by day and lit the range by night. Like a dagger of fire. The stones are fading now—the Wheel grows more distant every hour. In another decade the city will go dark as a burnt-out ember.”

“It doesn’t look very big,” Dirk said. “How many people did it hold?”

“A million, once. You’re just seeing the tip of the iceberg. The city is built into the mountain.”

“Very Kavalar,” Ruark said. “A deep holding, a fastness in stone. But empty now. Twenty people, last count, us including.”

The aircar passed over the outer wall, set flush to the cliff on the edge of the wide mountain ledge, to make one long straight drop past rock and glowstone. Below them Dirk saw wide walkways, and rows of slowly stirring pennants, and great carved gargoyles with burning glowstone eyes. The buildings were white stone and ebon wood, and on their flanks the rock fires were reflected in long red streaks, like open wounds on some hulking dark beast. They flew over towers and domes and streets, twisting alleys and wide boulevards, open courtyards and a huge many-tiered outdoor theater.

Empty, all empty. Not a figure moved in the red-drenched ways of Larteyn.

Gwen spiraled down to the roof of a square black tower. As she hovered and slowly faded the gravity grid to bring them in, Dirk noted two other cars in the airlot beneath them: a sleek yellow teardrop and a formidable old military flyer with the look of century-old war surplus. It was olive-green, square and sheathed in armor, with lasercannon on the forward hood and pulse-tubes on the rear.

She put their metal manta down between the two cars, and they vaulted out onto the roof. When they reached the bank of elevators, Gwen turned to face him, her face flushed and strange in the brooding reddish light. “It is late,” she said. “We had all better rest.”

Dirk did not question the dismissal. “Jaan?” he said.

“You’ll meet him tomorrow,” she replied. “I need a chance to talk to him first.”

“Why?” he asked, but Gwen had already turned and started toward the stairs. Then the tube arrived and Ruark put a hand on his shoulder and pulled him inside.

They rode downward, to sleep and to dreams.

beyond the window, water slapped against the pilings of the wooden sidewalk along the canal. Dirk t’Larien looked up and saw a low black barge drift slowly past in the moonlight. A solitary figure stood at the stern, leaning on a thin dark pole. Everything was etched quite clearly, for Braque’s moon was riding overhead, big as a fist and very bright.

Behind it was a stillness and a smoky darkness, an unmoving curtain that hid the farther stars. A cloud of dust and gas, he thought. The Tempter’s Veil.

The beginning came long after the end: a whisperjewel.

It was wrapped in layers of silver foil and soft dark velvet, just as he had given it to her years before. He undid its package that night, sitting by the window of his room that overlooked the wide scummy canal where merchants poled fruit barges endlessly up and down. The gem was just as Dirk recalled it: a deep red, laced with thin black lines, shaped like a tear. He remembered the day the esper had cut it for them, back on Avalon.

After a long time he touched it.

It was smooth and very cold against the tip of his finger, and deep within his brain it whispered. Memories and promises that he had not forgotten.

He was here on Braque for no particular reason, and he never knew how they found him. But they did, and Dirk t’Larien got his jewel back.

“Gwen,” he said quietly, all to himself, just to shape the word again and feel the familiar warmth on his tongue. His Jenny, his Guinevere, mistress of abandoned dreams.

It had been seven standard years, he thought, while his finger stroked the cold, cold jewel. But it felt like seven lifetimes. And everything was over. What could she want of him now? The man who had loved her, that other Dirk t’Larien, that maker-of-promises and giver-of-jewels, was a dead man.

Dirk lifted his hand to brush a spray of gray-brown hair back out of his eyes. And suddenly, not meaning to, he remembered how Gwen would brush his hair away whenever she meant to kiss him.

He felt very tired then, and very lost. His carefully nurtured cynicism trembled, and a weight fell upon his shoulders, a ghost weight, the heaviness of the person he had been once and no longer was. He had indeed changed over the years, and he had called it growing wise, but now all that wisdom abruptly seemed to sour. His wandering thoughts lingered on all the promises he had broken, the dreams he had postponed and then mislaid, the ideals compromised, the shining future lost to tedium and rot.

