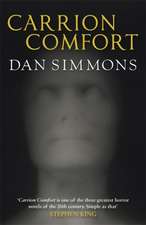

Fevre Dream

Autor George R. R. Martinen Limba Engleză Paperback – 10 noi 2011

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (3) | 53.90 lei 3-5 săpt. | +27.71 lei 10-14 zile |

| Orion Publishing Group – 10 noi 2011 | 53.90 lei 3-5 săpt. | +27.71 lei 10-14 zile |

| Bantam – 31 mar 2012 | 58.35 lei 3-5 săpt. | +19.29 lei 10-14 zile |

| Spectra Books – 31 aug 2004 | 107.22 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 53.90 lei

Preț vechi: 70.23 lei

-23% Nou

Puncte Express: 81

Preț estimativ în valută:

10.32€ • 10.73$ • 8.52£

10.32€ • 10.73$ • 8.52£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 22 martie-05 aprilie

Livrare express 11-15 martie pentru 37.70 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780575083042

ISBN-10: 0575083042

Pagini: 400

Dimensiuni: 200 x 135 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Editura: Orion Publishing Group

Locul publicării:London, United Kingdom

ISBN-10: 0575083042

Pagini: 400

Dimensiuni: 200 x 135 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Editura: Orion Publishing Group

Locul publicării:London, United Kingdom

Notă biografică

George R.R. Martin published his first story in 1971 and quickly rose to prominence, winning four Hugo andf two Nebula Awards in quick succession before he turned his attention to fantasy with the historical horror novel FEVRE DREAM, now a Fantasy Masterwork. Since then he has won every major award in the fields of fantasy, SF and horror. His magnificent epic saga A SONG OF ICE AND FIRE is redefining epic fantasy for a new generation. George R.R. Martin lives in New Mexico.

Extras

Chapter One

St. Louis, April 1857 Abner Marsh rapped the head of his hickory walking stick smartly on the hotel desk to get the clerk’s attention. “I’m here to see a man named York,” he said. “Josh York, I believe he calls hisself. You got such a man here?”

The clerk was an elderly man with spectacles. He jumped at the sound of the rap, then turned and spied Marsh and smiled. “Why, it’s Cap’n Marsh,” he said amiably. “Ain’t seen you for half a year, Cap’n. Heard about your misfortune, though. Terrible, just terrible. I been here since ’36 and I never seen no ice jam like that one.”

“Never you mind about that,” Abner Marsh said, annoyed. He had anticipated such comments. The Planters’ House was a popular hostelry among steamboatmen. Marsh himself had dined there regularly before that cruel winter. But since the ice jam he’d been staying away, and not only because of the prices. Much as he liked Planters’ House food, he was not eager for its brand of company: pilots and captains and mates, rivermen all, old friends and old rivals, and all of them knowing his misfortune. Abner Marsh wanted no man’s pity. “You just say where York’s room is,” he told the clerk peremptorily.

The clerk bobbed his head nervously. “Mister York won’t be in his room, Cap’n. You’ll find him in the dining room, taking his meal.”

“Now? At this hour?” Marsh glanced at the ornate hotel clock, then loosed the brass buttons of his coat and pulled out his own gold pocket watch. “Ten past midnight,” he said, incredulous. “You say he’s eatin’?”

“Yes sir, that he is. He chooses his own times, Mister York, and he’s not the sort you say no to, Cap’n.”

Abner Marsh made a rude noise deep in his throat, pocketed his watch, and turned away without a word, setting off across the richly appointed lobby with long, heavy strides. He was a big man, and not a patient one, and he was not accustomed to business meetings at midnight. He carried his walking stick with a flourish, as if he had never had a misfortune, and was still the man he had been.

The dining room was almost as grand and lavish as the main saloon on a big steamer, with cut-glass chandeliers and polished brass fixtures and tables covered with fine white linen and the best china and crystal. During normal hours, the tables would have been full of travelers and steamboatmen, but now the room was empty, most of the lights extinguished. Perhaps there was something to be said for midnight meetings after all, Marsh reflected; at least he would have to suffer no condolences. Near the kitchen door, two Negro waiters were talking softly. Marsh ignored them and walked to the far side of the room, where a well-dressed stranger was dining alone.

The man must have heard him approach, but he did not look up. He was busy spooning up mock turtle soup from a china bowl. The cut of his long black coat made it clear he was no riverman; an Easterner then, or maybe even a foreigner. He was big, Marsh saw, though not near so big as Marsh; seated, he gave the impression of height, but he had none of Marsh’s girth. At first Marsh thought him an old man, for his hair was white. Then, when he came closer, he saw that it was not white at all, but a very pale blond, and suddenly the stranger took on an almost boyish aspect. York was clean-shaven, not a mustache nor side whiskers on his long, cool face, and his skin was as fair as his hair. He had hands like a woman, Marsh thought as he stood over the table.

He tapped on the table with his stick. The cloth muffled the sound, made it a gentle summons. “You Josh York?” he said.

York looked up, and their eyes met.

Till the rest of his days were done, Abner Marsh remembered that moment, that first look into the eyes of Joshua York. Whatever thoughts he had had, whatever plans he had made, were sucked up in the maelstrom of York’s eyes. Boy and old man and dandy and foreigner, all those were gone in an instant, and there was only York, the man himself, the power of him, the dream, the intensity.

York’s eyes were gray, startlingly dark in such a pale face. His pupils were pinpoints, burning black, and they reached right into Marsh and weighed the soul inside him. The gray around them seemed alive, moving, like fog on the river on a dark night, when the banks vanish and the lights vanish and there is nothing in the world but your boat and the river and the fog. In those mists, Abner Marsh saw things; visions swift-glimpsed and then gone. There was a cool intelligence peering out of those mists. But there was a beast as well, dark and frightening, chained and angry, raging at the fog. Laughter and loneliness and cruel passion; York had all of that in his eyes.

