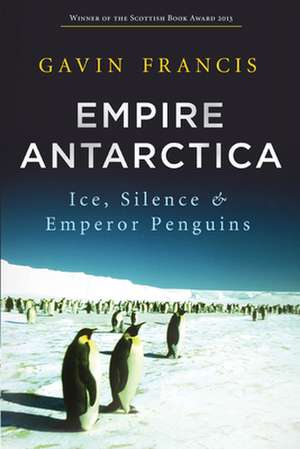

Empire Antarctica: Ice, Silence & Emperor Penguins

Autor Gavin Francisen Limba Engleză Paperback – 25 aug 2014

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Costa Book Awards (2013)

Gavin Francis fulfilled a lifetime's ambition when he spent fourteen months as the basecamp doctor at Halley, a profoundly isolated British research station on the Caird Coast of Antarctica. So remote, it is said to be easier to evacuate a casualty from the International Space Station than it is to bring someone out of Halley in winter.

Antarctica offered a year of unparalleled silence and solitude, with few distractions and very little human history, but also a rare opportunity. Throughout the year -- from a summer of perpetual sunshine to months of winter darkness -- Gavin Francis explores the world of great beauty conjured from the simplest of elements, the hardship of living at 50 c below zero and the unexpected comfort that this penguin community brings, for this is the story of one man and his fascination with the world's loneliest continent, as well as the emperor penguins who weather the winter with him. Combining an evocative narrative with a sublime sensitivity to the natural world, this is travel writing at its very best.

Antarctica offered a year of unparalleled silence and solitude, with few distractions and very little human history, but also a rare opportunity. Throughout the year -- from a summer of perpetual sunshine to months of winter darkness -- Gavin Francis explores the world of great beauty conjured from the simplest of elements, the hardship of living at 50 c below zero and the unexpected comfort that this penguin community brings, for this is the story of one man and his fascination with the world's loneliest continent, as well as the emperor penguins who weather the winter with him. Combining an evocative narrative with a sublime sensitivity to the natural world, this is travel writing at its very best.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 100.74 lei 3-5 săpt. | +11.24 lei 6-10 zile |

| Vintage Publishing – 6 noi 2013 | 100.74 lei 3-5 săpt. | +11.24 lei 6-10 zile |

| Counterpoint Press – 25 aug 2014 | 107.33 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 107.33 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 161

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.54€ • 21.19$ • 17.14£

20.54€ • 21.19$ • 17.14£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 05-19 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781619023406

ISBN-10: 1619023407

Pagini: 260

Dimensiuni: 142 x 221 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Editura: Counterpoint Press

ISBN-10: 1619023407

Pagini: 260

Dimensiuni: 142 x 221 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Editura: Counterpoint Press

Notă biografică

Gavin Francis was born in 1975 and brought up in Fife, Scotland. After qualifying from medical school in Edinburgh he spent ten years traveling, visiting all seven continents. He has worked in Africa and India, made several trips to the Artic, and crossed Eurasia and Australia by motorcycle. His first book, True North was published in 2008. He has lectured at the Scott Polar Research Institute in Cambridge and the Edinburgh Book Festival, and is a regular speaker at the Royal Scottish Geographical Society. He lives in Edinburgh.

Extras

It is said to be one of our oldest stories, embedded in humanity’s DNA, when a young man goes to a far-off land in search of a terrible or wondrous beast. The Epic of Gilgamesh, Jason and the Golden Fleece, Beowulf – they all fit the template. Bruce Chatwin added his Patagonian journey to the list. For years the idea of Antarctica had murmured in my ambition; a desire to go to the remotest land on our planet, to see one of the most wondrous beasts alive.

I wanted to live alongside emperor penguins in Antarctica. As a boy my most cared-for possession was a copy of Gerald Durrell’s The Amateur Naturalist. I was a diligent member of the Young Ornithologists Club and had memorised my Children’s Illustrated Book of Birds. When the thrill of local birdwatching waned I read about birds that never entered the seas or skies of Scotland. On a trip to Edinburgh Zoo I became fascinated by penguins’ waddling, boisterous gregariousness. There were glass cutaways in the penguins’ tank, it was possible to watch their underwater transformation from ungainly waddlers into lithe muscular hunters. They were so different from any kind of bird I knew that they captured my attention and my imagination.

