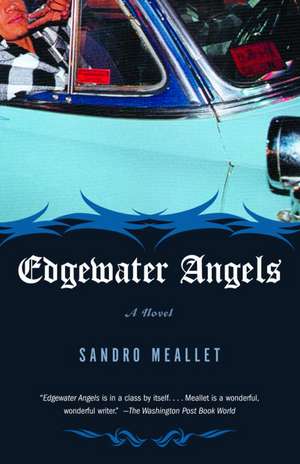

Edgewater Angels: Vintage Contemporaries

Autor Sandro Mealleten Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2002

Din seria Vintage Contemporaries

-

Preț: 109.95 lei

Preț: 109.95 lei -

Preț: 101.80 lei

Preț: 101.80 lei -

Preț: 96.52 lei

Preț: 96.52 lei -

Preț: 107.46 lei

Preț: 107.46 lei -

Preț: 91.77 lei

Preț: 91.77 lei -

Preț: 100.35 lei

Preț: 100.35 lei -

Preț: 111.51 lei

Preț: 111.51 lei -

Preț: 96.11 lei

Preț: 96.11 lei -

Preț: 96.93 lei

Preț: 96.93 lei -

Preț: 97.34 lei

Preț: 97.34 lei -

Preț: 111.92 lei

Preț: 111.92 lei -

Preț: 117.87 lei

Preț: 117.87 lei -

Preț: 95.92 lei

Preț: 95.92 lei -

Preț: 113.56 lei

Preț: 113.56 lei -

Preț: 101.88 lei

Preț: 101.88 lei -

Preț: 108.09 lei

Preț: 108.09 lei -

Preț: 115.42 lei

Preț: 115.42 lei -

Preț: 106.04 lei

Preț: 106.04 lei -

Preț: 119.87 lei

Preț: 119.87 lei -

Preț: 90.64 lei

Preț: 90.64 lei -

Preț: 87.84 lei

Preț: 87.84 lei -

Preț: 99.51 lei

Preț: 99.51 lei -

Preț: 105.41 lei

Preț: 105.41 lei -

Preț: 99.30 lei

Preț: 99.30 lei -

Preț: 120.26 lei

Preț: 120.26 lei -

Preț: 103.74 lei

Preț: 103.74 lei -

Preț: 100.98 lei

Preț: 100.98 lei -

Preț: 100.76 lei

Preț: 100.76 lei -

Preț: 89.19 lei

Preț: 89.19 lei -

Preț: 115.94 lei

Preț: 115.94 lei -

Preț: 101.24 lei

Preț: 101.24 lei -

Preț: 125.13 lei

Preț: 125.13 lei -

Preț: 89.50 lei

Preț: 89.50 lei -

Preț: 132.88 lei

Preț: 132.88 lei -

Preț: 139.63 lei

Preț: 139.63 lei -

Preț: 93.85 lei

Preț: 93.85 lei -

Preț: 106.45 lei

Preț: 106.45 lei -

Preț: 89.91 lei

Preț: 89.91 lei -

Preț: 107.92 lei

Preț: 107.92 lei -

Preț: 77.02 lei

Preț: 77.02 lei -

Preț: 125.21 lei

Preț: 125.21 lei -

Preț: 99.75 lei

Preț: 99.75 lei -

Preț: 112.11 lei

Preț: 112.11 lei -

Preț: 83.94 lei

Preț: 83.94 lei -

Preț: 97.15 lei

Preț: 97.15 lei -

Preț: 105.82 lei

Preț: 105.82 lei -

Preț: 87.13 lei

Preț: 87.13 lei -

Preț: 111.76 lei

Preț: 111.76 lei -

Preț: 129.78 lei

Preț: 129.78 lei -

Preț: 100.57 lei

Preț: 100.57 lei

Preț: 96.93 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 145

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.55€ • 19.29$ • 15.31£

18.55€ • 19.29$ • 15.31£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 22 martie-05 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375725616

ISBN-10: 037572561X

Pagini: 336

Dimensiuni: 130 x 207 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: Vintage Publishing

Seria Vintage Contemporaries

ISBN-10: 037572561X

Pagini: 336

Dimensiuni: 130 x 207 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: Vintage Publishing