Why did she make him remember? Too much time had passed, too much had happened to him—probably to both of them. Besides, he had never really meant for her to use the whisperjewel. It had been a stupid gesture, the adolescent posturing of a young romantic. No reasonable adult would hold him to such an absurd pledge. He could not go, of course. He had hardly had time to see Braque yet, he had his own life, he had important things to do. After all this time, Gwen could not possibly expect him to ship off to the outworlds.

Resentful, he reached out and took the jewel in his palm, and his fist closed hard around the smallness of it. He would toss it through the window, he decided, out into the dark waters of the canal, out and away with everything that it meant. But once within his fist, the gem was an ice inferno, and the memories were knives.

. . . because she needs you, the jewel whispered. Because you promised.

His hand did not move. His fist stayed closed. The cold against his palm passed beyond pain, into numbness.

That other Dirk, the younger one, Gwen’s Dirk. He had promised. But so had she, he remembered. Long ago on Avalon. The old esper, a wizened Emereli with a very minor Talent and red-gold hair, had cut two jewels. He had read Dirk t’Larien, had felt all the love Dirk had for his Jenny, and then had put as much of that into the gem as his poor psionic powers allowed him to. Later, he had done the same for Gwen. Then they had traded jewels.

It had been his idea. It may not always be so, he had told her, quoting an ancient poem. So they had promised, both of them: Send this memory, and I will come. No matter where I am, or when, or what has passed between us. I will come, and there will be no questions.

But it was a shattered promise. Six months after she had left him, Dirk had sent her the jewel. She had not come. After that, he could never have expected her to invoke his promise. Yet now she had.

Did she really expect him to come?

And he knew, with sadness, that the man he had been back then, that man would come to her, no matter what, no matter how much he might hate her—or love her. But that fool was long buried. Time and Gwen had killed him.

But he still listened to the jewel and felt his old feelings and his new weariness. And finally he looked up and thought, Well, perhaps it is not too late after all.

There are many ways to move between the stars, and some of them are faster than light and some are not, and all of them are slow. It takes most of a man’s lifetime to ship from one end of the manrealm to the other, and the manrealm—the scattered worlds of humanity and the greater emptiness in between—is the very smallest part of the galaxy. But Braque was close to the Veil, and the outworlds beyond, and there was some trade back and forth, so Dirk could find a ship.

It was named the Shuddering of Forgotten Enemies, and it went from Braque to Tara and then through the Veil to Wolfheim and then to Kimdiss and finally to Worlorn, and the voyage, even by FTL drive, took more than three months standard. After Worlorn, Dirk knew, the Shuddering would move on, to High Kavalaan and ai-Emerel and the Last Stars, before it turned and began to retrace its tedious route.

The spacefield had been built to handle twenty ships a day; now it handled perhaps one a month. The greater part of it was shut, dark, abandoned. The Shuddering set down in the middle of a small portion that still functioned, dwarfing a nearby cluster of private ships and a partially dismantled Toberian freighter.

A section of the vast terminal, automated and yet lifeless, was still brightly lit, but Dirk moved through it quickly, out into the night, an empty outworld night that cried for want of stars. They were there, wait- ing for him, just beyond the main doors, more or less as he had expected. The captain of the Shuddering had lasered on ahead as soon as the ship emerged from drive into normal space.

Gwen Delvano had come to meet him, then, as he had asked her to. But she had not come alone. Gwen and the man she had brought with her were talking to each other in low, careful voices when he emerged from the terminal.

Dirk stopped just past the door, smiled as easily as he could manage, and dropped the single light bag he carried: “Hey,” he said softly. “I hear there’s a Festival going on.”

She had turned at the sound of his voice, and now she laughed, a so-well-remembered laugh. “No,” she said. “You’re about ten years too late.”

Dirk scowled and shook his head. “Hell,” he said. Then he smiled again, and she came to him, and they embraced. The other man, the stranger, stood and watched without a trace of self-consciousness.

It was a short hug. No sooner had Dirk wrapped his arms about her than Gwen pulled back. After the break they stood very close, and each looked to see what the years had done.

She was older but much the same, and what changes he saw were probably only defects in his memory. Her wide green eyes were not quite as wide or green as he remembered them, and she was a little taller than he recalled and perhaps a bit heavier. But she was close enough; she smiled the same way, and her hair was the same; fine and dark, falling past her shoulders in a shimmering stream blacker than an outworld night. She wore a white turtleneck pullover and belted pants of sturdy chameleon cloth, faded to night-black now, and a thick headband, as she had liked to dress on Avalon. Now she wore a bracelet too, and that was new. Or perhaps the proper word was armlet. It was a massive thing, cool silver set with jade, that covered half her left forearm. The sleeve of her pullover was rolled back to display it.

