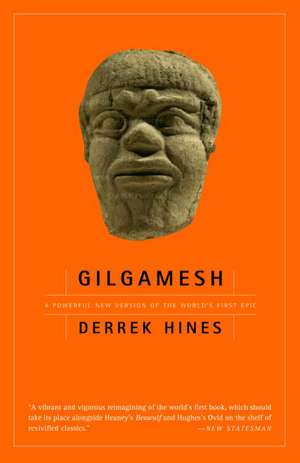

Gilgamesh

Autor Derrek Hinesen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 2004

Gilgamesh, the semi-divine ruler of Uruk, is a larger-than-life bully and abuser of his people. In order to tame the arrogant king, the gods create the wild and handsome Enkidu. But after Enkidu and Gilgamesh become fast friends, they defy the gods in a series of outsized adventures that brings Gilgamesh face to face with both loss and death itself. Hines energizes this timeless tale with vivid and electrifyingly modern images, from the goddess Ishtar cracking the sound barrier, to a battlefield nightmare of spectral snipers and exploding hand grenades, to the CAT-scan image of a dying friend. The themes of love and friendship, grief, despair, and hope had their first great expression in this story, and this dazzling new interpretation brings us into its thrall again.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 72.42 lei 43-57 zile | |

| Anchor Books – 30 sep 2004 | 75.15 lei 22-36 zile | |

| Bloomsbury Publishing – 30 ian 2007 | 72.42 lei 43-57 zile |

Preț: 75.15 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 113

Preț estimativ în valută:

14.38€ • 15.05$ • 11.90£

14.38€ • 15.05$ • 11.90£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 17-31 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400077335

ISBN-10: 1400077338

Pagini: 84

Dimensiuni: 134 x 206 x 6 mm

Greutate: 0.1 kg

Ediția:Anchor Books.

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 1400077338

Pagini: 84

Dimensiuni: 134 x 206 x 6 mm

Greutate: 0.1 kg

Ediția:Anchor Books.

Editura: Anchor Books

Notă biografică

Derrek Hines was born and raised in Canada and read Ancient Near Eastern Studies at university. He has won prizes in, among others, the National Poetry Competition and the Arvon Foundation International Competition, and has published two books of poetry. He lives on the Lizard Peninsula in Cornwall.

Extras

Beginnings

Here is Gilgamesh, king of Uruk:

two-thirds divine, a mummy's boy,

zeppelin ego, cock like a trip-hammer,

and solid chrome, no-prisoners arrogance.

Pulls women like beer rings.

Grunts when puzzled.

A bully. A jock. Perfecto. But in love? -

a moon-calf and worse, thoughtful.

Next, a one-off:

clay and lightning entangled by the gods

to create a strong-man from the wastelands

to curb Gilgamesh -- named Enkidu.

Sour electric fear, desert mirage at your throat,

strong enough to hold back the night,

so handsome he robs the world of horizon -

for no one's gaze lifts beyond him.

Gilgamesh and Enkidu stand

astride the threshold of history at Sumer.

Five thousand years,

Ishtar's skirts,

five thousand years are gathered aside

so we enter the view from Uruk's palace:

Euphrates' airy, fish-woven halls,

a sleep of reed beds, the eclat of date palms,

wind-glossed corn. And in the distance

desert -- the sun's loose gunpowder.

Green rolls up

and rasps along it like a tongue

wetting sandpaper.

Here and there,

jostling with the fast-forward business

on the quays, spiralling above the potter's wheel,

buoyed by the clatter of cafe gossip:

up-drafts of ideas, thermals of invention.

For the cut of every thought here

is new for our race, and tart with novelty.

Then look: footprints of the mind's bird

in its take-off scramble across wet clay tablets.

Writing!

It was also time

when, just as the lemon tree's greenroom

sweats with auditions for tomorrow's sun,

the world swelled with potential heroes.

Have there been two such

as Gilgamesh and Enkidu

who released our first imagination

to map the new interior spaces we still

scribble on the backs of envelopes, of lives?

They strode into deeds like furnaces

to flash off the husk of their humanity,

and emerged, purified of time.

Now like a burning-glass Enkidu's wildness

is focusing the people's discontent

into dust devils of rumour

that scour through the city.

The Trapper is sent out,

ordered to hire a temple prostitute,

'a garment of Ishtar'; lead her into the desert

to civilise Enkidu -- net him

to quell Gilgamesh.

Shamhat of the April Gate

What do we know of sacred harlots?

What's sacred that sweeps through our lives?

Enter Shamhat, who can be bought like a beer

from the stall outside the temple gate.

Take her then as the whole, hired

month of April, of the gods' Now;

not as equivalence but the month,

harlot as might be April;

Shamhat as might be a modern woman

slouched over a back-street bistro table

her breasts too small to shadow yet,

and in her bruises almost overdressed;

skinny enough to dilute

the whisky-neon dawn.

A cup of sleet, a grubby

two-cigarette mantra

against the ache of breaching

in her sex:

the month's raw, self-greasing tubers

forcing up into shoots

the sap's hot green ether.