Later I travelled in the High Arctic and loved the bright true purity I saw in the landscape there. But the Arctic is a ceaselessly roiling frozen ocean where birds and mammals shun mankind (or, in the case of polar bears, hunt them). I learned that penguins, on the other hand, showed no fear of human beings. I was enthralled by the idea of Antarctica, its solidity, silence, enormity, the mythical space it grew to occupy in my imagination, and wanted to meet for myself the birds that lived in it. I saw photographs of orni¬thologists sitting in rookeries surrounded by thousands of emperor penguins, relief on their faces, as if they felt accepted at last into avian society. I wondered if there at the end of the earth I might learn something from the emperors, of the purity of living in the physical senses, of a life without tangles of motives or the radio-chatter of the mind. They seemed to offer a welcome all too rare in the natural world, perhaps even a kind of forgiveness.

As I learned more about Antarctica I became captivated too by the stories of the early expeditions, particularly those of Scott, Shackleton, and the US Navy admiral, Richard Byrd. In the lush green afternoons of Scottish summers I read of Scott’s march to death on the Ross Ice Shelf, of Shackleton’s miraculous survival against all the odds, of Byrd’s winter alone, manning a meteoro¬logical station through months of polar darkness. Edward Wilson, Scott’s doctor and chief scientist, held a special fascination for me because of the stories of his tenacity, his kindness, but most of all his love of emperor penguins. I wanted to experience the Antarctic winter that these men had described so vividly, and see for myself that continent that for each had become an obsession.

There was another motive: the silence I imagined there in Antarctica drew me south. My life in Edinburgh often seemed frantic. There were always so many people to meet, things to learn, tasks to complete. At school, medical school and then in work, a succession of well-meaning teachers and mentors steered me towards a high-achieving career. But it felt wrong; I sensed that I needed to take a different path than that of the vertical career ladder and wondered if going to Antarctica might help me decide what to do next. When my life felt filled with obligations and responsibilities I found respite on long cycling and walking trips, periods under canvas or in trekkers’ huts where for days I would see no one and feel no need to speak. These trips always felt too short, and I wanted to throw myself into an extended stay some¬where remote, a place where for weeks and months I would have few responsibilities and unlimited mental space. Antarctica seemed like the only place that could also offer me that time, space and silence, while still ostensibly working as a doctor. I hoped that having so much time to think might make it clearer to me what path to take in my own future; whether to aim for a life of travel and expeditions, or commit to a profession and put down roots.

While still at medical school I learned that to ‘winter’ in the Antarctic – spend a full year there – I would have to land a job with the British Antarctic Survey, known as BAS. Of all the stations maintained by the British government only three have resident doctors, and of those three only two are part of continental Antarctica itself. Of those two, Rothera is based on an island off the Antarctic Peninsula, a glaciated serration of peaks that juts across the Antarctic Circle. The Peninsula is the continent’s extended finger, whetted by storms and testing the winds off Cape Horn. Only Halley is deep inside the Antarctic Circle, on an ice shelf calving from the body of the continent itself. And of all the BAS stations it is only at Halley that there is a breeding rookery of emperor penguins.

So there were three doctor jobs on offer when, as the leaves in Edinburgh coppered and fell, I took a train to Plymouth to be interviewed by the BAS Medical Unit.

I told them that I liked space and silence. I said I had hitched, hiked and camped alone all over the European Arctic. I said that I wanted to see for myself what it would be like to live through the polar night of an Antarctic winter. I had written to them for advice six years earlier, while still a medical student, and so they already knew that this was no sudden impulse, no escape from a failed love affair or a career’s dead end. They asked how I would cope with the claustrophobic pressure cooker of a tiny society where escape was impossible, and I told them that as long as I could safely take a walk outside I would be able to keep my peace. They told me that at Halley, once the ship had departed, there would be no way in and no way out for ten months. The only communication would be by dial-up satellite modem for text emails, and there would be no Internet access. I said that as long as I could take a trunk full of books I would be happy. They noticed that I liked to travel and asked how I would manage to spend a year in the same place, tied to a base that would be my only means of survival. I told them that maybe I had travelled enough and that it was time for me to stop for a while, gather my thoughts and experiences, and unravel them on the widest, blankest canvas on earth.