“You’re thinner, Dirk,” she said.

He shrugged and thrust his hands into his jacket pockets. “Yes,” he said. In truth, he was almost gaunt, though still a little round-shouldered from slouching too much. The years had aged him in other ways as well; now his hair had more gray than brown, when once it had been the other way around, and he wore it nearly as long as Gwen, though his was a mass of curls and tangles.

“A long time,” Gwen said.

“Seven years, standard,” he replied nodding. “I didn’t think that . . .”

The other man, the waiting stranger, coughed then, as if to remind them that they were not alone. Dirk glanced up, and Gwen turned. The man came forward and bowed politely. Short and chubby and very blond—his hair looked almost white—he wore a brightly colored silkeen suit, all green and yellow, and a tiny black knit cap that stayed in place despite his bow.

“Arkin Ruark,” he said to Dirk.

“Dirk t’Larien.”

“Arkin is working with me on the project,” Gwen said.

“Project?”

She blinked. “Don’t you even know why I’m here?”

He didn’t. The whisperjewel had been sent from Worlorn, so he had known not much else than where to find her. “You’re an ecologist,” he said. “On Avalon . . .”

“Yes. At the Institute. A long time ago. I finished there, got my credentials, and I’ve been on High Kavalaan since. Until I was sent here.”

“Gwen is with the Ironjade Gathering,” Ruark said. He had a small, tight smile on his face. “Me, I’m representing Impril City Academy. Kimdiss. You know?”

Dirk nodded. Ruark was a Kimdissi then, an outworlder, from one of their universities.

“Impril and Ironjade, well, after the same thing, you know? Research on ecological interaction on Worlorn. Never really done properly during the Festival, the outworlds not being so strong on ecology, none of them. A science ai-forgotten, as the Emereli say. But that’s the project. Gwen and I knew each other from before, so we thought, well, here for the same reason, so it is good sense to work together and learn what we can learn.”

“I suppose,” Dirk said. He was not really overly interested in the project just then. He wanted to talk to Gwen. He looked at her. “You’ll have to tell me all about it later. When we talk. I imagine you want to talk.”

She gave him an odd look. “Yes, of course. We do have a lot to talk about.”

He picked up his bag. “Where to?” he asked. “I could probably do with a bath and some food.”

Gwen exchanged glances with Ruark. “Arkin and I were just talking about that. He can put you up. We’re in the same building. Only a few floors apart.”

Ruark nodded. “Gladly, gladly. Pleasure in doing for friends, and both of us are friend to Gwen, are we not?”

“Uh,” said Dirk. “I thought, somehow, that I would stay with you, Gwen.”

She could not look at him for a time. She looked at Ruark, at the ground, at the black night sky, before her eyes finally found his. “Perhaps,” she said, not smiling now, her voice careful. “But not right now. I don’t think it would be best, not immediately. But we’ll go home, of course. We have a car.”

“This way,” Ruark put in, before Dirk could frame his words. Something was very strange. He had played through the reunion scene a hundred times on board the Shuddering during the months of his voyage, and sometimes he had imagined it tender and loving, and sometimes it had been an angry confrontation, and often it had been tearful—but it had never been quite like this, awkward and at odd angles, with a stranger present throughout it all. He began to wonder exactly who Arkin Ruark was, and whether his relationship with Gwen was quite what they said it was. But then, they had hardly said anything. Without knowing what to say or to think, he shrugged and followed as they led him to their aircar.

The walk was quite short. The car, when they reached it, took Dirk aback. He had seen a lot of different types of aircars in his travels, but none quite like this one; huge and steel-gray, with curved and muscled triangular wings, it looked almost alive, like a great aerial manta ray fashioned in metal. A small cockpit with four seats was set between the wings, and beneath the wingtips he glimpsed ominous rods.

He looked at Gwen and pointed. “Are those lasers?”

She nodded, smiling just a little.

“What the hell are you flying?” Dirk asked. “It looks like a war machine. Are we going to be assaulted by Hrangans? I haven’t seen anything like that since we toured the Institute museums back on Avalon.”