And the drag-chute of Spring's afterbirth

nicked on the wind's thorn.

Cruel, cruellest and . . .

a rag of love-things in free fall

in her heart that shouldn't be here,

like a man

--like this one, the Trapper,

who draws her as the moon the slake-tide,

through the desert

to water Enkidu's lime-dry throat.

All the men who crutched her belly on bedsteads,

gorged her, ground her hips above the grave's

mattress, stand with her now.

'I am Shamhat.' She fingers Enkidu's tangled hair.

(A pro: her flashgun smile will develop

to red-eye, his lust-eye.)

You have seen a cottage by the sea,

white, lap-built against the spray,

paused in the lilt of dunes

like a skiff with feathered oars,

its darkness waiting for summer.

Then the shucking of winter shutters;

the abrupt gush and gulp of light

quenching a thirsting interior

like un-boarding an old fountain:

thus Enkidu's soul at Shamhat's touch.

And his sadness, suddenly aware of what he is,

a fumble of doubts and longings.

'I am Shamhat.

Part my gown and the keys at my girdle

that undo whore, undo mother, saint,

to reveal the eternal carcass tipped in the beauty

of the dunghill or the star-breeding towers in Orion.'

To Enkidu, who has known

no other woman, she is beautiful.

From the ruined face

the gentle voice, like a buddleia

flowering through a derelict factory's window.

His fingers, calloused by freedom,

struggle like netted birds

with the breathy sea-cotton of her layers

(O my first woman!):

the wonder and nuzzle of breasts,

the notch that baits men

as iron filings are drawn to fur a magnet.

Finally Shamhat gasped a full-throated

praise of male hydraulics,

entering her like the stiff shaduf

that lifts night's constellations off the river's face,

spilling wet star-seed into the splayed canals.

After seven nights of love,

as a man might,

Enkidu lost his understanding of animal speech.

But it was a fair trade.

The Meeting

Day

descends;

a hem (a garter?) now her thigh

eases

into the nevermore of dusk's entropy;

and she looks back over her shoulder,

up through the lush flip-book

of her farewells.

A line of crushed light remains above the horizon

as if the shutters on a jeweller's window

had jammed an inch shy of closing;

space enough

to allow Enkidu and Shamhat

to materialise before Uruk's gate.

Street urchins gawk; donkeys absorb.

A town guide peels from the shadows,

approaches, and falls back in awe.

Enkidu has come to strip Gilgamesh

of his right to taste the bride before the husband.

The foundry of his anger quakes and glows.

They push through the streets without torches;

Shamhat, three paces behind,

lights his way.

Enkidu is troubled, his anger flawed.

Doubt tears at certainty --

a risk the self-righteous must take --

for what he expects

he might not find.

But her? Watch her. She is changing,

uncloaking from a chrysalis of desert calico

that shimmers and wings to silk in her slipstream

a hundred feet into air

borrowed from Heaven.

The volume of her presence

soars beyond the audible;

she reveals herself like a female Odysseus

transfixing the suitors;

bursts from Penelope's weaving,

and with her swarm

the hungry threads of power.

She is no longer the 'garment of Ishtar'

but its very owner, striding down

the cat-walk of Uruk's high street

in the designer gowns of Paradise,

Ishtar's high priestess, Goddess incarnate;

so briefly glimpsed in passing,

the grace of her,

like snow touching warm ground.

Hip to hip, Shamhat and light,

part the darkness; of the two

she is the more radiant.

Enkidu sees none of this;

broods and stomps on.

Soft-mouthed as a gundog

dark retrieves these few sounds:

a clatter of supper plates,

the dry thresh, like a woman's stockings,

of palm fronds,

the rustle of moonlight, rinsing itself

up to its wrists in the river.

Across town, Gilgamesh

sets off to split a bride's veil

while the groom groans white with shame.

His right? Divine right, power right.

In reverse order.

Around him in the swelter-light

smuts off reed torches cling

to the sweating skin of his young bucks,

the town's jeunesse doree,

nervy as water splattered on hot oil;

too drunk for honour, but hoping

for woman-scraps from his table.

He has corrupted their worth

with his vanity, yet

they mime his airs, ape his swagger,

try on his used breath

to live second-hand,

hand-me-down time,

always in fear of that whetted anger,

half-drawn in his pride's sheath.

To him they are means.

Gilgamesh squats on Uruk's soul.

A messenger stands before the king,

his mouth working like a boated trout,

or a seer fresh out of prophecy.

Silence, a bolt, rigid in the throat.

Empty cups of faces turn to Gilgamesh.

Instantly everything is known --

the news clamps jump-cables to them

and throws a switch -- a current arcs and spits

between Gilgamesh here,

and Enkidu at the April Gate,

galvanising the town.

Talk dries in the cafes,

as when the soldiers of an occupation

enter a restaurant, and a coded silence

becomes speech. Where silence is language,

meaning is everywhere.

