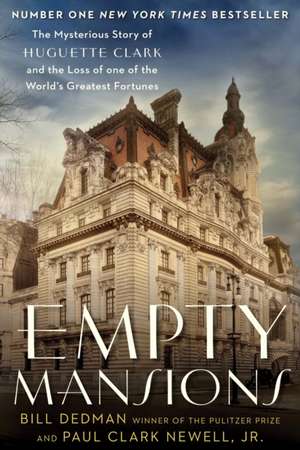

Empty Mansions

Autor Paul Clark Newell, Bill Dedmanen Limba Engleză Paperback – 3 iul 2014

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (1) | 114.36 lei 3-4 săpt. | +51.45 lei 4-10 zile |

| ATLANTIC BOOKS LTD – 3 iul 2014 | 114.36 lei 3-4 săpt. | +51.45 lei 4-10 zile |

| Hardback (1) | 232.52 lei 3-5 săpt. | +61.65 lei 4-10 zile |

| BALLANTINE BOOKS – 9 sep 2013 | 232.52 lei 3-5 săpt. | +61.65 lei 4-10 zile |

Preț: 114.36 lei

Preț vechi: 131.53 lei

-13% Nou

Puncte Express: 172

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.89€ • 22.76$ • 18.07£

21.89€ • 22.76$ • 18.07£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 24-31 martie

Livrare express 07-13 martie pentru 61.44 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781782394761

ISBN-10: 1782394761

Pagini: 496

Ilustrații: 73 b&w integrated and 3x8pp colour photographs

Dimensiuni: 157 x 232 x 38 mm

Greutate: 0.83 kg

Ediția:Main

Editura: ATLANTIC BOOKS LTD

ISBN-10: 1782394761

Pagini: 496

Ilustrații: 73 b&w integrated and 3x8pp colour photographs

Dimensiuni: 157 x 232 x 38 mm

Greutate: 0.83 kg

Ediția:Main

Editura: ATLANTIC BOOKS LTD

Recenzii

Advance praise for Empty Mansions

“Empty Mansions is a dazzlement and a wonder. Bill Dedman and Paul Newell unravel a great character, Huguette Clark, a shy soul akin to Boo Radley in To Kill a Mockingbird—if Boo’s father had been as rich as Rockefeller. This is an enchanting journey into the mysteries of the mind, a true-to-life exploration of strangeness and delight.”—Pat Conroy, author of The Death of Santini: The Story of a Father and His Son

“Empty Mansions is at once an engrossing portrait of a forgotten American heiress and a fascinating meditation on the crosswinds of extreme wealth. Hugely entertaining and well researched, Empty Mansions is a fabulous read.”—Amanda Foreman, author of A World on Fire

“In Empty Mansions, a unique American character emerges from the shadows. Through deep research and evocative writing, Bill Dedman and Paul Clark Newell, Jr., have expertly captured the arc of history covered by the remarkable Clark family, while solving a deeply personal mystery of wealth and eccentricity.”—Jon Meacham, author of Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power

“Who knew? Though virtually unknown today, W. A. Clark was one of the fifty richest Americans ever—copper baron, railroad builder, art collector, U.S. senator, and world-class scoundrel. Yet his daughter and heiress Huguette became a bizarre recluse. Empty Mansions reveals this mysterious family in sumptuous detail.”—John Berendt, author of Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil

“Empty Mansions is a mesmerizing tale that delivers all the ingredients of a top-notch mystery novel. But there is nothing fictional about this true, fully researched story of a fascinating and reclusive woman from an era of fabulous American wealth. Empty Mansions is a delicious read—once you start it, you will find it hard to put down.”—Kate Alcott, bestselling author of The Dressmaker

“More than a biography, more than a mystery, Empty Mansions is a real-life American Bleak House, an arresting tale about misplaced souls sketched on a canvas that stretches from coast to coast, from riotous mining camps to the gilded dwellings of the very, very rich.”—John A. Farrell, author of Clarence Darrow: Attorney for the Damned

“Empty Mansions is a dazzlement and a wonder. Bill Dedman and Paul Newell unravel a great character, Huguette Clark, a shy soul akin to Boo Radley in To Kill a Mockingbird—if Boo’s father had been as rich as Rockefeller. This is an enchanting journey into the mysteries of the mind, a true-to-life exploration of strangeness and delight.”—Pat Conroy, author of The Death of Santini: The Story of a Father and His Son

“Empty Mansions is at once an engrossing portrait of a forgotten American heiress and a fascinating meditation on the crosswinds of extreme wealth. Hugely entertaining and well researched, Empty Mansions is a fabulous read.”—Amanda Foreman, author of A World on Fire