Seria Vintage Contemporaries

Notă biografică

SANDRO MEALLET grew up in the projects of San Pedro, California, attended the University of California, Santa Cruz, on a basketball scholarship, and earned an MFA from The New School for Social Research and an MFA from Johns Hopkins University. He lives in California.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Sometimes we fished and crabbed behind the Maritime Museum or from the concrete pier next to the Catalina Terminal underneath the San Pedro side of the Vincent Thomas Bridge. Sometimes we silently borrowed a rowboat from the tugboat docks and paddled to Terminal Island across the harbor just in front of us and hid the rowboat under an unbusy wharf, then strolled over to Berth 300 with droplines, bait knives, and gotta-have donuts all in one to two buckets. Sometimes as an extra we got to watch the big gray pelicans just off the edge of Berth 300 headfirst themselves into the wavy seawater with the small trailer birds hot on their tails hoping to snatch and scoop away any overflow from the huge bills. And sometimes as we fished and watched the pelicans dive we tripped that Berth 300 was next to the federal penitentiary where rich businessmen spent their caught days. It was also where the gangster Al Capone from Chicago was prisoned many many years ago.

But mostly we headed to the Pink Building over by Deadman's Slip and back on the San Pedro side because the fish there bit hungry and came in spread-out schools. Often the fishschools jumped greedy from the water for the baited ends of our lowering droplines as if they couldn't wait for the frying pan. And always at each spot Tom-Su sat himself down alone with his dropline and stared into the water as he rocked back and forth.

Besides Tom-Su tagging along, the summer was a typical one for us. We fished and crabbed for most of each day and then headed to the San Pedro fishmarket. We sold our catch to locals before they got into the market—mostly Slavs and Italians who usually bought up everything—and split up the money between us. Whenever we couldn't sell the catch, it went to the one whose family needed it the most.

Tom-Su spoke very little English and understood even less. He was new from Korea and had a special way of treating caught fish that wiggled at the end of his dropline. We'd never seen anything like it.

"Tom-Su," one of us once said, "tell us the truth. Why do you bite the heads off of fish—while they're still alive!"

"Dead already." And that's all he said with a grin.

Tom-Su had bucked teeth and often drooled as if his mouth and jaw had been forever dentistnumbed. He always wore suspenders with his jeans, which were too high and tight around his waist. But we didn't know how to explain to him that it was goofy not only to have his pants flooding so hard, but to also be putting the visegrip on one's nuts. Me and the fellas wondered on and off just how we could make Tom-Su understand that down the line he wasn't gonna be a daddy, disrespecting his jewels the way he did. To top it off, Tom-Su sported a rope instead of a belt, definitely nailing down the supersorry look.

"Tom-Su," one of us once said, "pull your pants down a little so you don't hurt yourself!"

"You welcome." And that's all he said with a grin.

He was goofy in other ways, too. His baseball cap didn't fit his misshapen head; he moved as if he had rubber for bones; his skin was like a vanilla lampshade; and he would unexpectedly look at you with these cannibal-hungry eyes, complete with underbags and socketsinkage.

"Tom-Su," one of us once said to him, "what are you looking at?"

"That's good." And that's all he said with a grin.

The drool and cannibal eyes made some of us think of his food intake. And if Tom-Su was hungry we couldn't blame him. His diet was out there like Pluto. In his house once with his father not at home, we opened the fridge to see it packed wall-to-wall with seaweed. Green ocean plant in jars, in plastic bags, in boxes and open on the shelves, as if it were growing on vines. It gave the fridge a smell of musty freon. Hell, my teeth might've bucked on me too with nothing but seaweed for breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

"Tom-Su," one of us said to him in his kitchen, "is this all you eat?"

"Pretty good." And that's all he said with a grin as he opened up a cupboard to show us a year's supply of the stuff.

A seaweed breakfast? Know what I'm saying? Out there.

So when Tom-Su got around the live-and-kicking-for-life fish—and I mean meat and not some ocean plants—well, he got very involved with the catch the way none of us would, or could, or maybe even should. Early on, though, I guess we mainly thought his fish head biting a hobby within a hobby or maybe a creepy-gross natural ability—one you wouldn't want to be born with yourself.

But Tom-Su was cool with us because he carried our buckets wherever we headed along the waterfront and because he eventually depended on us—though none of us knew how much at the time. Wherever we went, he went, tagging along in his own speechless way, yessing his head, drifting off elsewhere, but always ready to bust out that buckedtooth grin.