Gwen laughed, took his bag from him, and tossed it into the back seat. “Get in,” she told him. “It is a perfectly fine aircar of High Kavalaan manufacture. They’ve only recently started turning out their own. It’s supposed to look like an animal, the black banshee. A flying predator, also the brother-beast of the Ironjade Gathering. Very big in their folklore, sort of a totem.”

She climbed in, behind the stick, and Ruark followed a bit awkwardly, vaulting over the armored wing into the back. Dirk did not move. “But it has lasers!” he insisted.

Gwen sighed. “They’re not charged, and never have been. Every car built on High Kavalaan has weapons of some sort. The culture demands it. And I don’t mean just Ironjade’s. Redsteel, Braith, and the Shanagate Holding are all the same.”

Dirk walked around the car and climbed in next to Gwen, but his face was blank. “What?”

“Those are the four Kavalar holdfast-coalitions,” she explained. “Think of them as small nations, or big families. They’re a little of both.”

“But why the lasers?”

“High Kavalaan is a violent planet,” Gwen replied.

Ruark gave a snort of laughter. “Ah, Gwen,” he said. “That is utter wrong, utter!”

“Wrong?” she snapped.

“Very,” Ruark said. “Yes, utter, because you are close to truth, half and not everything, worst lie of all.”

Dirk turned in his seat to look back at the chubby blond Kimdissi. “What?”

“High Kavalaan was a violent planet, truth. But now, truth is, the violence is the Kavalars. Hostile folk, each and every among them, xenophobes often, racists. Proud and jealous. With their highwars and their code duello, yes, and that is why Kavalar cars have guns. To fight with, in the air! I warn you, t’Larien—”

“Arkin!” Gwen said between her teeth, and Dirk started at the edged malice in her tone. She threw on the gravity grid suddenly, touched the stick, and the aircar wrenched forward and left the ground with a whine of protest, rising rapidly. The port below them was bright with light where the Shuddering of Forgotten Enemies stood among the lesser starships, shadowy everywhere else. Around it was darkness to the unseen horizon where black ground blended with blacker sky. Only a thin powder of stars lit the night above. This was the Fringe, with intergalactic space above and the dusky curtain of the Tempter’s Veil below, and the world seemed lonelier than Dirk had ever imagined.

Ruark had subsided, muttering, and a heavy silence lay over the car for a long moment.

“Arkin is from Kimdiss,” Gwen said finally, and she forced a chuckle. Dirk remembered her too well to be fooled, however; she was not one bit less tense than when she had snapped at Ruark a moment before.

“I don’t understand,” Dirk said, feeling quite stupid, since everyone seemed to think he should.

“You are no outworlder,” Ruark said. “Avalon, Baldur, whatever world, it doesn’t matter. Your people inside the Veil don’t know Kavalars.”

“Or Kimdissi,” Gwen said, a little more calmly.

Ruark grunted. “A sarcasm,” he told Dirk. “Kimdissi and Kavalars, well, we don’t get on, you know? So Gwen is telling you I’m all prejudiced and not to believe me.”

“Yes, Arkin,” she said. “Dirk, he doesn’t know High Kavalaan, doesn’t understand the culture or the people. Like all Kimdissi, he’ll tell you only the worst, but everything is more complex than he would credit. So remember that when this glib scoundrel starts working on you. It should be easy. In the old days, you were always telling me that every question has thirty sides.”

Dirk laughed. “Fair enough,” he said, “and true. Although these last few years I’ve begun to think that thirty is a bit low. I still don’t understand what this is all about, however. Take the car—does it come with your job? Or do you have to fly something like this just because you work for the Ironjade Gathering?”

“Ah,” Ruark said loudly. “You do not work for the Ironjade Gathering, Dirk. No, you are of them, you are not—two choices only. You are not of Ironjade, you do not work for Ironjade!”

“Yes,” said Gwen, the edge returning to her voice. “And I am of Ironjade. I wish you’d remember that, Arkin. Sometimes you begin to annoy me.”

“Gwen, Gwen,” Ruark said, sounding very flustered. “You are a friend, a soulmate, very. We have tussled great problems, us two. I would never offend, do not mean to. You are not a Kavalar though, never. For one, you are too much a woman, a true woman, not merely an eyn-kethi nor a betheyn.”