“In Empty Mansions, a unique American character emerges from the shadows. Through deep research and evocative writing, Bill Dedman and Paul Clark Newell, Jr., have expertly captured the arc of history covered by the remarkable Clark family, while solving a deeply personal mystery of wealth and eccentricity.”—Jon Meacham, author of Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power

“Who knew? Though virtually unknown today, W. A. Clark was one of the fifty richest Americans ever—copper baron, railroad builder, art collector, U.S. senator, and world-class scoundrel. Yet his daughter and heiress Huguette became a bizarre recluse. Empty Mansions reveals this mysterious family in sumptuous detail.”—John Berendt, author of Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil

“Empty Mansions is a mesmerizing tale that delivers all the ingredients of a top-notch mystery novel. But there is nothing fictional about this true, fully researched story of a fascinating and reclusive woman from an era of fabulous American wealth. Empty Mansions is a delicious read—once you start it, you will find it hard to put down.”—Kate Alcott, bestselling author of The Dressmaker

“More than a biography, more than a mystery, Empty Mansions is a real-life American Bleak House, an arresting tale about misplaced souls sketched on a canvas that stretches from coast to coast, from riotous mining camps to the gilded dwellings of the very, very rich.”—John A. Farrell, author of Clarence Darrow: Attorney for the Damned

Notă biografică

Bill Dedman introduced the public to heiress Huguette Clark and her empty mansions through his compelling series of narratives for NBC, which became the most popular feature in the history of its news website, topping 110 million page views. He received the 1989 Pulitzer Prize in investigative reporting while writing for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution and has written for The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Boston Globe.

Paul Clark Newell, Jr., a cousin of Huguette Clark, has researched the Clark family history for twenty years, sharing many conversations with Huguette about her life and family. He received a rare private tour of Bellosguardo, her mysterious estate overlooking the Pacific Ocean in Santa Barbara.

Paul Clark Newell, Jr., a cousin of Huguette Clark, has researched the Clark family history for twenty years, sharing many conversations with Huguette about her life and family. He received a rare private tour of Bellosguardo, her mysterious estate overlooking the Pacific Ocean in Santa Barbara.

Extras

From day one at Doctors Hospital, Huguette had private nurses twenty-four hours a day. The nurse on the day shift, assigned randomly to Huguette in the spring of 1991, was Hadassah Peri. She would work for her “Madame” for twenty years, becoming, it seems probable, the wealthiest registered nurse in the world.

Doctors Hospital was not the place that a New Yorker with a lifethreatening illness normally would select. It was better known as a fashionable treatment center for the well-to-do, a society hospital, a great place for a face-lift or for drying out. Michael Jackson had been a patient, as had Marilyn Monroe, James Thurber, Clare Boothe Luce, and Eugene O’Neill. The fourteen-story brick structure on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, between Eighty-Seventh and Eighty-Eighth streets by a bend in the East River, gave the impression of being an apartment building or hotel, with a hair salon offering private appointments in patient rooms and a comfortable dining room where patients could order from the wine list if the doctor allowed. When it opened in 1929, it had no wards and no interns, allowed no charity care, and included hotel accommodations for family members of patients. In its early days, it was often used as a long-term residential hotel or spa, and finally in the 1970s it added modern coronary units and intensive care.

Huguette checked in to a room on the eleventh floor with a lovely view down to a city park and Gracie Mansion, the Federal-style home that is the official residence of the mayor of New York.

After living mostly alone at home for so many years, now Huguette was in a hospital with its constant noises and staff coming and going. At first she was a difficult patient, swathed in sheets and refusing to let anyone see her. A nurse wrote in the chart that she was “like a homeless person—no clothes, not in touch with the world, had not seen a doctor for 20 years, and threw everyone out of the room.”

A week into her stay, Huguette was evaluated by a social worker, who filled out the standard initial assessment. The patient, just short of age eighty-five, was scheduled for surgery to remove basal cell tumors and to reconstruct her lip, right cheek, and right eyelid. She had been “managing poorly at home—reclusive—not eating recently” and was dehydrated. Her only support system was her friend Suzanne Pierre, “helping with her affairs,” and a maid—no family. Her mental status was always awake and alert, but she was skittish: “Patient refused to speak with social worker. Patient has not been to doctor in many years—had refused medications in past. Patient anxious and uncooperative at times.”

Her plans after treatment? “Spoke with friend, Mrs. Pierre—feels patient will need convalescent care in facility but does not want to go to nursing home which she feels would be depressing. . . . Patient may need to go to a hotel with a nurse to recuperate.”

As for financial problems, “none noted.”

Huguette did not move on to a hotel. Within just over two months, she was an indefinite patient, a tenant, with Doctors Hospital charging her $829 a day. Eventually the rent rose to $1,200, or more than $400,000 a year.