In the beginning it had bugged us that Tom-Su went straight to his lonely area, sat down, and rocked rocked rocked. But eventually we got used to it or forgot about him altogether. After all, we had our fishing to do. Bait, for example, and not Tom-Su's state of mind, was something we had to give serious thinking to. If the fish weren't biting we had to get experimental on them. Sometimes we'd bring anchovies for bait. They were salty and tough and held fast to the hook. The fish loved to nibble then chomp at them. Sometimes, when we were interested in the bigger mackerel or bonita that brought us more than chumpchange at the fishmarket, we'd bring squid. Sometimes, when no other bait could be found, we'd bring lures and would be lucky to catch a couple of perch or buttermouth that were probably the dumbest and hungriest fish in the harbor. And sometimes we'd put small pear or apple wedges onto our hooks to catch some smelt and mackerel and even an occasional halibut. Bananas, grapes, peaches, plums, mangoes, oranges—none of them worked, though we'd once snagged a moray eel with a mediumsized strawberry and fought him for over an hour. After the moray snapped the dropline we talked about how good that strawberry must've tasted for him to want it so bad. A few times a tightlywadded piece of paper worked to catch a flounder; as did a button, a cube of stanky cheese, a corner of plywood, and an eyeball from a dead harbor cat to catch other things. The last several baits had been good only when the fishschools jumped like mad and our regular bait had run out and the buckets were near full. Oh, and once we accidentally caught a seagull using a chunk of plain bagel that the bird snatched right out of midair. We pulled the seagull in like a wild-and-desperate-winged kite and removing the hook from its beak dropped enough feathers for a wellstuffed baby's pillow.

One afternoon as we fought a recordsized bonita and yelled at each other to pull it up, Tom-Su sat to the side and didn't notice or care about the happenings at all; he didn't even budge—just stared straight down at the water. At the time we thought that he was maybe trying to spot the fish moving around beneath the surface or that maybe his brain shut down on him whenever he took his seat. But not until Tom-Su had fished with us for a good month did we realize that the rocking and numbheaded gaze were about something altogether different. Like that fish-head business. Only every so often, when he got a nibble, did Tom-Su come out of his trance, spring to his feet, and haul his dropline high over his head, fist by fist, until he yanked a fish from the water. Tom-Su then grabbed the fish from its jerking rise, brought it to his mouth in one fast motion, and clamped his teeth down right over the fish's head.

The previous May, Tom-Su and his mother had come to the Barton Hill Elementary principal's office. I'd been caught fighting Lowrider Louie again, this time because I'd looked at him a second too long, and was ordered to the office. Principal Dickerson sent Louie home on his reputation alone. Tom-Su sat in the chair next to me while his mother spoke to Dickerson at a nearby desk.

"He twelve year old," she said.

"Yes, I know, Mrs. Kim," said Dickerson. "He can't start here this summer or next fall. He's too old. Take him to the junior high—Dana Junior High, okay?"

"Tom-Su have small problem, Mr. Dick'son," she said and pointed to her temple. "No big problem; only small problem—very very small. And no speak English too good."

"Then take him to Harlem Shoemaker, Mrs. Kim," said Dickerson. Harlem Shoemaker was the school for retarded children. "I'm sure they'll have room for him there."

Tom-Su's mother gave a confused face as Dickerson wrote on a piece of paper. I looked at Tom-Su next to me. He had a little drool at the corner of his mouth and turned to me and buckedtooth-grinned from ear to ear. I smiled back. That was before he ever came fishing with us.

When he first moved in, we'd seen Tom-Su around the projects with his mother. They'd moved into the old Sanchez apartment. It was average and graycoated with rough grimy surfaces and grassyard enough for a one-yard run. There were hundreds of apartments just like it in the Rancho San Pedro housing projects. (The Sanchezes had moved back to Mexico because their youngest son, Julio, had been hit in the head by a stray bullet. It had traveled five or six blocks before finally getting to Julio.) Each time we'd seen Tom-Su he'd been stuck gluetight to his mother, moving beside her like some shrunken shadow of a person. It made him seem barely born or as if forever sunlightscared. Sometimes they'd even be seen holding hands, at which point we just knew something wasn't right with the guy. A mother and son holding hands? In our neighborhood it was unheard-of.

"—it's for special cases like Tom-Su," said Dickerson, handing her the note.

"No no," said his mother, "not right school. Please. Tom-Su father no like; he get so so mad."

"I'm sorry, Mrs. Kim," said Dickerson.

