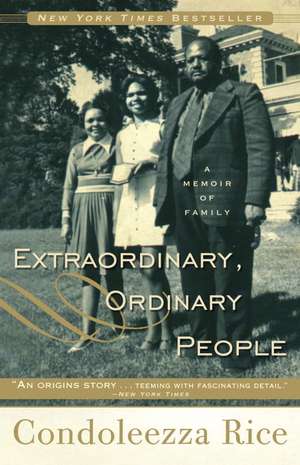

Extraordinary, Ordinary People: A Memoir of Family

Autor Condoleezza Riceen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 2011

But until she was 25 she never learned to swim.

Not because she wouldn't have loved to, but because when she was a little girl in Birmingham, Alabama, Commissioner of Public Safety Bull Connor decided he'd rather shut down the city's pools than give black citizens access.

Throughout the 1950's, Birmingham's black middle class largely succeeded in insulating their children from the most corrosive effects of racism, providing multiple support systems to ensure the next generation would live better than the last. But by 1963, when Rice was applying herself to her fourth grader's lessons, the situation had grown intolerable. Birmingham was an environment where blacks were expected to keep their head down and do what they were told -- or face violent consequences. That spring two bombs exploded in Rice’s neighborhood amid a series of chilling Klu Klux Klan attacks. Months later, four young girls lost their lives in a particularly vicious bombing.

So how was Rice able to achieve what she ultimately did?

Her father, John, a minister and educator, instilled a love of sports and politics. Her mother, a teacher, developed Condoleezza’s passion for piano and exposed her to the fine arts. From both, Rice learned the value of faith in the face of hardship and the importance of giving back to the community. Her parents’ fierce unwillingness to set limits propelled her to the venerable halls of Stanford University, where she quickly rose through the ranks to become the university’s second-in-command. An expert in Soviet and Eastern European Affairs, she played a leading role in U.S. policy as the Iron Curtain fell and the Soviet Union disintegrated. Less than a decade later, at the apex of the hotly contested 2000 presidential election, she received the exciting news – just shortly before her father’s death – that she would go on to the White House as the first female National Security Advisor.

As comfortable describing lighthearted family moments as she is recalling the poignancy of her mother’s cancer battle and the heady challenge of going toe-to-toe with Soviet leaders, Rice holds nothing back in this remarkably candid telling. This is the story of Condoleezza Rice that has never been told, not that of an ultra-accomplished world leader, but of a little girl – and a young woman -- trying to find her place in a sometimes hostile world and of two exceptional parents, and an extended family and community, that made all the difference.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 99.38 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 149

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.02€ • 19.86$ • 15.70£

19.02€ • 19.86$ • 15.70£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 26 martie-09 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307888471

ISBN-10: 0307888479

Pagini: 355

Ilustrații: 1 8-PAGE B&W INSERT 1 8-PAGE 4-C INSERT

Dimensiuni: 134 x 202 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.31 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

ISBN-10: 0307888479

Pagini: 355

Ilustrații: 1 8-PAGE B&W INSERT 1 8-PAGE 4-C INSERT

Dimensiuni: 134 x 202 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.31 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

Notă biografică

CONDOLEEZZA RICE was the 66th United States Secretary of State and the first black woman to ever hold that office. Prior to that, she was the first woman to serve as National Security Advisor. She currently teaches at Stanford University.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter One

Starting Early My parents were anxious to give me a head start in life—perhaps a little too anxious. My first memory of confronting them and in a way declaring my independence was a conversation concerning their ill-conceived attempt to send me to first grade at the ripe age of three. My mother was teaching at Fairfield Industrial High School in Alabama, and the idea was to enroll me in the elementary school located on the same campus. I don’t know how they talked the principal into going along, but sure enough, on the first day of school in September 1958, my mother took me by the hand and walked me into Mrs. Jones’ classroom.