But mostly there was force in those eyes, terrible force, a strength as relentless and merciless as the ice that had crushed Marsh’s dreams. Somewhere in that fog, Marsh could sense the ice moving, slow, so slow, and he could hear the awful splintering of his boats and all his hopes.

Abner Marsh had stared down many a man in his day, and he held his gaze for the longest time, his hand closed so hard around his stick that he feared he would snap it in two. But at last he looked away.

The man at the table pushed away his soup, gestured, and said, “Captain Marsh. I have been expecting you. Please join me.” His voice was mellow, educated, easy.

“Yes,” Marsh said, too softly. He pulled out the chair across from York and eased himself into it. Marsh was a massive man, six foot tall and three hundred pounds heavy. He had a red face and a full black beard that he wore to cover up a flat, pushed-in nose and a faceful of warts, but even the whiskers didn’t help much; they called him the ugliest man on the river, and he knew it. In his heavy blue captain’s coat with its double row of brass buttons, he was a fierce and imposing figure. But York’s eyes had drained him of his bluster. The man was a fanatic, Marsh decided. He had seen eyes like that before, in madmen and hell-raising preachers and once in the face of the man called John Brown, down in bleeding Kansas. Marsh wanted nothing to do with fanatics, with preachers, and abolitionists and temperance people.

But when York spoke, he did not sound like a fanatic. “My name is Joshua Anton York, Captain. J. A. York in business, Joshua to my friends. I hope that we shall be both business associates and friends, in time.” His tone was cordial and reasonable.

“We’ll see about that,” Marsh said, uncertain. The gray eyes across from him seemed aloof and vaguely amused now; whatever he had seen in them was gone. He felt confused.

“I trust you received my letter?”

“I got it right here,” Marsh said, pulling the folded envelope from the pocket of his coat. The offer had seemed an impossible stroke of fortune when it arrived, salvation for everything he feared lost. Now he was not so sure. “You want to go into the steamboat business, do you?” he said, leaning forward.

A waiter appeared. “Will you be dining with Mister York, Cap’n?”

“Please do,” York urged.

“I believe I will,” Marsh said. York might be able to outstare him, but there was no man on the river could outeat him. “I’ll have some of that soup, and a dozen oysters, and a couple of roast chickens with taters and stuff. Crisp ’em up good, mind you. And something to wash it all down with. What are you drinking, York?”

“Burgundy.”

“Fine, fetch me a bottle of the same.”

York looked amused. “You have a formidable appetite, Captain.”

“This is a for-mid-a-bul town,” Marsh said carefully, “and a formid-a-bul river, Mister York. Man’s got to keep his strength up. This ain’t New York, nor London neither.”

“I’m quite aware of that,” York said.

“Well, I hope so, if you’re going into steamboatin’. It’s the for-mid-a-bullest thing of all.”

“Shall we go directly to business, then? You own a packet line. I wish to buy a half-interest. Since you are here, I take it you are interested in my offer.”

“I’m considerable interested,” Marsh agreed, “and considerable puzzled, too. You look like a smart man. I reckon you checked me out before you wrote me this here letter.” He tapped it with his finger. “You ought to know that this last winter just about ruined me.

York said nothing, but something in his face bid Marsh continue.

“The Fevre River Packet Company, that’s me,” Marsh went on. “Called it that on account of where I was born, up on the Fevre near Galena, not ’cause I only worked that river, since I didn’t. I had six boats, working mostly the upper Mississippi trade, St. Louis to St. Paul, with some trips up the Fevre and the Illinois and the Missouri. I was doing just fine, adding a new boat or two most every year, thinking of moving into the Ohio trade, or maybe even New Orleans. But last July my Mary Clarke blew a boiler and burned, up near to Dubuque, burned right to the water line with a hundred dead. And this winter—this was a terrible winter. I had four of my boats wintering here at St. Louis. The Nicholas Perrot, the Dunleith, the Sweet Fevre, and my Elizabeth A., brand new, only four months in service and a sweet boat too, near 300 feet long with 12 big boilers, fast as any steamboat on the river. I was real proud of my lady Liz. She cost me $200,000, but she was worth every penny of it.” The soup arrived. Marsh tasted a spoonful and scowled. “Too hot,” he said. “Well, anyway, St. Louis is a good place to winter. Don’t freeze too bad down here, nor too long. This winter was different, though. Yes, sir. Ice jam. Damn river froze hard.” Marsh extended a huge red hand across the table, palm up, and slowly closed his fingers into a fist. “Put an egg in there and you get the idea, York. Ice can crush a steamboat easier than I can crush an egg. When it breaks up it’s even worse, big gorges sliding down the river, smashing up wharfs, levees, boats, most everything. Winter’s end, I’d lost my boats, all four of ’em. The ice took ’em away from me.”

“Insurance?” York asked.

Marsh set to his soup, sucking it up noisily. In between spoons, he shook his head. “I’m not a gambling man, Mister York. I never took no stock in insurance. It’s gambling, all it is, ’cept you’re bettin’ against yourself. What money I made, I put into my boats.”

York nodded. “I believe you still own one steamboat.”

“That I do,” Marsh said. He finished his soup and signaled for the next course. “The Eli Reynolds, a little 150-ton stern-wheeler. I been using her on the Illinois, ’cause she don’t draw much, and she wintered in Peoria, missed the worse of the ice. That’s my asset, sir, that’s what I got left. Trouble is, Mister York, the Eli Reynolds ain’t worth much. She only cost me $25,000 new, and that was back in ’50.”

“Seven years,” York said. “Not a very long time.”