That night a terrible screaming argument that all of the Ranch could hear busted out in Tom-Su's apartment. The father mostly lost his lid and spit out one not-understandable sentence after another, sounding like some out-of-control Uzi. The only word we were hip to that came up again and again was "Tom-Su." The mother got in a few highpitched words of her own, but mostly seemed to take the bulletshot sentences left, right, left, right. Whenever she spoke we would hear a muffled wailing cry, too, that pricked every inch of our skin. The cries sounded like a person forced to watch the last of his blood dripdrop from his body. The cries came from Tom-Su. The father must really not've wanted his son at Harlem Shoemaker, we guessed, and must've taken the very suggestion as deeply personal, like it was a nasty negative on his name. Harlem Shoemaker, though, had a huge indoor swimming pool that we thought should've evened things up some. We didn't understand why Mr. Kim had to rip into his family the way he did. Or how his yelling could help any.

On our walk to the Pink Building the next morning we discovered a blankfaced Mrs. Kim and stonefaced Mr. Kim in the street in front of their apartment. Tom-Su stood by the door and watched them with this unshakable grin on his mug. Once, he'd looked our way as if casting a spell on us. Mrs. Kim had a suitcase by her side and a shoulder bag on her arm and spoke quietly to Mr. Kim, not really looking at him but up the empty street. Mr. Kim, though, glared hard at the side of her head, as if he'd wanted to bite her ear off. Then a taxi drove up, which had Mr. Kim grabbing onto his wife's arm and clipping some words hard into her ear as she struggled to free herself. They were quickly separated, though, by the taxi driver, who kept Mr. Kim from his wife as she scooted into the back of the taxi and locked her door. The Kims stared at each other through the window glass as the driver trunked the suitcase, stepped to his seat, and drove away. Mr. Kim watched the taxi head down the street and out of sight. When he walked back to his apartment he stopped at its door and stared his son in the eyes, who for some unknown reason maintained his grin. Together they looked nuttier than peanut butter. Mr. Kim glared at Tom-Su for what had to be a minute, then said one quick non-English brick of a word and smacked the boy on top of his head. Tom-Su bolted indoors. Abuse like that made us glad we didn't have any fathers in our homes. We continued on our walk to the Pink Building.

From the Hardcover edition.

But mostly we headed to the Pink Building over by Deadman's Slip and back on the San Pedro side because the fish there bit hungry and came in spread-out schools. Often the fishschools jumped greedy from the water for the baited ends of our lowering droplines as if they couldn't wait for the frying pan. And always at each spot Tom-Su sat himself down alone with his dropline and stared into the water as he rocked back and forth.

Besides Tom-Su tagging along, the summer was a typical one for us. We fished and crabbed for most of each day and then headed to the San Pedro fishmarket. We sold our catch to locals before they got into the market—mostly Slavs and Italians who usually bought up everything—and split up the money between us. Whenever we couldn't sell the catch, it went to the one whose family needed it the most.

Tom-Su spoke very little English and understood even less. He was new from Korea and had a special way of treating caught fish that wiggled at the end of his dropline. We'd never seen anything like it.

"Tom-Su," one of us once said, "tell us the truth. Why do you bite the heads off of fish—while they're still alive!"

"Dead already." And that's all he said with a grin.

Tom-Su had bucked teeth and often drooled as if his mouth and jaw had been forever dentistnumbed. He always wore suspenders with his jeans, which were too high and tight around his waist. But we didn't know how to explain to him that it was goofy not only to have his pants flooding so hard, but to also be putting the visegrip on one's nuts. Me and the fellas wondered on and off just how we could make Tom-Su understand that down the line he wasn't gonna be a daddy, disrespecting his jewels the way he did. To top it off, Tom-Su sported a rope instead of a belt, definitely nailing down the supersorry look.

"Tom-Su," one of us once said, "pull your pants down a little so you don't hurt yourself!"

"You welcome." And that's all he said with a grin.

He was goofy in other ways, too. His baseball cap didn't fit his misshapen head; he moved as if he had rubber for bones; his skin was like a vanilla lampshade; and he would unexpectedly look at you with these cannibal-hungry eyes, complete with underbags and socketsinkage.

"Tom-Su," one of us once said to him, "what are you looking at?"

"That's good." And that's all he said with a grin.

The drool and cannibal eyes made some of us think of his food intake. And if Tom-Su was hungry we couldn't blame him. His diet was out there like Pluto. In his house once with his father not at home, we opened the fridge to see it packed wall-to-wall with seaweed. Green ocean plant in jars, in plastic bags, in boxes and open on the shelves, as if it were growing on vines. It gave the fridge a smell of musty freon. Hell, my teeth might've bucked on me too with nothing but seaweed for breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

"Tom-Su," one of us said to him in his kitchen, "is this all you eat?"