I was terrified of the other children and of Mrs. Jones, and I refused to stay. Each day we would repeat the scene, and each day my father would have to pick me up and take me to my grandmother’s house, where I would stay until the school day ended. Finally I told my mother that I didn’t want to go back because the teacher wore the same skirt every morning. I am sure this was not literally true. Perhaps I somehow already understood that my mother believed in good grooming and appropriate attire. Anyway, the logic of my argument aside, Mother and Daddy got the point and abandoned their attempt at really early childhood education.

I now think back on that time and laugh. John and Angelena were prepared to try just about anything—or to let me try just about anything—that could be called an educational opportunity. They were convinced that education was a kind of armor shielding me against everything—even the deep racism in Birmingham and across America.

They were bred to those views. They were both born in the South at the height of segregation and racial prejudice—Mother just outside of Birmingham, Alabama, in 1924 and Daddy in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in 1923. They were teenagers during the Great Depression, old enough to remember but too young to adopt the overly cautious financial habits of their parents. They were of the first generation of middle-class blacks to attend historically black colleges—institutions that previously had been for the children of the black elite. And like so many of their peers, they rigorously controlled their environment to preserve their dignity and their pride.

Objectively, white people had all the power and blacks had none. “The White Man,” as my parents called “them,” controlled politics and the economy. This depersonalized collective noun spoke to the fact that my parents and their friends had few inter-actions with whites that were truly personal. In his wonderful book Colored People, Harvard professor Henry Louis “Skip” Gates Jr. recalled that his family and friends in West Virginia addressed white people by their professions—for example, “Mr. Policeman” or “Mr. Milkman.” Black folks in Birmingham didn’t even have that much contact. It was just “The White Man.”

Certainly, in any confrontation with a white person in Alabama you were bound to lose. But my parents believed that you could alter that equation through education, hard work, perfectly spoken English, and an appreciation for the “finer things” in “their” culture. If you were twice as good as they were, “they” might not like you but “they” had to respect you. One could find space for a fulfilling and productive life. There was nothing worse than being a helpless victim of your circumstances. My parents were determined to avoid that station in life. Needless to say, they were even more determined that I not end up that way.

My parents were not blue bloods. Yes, there were blue bloods who were black. These were the families that had emerged during Reconstruction, many of whose patriarchs had been freed well before slavery ended. Those families had bloodlines going back to black lawyers and doctors of the late nineteenth century; some of their ancestral lines even included political figures such as Hiram Rhodes Revels, the first black United States senator. There were pockets of these families in the Northeast and a large colony in Chicago. Some had attended Ivy League schools, but others, particularly those from the South, sent their children to such respected institutions as Meharry Medical College, Fisk, Morehouse, Spelman, and the Tuskegee Institute. In some cases these families had been college-educated for several generations.

My mother’s family was not from this caste, though it was more patrician than my father’s. Mattie Lula Parrom, my maternal grandmother, was the daughter of a high-ranking official, perhaps a bishop, in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Though details about her father, my great-grandfather, are sketchy, he was able to provide my grandmother with a first-rate education for a “colored” girl of that time. She was sent to a kind of finishing school called St. Mark’s Academy and was taught to play the piano by a European man who had come from -Vienna. Grandmother had rich brown skin and very high cheekbones, exposing American Indian blood that was obvious, if ill-defined. She was deeply religious, unfailingly trusting in God, and cultured.

My grandfather Albert Robinson Ray III was one of six siblings, extremely fair-skinned and possibly the product of a white father and black mother. His sister Nancy had light eyes and auburn hair. There was also apparently an Italian branch of the family on his mother’s side, memorialized in the names of successive generations. There are several Altos; my mother and her grandmother were named Angelena; my aunt was named Genoa (though, as southerners, we call her “Gen-OH-a”); my cousin is Lativia; and I am Condoleezza, all attesting to that part of our heritage.