Huguette had a series of surgeries in 1991 and 1992, with Dr. Jack Rudick removing malignant tumors and making initial repairs to her face. She was healthy, though she still needed a bit of plastic surgery, especially on her right eyelid. “It is not necessary,” she told her doctors. “I am not having any surgery. I don’t like needles.” She was not badly disfigured by the cancer. And there might have been another reason, Dr. Singman speculated. “This she has steadfastly put off,” he wrote in her chart in 1996, “I presume to avoid the final treatment and then possible discharge home.”

A board-certified specialist in internal medicine, cardiology, and geriatrics, Dr. Singman assured her that she could have round-the-clock nurses at home, and he would visit daily. “I had strongly urged that she go home,” he said. She was, however, “perfectly happy, content, to remain in the situation she was in.” When one of the first night nurses kept urging her to move back home, Huguette fired her. In the end, Dr. Singman accepted her decision, writing in her chart in 1996, “I fervently believe that this woman would not have survived if she had been discharged from the hospital.”

Dr. Singman’s backup, internist Dr. John Wolff, said he agreed. Huguette “was so content and so secure in the environment. There’s no question in my mind that’s really where she chose to be.” He brought her flowers on her birthday and liked to stop in. “She was a lovely woman, and we would talk. Her mind was clear. There was no confusion about her. Very warm, gracious, sweet, gentle, interested in other people, independent, guarded.”

Huguette was hardly ever sick. She refused to take a flu shot—she didn’t believe in medicine, she told her nurses, and felt that “nature should take its course.” Her only persistent medical issues were mild: osteopenia, a decrease of calcium in the bones not advanced enough to be called osteoporosis; a slightly elevated systolic blood pressure (150/80); and two nutrition issues, a mild electrolyte disorder and a mild salt depletion. Her illnesses passed quickly, usually with her refusing antibiotics. She had a bout of pneumonia, the seasonal flu, and a surgery to check out a suspicious lump that was benign.

In other words, from age eighty-five to well past one hundred, a stage when most people need elaborate pillboxes marked with the days of the week, Huguette was remarkably healthy, requiring no daily medications other than vitamins. Yet she was living in a hospital.

···

Dr. Singman said Huguette at first was “extremely frightened” of new people. She refused most medical treatments unless her day nurse, Hadassah, was there to hold her hand and talk calmingly. Hadassah and Huguette had a bond from the beginning, with Hadassah able to read Huguette’s feelings and help her overcome her distress. When they couldn’t reach Hadassah, the other nurses would sometimes pretend that they were talking with her on the phone, telling Huguette that Hadassah said that she had to eat now or she should allow them to check her blood pressure.

“You have to convince her,” explained Hadassah later. A small, compact woman with warm, dark eyes and black hair flecked with gray, Hadassah described patience as the key to her chemistry with Huguette. “You have to explain it to her, you have to educate her who is coming, what is that for—at times we have some difficulty.”

Hadassah Peri was born Gicela Tejada Oloroso in May 1950 to a politically prominent and eccentric family in the Philippine fishing town of Sapian. Gicela received a nursing degree before immigrating to the United States in 1972. She worked first at a hospital in Arkansas, then moved to New York in 1980. She passed her New York exams as a licensed practical nurse, then a registered nurse, and started working as a private-duty nurse. Born a Roman Catholic, she had married an Israeli immigrant and New York taxi driver, Daniel Peri, in 1982, converting to his Orthodox Judaism and using the name Hadassah Peri, although she didn’t change her name legally until 2011. Even today, she is a bit embarrassed about her English, though it’s quite good, despite some confusion over pronouns: “Madame love his favorite shoes.”

When she was assigned to Huguette, the Peris owned a small apartment in Brooklyn. They had three children born in the 1980s, two boys and a girl.

Private-duty nurses are temp workers, always hoping for a long-term assignment. Taking a day off means having a replacement nurse, one who might step into the regular role. So despite the Orthodox prohibition against working on Saturday, and despite having three school-age children, for many years Hadassah worked for Huguette from eight a.m. to eight p.m., twelve hours a day, seven days a week, fifty-two weeks a year. She was up and out of the house before her children left for school and home close to bedtime. It would be several years before she took a day off. Hadassah was paid $30 an hour, $2,520 a week, $131,040 a year, but she described her self-sacrifice for Huguette as extreme. “I give my life to Madame,” Hadassah said.

···

The private hospital room was perfectly ordinary, a small room for one patient with a hospital bed, recliner, chest of drawers, bedside table, small refrigerator, TV, radio, closet, small bathroom. “She like a simple room,” Hadassah said.

Once an outdoorsy youth, Huguette now didn’t want any daylight. The cancer had left her eyelid unable to close properly. She kept her shades drawn, though she often asked her nurses about the weather, and she did look out on the Fourth of July to watch the fireworks. The room wasn’t entirely dark, with an overhead light usually on, and Huguette had a reading lamp as well. Drawings by the nurses’ children and doctors’ grandchildren sometimes were hung on the walls. The door was closed, and Huguette would see only the visitors she knew. Dr. Singman called it a cocoon, a safe place, but not unpleasant.