"Pretty good." And that's all he said with a grin as he opened up a cupboard to show us a year's supply of the stuff.

A seaweed breakfast? Know what I'm saying? Out there.

So when Tom-Su got around the live-and-kicking-for-life fish—and I mean meat and not some ocean plants—well, he got very involved with the catch the way none of us would, or could, or maybe even should. Early on, though, I guess we mainly thought his fish head biting a hobby within a hobby or maybe a creepy-gross natural ability—one you wouldn't want to be born with yourself.

But Tom-Su was cool with us because he carried our buckets wherever we headed along the waterfront and because he eventually depended on us—though none of us knew how much at the time. Wherever we went, he went, tagging along in his own speechless way, yessing his head, drifting off elsewhere, but always ready to bust out that buckedtooth grin.

In the beginning it had bugged us that Tom-Su went straight to his lonely area, sat down, and rocked rocked rocked. But eventually we got used to it or forgot about him altogether. After all, we had our fishing to do. Bait, for example, and not Tom-Su's state of mind, was something we had to give serious thinking to. If the fish weren't biting we had to get experimental on them. Sometimes we'd bring anchovies for bait. They were salty and tough and held fast to the hook. The fish loved to nibble then chomp at them. Sometimes, when we were interested in the bigger mackerel or bonita that brought us more than chumpchange at the fishmarket, we'd bring squid. Sometimes, when no other bait could be found, we'd bring lures and would be lucky to catch a couple of perch or buttermouth that were probably the dumbest and hungriest fish in the harbor. And sometimes we'd put small pear or apple wedges onto our hooks to catch some smelt and mackerel and even an occasional halibut. Bananas, grapes, peaches, plums, mangoes, oranges—none of them worked, though we'd once snagged a moray eel with a mediumsized strawberry and fought him for over an hour. After the moray snapped the dropline we talked about how good that strawberry must've tasted for him to want it so bad. A few times a tightlywadded piece of paper worked to catch a flounder; as did a button, a cube of stanky cheese, a corner of plywood, and an eyeball from a dead harbor cat to catch other things. The last several baits had been good only when the fishschools jumped like mad and our regular bait had run out and the buckets were near full. Oh, and once we accidentally caught a seagull using a chunk of plain bagel that the bird snatched right out of midair. We pulled the seagull in like a wild-and-desperate-winged kite and removing the hook from its beak dropped enough feathers for a wellstuffed baby's pillow.

One afternoon as we fought a recordsized bonita and yelled at each other to pull it up, Tom-Su sat to the side and didn't notice or care about the happenings at all; he didn't even budge—just stared straight down at the water. At the time we thought that he was maybe trying to spot the fish moving around beneath the surface or that maybe his brain shut down on him whenever he took his seat. But not until Tom-Su had fished with us for a good month did we realize that the rocking and numbheaded gaze were about something altogether different. Like that fish-head business. Only every so often, when he got a nibble, did Tom-Su come out of his trance, spring to his feet, and haul his dropline high over his head, fist by fist, until he yanked a fish from the water. Tom-Su then grabbed the fish from its jerking rise, brought it to his mouth in one fast motion, and clamped his teeth down right over the fish's head.

The previous May, Tom-Su and his mother had come to the Barton Hill Elementary principal's office. I'd been caught fighting Lowrider Louie again, this time because I'd looked at him a second too long, and was ordered to the office. Principal Dickerson sent Louie home on his reputation alone. Tom-Su sat in the chair next to me while his mother spoke to Dickerson at a nearby desk.

"He twelve year old," she said.

"Yes, I know, Mrs. Kim," said Dickerson. "He can't start here this summer or next fall. He's too old. Take him to the junior high—Dana Junior High, okay?"

"Tom-Su have small problem, Mr. Dick'son," she said and pointed to her temple. "No big problem; only small problem—very very small. And no speak English too good."

"Then take him to Harlem Shoemaker, Mrs. Kim," said Dickerson. Harlem Shoemaker was the school for retarded children. "I'm sure they'll have room for him there."

Tom-Su's mother gave a confused face as Dickerson wrote on a piece of paper. I looked at Tom-Su next to me. He had a little drool at the corner of his mouth and turned to me and buckedtooth-grinned from ear to ear. I smiled back. That was before he ever came fishing with us.