Granddaddy Ray’s story is a bit difficult to tie down because he ran away from home when he was thirteen and did not reconnect with his family until he was an adult. According to family lore, Granddaddy used a tire iron to beat a white man who had assaulted his sister. Fearing for his life, he ran away and, later, found himself sitting in a train station with one token in his pocket in the wee hours of the morning. Many years later, Granddaddy would say that the sound of a train made him feel lonely. His last words before he died were to my mother. “Angelena,” he said, “we’re on this train alone.”

In any case, as Granddaddy sat alone in that station, a white man came over and asked what he was doing there at that hour of the night. For reasons that are not entirely clear, “Old Man Wheeler,” as he was known in our family, took my grandfather home and raised him with his sons. I remember very well going to my grandmother’s house in 1965 to tell her that Granddaddy had passed away at the hospital. She wailed and soon said, “Somebody call the Wheeler boys.” One came over to the house immediately. They were obviously just like family.

I’ve always been struck by this story because it speaks to the complicated history of blacks and whites in America. We came to this country as founding populations—Europeans and Africans. Our bloodlines have crossed and been intertwined by the ugly, sexual exploitation that was very much a part of slavery. Even in the depths of segregation, blacks and whites lived very close to one another. There are the familiar stories of black nannies who were “a part of the family,” raising the wealthy white children for whom they cared. But there are also inexplicable stories like that of my grandfather and the Wheelers.

We still have a lot of trouble with the truth of how tangled our family histories are. These legacies are painful and remind us of America’s birth defect: slavery. I remember all the fuss about Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings a few years back. Are we kidding? I thought. Of course Jefferson had black children. I can also remember being asked how I felt when I learned that I apparently had two white great-grandfathers, one on each side of the family. I just considered it a fact—no feelings were necessary. We all have white ancestors, and some whites have black ancestors. Once at a Stanford football game, my father and I sat in front of a white man who reached out his hand and said, “My name is Rice too. And I’m from the South.” The man blanched when my father suggested we might be related.

It is just easier not to talk about all of this or to obscure it with the term “African American,” which recalls the immigration narrative. There are groups such as Mexican Americans, Korean Americans, and German Americans who retain a direct link to their immigrant ancestors. But the fact is that only a portion of those with black skin are direct descendants of African immigrants as is President Obama, who was born of a white American mother and a Kenyan father. There is a second narrative, which involves immigrants from the West Indies such as Colin Powell’s parents. And what of the descendants of slaves in the old Confederacy? I prefer “black” and “white.” These terms are starker and remind us that the first Europeans and the first Africans came to this country together—the Africans in chains.

From the Hardcover edition.

Starting Early My parents were anxious to give me a head start in life—perhaps a little too anxious. My first memory of confronting them and in a way declaring my independence was a conversation concerning their ill-conceived attempt to send me to first grade at the ripe age of three. My mother was teaching at Fairfield Industrial High School in Alabama, and the idea was to enroll me in the elementary school located on the same campus. I don’t know how they talked the principal into going along, but sure enough, on the first day of school in September 1958, my mother took me by the hand and walked me into Mrs. Jones’ classroom.

I was terrified of the other children and of Mrs. Jones, and I refused to stay. Each day we would repeat the scene, and each day my father would have to pick me up and take me to my grandmother’s house, where I would stay until the school day ended. Finally I told my mother that I didn’t want to go back because the teacher wore the same skirt every morning. I am sure this was not literally true. Perhaps I somehow already understood that my mother believed in good grooming and appropriate attire. Anyway, the logic of my argument aside, Mother and Daddy got the point and abandoned their attempt at really early childhood education.

I now think back on that time and laugh. John and Angelena were prepared to try just about anything—or to let me try just about anything—that could be called an educational opportunity. They were convinced that education was a kind of armor shielding me against everything—even the deep racism in Birmingham and across America.

They were bred to those views. They were both born in the South at the height of segregation and racial prejudice—Mother just outside of Birmingham, Alabama, in 1924 and Daddy in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in 1923. They were teenagers during the Great Depression, old enough to remember but too young to adopt the overly cautious financial habits of their parents. They were of the first generation of middle-class blacks to attend historically black colleges—institutions that previously had been for the children of the black elite. And like so many of their peers, they rigorously controlled their environment to preserve their dignity and their pride.