It was rumoured they only took you if you made it clear you would accept working on any base, as Antarctic logistics often forced a last-minute change of deployment. ‘Which would you prefer?’ they asked.

‘Halley would give me silence and space . . . and the emperor penguins,’ I told them, ‘but I also love mountains and the sea so I would be happy on South Georgia or Rothera. I would be happy to go wherever you wanted to send me.’

Later that evening my telephone rang. It was Iain Grant, the senior medical officer of the BAS Medical Unit. ‘How would you like to spend a winter at Halley?’ his voice said in my ear.

My hands shook so much that the telephone drummed against my ear. ‘I would be delighted,’ I said.

That night I didn’t sleep.

What was it, this continent to which I was headed? The Arctic has been written about and imagined for more than 2,000 years, but the imaginative tradition of Antarctica is still young and pliable; its very blankness lends it mutability and a sense of possibility. Antarctica has a younger cultural heritage than either railways or electric lights, both of which were invented long before anyone knew for sure there was a continent in the south at all. Its land¬scapes – in terms of geography and in terms of the mind – are still being worked out. When Antarctica was named it was just a blank on the map. Our ideas of it were forged only a century ago during what has been termed the Heroic Age of exploration, when creeping groups of humans, led by men like Robert Scott, Ernest Shackleton, Roald Amundsen and Douglas Mawson, arrived at its edges carrying flags, pemmican and reindeer-fur sleeping bags.

I wanted to live alongside emperor penguins in Antarctica. As a boy my most cared-for possession was a copy of Gerald Durrell’s The Amateur Naturalist. I was a diligent member of the Young Ornithologists Club and had memorised my Children’s Illustrated Book of Birds. When the thrill of local birdwatching waned I read about birds that never entered the seas or skies of Scotland. On a trip to Edinburgh Zoo I became fascinated by penguins’ waddling, boisterous gregariousness. There were glass cutaways in the penguins’ tank, it was possible to watch their underwater transformation from ungainly waddlers into lithe muscular hunters. They were so different from any kind of bird I knew that they captured my attention and my imagination.

Later I travelled in the High Arctic and loved the bright true purity I saw in the landscape there. But the Arctic is a ceaselessly roiling frozen ocean where birds and mammals shun mankind (or, in the case of polar bears, hunt them). I learned that penguins, on the other hand, showed no fear of human beings. I was enthralled by the idea of Antarctica, its solidity, silence, enormity, the mythical space it grew to occupy in my imagination, and wanted to meet for myself the birds that lived in it. I saw photographs of orni¬thologists sitting in rookeries surrounded by thousands of emperor penguins, relief on their faces, as if they felt accepted at last into avian society. I wondered if there at the end of the earth I might learn something from the emperors, of the purity of living in the physical senses, of a life without tangles of motives or the radio-chatter of the mind. They seemed to offer a welcome all too rare in the natural world, perhaps even a kind of forgiveness.

As I learned more about Antarctica I became captivated too by the stories of the early expeditions, particularly those of Scott, Shackleton, and the US Navy admiral, Richard Byrd. In the lush green afternoons of Scottish summers I read of Scott’s march to death on the Ross Ice Shelf, of Shackleton’s miraculous survival against all the odds, of Byrd’s winter alone, manning a meteoro¬logical station through months of polar darkness. Edward Wilson, Scott’s doctor and chief scientist, held a special fascination for me because of the stories of his tenacity, his kindness, but most of all his love of emperor penguins. I wanted to experience the Antarctic winter that these men had described so vividly, and see for myself that continent that for each had become an obsession.

There was another motive: the silence I imagined there in Antarctica drew me south. My life in Edinburgh often seemed frantic. There were always so many people to meet, things to learn, tasks to complete. At school, medical school and then in work, a succession of well-meaning teachers and mentors steered me towards a high-achieving career. But it felt wrong; I sensed that I needed to take a different path than that of the vertical career ladder and wondered if going to Antarctica might help me decide what to do next. When my life felt filled with obligations and responsibilities I found respite on long cycling and walking trips, periods under canvas or in trekkers’ huts where for days I would see no one and feel no need to speak. These trips always felt too short, and I wanted to throw myself into an extended stay some¬where remote, a place where for weeks and months I would have few responsibilities and unlimited mental space. Antarctica seemed like the only place that could also offer me that time, space and silence, while still ostensibly working as a doctor. I hoped that having so much time to think might make it clearer to me what path to take in my own future; whether to aim for a life of travel and expeditions, or commit to a profession and put down roots.