“No? I’m not? I wear the bond of jade-and-silver, though.” She glanced toward Dirk and lowered her voice. “For Jaan,” she said. “This is really his car, and that’s why I fly it, to answer your original question. For Jaan.”

Silence. The wind was the only noise, moving around them as they fell upward into blackness, tossing Gwen’s long straight hair and Dirk’s tangles. It knifed right through his thin Braqui clothing. He wondered briefly why the aircar had no bubble canopy, only a thin windscreen that was hardly any use at all. Then he folded his arms tight against his chest, and slid down into the seat. “Jaan?” he asked quietly. A question. The answer would come, he knew, and he dreaded it, just from the way that Gwen had spoken the name, with a sort of strange defiance.

“He doesn’t know,” Ruark said.

Gwen sighed, and Dirk could see her tense. “I’m sorry, Dirk. I thought you would know. It has been a long time. I thought, well, one of the people we both knew back on Avalon, one of them surely has told you.”

“I never see anyone anymore,” Dirk said carefully. “That we knew, together. You know. I travel a lot. Braque, Prometheus, Jamison’s World.” His voice rang hollow and inane in his ears. He paused and swallowed. “Who is Jaan?”

“Jaantony Riv Wolf high-Ironjade Vikary,” Ruark said.

“Jaan is my . . .” She hesitated. “It is not easy to explain. I am betheyn to Jaan, cro-betheyn to his teyn Garse.” She looked over, a brief glance away from the aircar instruments, then back again. There was no comprehension on Dirk’s face.

“Husband,” she said then, shrugging. “I’m sorry, Dirk. That’s not quite right, but it is the closest I can come in a single word. Jaan is my husband.”

Dirk, huddled low in his seat with his arms folded, said nothing. He was cold, and he hurt, and he wondered why he was there. He remembered the whisperjewel, and he still wondered. She had some reason for sending for him, surely, and in time she would tell him. And really, he could hardly have expected that she would be alone. At the port he had even thought, quite briefly, that perhaps Ruark . . . and that hadn’t bothered him.

When he had been silent for too long, Gwen looked over once again. “I’m sorry,” she repeated. “Dirk. Really. You should never have come.”

And he thought, She’s right.

The three of them flew on without speaking. Words had been said, and not the words that Dirk had wanted, but words that had changed nothing. He was here on Worlorn, and Gwen was still beside him, though suddenly a stranger. They were both strangers. He sat slumped in his seat, alone with his thoughts, while a cold wind stroked his face.

On Braque, somehow, he had thought that the whisperjewel meant she was calling him back, that she wanted him again. The only question that concerned him was whether he would go, whether he could return to her, whether Dirk t’Larien still could love and be loved. That had not been it at all, he knew now.

Send this memory, and I will come, and there will be no questions. That was the promise, the only promise. Nothing more.

He became angry. Why was she doing this to him? She had held the jewel and felt his feelings. She could have guessed. No need of hers could be worth the price of this remembering.

Then, finally, calm came back to Dirk t’Larien. With his eyes tight shut, he could see the canal on Braque again, and the lone black barge that had seemed so briefly important. And he remembered his resolve, to try again, to be as he had been, to come to her and give whatever he could give, whatever she might need—for himself, as well as for her.

He straightened with an effort, unfolded his arms, opened his eyes, and sat up into the biting wind. Then, deliberately, he looked at Gwen and smiled his old shy smile for her. “Ah, Jenny,” he said, “I’m sorry too. But it doesn’t matter. I didn’t know, but that doesn’t matter. I’m glad I came, and you should be glad too. Seven years is too long, right?”

She glanced at him, then back at her instruments, and licked her lips nervously. “Yes. Seven years is too long, Dirk.”

“Will I meet Jaan?”

She nodded. “And Garse too, his teyn.”

Below, somewhere, he heard water, a river lost in the darkness. It was gone quickly; they were moving quite fast. Dirk peered over the side of the aircar, down past the wings into the rushing black, then up. “You need more stars,” he said thoughtfully. “I feel as though I’m going blind.”

“I know what you mean,” Gwen said. She smiled, and quite suddenly Dirk felt better than he had for a long time.

“Remember the sky on Avalon?” he asked.

“Yes. Of course.”

“Lots of stars there. It was a beautiful world.”