The doctor said he asked Huguette once to see a psychiatrist, not because he thought she was mentally ill but because he thought talking with another doctor might help persuade her to return home. She declined to discuss it, and neither the doctor nor the hospital ever mentioned it again.

“The woman was an eccentric of the first order,” Dr. Singman said, but “she had perfect knowledge of her surroundings, she had excellent memory . . . a mind like a steel trap. . . . At that point she was perfectly happy, content, to remain in the situation she was in. . . . The hospital setting . . . was a form of security blanket for her. . . . I didn’t think there was going to be any great help from a psychiatrist to change her attitude about what she was doing. . . . The woman was perfectly conversant at all times, never demonstrated any . . . disturbances of her mind. . . . I didn’t think her behavior was that of one suffering from a psychiatric illness.” At most, said her doctor, she showed “eccentricity and neurotic behavior”—not exactly distinguishing characteristics in New York City.

Huguette dressed in hospital gowns, hardly ever wearing her clothes from home. When she was cold—and she was often cold—she would wear layered sweaters, always white button-front cashmere cardigans from Scotland, her only hint of luxury.

···

The daily routine began with Huguette drinking two cups of warm milk that the night nurse, Geraldine Lehane Coffey, had left for her. Hadassah would arrive with The New York Times. (Huguette always read the obituaries, as older people do, followed the progress of wars and weather emergencies, and delighted in finding stories about Japan and royalty.) Hadassah would greet Huguette and give her kisses. Huguette could walk to the bathroom by herself and give herself a sponge bath. Then Huguette would blow into the incentive spirometer, the little plastic tube where each deep breath makes the plastic ball rise, which helped ward off pneumonia. Huguette could make the ball go up five times, sometimes eight times. She would do coughing and deep-breathing exercises. Then it was time for breakfast: oatmeal and eggs, pureed, and her French coffee with hot milk, or café au lait.

Most of Huguette’s diet was liquid, taken through a straw because of the wound to her lip. Dinner was usually a soup that Hadassah had made at home, such as potato leek, made with eggs to provide protein. At night she would ask the nurse for a warm glass of milk before bed. Between meals, she drank Ensure nutritional drinks. For a special treat, Madame Pierre brought her steamed artichokes or asparagus with a rich hollandaise sauce, made in the classic French fashion with egg yolks and fresh butter, because Huguette said she couldn’t stand hospital food.

After breakfast, it was time for Huguette’s morning walk, three or four times around the room. She and Hadassah called this their “walk in Central Park.” Then it was personal time for Huguette. She made phone calls on her Princess telephone with the lighted dial, calling Madame Pierre sometimes three to five times a day. “Mrs. Clark liked to speak French with my grandmother,” said Suzanne’s granddaughter Kati Despretz Cruz, “because she didn’t want her nurses to understand what they were talking about.”

Huguette called her coordinator of art projects, Caterina Marsh, in California to make changes in a Japanese castle. She read The New York Times and followed the financial markets on CNN. “She would watch the stock,” said one of the night nurses, Primrose Mohiuddin, “and she would say to me, ‘Oh, NASDAQ has gone down. That’s terrible!’ ” She paid particular attention to news of presidents and royalty. “When President Clinton was in trouble,” her assistant Chris Sattler said, “she was asking Mrs. Pierre and me about the Monica Lewinsky thing. She didn’t get it, and she wanted us to explain it to her. And we sort of let it go, if you know what I mean.”

She kept a few personal items in shopping bags on the floor by the window. Her address book and recent correspondence. A deck of cards. Dr. Singman taught her solitaire and bought her a book of rules of card games, which she used to learn many variations.

Because Huguette kept information about herself tightly controlled, on a need-to-know basis, Dr. Singman knew little of her art projects and her correspondence with friends in France. To his view, solitaire was her main activity. “She was a wiz,” he said. “She could shuffle a deck like I haven’t seen anybody except in a gambling house.”

She no longer painted but would watch her videotapes of cartoons, studying the animation and enjoying the stories. She liked to make flip books of still images captured from videotapes, so she could see the animated stories in her hands. Her favorite cartoons were The Flintstones, The Jetsons, The Smurfs, and a Japanese series called Maya the Bee. These cartoons came in particularly handy when Huguette tired of a conversation with a doctor or hospital official. She’d start up The Smurfs as if to say, No, I’ve made up my mind.