Marsh shook his head. “Seven years is a powerful long time for a steamboat,” he said. “Most of ’em don’t last but four or five. River just eats ’em up. The Eli Reynolds was better built than most, but still, she ain’t got that long left.” Marsh started in on his oysters, scooping them up on the half shell and swallowing them whole, washing each one down with a healthy gulp of wine. “So I’m puzzled, Mister York,” he continued after a half-dozen oysters had disappeared. “You want to buy a half-share in my line, which ain’t got but one small, old boat. Your letter named a price. Too high a price. Maybe when I had six boats, then Fevre River Packets was worth that much. But not now.” He gulped down another oyster. “You won’t earn back your investment in ten years, not with the Reynolds. She can’t take enough freight, nor passengers neither.” Marsh wiped his lips on his napkin, and regarded the stranger across the table. The food had restored him, and now he felt like his own self again, in command of the situation. York’s eyes were intense, to be sure, but there was nothing there to fear.

“You need my money, Captain,” York said. “Why are you telling me this? Aren’t you afraid I will find another partner?”

“I don’t work that way,” Marsh said. “Been on the river thirty years, York. Rafted down to New Orleans when I was just a boy, and worked flatboats and keelboats both before steamers. I been a pilot and a mate and a striker, even a mud clerk. Been everything there is to be in this business, but one thing I never been, and that’s a sharper.”

“An honest man,” York said, with just enough of an edge in his voice so Marsh could not be sure if he was being mocked. “I am glad you saw fit to tell me the condition of your company, Captain. I knew it already, to be sure. My offer stands.”

“Why?” Marsh demanded gruffly. “Only a fool throws away money. You don’t look like no fool.”

The food arrived before York could answer. Marsh’s chickens were crisped up beautifully, just the way he liked them. He sawed off a leg and started in hungrily. York was served a thick cut of roasted beef, red and rare, swimming in blood and juice. Marsh watched him attack it, deftly, easily. His knife slid through the meat as if it were butter, never pausing to hack or saw, as Marsh so often did. He handled his fork like a gentleman, shifting hands when he set down his knife. Strength and grace; York had both in those long, pale hands of his, and Marsh admired that. He wondered that he had ever thought them a woman’s hands. They were white but strong, hard like the white of the keys of the grand piano in the main cabin of the Eclipse.

“Well?” Marsh prompted. “You ain’t answered my question.”

Joshua York paused for a moment. Finally he said, “You have been honest with me, Captain Marsh. I will not repay your honesty with lies, as I had intended. But I will not burden you with the truth, either. There are things I cannot tell you, things you would not care to know. Let me put my terms to you, under these conditions, and see if we can come to an agreement. If not, we shall part amiably.”

Marsh hacked the breast off his second chicken. “Go on,” he said. “I ain’t leaving.”

York put down his knife and fork and made a steeple of his fingers.

“For my own reasons, I want to be master of a steamboat. I want to travel the length of this great river, in comfort and privacy, not as passenger but as captain. I have a dream, a purpose. I seek friends and allies, and I have enemies, many enemies. The details are none of your concern. If you press me about them, I will tell you lies. Do not press me.” His eyes grew hard a moment, then softened as he smiled. “Your only interest need be my desire to own and command a steamboat, Captain. As you can tell, I am no riverman. I know nothing of steamboats, or the Mississippi, beyond what I have read in a few books and learned during the weeks I have spent in St. Louis. Obviously, I need an associate, someone who is familiar with the river and river people, someone who can manage the day-to-day operations of my boat, and leave me free to pursue my own purposes.

“This associate must have other qualities as well. He must be discreet, as I do not wish to have my behavior—which I admit to be sometimes peculiar—become the talk of the levee. He must be trustworthy, since I will give all management over into his hands. He must have courage. I do not want a weakling, or a superstitious man, or one who is overly religious. Are you a religious man, Captain?”

“No,” said Marsh. “Never cared for bible-thumpers, nor them for me.”

York smiled. “Pragmatic. I want a pragmatic man. I want a man who will concentrate on his own part of the business, and not ask too many questions of me. I value my privacy, and if sometimes my actions seem strange or arbitrary or capricious, I do not want them challenged. Do you understand my requirements?”

Marsh tugged thoughtfully on his beard. “And if I do?”

“We will become partners,” York said. “Let your lawyers and your clerks run your line. You will travel with me on the river. I will serve as captain. You can call yourself pilot, mate, co-captain, whatever you choose. The actual running of the boat I will leave to you. My orders will be infrequent, but when I do command, you will see to it that I am obeyed without question. I have friends who will travel with us, cabin passage, at no cost. I may see fit to give them positions on the boat, with such duties as I may deem fitting. You will not question these decisions. I may acquire other friends along the river, and bring them aboard as well. You will welcome them. If you can abide by such terms, Captain Marsh, we shall grow rich together and travel your river in ease and luxury.”

Abner Marsh laughed. “Well, maybe. But it ain’t my river, Mister York, and if you think we’re going to travel in luxury on the old Eli Reynolds, you’re going to be awful sore when you come on board. She’s a rackety old tub with some pretty poor accommodations, and most times she’s full of foreigners taking deck passage to one unlikely place or the other. I ain’t been on her in two years—old Cap’n Yoerger runs her for me now—but last time I rode her, she smelled pretty bad. You want luxury, you ought to see about buying into the Eclipse or the John Simonds.”

Joshua York sipped at his wine, and smiled. “I did not have the Eli Reynolds in mind, Captain Marsh.”

“She’s the only boat I got.”

York set down his wine. “Come,” he said, “let us settle up here. We can proceed up to my room, and discuss matters further.”

Marsh made a weak protest—the Planters’ House offered an excellent dessert menu, and he hated to pass it up. York insisted, however.

York’s room was a large, well-appointed suite, the best the hotel had to offer, and usually reserved for rich planters up from New Orleans. “Sit,” York said commandingly, gesturing Marsh to a large, comfortable chair in the sitting room. Marsh sat, while his host went into an inner chamber and returned a moment later, bearing a small iron-bound chest. He set it on a table and began to work the lock. “Come here,” he said, but Marsh had already risen to stand behind him. York threw back the lid.