Objectively, white people had all the power and blacks had none. “The White Man,” as my parents called “them,” controlled politics and the economy. This depersonalized collective noun spoke to the fact that my parents and their friends had few inter-actions with whites that were truly personal. In his wonderful book Colored People, Harvard professor Henry Louis “Skip” Gates Jr. recalled that his family and friends in West Virginia addressed white people by their professions—for example, “Mr. Policeman” or “Mr. Milkman.” Black folks in Birmingham didn’t even have that much contact. It was just “The White Man.”

Certainly, in any confrontation with a white person in Alabama you were bound to lose. But my parents believed that you could alter that equation through education, hard work, perfectly spoken English, and an appreciation for the “finer things” in “their” culture. If you were twice as good as they were, “they” might not like you but “they” had to respect you. One could find space for a fulfilling and productive life. There was nothing worse than being a helpless victim of your circumstances. My parents were determined to avoid that station in life. Needless to say, they were even more determined that I not end up that way.

My parents were not blue bloods. Yes, there were blue bloods who were black. These were the families that had emerged during Reconstruction, many of whose patriarchs had been freed well before slavery ended. Those families had bloodlines going back to black lawyers and doctors of the late nineteenth century; some of their ancestral lines even included political figures such as Hiram Rhodes Revels, the first black United States senator. There were pockets of these families in the Northeast and a large colony in Chicago. Some had attended Ivy League schools, but others, particularly those from the South, sent their children to such respected institutions as Meharry Medical College, Fisk, Morehouse, Spelman, and the Tuskegee Institute. In some cases these families had been college-educated for several generations.

My mother’s family was not from this caste, though it was more patrician than my father’s. Mattie Lula Parrom, my maternal grandmother, was the daughter of a high-ranking official, perhaps a bishop, in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Though details about her father, my great-grandfather, are sketchy, he was able to provide my grandmother with a first-rate education for a “colored” girl of that time. She was sent to a kind of finishing school called St. Mark’s Academy and was taught to play the piano by a European man who had come from -Vienna. Grandmother had rich brown skin and very high cheekbones, exposing American Indian blood that was obvious, if ill-defined. She was deeply religious, unfailingly trusting in God, and cultured.

My grandfather Albert Robinson Ray III was one of six siblings, extremely fair-skinned and possibly the product of a white father and black mother. His sister Nancy had light eyes and auburn hair. There was also apparently an Italian branch of the family on his mother’s side, memorialized in the names of successive generations. There are several Altos; my mother and her grandmother were named Angelena; my aunt was named Genoa (though, as southerners, we call her “Gen-OH-a”); my cousin is Lativia; and I am Condoleezza, all attesting to that part of our heritage.

Granddaddy Ray’s story is a bit difficult to tie down because he ran away from home when he was thirteen and did not reconnect with his family until he was an adult. According to family lore, Granddaddy used a tire iron to beat a white man who had assaulted his sister. Fearing for his life, he ran away and, later, found himself sitting in a train station with one token in his pocket in the wee hours of the morning. Many years later, Granddaddy would say that the sound of a train made him feel lonely. His last words before he died were to my mother. “Angelena,” he said, “we’re on this train alone.”

In any case, as Granddaddy sat alone in that station, a white man came over and asked what he was doing there at that hour of the night. For reasons that are not entirely clear, “Old Man Wheeler,” as he was known in our family, took my grandfather home and raised him with his sons. I remember very well going to my grandmother’s house in 1965 to tell her that Granddaddy had passed away at the hospital. She wailed and soon said, “Somebody call the Wheeler boys.” One came over to the house immediately. They were obviously just like family.