And she would look at her photo albums, which contained snapshots from her early days with her father, mother, and sister. She’d show her nurses and doctors the photos: Andrée on a bicycle. Huguette on a horse at château de Petit-Bourg outside Paris. (She told them how the Germans had burned the house down.) The girls visiting their father’s copper mine in Butte. One of herself at her First Communion, and also surrounded by dolls on the porch of her father’s first mansion, in Butte, where she remembered the pansies on the stoop. Anna smiling as she sat on a park bench during a summer sojourn in Greenwich, Connecticut. Huguette’s Aunt Amelia, her mother’s sister, standing on the grand marble staircase at the old Clark mansion on Fifth Avenue. The rooms and gardens at Bellosguardo. Anna and W.A. on the beach at Trouville, laughing. Little Huguette in her Indian costume and headdress, hugging her father.

She would talk, Hadassah said, mostly about “her dear father, her dear mother, her dear sister, Aunt Amelia.” Huguette liked to tell the nurses about the summers at the beach in Trouville, how her father built the beautiful Columbia Gardens so the people of Butte could have something to enjoy, how Duke Kahanamoku carried her on his shoulders on a surfboard. And she would share somberly how her sister had died on the trip to Maine. “She talked dearly about that,” Hadassah said. “Talked all the time about her sister and parents. Yes, that affected her very much.”

Huguette’s eyesight had declined, but she was able to read with eyeglasses and then a magnifying glass until past age one hundred. Her hearing was poor in the right ear, but she could hear well out of her left if one talked right at it, and she refused a hearing aid. She didn’t deny that her hearing was poor, but she didn’t want anything put into her ears, nothing like her mother’s primitive squawk box. Hadassah bought a telephone with big numbers and adjustable volume, but Huguette refused to use it, saying she could hear fine with the regular phone.

Doctors and nurses described Huguette as a woman who knew her own mind. “She was remarkably clear,” said Karen Gottlieb, a floor nurse who brought her warm milk at bedtime. “Clear in her wants, and things she didn’t want. Yes meant yes, and no meant no.” Gottlieb said that she never saw any family try to visit, that Huguette’s real family seemed to be Hadassah.

The regular hospital staff rarely saw Huguette. One exception was in 2000, when Hadassah herself was in the hospital for back surgery. Huguette arranged for Hadassah to be in a room just down the hall, two or three doors away. Huguette then went to visit Hadassah, dressing up in street clothes and walking down the hall. She wore her favorite Daniel Green shoes.

“That’s one day everybody in the floor almost dropped dead,” Hadassah said. “They saw Madame coming out of the door with heel shoes.”

···

Hadassah described Huguette as “a beautiful lady. Very loving. Very respectful. Love people. Very refined lady. Very cultured. Good heart— good soul and good heart. Never hurt anybody. Very, very generous, Madame.”

Dr. Singman said he saw that Hadassah and Huguette were very close. “Hadassah was very good to her and was a good nurse for her and worked hard with her.”

Huguette’s first question in the morning would be “When is Hadassah coming?” She would call nearly every night to make sure Hadassah got home safely and to be reassured that Hadassah would be coming in the next day. Sometimes she’d call just as Hadassah got home, and the answering machine would pick up first. Here is a recording from about 2007, when Huguette was 101. We hear Huguette’s sweet, high-pitched French, and Hadassah’s Filipino accent, shouting to make sure she is heard.

Hadassah: Madame, I love you.

Huguette: I love you, too. Good night to you.

Hadassah: Have a good night.

Huguette: Have a good night.

Hadassah: Thank you, Madame.

Huguette: Will I see you tomorrow?

Hadassah: Yes, Madame.

Huguette: Thank you.

Hadassah: I love you.

Huguette: I love you, too.

Hadassah: Good night.

Huguette: Good night, Hadassah.

Doctors Hospital was not the place that a New Yorker with a lifethreatening illness normally would select. It was better known as a fashionable treatment center for the well-to-do, a society hospital, a great place for a face-lift or for drying out. Michael Jackson had been a patient, as had Marilyn Monroe, James Thurber, Clare Boothe Luce, and Eugene O’Neill. The fourteen-story brick structure on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, between Eighty-Seventh and Eighty-Eighth streets by a bend in the East River, gave the impression of being an apartment building or hotel, with a hair salon offering private appointments in patient rooms and a comfortable dining room where patients could order from the wine list if the doctor allowed. When it opened in 1929, it had no wards and no interns, allowed no charity care, and included hotel accommodations for family members of patients. In its early days, it was often used as a long-term residential hotel or spa, and finally in the 1970s it added modern coronary units and intensive care.

Huguette checked in to a room on the eleventh floor with a lovely view down to a city park and Gracie Mansion, the Federal-style home that is the official residence of the mayor of New York.

After living mostly alone at home for so many years, now Huguette was in a hospital with its constant noises and staff coming and going. At first she was a difficult patient, swathed in sheets and refusing to let anyone see her. A nurse wrote in the chart that she was “like a homeless person—no clothes, not in touch with the world, had not seen a doctor for 20 years, and threw everyone out of the room.”