“Gold,” Marsh said softly. He reached out and touched the coins, running them through his fingers, savoring the feel of the soft yellow metal, the gleam and the clatter of it. One coin he brought to his mouth and tasted. “Real enough,” he said, spitting. He chunked the coin back in the chest.

“Ten thousand dollars in twenty-dollar gold coins,” York said. “I have two other chests just like it, and letters of credit from banks in London, Philadelphia, and Rome for sums considerably larger. Accept my offer, Captain Marsh, and you shall have a second boat, one far grander than your Eli Reynolds. Or perhaps I should say that we shall have a second boat.” He smiled.

Abner Marsh had meant to turn down York’s offer. He needed the money bad enough, but he was a suspicious man with no use for mysteries, and York asked him to take too much on faith. The offer had sounded too good; Marsh was certain that danger lay hidden somewhere, and he would be the worse for it if he accepted. But now, staring at the color of York’s wealth, he felt his resolve weakening. “A new boat, you say?” he said weakly.

“Yes,” York replied, “and that is over and above the price I would pay you for a half-interest in your packet line.”

“How much . . .” Marsh began. His lips were dry. He licked them nervously. “How much are you willin’ to spend to build this new boat, Mister York?”

“How much is required?” York asked quietly.

Marsh took up a handful of gold coins, then let them rattle through his fingers back into the chest. The gleam of them, he thought, but all he said was, “You oughtn’t carry this much about with you, York. There’s scoundrels would kill you for one of them coins.”

“I can protect myself, Captain,” York said. Marsh saw the look in his eyes and felt cold. He pitied the robber who tried to take Joshua York’s gold.

“Will you take a walk with me? On the levee?”

“You haven’t given me my answer, Captain.”

“You’ll get your answer. Come first. Got something I want you to see.”

“Very well,” York said. He closed the lid of the chest, and the soft yellow gleam faded from the room, which suddenly seemed close and dim.

The night air was cool and moist. Their boots sent up echoes as they walked the dark, deserted streets, York with a limber grace and Marsh with heavy authority. York wore a loose pilot’s coat cut like a cape, and a tall old beaver hat that cast long shadows in the light of the half-moon. Marsh glared at the dark alleys between the bleak brick warehouses, and tried to present an aspect of solid, scowling strength sufficient to scare off ruffians.

The levee was crowded with steamboats, at least forty of them tied up to landing posts and wharfboats. Even at this hour all was not quiet. Huge stacks of freight threw black shadows in the moonlight, and they passed roustabouts lounging against crates and bales of hay, passing a bottle from hand to hand or smoking their cob pipes. Lights still burned in the cabin windows of a dozen or more boats. The Missouri packet Wyandotte was lit and building steam. They spied a man standing high up on the texas deck of one big side-wheel packet, looking down at them curiously. Abner Marsh led York past him, past the procession of darkened, silent steamers, their tall chimneys etched against the stars like a row of blackened trees with strange flowers on their tops.

Finally he stopped before a great ornate side-wheeler, freight piled high on her main deck, her stage raised against unwanted intruders as she nuzzled against her weathered old wharfboat. Even in the dimness of the half-moon the splendor of her was clear. No steamer on the levee was quite so big and proud.

“Yes?” Joshua York said quietly, respectfully. That might have decided it right there, Marsh thought later—the respect in his voice.

“That’s the Eclipse,” Marsh said. “See, her name is on the wheelhouse, there.” He jabbed with his stick. “Can you read it?”

“Quite well. I have excellent night vision. This is a special boat, then?”

“Hell yes, she’s special. She’s the Eclipse. Every goddamned man and boy on this river knows her. Old now—she was built back in ’52, five years ago. But she’s still grand. Cost $375,000, so they say, and worth all of it. There ain’t never been a bigger, fancier, more formid-a-bul boat than this one right here. I’ve studied her, taken passage on her. I know.” Marsh pointed. “She measures 365 feet by 40, and her grand saloon is 330 feet long, and you never seen nothin’ like it. Got a gold statue of Henry Clay at one end, and Andy Jackson at the other, the two of ’em glaring at each other the whole damn way. More crystal and silver and colored glass than the Planters’ House ever dreamed of, oil paintings, food like you ain’t never tasted, and mirrors—such mirrors. And all that’s nothin’ to her speed.

“Down below on the main deck she carries 15 boilers. Got an 11-foot stroke, I tell you, and there ain’t a boat on any river can run with her when Cap’n Sturgeon gets up her steam. She’s done eighteen miles an hour upstream, easy. Back in ’53, she set the record from New Orleans to Louisville. I know her time by heart. Four days, nine hours, thirty minutes, and she beat the goddamned A. L. Shotwell by fifty minutes, fast as the Shotwell is.” Marsh rounded to face York. “I hoped my Lady Liz would take the Eclipse some day, beat her time or race her head to head, but she never could of done it, I know that now. I was just foolin’ myself. I didn’t have the money it takes to build a boat that can take the Eclipse.

“You give me that money, Mister York, and you’ve got yourself a partner. There’s your answer, sir. You want half of Fevre River Packets, and a partner who runs things quiet and don’t ask you no questions ‘bout your business? Fine. Then you give me the money to build a steamboat like that.”

Joshua York stared at the big side-wheeler, serene and silent in the darkness, floating easily on the water, ready for all challengers. He turned to Abner Marsh with a smile on his lips and a dim flame in his dark eyes. “Done,” was all he said. And he extended his hand.

Marsh broke into a crooked, snaggle-toothed grin, wrapped York’s slim white hand within his own meaty paw, and squeezed. “Done, then,” he said loudly, and he brought all his massive strength to bear, squeezing and crushing, as he always did in business, to test the will and the courage of the men he dealt with. He squeezed until he saw the pain in their eyes.