When he first moved in, we'd seen Tom-Su around the projects with his mother. They'd moved into the old Sanchez apartment. It was average and graycoated with rough grimy surfaces and grassyard enough for a one-yard run. There were hundreds of apartments just like it in the Rancho San Pedro housing projects. (The Sanchezes had moved back to Mexico because their youngest son, Julio, had been hit in the head by a stray bullet. It had traveled five or six blocks before finally getting to Julio.) Each time we'd seen Tom-Su he'd been stuck gluetight to his mother, moving beside her like some shrunken shadow of a person. It made him seem barely born or as if forever sunlightscared. Sometimes they'd even be seen holding hands, at which point we just knew something wasn't right with the guy. A mother and son holding hands? In our neighborhood it was unheard-of.

"—it's for special cases like Tom-Su," said Dickerson, handing her the note.

"No no," said his mother, "not right school. Please. Tom-Su father no like; he get so so mad."

"I'm sorry, Mrs. Kim," said Dickerson.

That night a terrible screaming argument that all of the Ranch could hear busted out in Tom-Su's apartment. The father mostly lost his lid and spit out one not-understandable sentence after another, sounding like some out-of-control Uzi. The only word we were hip to that came up again and again was "Tom-Su." The mother got in a few highpitched words of her own, but mostly seemed to take the bulletshot sentences left, right, left, right. Whenever she spoke we would hear a muffled wailing cry, too, that pricked every inch of our skin. The cries sounded like a person forced to watch the last of his blood dripdrop from his body. The cries came from Tom-Su. The father must really not've wanted his son at Harlem Shoemaker, we guessed, and must've taken the very suggestion as deeply personal, like it was a nasty negative on his name. Harlem Shoemaker, though, had a huge indoor swimming pool that we thought should've evened things up some. We didn't understand why Mr. Kim had to rip into his family the way he did. Or how his yelling could help any.

On our walk to the Pink Building the next morning we discovered a blankfaced Mrs. Kim and stonefaced Mr. Kim in the street in front of their apartment. Tom-Su stood by the door and watched them with this unshakable grin on his mug. Once, he'd looked our way as if casting a spell on us. Mrs. Kim had a suitcase by her side and a shoulder bag on her arm and spoke quietly to Mr. Kim, not really looking at him but up the empty street. Mr. Kim, though, glared hard at the side of her head, as if he'd wanted to bite her ear off. Then a taxi drove up, which had Mr. Kim grabbing onto his wife's arm and clipping some words hard into her ear as she struggled to free herself. They were quickly separated, though, by the taxi driver, who kept Mr. Kim from his wife as she scooted into the back of the taxi and locked her door. The Kims stared at each other through the window glass as the driver trunked the suitcase, stepped to his seat, and drove away. Mr. Kim watched the taxi head down the street and out of sight. When he walked back to his apartment he stopped at its door and stared his son in the eyes, who for some unknown reason maintained his grin. Together they looked nuttier than peanut butter. Mr. Kim glared at Tom-Su for what had to be a minute, then said one quick non-English brick of a word and smacked the boy on top of his head. Tom-Su bolted indoors. Abuse like that made us glad we didn't have any fathers in our homes. We continued on our walk to the Pink Building.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Edgewater Angels is in a class by itself. . . . Meallet is a wonderful, wonderful writer.” –The Washington Post Book World

“Every now and then a good book comes from a place you might not expect. . . . This time that community is San Pedro, and the good book is Edgewater Angels.” —San Francisco Chronicle

“A beguiling coming of age story . . . [that] in its comic point of view, plot twists, and moral vision . . . reads like an unabashed descendant of Huck Finn with a bit of David Lynch’s passion . . . thrown in.” –The Village Voice

“An exuberantly absurdist look at growing up poor and shrouded by violence. . . . Meallet takes the most ominous event as an opportunity for black comedy, and finds true manhood in the least macho of behaviors.” –The New York Times Book Review

“Every now and then a good book comes from a place you might not expect. . . . This time that community is San Pedro, and the good book is Edgewater Angels.” —San Francisco Chronicle

“A beguiling coming of age story . . . [that] in its comic point of view, plot twists, and moral vision . . . reads like an unabashed descendant of Huck Finn with a bit of David Lynch’s passion . . . thrown in.” –The Village Voice

“An exuberantly absurdist look at growing up poor and shrouded by violence. . . . Meallet takes the most ominous event as an opportunity for black comedy, and finds true manhood in the least macho of behaviors.” –The New York Times Book Review

Descriere

With this astonishing debut, Meallet plunges into one of the country's harshest neighborhoods and emerges with a uniquely witty and wise urban coming-of-age novel as he chronicles the adolescence of Sunny Toomer, a streetwise urchin endlessly caught between right and wrong.