A week into her stay, Huguette was evaluated by a social worker, who filled out the standard initial assessment. The patient, just short of age eighty-five, was scheduled for surgery to remove basal cell tumors and to reconstruct her lip, right cheek, and right eyelid. She had been “managing poorly at home—reclusive—not eating recently” and was dehydrated. Her only support system was her friend Suzanne Pierre, “helping with her affairs,” and a maid—no family. Her mental status was always awake and alert, but she was skittish: “Patient refused to speak with social worker. Patient has not been to doctor in many years—had refused medications in past. Patient anxious and uncooperative at times.”

Her plans after treatment? “Spoke with friend, Mrs. Pierre—feels patient will need convalescent care in facility but does not want to go to nursing home which she feels would be depressing. . . . Patient may need to go to a hotel with a nurse to recuperate.”

As for financial problems, “none noted.”

Huguette did not move on to a hotel. Within just over two months, she was an indefinite patient, a tenant, with Doctors Hospital charging her $829 a day. Eventually the rent rose to $1,200, or more than $400,000 a year.

Huguette had a series of surgeries in 1991 and 1992, with Dr. Jack Rudick removing malignant tumors and making initial repairs to her face. She was healthy, though she still needed a bit of plastic surgery, especially on her right eyelid. “It is not necessary,” she told her doctors. “I am not having any surgery. I don’t like needles.” She was not badly disfigured by the cancer. And there might have been another reason, Dr. Singman speculated. “This she has steadfastly put off,” he wrote in her chart in 1996, “I presume to avoid the final treatment and then possible discharge home.”

A board-certified specialist in internal medicine, cardiology, and geriatrics, Dr. Singman assured her that she could have round-the-clock nurses at home, and he would visit daily. “I had strongly urged that she go home,” he said. She was, however, “perfectly happy, content, to remain in the situation she was in.” When one of the first night nurses kept urging her to move back home, Huguette fired her. In the end, Dr. Singman accepted her decision, writing in her chart in 1996, “I fervently believe that this woman would not have survived if she had been discharged from the hospital.”

Dr. Singman’s backup, internist Dr. John Wolff, said he agreed. Huguette “was so content and so secure in the environment. There’s no question in my mind that’s really where she chose to be.” He brought her flowers on her birthday and liked to stop in. “She was a lovely woman, and we would talk. Her mind was clear. There was no confusion about her. Very warm, gracious, sweet, gentle, interested in other people, independent, guarded.”

Huguette was hardly ever sick. She refused to take a flu shot—she didn’t believe in medicine, she told her nurses, and felt that “nature should take its course.” Her only persistent medical issues were mild: osteopenia, a decrease of calcium in the bones not advanced enough to be called osteoporosis; a slightly elevated systolic blood pressure (150/80); and two nutrition issues, a mild electrolyte disorder and a mild salt depletion. Her illnesses passed quickly, usually with her refusing antibiotics. She had a bout of pneumonia, the seasonal flu, and a surgery to check out a suspicious lump that was benign.

In other words, from age eighty-five to well past one hundred, a stage when most people need elaborate pillboxes marked with the days of the week, Huguette was remarkably healthy, requiring no daily medications other than vitamins. Yet she was living in a hospital.

···

Dr. Singman said Huguette at first was “extremely frightened” of new people. She refused most medical treatments unless her day nurse, Hadassah, was there to hold her hand and talk calmingly. Hadassah and Huguette had a bond from the beginning, with Hadassah able to read Huguette’s feelings and help her overcome her distress. When they couldn’t reach Hadassah, the other nurses would sometimes pretend that they were talking with her on the phone, telling Huguette that Hadassah said that she had to eat now or she should allow them to check her blood pressure.

“You have to convince her,” explained Hadassah later. A small, compact woman with warm, dark eyes and black hair flecked with gray, Hadassah described patience as the key to her chemistry with Huguette. “You have to explain it to her, you have to educate her who is coming, what is that for—at times we have some difficulty.”

Hadassah Peri was born Gicela Tejada Oloroso in May 1950 to a politically prominent and eccentric family in the Philippine fishing town of Sapian. Gicela received a nursing degree before immigrating to the United States in 1972. She worked first at a hospital in Arkansas, then moved to New York in 1980. She passed her New York exams as a licensed practical nurse, then a registered nurse, and started working as a private-duty nurse. Born a Roman Catholic, she had married an Israeli immigrant and New York taxi driver, Daniel Peri, in 1982, converting to his Orthodox Judaism and using the name Hadassah Peri, although she didn’t change her name legally until 2011. Even today, she is a bit embarrassed about her English, though it’s quite good, despite some confusion over pronouns: “Madame love his favorite shoes.”