But York’s eyes stayed clear, and his own hand clenched hard around Marsh’s with a strength that was surprising. Tighter and tighter it squeezed, and the muscles beneath that pale flesh coiled and corded like springs of iron, and Marsh swallowed hard and tried not to cry out.

York released his hand. “Come,” he said, clapping Marsh solidly across the shoulders and staggering him a bit. “We have plans to make.”

St. Louis, April 1857 Abner Marsh rapped the head of his hickory walking stick smartly on the hotel desk to get the clerk’s attention. “I’m here to see a man named York,” he said. “Josh York, I believe he calls hisself. You got such a man here?”

The clerk was an elderly man with spectacles. He jumped at the sound of the rap, then turned and spied Marsh and smiled. “Why, it’s Cap’n Marsh,” he said amiably. “Ain’t seen you for half a year, Cap’n. Heard about your misfortune, though. Terrible, just terrible. I been here since ’36 and I never seen no ice jam like that one.”

“Never you mind about that,” Abner Marsh said, annoyed. He had anticipated such comments. The Planters’ House was a popular hostelry among steamboatmen. Marsh himself had dined there regularly before that cruel winter. But since the ice jam he’d been staying away, and not only because of the prices. Much as he liked Planters’ House food, he was not eager for its brand of company: pilots and captains and mates, rivermen all, old friends and old rivals, and all of them knowing his misfortune. Abner Marsh wanted no man’s pity. “You just say where York’s room is,” he told the clerk peremptorily.

The clerk bobbed his head nervously. “Mister York won’t be in his room, Cap’n. You’ll find him in the dining room, taking his meal.”

“Now? At this hour?” Marsh glanced at the ornate hotel clock, then loosed the brass buttons of his coat and pulled out his own gold pocket watch. “Ten past midnight,” he said, incredulous. “You say he’s eatin’?”

“Yes sir, that he is. He chooses his own times, Mister York, and he’s not the sort you say no to, Cap’n.”

Abner Marsh made a rude noise deep in his throat, pocketed his watch, and turned away without a word, setting off across the richly appointed lobby with long, heavy strides. He was a big man, and not a patient one, and he was not accustomed to business meetings at midnight. He carried his walking stick with a flourish, as if he had never had a misfortune, and was still the man he had been.

The dining room was almost as grand and lavish as the main saloon on a big steamer, with cut-glass chandeliers and polished brass fixtures and tables covered with fine white linen and the best china and crystal. During normal hours, the tables would have been full of travelers and steamboatmen, but now the room was empty, most of the lights extinguished. Perhaps there was something to be said for midnight meetings after all, Marsh reflected; at least he would have to suffer no condolences. Near the kitchen door, two Negro waiters were talking softly. Marsh ignored them and walked to the far side of the room, where a well-dressed stranger was dining alone.

The man must have heard him approach, but he did not look up. He was busy spooning up mock turtle soup from a china bowl. The cut of his long black coat made it clear he was no riverman; an Easterner then, or maybe even a foreigner. He was big, Marsh saw, though not near so big as Marsh; seated, he gave the impression of height, but he had none of Marsh’s girth. At first Marsh thought him an old man, for his hair was white. Then, when he came closer, he saw that it was not white at all, but a very pale blond, and suddenly the stranger took on an almost boyish aspect. York was clean-shaven, not a mustache nor side whiskers on his long, cool face, and his skin was as fair as his hair. He had hands like a woman, Marsh thought as he stood over the table.

He tapped on the table with his stick. The cloth muffled the sound, made it a gentle summons. “You Josh York?” he said.

York looked up, and their eyes met.

Till the rest of his days were done, Abner Marsh remembered that moment, that first look into the eyes of Joshua York. Whatever thoughts he had had, whatever plans he had made, were sucked up in the maelstrom of York’s eyes. Boy and old man and dandy and foreigner, all those were gone in an instant, and there was only York, the man himself, the power of him, the dream, the intensity.

York’s eyes were gray, startlingly dark in such a pale face. His pupils were pinpoints, burning black, and they reached right into Marsh and weighed the soul inside him. The gray around them seemed alive, moving, like fog on the river on a dark night, when the banks vanish and the lights vanish and there is nothing in the world but your boat and the river and the fog. In those mists, Abner Marsh saw things; visions swift-glimpsed and then gone. There was a cool intelligence peering out of those mists. But there was a beast as well, dark and frightening, chained and angry, raging at the fog. Laughter and loneliness and cruel passion; York had all of that in his eyes.

But mostly there was force in those eyes, terrible force, a strength as relentless and merciless as the ice that had crushed Marsh’s dreams. Somewhere in that fog, Marsh could sense the ice moving, slow, so slow, and he could hear the awful splintering of his boats and all his hopes.

Abner Marsh had stared down many a man in his day, and he held his gaze for the longest time, his hand closed so hard around his stick that he feared he would snap it in two. But at last he looked away.

The man at the table pushed away his soup, gestured, and said, “Captain Marsh. I have been expecting you. Please join me.” His voice was mellow, educated, easy.

“Yes,” Marsh said, too softly. He pulled out the chair across from York and eased himself into it. Marsh was a massive man, six foot tall and three hundred pounds heavy. He had a red face and a full black beard that he wore to cover up a flat, pushed-in nose and a faceful of warts, but even the whiskers didn’t help much; they called him the ugliest man on the river, and he knew it. In his heavy blue captain’s coat with its double row of brass buttons, he was a fierce and imposing figure. But York’s eyes had drained him of his bluster. The man was a fanatic, Marsh decided. He had seen eyes like that before, in madmen and hell-raising preachers and once in the face of the man called John Brown, down in bleeding Kansas. Marsh wanted nothing to do with fanatics, with preachers, and abolitionists and temperance people.