“Worlorn has a beauty too,” she said. “How much do you know of it?”

“A little,” Dirk replied, still looking at her. “I know about the Festival, and that the planet is a rogue, and not much else. A woman on the ship told me that Tomo and Walberg discovered the place on their jaunt to the end of the galaxy.”

“Not quite,” said Gwen. “But the story has a certain charm to it. Anyway, everything you’ll see is part of the Festival. The whole planet is. All the worlds of the Fringe took part, and the culture of each is reflected here in one of the cities. There are fourteen cities, for the fourteen worlds of the Fringe. In between you’ve got the spacefield and the Common, which is sort of a park. We’re flying over it now. The Common is not very interesting, even by day. They had fairs and games there in the years of the Festival.”

“Where is your project?”

“The wilderness,” Ruark said. “Beyond the cities, beyond the mountainwall.”

Gwen said, “Look.”

Dirk looked. At the horizon he could vaguely make out a row of mountains, a jagged black barrier that climbed out of the Common to eclipse the lower stars. A spark of bloody light sat high upon one peak, and it grew as they drew near. Taller and higher it became, though not more brilliant; the color stayed a murky, threatening red that reminded Dirk somehow of the whisperjewel.

“Home,” Gwen announced as the light swelled. “The city Larteyn. Lar is Old Kavalar for sky. This is the city of High Kavalaan. Some people call it the Firefort.”

He could see why at a glance. Built into the shoulder of the mountain, rock beneath it and rock to its back, the Kavalar city was also a fortress—square and thick, massively walled, with narrow slit windows. Even the towers that rose behind the city walls were heavy and solid. And short; the Mountain loomed above them, its dark stone stained bloody by reflected light. But the lights of the city itself were not reflected; the walls and streets of Larteyn burned with a dull glowering fire of their own.

“Glowstone,” Gwen told him in answer to his unvoiced question. “It absorbs light during the day and gives it back at night. On High Kavalaan, it was used mostly for jewelry, but they quarried it by the ton and shipped it off to Worlorn for the Festival.”

“Baroque impressive,” Ruark said. “Kavalar impressive.” Dirk only nodded.

“You should have seen it in the old days,” Gwen said. “Larteyn drank from the seven suns by day and lit the range by night. Like a dagger of fire. The stones are fading now—the Wheel grows more distant every hour. In another decade the city will go dark as a burnt-out ember.”

“It doesn’t look very big,” Dirk said. “How many people did it hold?”

“A million, once. You’re just seeing the tip of the iceberg. The city is built into the mountain.”

“Very Kavalar,” Ruark said. “A deep holding, a fastness in stone. But empty now. Twenty people, last count, us including.”

The aircar passed over the outer wall, set flush to the cliff on the edge of the wide mountain ledge, to make one long straight drop past rock and glowstone. Below them Dirk saw wide walkways, and rows of slowly stirring pennants, and great carved gargoyles with burning glowstone eyes. The buildings were white stone and ebon wood, and on their flanks the rock fires were reflected in long red streaks, like open wounds on some hulking dark beast. They flew over towers and domes and streets, twisting alleys and wide boulevards, open courtyards and a huge many-tiered outdoor theater.

Empty, all empty. Not a figure moved in the red-drenched ways of Larteyn.

Gwen spiraled down to the roof of a square black tower. As she hovered and slowly faded the gravity grid to bring them in, Dirk noted two other cars in the airlot beneath them: a sleek yellow teardrop and a formidable old military flyer with the look of century-old war surplus. It was olive-green, square and sheathed in armor, with lasercannon on the forward hood and pulse-tubes on the rear.

She put their metal manta down between the two cars, and they vaulted out onto the roof. When they reached the bank of elevators, Gwen turned to face him, her face flushed and strange in the brooding reddish light. “It is late,” she said. “We had all better rest.”

Dirk did not question the dismissal. “Jaan?” he said.

“You’ll meet him tomorrow,” she replied. “I need a chance to talk to him first.”

“Why?” he asked, but Gwen had already turned and started toward the stairs. Then the tube arrived and Ruark put a hand on his shoulder and pulled him inside.

They rode downward, to sleep and to dreams.

![Once Upon A [Fallen] Time](https://i1.books-express.ro/bt/9781999264413/once-upon-a-fallen-time.jpg)