When she was assigned to Huguette, the Peris owned a small apartment in Brooklyn. They had three children born in the 1980s, two boys and a girl.

Private-duty nurses are temp workers, always hoping for a long-term assignment. Taking a day off means having a replacement nurse, one who might step into the regular role. So despite the Orthodox prohibition against working on Saturday, and despite having three school-age children, for many years Hadassah worked for Huguette from eight a.m. to eight p.m., twelve hours a day, seven days a week, fifty-two weeks a year. She was up and out of the house before her children left for school and home close to bedtime. It would be several years before she took a day off. Hadassah was paid $30 an hour, $2,520 a week, $131,040 a year, but she described her self-sacrifice for Huguette as extreme. “I give my life to Madame,” Hadassah said.

···

The private hospital room was perfectly ordinary, a small room for one patient with a hospital bed, recliner, chest of drawers, bedside table, small refrigerator, TV, radio, closet, small bathroom. “She like a simple room,” Hadassah said.

Once an outdoorsy youth, Huguette now didn’t want any daylight. The cancer had left her eyelid unable to close properly. She kept her shades drawn, though she often asked her nurses about the weather, and she did look out on the Fourth of July to watch the fireworks. The room wasn’t entirely dark, with an overhead light usually on, and Huguette had a reading lamp as well. Drawings by the nurses’ children and doctors’ grandchildren sometimes were hung on the walls. The door was closed, and Huguette would see only the visitors she knew. Dr. Singman called it a cocoon, a safe place, but not unpleasant.

The doctor said he asked Huguette once to see a psychiatrist, not because he thought she was mentally ill but because he thought talking with another doctor might help persuade her to return home. She declined to discuss it, and neither the doctor nor the hospital ever mentioned it again.

“The woman was an eccentric of the first order,” Dr. Singman said, but “she had perfect knowledge of her surroundings, she had excellent memory . . . a mind like a steel trap. . . . At that point she was perfectly happy, content, to remain in the situation she was in. . . . The hospital setting . . . was a form of security blanket for her. . . . I didn’t think there was going to be any great help from a psychiatrist to change her attitude about what she was doing. . . . The woman was perfectly conversant at all times, never demonstrated any . . . disturbances of her mind. . . . I didn’t think her behavior was that of one suffering from a psychiatric illness.” At most, said her doctor, she showed “eccentricity and neurotic behavior”—not exactly distinguishing characteristics in New York City.

Huguette dressed in hospital gowns, hardly ever wearing her clothes from home. When she was cold—and she was often cold—she would wear layered sweaters, always white button-front cashmere cardigans from Scotland, her only hint of luxury.

···

The daily routine began with Huguette drinking two cups of warm milk that the night nurse, Geraldine Lehane Coffey, had left for her. Hadassah would arrive with The New York Times. (Huguette always read the obituaries, as older people do, followed the progress of wars and weather emergencies, and delighted in finding stories about Japan and royalty.) Hadassah would greet Huguette and give her kisses. Huguette could walk to the bathroom by herself and give herself a sponge bath. Then Huguette would blow into the incentive spirometer, the little plastic tube where each deep breath makes the plastic ball rise, which helped ward off pneumonia. Huguette could make the ball go up five times, sometimes eight times. She would do coughing and deep-breathing exercises. Then it was time for breakfast: oatmeal and eggs, pureed, and her French coffee with hot milk, or café au lait.

Most of Huguette’s diet was liquid, taken through a straw because of the wound to her lip. Dinner was usually a soup that Hadassah had made at home, such as potato leek, made with eggs to provide protein. At night she would ask the nurse for a warm glass of milk before bed. Between meals, she drank Ensure nutritional drinks. For a special treat, Madame Pierre brought her steamed artichokes or asparagus with a rich hollandaise sauce, made in the classic French fashion with egg yolks and fresh butter, because Huguette said she couldn’t stand hospital food.

After breakfast, it was time for Huguette’s morning walk, three or four times around the room. She and Hadassah called this their “walk in Central Park.” Then it was personal time for Huguette. She made phone calls on her Princess telephone with the lighted dial, calling Madame Pierre sometimes three to five times a day. “Mrs. Clark liked to speak French with my grandmother,” said Suzanne’s granddaughter Kati Despretz Cruz, “because she didn’t want her nurses to understand what they were talking about.”

Huguette called her coordinator of art projects, Caterina Marsh, in California to make changes in a Japanese castle. She read The New York Times and followed the financial markets on CNN. “She would watch the stock,” said one of the night nurses, Primrose Mohiuddin, “and she would say to me, ‘Oh, NASDAQ has gone down. That’s terrible!’ ” She paid particular attention to news of presidents and royalty. “When President Clinton was in trouble,” her assistant Chris Sattler said, “she was asking Mrs. Pierre and me about the Monica Lewinsky thing. She didn’t get it, and she wanted us to explain it to her. And we sort of let it go, if you know what I mean.”