But when York spoke, he did not sound like a fanatic. “My name is Joshua Anton York, Captain. J. A. York in business, Joshua to my friends. I hope that we shall be both business associates and friends, in time.” His tone was cordial and reasonable.

“We’ll see about that,” Marsh said, uncertain. The gray eyes across from him seemed aloof and vaguely amused now; whatever he had seen in them was gone. He felt confused.

“I trust you received my letter?”

“I got it right here,” Marsh said, pulling the folded envelope from the pocket of his coat. The offer had seemed an impossible stroke of fortune when it arrived, salvation for everything he feared lost. Now he was not so sure. “You want to go into the steamboat business, do you?” he said, leaning forward.

A waiter appeared. “Will you be dining with Mister York, Cap’n?”

“Please do,” York urged.

“I believe I will,” Marsh said. York might be able to outstare him, but there was no man on the river could outeat him. “I’ll have some of that soup, and a dozen oysters, and a couple of roast chickens with taters and stuff. Crisp ’em up good, mind you. And something to wash it all down with. What are you drinking, York?”

“Burgundy.”

“Fine, fetch me a bottle of the same.”

York looked amused. “You have a formidable appetite, Captain.”

“This is a for-mid-a-bul town,” Marsh said carefully, “and a formid-a-bul river, Mister York. Man’s got to keep his strength up. This ain’t New York, nor London neither.”

“I’m quite aware of that,” York said.

“Well, I hope so, if you’re going into steamboatin’. It’s the for-mid-a-bullest thing of all.”

“Shall we go directly to business, then? You own a packet line. I wish to buy a half-interest. Since you are here, I take it you are interested in my offer.”

“I’m considerable interested,” Marsh agreed, “and considerable puzzled, too. You look like a smart man. I reckon you checked me out before you wrote me this here letter.” He tapped it with his finger. “You ought to know that this last winter just about ruined me.

York said nothing, but something in his face bid Marsh continue.

“The Fevre River Packet Company, that’s me,” Marsh went on. “Called it that on account of where I was born, up on the Fevre near Galena, not ’cause I only worked that river, since I didn’t. I had six boats, working mostly the upper Mississippi trade, St. Louis to St. Paul, with some trips up the Fevre and the Illinois and the Missouri. I was doing just fine, adding a new boat or two most every year, thinking of moving into the Ohio trade, or maybe even New Orleans. But last July my Mary Clarke blew a boiler and burned, up near to Dubuque, burned right to the water line with a hundred dead. And this winter—this was a terrible winter. I had four of my boats wintering here at St. Louis. The Nicholas Perrot, the Dunleith, the Sweet Fevre, and my Elizabeth A., brand new, only four months in service and a sweet boat too, near 300 feet long with 12 big boilers, fast as any steamboat on the river. I was real proud of my lady Liz. She cost me $200,000, but she was worth every penny of it.” The soup arrived. Marsh tasted a spoonful and scowled. “Too hot,” he said. “Well, anyway, St. Louis is a good place to winter. Don’t freeze too bad down here, nor too long. This winter was different, though. Yes, sir. Ice jam. Damn river froze hard.” Marsh extended a huge red hand across the table, palm up, and slowly closed his fingers into a fist. “Put an egg in there and you get the idea, York. Ice can crush a steamboat easier than I can crush an egg. When it breaks up it’s even worse, big gorges sliding down the river, smashing up wharfs, levees, boats, most everything. Winter’s end, I’d lost my boats, all four of ’em. The ice took ’em away from me.”

“Insurance?” York asked.

Marsh set to his soup, sucking it up noisily. In between spoons, he shook his head. “I’m not a gambling man, Mister York. I never took no stock in insurance. It’s gambling, all it is, ’cept you’re bettin’ against yourself. What money I made, I put into my boats.”

York nodded. “I believe you still own one steamboat.”

“That I do,” Marsh said. He finished his soup and signaled for the next course. “The Eli Reynolds, a little 150-ton stern-wheeler. I been using her on the Illinois, ’cause she don’t draw much, and she wintered in Peoria, missed the worse of the ice. That’s my asset, sir, that’s what I got left. Trouble is, Mister York, the Eli Reynolds ain’t worth much. She only cost me $25,000 new, and that was back in ’50.”

“Seven years,” York said. “Not a very long time.”

Marsh shook his head. “Seven years is a powerful long time for a steamboat,” he said. “Most of ’em don’t last but four or five. River just eats ’em up. The Eli Reynolds was better built than most, but still, she ain’t got that long left.” Marsh started in on his oysters, scooping them up on the half shell and swallowing them whole, washing each one down with a healthy gulp of wine. “So I’m puzzled, Mister York,” he continued after a half-dozen oysters had disappeared. “You want to buy a half-share in my line, which ain’t got but one small, old boat. Your letter named a price. Too high a price. Maybe when I had six boats, then Fevre River Packets was worth that much. But not now.” He gulped down another oyster. “You won’t earn back your investment in ten years, not with the Reynolds. She can’t take enough freight, nor passengers neither.” Marsh wiped his lips on his napkin, and regarded the stranger across the table. The food had restored him, and now he felt like his own self again, in command of the situation. York’s eyes were intense, to be sure, but there was nothing there to fear.

“You need my money, Captain,” York said. “Why are you telling me this? Aren’t you afraid I will find another partner?”

“I don’t work that way,” Marsh said. “Been on the river thirty years, York. Rafted down to New Orleans when I was just a boy, and worked flatboats and keelboats both before steamers. I been a pilot and a mate and a striker, even a mud clerk. Been everything there is to be in this business, but one thing I never been, and that’s a sharper.”

“An honest man,” York said, with just enough of an edge in his voice so Marsh could not be sure if he was being mocked. “I am glad you saw fit to tell me the condition of your company, Captain. I knew it already, to be sure. My offer stands.”