While still at medical school I learned that to ‘winter’ in the Antarctic – spend a full year there – I would have to land a job with the British Antarctic Survey, known as BAS. Of all the stations maintained by the British government only three have resident doctors, and of those three only two are part of continental Antarctica itself. Of those two, Rothera is based on an island off the Antarctic Peninsula, a glaciated serration of peaks that juts across the Antarctic Circle. The Peninsula is the continent’s extended finger, whetted by storms and testing the winds off Cape Horn. Only Halley is deep inside the Antarctic Circle, on an ice shelf calving from the body of the continent itself. And of all the BAS stations it is only at Halley that there is a breeding rookery of emperor penguins.

So there were three doctor jobs on offer when, as the leaves in Edinburgh coppered and fell, I took a train to Plymouth to be interviewed by the BAS Medical Unit.

I told them that I liked space and silence. I said I had hitched, hiked and camped alone all over the European Arctic. I said that I wanted to see for myself what it would be like to live through the polar night of an Antarctic winter. I had written to them for advice six years earlier, while still a medical student, and so they already knew that this was no sudden impulse, no escape from a failed love affair or a career’s dead end. They asked how I would cope with the claustrophobic pressure cooker of a tiny society where escape was impossible, and I told them that as long as I could safely take a walk outside I would be able to keep my peace. They told me that at Halley, once the ship had departed, there would be no way in and no way out for ten months. The only communication would be by dial-up satellite modem for text emails, and there would be no Internet access. I said that as long as I could take a trunk full of books I would be happy. They noticed that I liked to travel and asked how I would manage to spend a year in the same place, tied to a base that would be my only means of survival. I told them that maybe I had travelled enough and that it was time for me to stop for a while, gather my thoughts and experiences, and unravel them on the widest, blankest canvas on earth.

It was rumoured they only took you if you made it clear you would accept working on any base, as Antarctic logistics often forced a last-minute change of deployment. ‘Which would you prefer?’ they asked.

‘Halley would give me silence and space . . . and the emperor penguins,’ I told them, ‘but I also love mountains and the sea so I would be happy on South Georgia or Rothera. I would be happy to go wherever you wanted to send me.’

Later that evening my telephone rang. It was Iain Grant, the senior medical officer of the BAS Medical Unit. ‘How would you like to spend a winter at Halley?’ his voice said in my ear.

My hands shook so much that the telephone drummed against my ear. ‘I would be delighted,’ I said.

That night I didn’t sleep.

What was it, this continent to which I was headed? The Arctic has been written about and imagined for more than 2,000 years, but the imaginative tradition of Antarctica is still young and pliable; its very blankness lends it mutability and a sense of possibility. Antarctica has a younger cultural heritage than either railways or electric lights, both of which were invented long before anyone knew for sure there was a continent in the south at all. Its land¬scapes – in terms of geography and in terms of the mind – are still being worked out. When Antarctica was named it was just a blank on the map. Our ideas of it were forged only a century ago during what has been termed the Heroic Age of exploration, when creeping groups of humans, led by men like Robert Scott, Ernest Shackleton, Roald Amundsen and Douglas Mawson, arrived at its edges carrying flags, pemmican and reindeer-fur sleeping bags.

Descriere

Descriere de la o altă ediție sau format:

The author fulfilled a lifetime's ambition when he spent fourteen months as the base-camp doctor at Halley, an isolated British research station on the Caird Coast of Antarctica. Following the penguins throughout the year, the author talks about the hardship of living at 50 C below zero and the unexpected comfort that the penguin community bring.

The author fulfilled a lifetime's ambition when he spent fourteen months as the base-camp doctor at Halley, an isolated British research station on the Caird Coast of Antarctica. Following the penguins throughout the year, the author talks about the hardship of living at 50 C below zero and the unexpected comfort that the penguin community bring.

Premii

- Costa Book Awards Nominee, 2013