She kept a few personal items in shopping bags on the floor by the window. Her address book and recent correspondence. A deck of cards. Dr. Singman taught her solitaire and bought her a book of rules of card games, which she used to learn many variations.

Because Huguette kept information about herself tightly controlled, on a need-to-know basis, Dr. Singman knew little of her art projects and her correspondence with friends in France. To his view, solitaire was her main activity. “She was a wiz,” he said. “She could shuffle a deck like I haven’t seen anybody except in a gambling house.”

She no longer painted but would watch her videotapes of cartoons, studying the animation and enjoying the stories. She liked to make flip books of still images captured from videotapes, so she could see the animated stories in her hands. Her favorite cartoons were The Flintstones, The Jetsons, The Smurfs, and a Japanese series called Maya the Bee. These cartoons came in particularly handy when Huguette tired of a conversation with a doctor or hospital official. She’d start up The Smurfs as if to say, No, I’ve made up my mind.

And she would look at her photo albums, which contained snapshots from her early days with her father, mother, and sister. She’d show her nurses and doctors the photos: Andrée on a bicycle. Huguette on a horse at château de Petit-Bourg outside Paris. (She told them how the Germans had burned the house down.) The girls visiting their father’s copper mine in Butte. One of herself at her First Communion, and also surrounded by dolls on the porch of her father’s first mansion, in Butte, where she remembered the pansies on the stoop. Anna smiling as she sat on a park bench during a summer sojourn in Greenwich, Connecticut. Huguette’s Aunt Amelia, her mother’s sister, standing on the grand marble staircase at the old Clark mansion on Fifth Avenue. The rooms and gardens at Bellosguardo. Anna and W.A. on the beach at Trouville, laughing. Little Huguette in her Indian costume and headdress, hugging her father.

She would talk, Hadassah said, mostly about “her dear father, her dear mother, her dear sister, Aunt Amelia.” Huguette liked to tell the nurses about the summers at the beach in Trouville, how her father built the beautiful Columbia Gardens so the people of Butte could have something to enjoy, how Duke Kahanamoku carried her on his shoulders on a surfboard. And she would share somberly how her sister had died on the trip to Maine. “She talked dearly about that,” Hadassah said. “Talked all the time about her sister and parents. Yes, that affected her very much.”

Huguette’s eyesight had declined, but she was able to read with eyeglasses and then a magnifying glass until past age one hundred. Her hearing was poor in the right ear, but she could hear well out of her left if one talked right at it, and she refused a hearing aid. She didn’t deny that her hearing was poor, but she didn’t want anything put into her ears, nothing like her mother’s primitive squawk box. Hadassah bought a telephone with big numbers and adjustable volume, but Huguette refused to use it, saying she could hear fine with the regular phone.

Doctors and nurses described Huguette as a woman who knew her own mind. “She was remarkably clear,” said Karen Gottlieb, a floor nurse who brought her warm milk at bedtime. “Clear in her wants, and things she didn’t want. Yes meant yes, and no meant no.” Gottlieb said that she never saw any family try to visit, that Huguette’s real family seemed to be Hadassah.

The regular hospital staff rarely saw Huguette. One exception was in 2000, when Hadassah herself was in the hospital for back surgery. Huguette arranged for Hadassah to be in a room just down the hall, two or three doors away. Huguette then went to visit Hadassah, dressing up in street clothes and walking down the hall. She wore her favorite Daniel Green shoes.

“That’s one day everybody in the floor almost dropped dead,” Hadassah said. “They saw Madame coming out of the door with heel shoes.”

···

Hadassah described Huguette as “a beautiful lady. Very loving. Very respectful. Love people. Very refined lady. Very cultured. Good heart— good soul and good heart. Never hurt anybody. Very, very generous, Madame.”

Dr. Singman said he saw that Hadassah and Huguette were very close. “Hadassah was very good to her and was a good nurse for her and worked hard with her.”

Huguette’s first question in the morning would be “When is Hadassah coming?” She would call nearly every night to make sure Hadassah got home safely and to be reassured that Hadassah would be coming in the next day. Sometimes she’d call just as Hadassah got home, and the answering machine would pick up first. Here is a recording from about 2007, when Huguette was 101. We hear Huguette’s sweet, high-pitched French, and Hadassah’s Filipino accent, shouting to make sure she is heard.

Hadassah: Madame, I love you.

Huguette: I love you, too. Good night to you.

Hadassah: Have a good night.

Huguette: Have a good night.

Hadassah: Thank you, Madame.

Huguette: Will I see you tomorrow?

Hadassah: Yes, Madame.

Huguette: Thank you.

Hadassah: I love you.

Huguette: I love you, too.

Hadassah: Good night.

Huguette: Good night, Hadassah.