“Why?” Marsh demanded gruffly. “Only a fool throws away money. You don’t look like no fool.”

The food arrived before York could answer. Marsh’s chickens were crisped up beautifully, just the way he liked them. He sawed off a leg and started in hungrily. York was served a thick cut of roasted beef, red and rare, swimming in blood and juice. Marsh watched him attack it, deftly, easily. His knife slid through the meat as if it were butter, never pausing to hack or saw, as Marsh so often did. He handled his fork like a gentleman, shifting hands when he set down his knife. Strength and grace; York had both in those long, pale hands of his, and Marsh admired that. He wondered that he had ever thought them a woman’s hands. They were white but strong, hard like the white of the keys of the grand piano in the main cabin of the Eclipse.

“Well?” Marsh prompted. “You ain’t answered my question.”

Joshua York paused for a moment. Finally he said, “You have been honest with me, Captain Marsh. I will not repay your honesty with lies, as I had intended. But I will not burden you with the truth, either. There are things I cannot tell you, things you would not care to know. Let me put my terms to you, under these conditions, and see if we can come to an agreement. If not, we shall part amiably.”

Marsh hacked the breast off his second chicken. “Go on,” he said. “I ain’t leaving.”

York put down his knife and fork and made a steeple of his fingers.

“For my own reasons, I want to be master of a steamboat. I want to travel the length of this great river, in comfort and privacy, not as passenger but as captain. I have a dream, a purpose. I seek friends and allies, and I have enemies, many enemies. The details are none of your concern. If you press me about them, I will tell you lies. Do not press me.” His eyes grew hard a moment, then softened as he smiled. “Your only interest need be my desire to own and command a steamboat, Captain. As you can tell, I am no riverman. I know nothing of steamboats, or the Mississippi, beyond what I have read in a few books and learned during the weeks I have spent in St. Louis. Obviously, I need an associate, someone who is familiar with the river and river people, someone who can manage the day-to-day operations of my boat, and leave me free to pursue my own purposes.

“This associate must have other qualities as well. He must be discreet, as I do not wish to have my behavior—which I admit to be sometimes peculiar—become the talk of the levee. He must be trustworthy, since I will give all management over into his hands. He must have courage. I do not want a weakling, or a superstitious man, or one who is overly religious. Are you a religious man, Captain?”

“No,” said Marsh. “Never cared for bible-thumpers, nor them for me.”

York smiled. “Pragmatic. I want a pragmatic man. I want a man who will concentrate on his own part of the business, and not ask too many questions of me. I value my privacy, and if sometimes my actions seem strange or arbitrary or capricious, I do not want them challenged. Do you understand my requirements?”

Marsh tugged thoughtfully on his beard. “And if I do?”

“We will become partners,” York said. “Let your lawyers and your clerks run your line. You will travel with me on the river. I will serve as captain. You can call yourself pilot, mate, co-captain, whatever you choose. The actual running of the boat I will leave to you. My orders will be infrequent, but when I do command, you will see to it that I am obeyed without question. I have friends who will travel with us, cabin passage, at no cost. I may see fit to give them positions on the boat, with such duties as I may deem fitting. You will not question these decisions. I may acquire other friends along the river, and bring them aboard as well. You will welcome them. If you can abide by such terms, Captain Marsh, we shall grow rich together and travel your river in ease and luxury.”

Abner Marsh laughed. “Well, maybe. But it ain’t my river, Mister York, and if you think we’re going to travel in luxury on the old Eli Reynolds, you’re going to be awful sore when you come on board. She’s a rackety old tub with some pretty poor accommodations, and most times she’s full of foreigners taking deck passage to one unlikely place or the other. I ain’t been on her in two years—old Cap’n Yoerger runs her for me now—but last time I rode her, she smelled pretty bad. You want luxury, you ought to see about buying into the Eclipse or the John Simonds.”

Joshua York sipped at his wine, and smiled. “I did not have the Eli Reynolds in mind, Captain Marsh.”

“She’s the only boat I got.”

York set down his wine. “Come,” he said, “let us settle up here. We can proceed up to my room, and discuss matters further.”

Marsh made a weak protest—the Planters’ House offered an excellent dessert menu, and he hated to pass it up. York insisted, however.

York’s room was a large, well-appointed suite, the best the hotel had to offer, and usually reserved for rich planters up from New Orleans. “Sit,” York said commandingly, gesturing Marsh to a large, comfortable chair in the sitting room. Marsh sat, while his host went into an inner chamber and returned a moment later, bearing a small iron-bound chest. He set it on a table and began to work the lock. “Come here,” he said, but Marsh had already risen to stand behind him. York threw back the lid.

“Gold,” Marsh said softly. He reached out and touched the coins, running them through his fingers, savoring the feel of the soft yellow metal, the gleam and the clatter of it. One coin he brought to his mouth and tasted. “Real enough,” he said, spitting. He chunked the coin back in the chest.

“Ten thousand dollars in twenty-dollar gold coins,” York said. “I have two other chests just like it, and letters of credit from banks in London, Philadelphia, and Rome for sums considerably larger. Accept my offer, Captain Marsh, and you shall have a second boat, one far grander than your Eli Reynolds. Or perhaps I should say that we shall have a second boat.” He smiled.

Abner Marsh had meant to turn down York’s offer. He needed the money bad enough, but he was a suspicious man with no use for mysteries, and York asked him to take too much on faith. The offer had sounded too good; Marsh was certain that danger lay hidden somewhere, and he would be the worse for it if he accepted. But now, staring at the color of York’s wealth, he felt his resolve weakening. “A new boat, you say?” he said weakly.

“Yes,” York replied, “and that is over and above the price I would pay you for a half-interest in your packet line.”