I’ve always been struck by this story because it speaks to the complicated history of blacks and whites in America. We came to this country as founding populations—Europeans and Africans. Our bloodlines have crossed and been intertwined by the ugly, sexual exploitation that was very much a part of slavery. Even in the depths of segregation, blacks and whites lived very close to one another. There are the familiar stories of black nannies who were “a part of the family,” raising the wealthy white children for whom they cared. But there are also inexplicable stories like that of my grandfather and the Wheelers.

We still have a lot of trouble with the truth of how tangled our family histories are. These legacies are painful and remind us of America’s birth defect: slavery. I remember all the fuss about Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings a few years back. Are we kidding? I thought. Of course Jefferson had black children. I can also remember being asked how I felt when I learned that I apparently had two white great-grandfathers, one on each side of the family. I just considered it a fact—no feelings were necessary. We all have white ancestors, and some whites have black ancestors. Once at a Stanford football game, my father and I sat in front of a white man who reached out his hand and said, “My name is Rice too. And I’m from the South.” The man blanched when my father suggested we might be related.

It is just easier not to talk about all of this or to obscure it with the term “African American,” which recalls the immigration narrative. There are groups such as Mexican Americans, Korean Americans, and German Americans who retain a direct link to their immigrant ancestors. But the fact is that only a portion of those with black skin are direct descendants of African immigrants as is President Obama, who was born of a white American mother and a Kenyan father. There is a second narrative, which involves immigrants from the West Indies such as Colin Powell’s parents. And what of the descendants of slaves in the old Confederacy? I prefer “black” and “white.” These terms are starker and remind us that the first Europeans and the first Africans came to this country together—the Africans in chains.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

"[Features] prose so spare it lays bare a child’s pain…full of raw vignettes, episodes that should jolt our post-racial sensibilities…[The book shows that] the key to Rice’s composure in office – which was a mix of womanly grace and analytical rigor – lies in the manner in which she was raised. In this, America owes a debt to John and Angelena Rice, parents extraordinarily pushy, parents extraordinarily brave."

—Wall Street Journal

“Surprisingly engrossing…One senses a romantic softness at the core of the steely woman Americans met during her years of public service. Rice’s reverence of her parents is touching, as is her abiding love for the Titusville of her youth.”

—Daily Beast

“Pays tribute to the people who truly shaped her [and] sets the record straight on aspects of her life that often flirt with myth.”

—USA Today

“An origins story…teeming with fascinating detail.”

—New York Times

“A thrilling, inspiring life of achievement.”

—Publishers Weekly

“A frank, poignant and loving portrait of a family that maintained its closeness through cancer, death, career ups and downs, and turbulent change in American society.”

—Booklist

“Vivid and heartfelt writing…Rice’s graceful memoir is a personal, multigenerational look into her own, and our country’s, past…Highly recommended.”

—Library Journal

"In this remarkably clear-eyed and candid autobiography, Rice focuses instead on her fascinating coming-of-age during the stormy civil rights years in Birmingham, Alabama."

—Bookpage

From the Hardcover edition.

—Wall Street Journal

“Surprisingly engrossing…One senses a romantic softness at the core of the steely woman Americans met during her years of public service. Rice’s reverence of her parents is touching, as is her abiding love for the Titusville of her youth.”

—Daily Beast

“Pays tribute to the people who truly shaped her [and] sets the record straight on aspects of her life that often flirt with myth.”

—USA Today

“An origins story…teeming with fascinating detail.”

—New York Times

“A thrilling, inspiring life of achievement.”

—Publishers Weekly

“A frank, poignant and loving portrait of a family that maintained its closeness through cancer, death, career ups and downs, and turbulent change in American society.”

—Booklist

“Vivid and heartfelt writing…Rice’s graceful memoir is a personal, multigenerational look into her own, and our country’s, past…Highly recommended.”

—Library Journal

"In this remarkably clear-eyed and candid autobiography, Rice focuses instead on her fascinating coming-of-age during the stormy civil rights years in Birmingham, Alabama."

—Bookpage

From the Hardcover edition.