“How much . . .” Marsh began. His lips were dry. He licked them nervously. “How much are you willin’ to spend to build this new boat, Mister York?”

“How much is required?” York asked quietly.

Marsh took up a handful of gold coins, then let them rattle through his fingers back into the chest. The gleam of them, he thought, but all he said was, “You oughtn’t carry this much about with you, York. There’s scoundrels would kill you for one of them coins.”

“I can protect myself, Captain,” York said. Marsh saw the look in his eyes and felt cold. He pitied the robber who tried to take Joshua York’s gold.

“Will you take a walk with me? On the levee?”

“You haven’t given me my answer, Captain.”

“You’ll get your answer. Come first. Got something I want you to see.”

“Very well,” York said. He closed the lid of the chest, and the soft yellow gleam faded from the room, which suddenly seemed close and dim.

The night air was cool and moist. Their boots sent up echoes as they walked the dark, deserted streets, York with a limber grace and Marsh with heavy authority. York wore a loose pilot’s coat cut like a cape, and a tall old beaver hat that cast long shadows in the light of the half-moon. Marsh glared at the dark alleys between the bleak brick warehouses, and tried to present an aspect of solid, scowling strength sufficient to scare off ruffians.

The levee was crowded with steamboats, at least forty of them tied up to landing posts and wharfboats. Even at this hour all was not quiet. Huge stacks of freight threw black shadows in the moonlight, and they passed roustabouts lounging against crates and bales of hay, passing a bottle from hand to hand or smoking their cob pipes. Lights still burned in the cabin windows of a dozen or more boats. The Missouri packet Wyandotte was lit and building steam. They spied a man standing high up on the texas deck of one big side-wheel packet, looking down at them curiously. Abner Marsh led York past him, past the procession of darkened, silent steamers, their tall chimneys etched against the stars like a row of blackened trees with strange flowers on their tops.

Finally he stopped before a great ornate side-wheeler, freight piled high on her main deck, her stage raised against unwanted intruders as she nuzzled against her weathered old wharfboat. Even in the dimness of the half-moon the splendor of her was clear. No steamer on the levee was quite so big and proud.

“Yes?” Joshua York said quietly, respectfully. That might have decided it right there, Marsh thought later—the respect in his voice.

“That’s the Eclipse,” Marsh said. “See, her name is on the wheelhouse, there.” He jabbed with his stick. “Can you read it?”

“Quite well. I have excellent night vision. This is a special boat, then?”

“Hell yes, she’s special. She’s the Eclipse. Every goddamned man and boy on this river knows her. Old now—she was built back in ’52, five years ago. But she’s still grand. Cost $375,000, so they say, and worth all of it. There ain’t never been a bigger, fancier, more formid-a-bul boat than this one right here. I’ve studied her, taken passage on her. I know.” Marsh pointed. “She measures 365 feet by 40, and her grand saloon is 330 feet long, and you never seen nothin’ like it. Got a gold statue of Henry Clay at one end, and Andy Jackson at the other, the two of ’em glaring at each other the whole damn way. More crystal and silver and colored glass than the Planters’ House ever dreamed of, oil paintings, food like you ain’t never tasted, and mirrors—such mirrors. And all that’s nothin’ to her speed.

“Down below on the main deck she carries 15 boilers. Got an 11-foot stroke, I tell you, and there ain’t a boat on any river can run with her when Cap’n Sturgeon gets up her steam. She’s done eighteen miles an hour upstream, easy. Back in ’53, she set the record from New Orleans to Louisville. I know her time by heart. Four days, nine hours, thirty minutes, and she beat the goddamned A. L. Shotwell by fifty minutes, fast as the Shotwell is.” Marsh rounded to face York. “I hoped my Lady Liz would take the Eclipse some day, beat her time or race her head to head, but she never could of done it, I know that now. I was just foolin’ myself. I didn’t have the money it takes to build a boat that can take the Eclipse.

“You give me that money, Mister York, and you’ve got yourself a partner. There’s your answer, sir. You want half of Fevre River Packets, and a partner who runs things quiet and don’t ask you no questions ‘bout your business? Fine. Then you give me the money to build a steamboat like that.”

Joshua York stared at the big side-wheeler, serene and silent in the darkness, floating easily on the water, ready for all challengers. He turned to Abner Marsh with a smile on his lips and a dim flame in his dark eyes. “Done,” was all he said. And he extended his hand.

Marsh broke into a crooked, snaggle-toothed grin, wrapped York’s slim white hand within his own meaty paw, and squeezed. “Done, then,” he said loudly, and he brought all his massive strength to bear, squeezing and crushing, as he always did in business, to test the will and the courage of the men he dealt with. He squeezed until he saw the pain in their eyes.

But York’s eyes stayed clear, and his own hand clenched hard around Marsh’s with a strength that was surprising. Tighter and tighter it squeezed, and the muscles beneath that pale flesh coiled and corded like springs of iron, and Marsh swallowed hard and tried not to cry out.

York released his hand. “Come,” he said, clapping Marsh solidly across the shoulders and staggering him a bit. “We have plans to make.”

Recenzii

“A novel that will delight fans of both Stephen King and Mark Twain . . . darkly romantic, chilling and rousing by turns . . . a thundering success.”—Roger Zelazny

“An adventure into the heart of darkness that transcends even the most inventive vampire novels . . . Fevre Dream runs red with original, high adventure.”—Los Angeles Herald Examiner

“Stands alongside Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire as a revolutionary work.”—Rocky Mountain News

“Engaging and meaningful.”—The Washington Post Book World

“An adventure into the heart of darkness that transcends even the most inventive vampire novels . . . Fevre Dream runs red with original, high adventure.”—Los Angeles Herald Examiner

“Stands alongside Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire as a revolutionary work.”—Rocky Mountain News

“Engaging and meaningful.”—The Washington Post Book World