The people let fear think for them;

fear steals their thought and makes bold.

They watch Gilgamesh pass,

and chant under their breath,

like football fans from the terraces:

Dead. End. Cul-de-sac.

Dead. End. Cul-de-sac.

Still, as the heroes stumble into their roles,

there is someone, as always, disconnected --

someone whistling as he repairs a pot --

unmindful of the great events at his elbow

like the ploughman oblivious in Brueghel's

Fall of Icarus.

It is done; they accelerate towards each other

welded to Destiny's tram rails: two black cores

hungry for the other's light.

Juggernauts too wide for the narrow streets

they spew tall coxcombs of sparks

as they grind against the buildings.

They meet in the square, and stop.

Haste scissors off their clothes:

Enkidu's furs, drop and crouch;

the king's double silks (light blue, indigo,

like the two breezes off opposed seas

which ruffle the sheep's fleece on Hellespont)

faint to the ground --

both men now qualities of moonlight.

Sudden jostling in the crowd:

the fight is hijacked by the expectations

of spectacle -- paparazzi:

flashbulbs sun the moon aside

carving a tableau, a stark iconography

of function without emotion.

The contestants are burnished gold-leaf,

wetted crimson in the glare;

heraldic beasts on a carousel,

huge, stupid with encoded exhibition.

They topple into each other

like the Empire State and Chrysler buildings;

their hearts trapped in the elevators,

their minds locked in the blueprints

of testosterone flush and muscle.

Fierce, so saturated, dense with power, they are become

a gravity: voices and light bend nearing them.

They drain cities of energy from each other

and draw on more: distant Lakish dims,

Ur browns out . . .

Until, from behind the crowd, Shamhat speaks.

Only the wrestlers hear her voice,

200 cubic miles of summer storm, compressed,

compressed: -- it begins as

a wet finger rubbed around the rim of a wine glass;

increases to a whisper, gears up to a rumble

circling a bronze chamber in their heads --

faster -- until the words burst in their skulls:

THE GODS ORDAIN FRIENDSHIP.

Anger is reversed so violently

they are motion sick with the change

and the challenge of foreignness,

as when, in the uncertainty of abroad,

you find you are a question,

not the answer you thought yourself to be.

Backwards from the clinch, dream-escaping;

smile into eyes . . .

The crowd murmurs, restive with discontent.

A formula has been betrayed. The fight ends

not in justice as they expected:

Shamhat imposed the epiphany of recognition,

which is greater than justice and love.

But it is not resolution.

Gilgamesh takes one heady step, two;

living for the first time

for someone else.

Gilgamesh's Hymn to Morning

See, dawn breathes into . . . the flaws:

rumour behind bitumen,

false-dawn cock crow, current surge . . .

Dark's unstable touch-paper splutters

and launches the invention of

SUN -- gold vaporised at dew point

flash-plating the river's laid steel.

'O, great spinnaker of morning,

bellied by a wind

taller than the meadows of Orion,

that pulls into its cavitation thought --

the spindrift off the impossible --

the first draw of worked, imaginable space

that roils and oils and charms mind

into a downright love of it.

For is thought not the greatest mystery,

and imagination a metaphor

for its beauty and wonder?

'Come, my brother --

a broad jest of sunlight

clowns on the sills of day

just as we entertain the gods,

our doings like oar-prints

filling with the provinces of Heaven.

And all is written: Fate already chalked

on the lofting floor, the theorems of grace,

the tracings of wind's plumed assumption.

Lift your arms and sail.

'Listen: noon

evaporates from the water-clock;

noon, on the slack-clutched river

where light lists a degree, furls and crumples

like a xebec shrugging its sails off the wind.

This is honey time, Enkidu,

and we stand braced on the walls of Uruk

as at the kerb of dreams.

Let us tread them like gods,

for, my friend, such days are gifts,

victories over the immense indifference.

We will inhale this, our life's dawn

evaporating off a god's brow; grasp time by its scruff;

brave the entry-only land of the hero,

and not return: for once we've stepped into it,

the people never allow the hero

to be a part of them again.

There we are to capture for thought,

unmarked, stateless spaces in the mind,

and leave them outside the walls for mankind.'

Heroes. Consider, reader: heroes.

The whole idea waiting to abuse itself.

The modernist in us undercutting

everything to be said here,

with that taste for the corruption of the ideal,

the soured, smug edge of bankrupt irony

defending us from belief, that 'safety in derision'.

We can be ironical with the matter of the issue,

but not its spirit. That

inhales dawns.

The Humbaba Campaign

(A soldier's diary)

The councillors were dead against the madness --

a thousand miles to Lebanon for cedar

and squander the toff's precious Hooray Henrys

against Humbaba's troops . . .

But our lord Gilgamesh strutted and harangued:

shrivel-calves, rattle-scrotums,

fear's banquet, etc.

A dark voice, tar brushed over rust.

We clocked there was something rotten.

The while he was glancing at pretty-boy Enkidu.

You could see that edged glint in their eyes.

They got off on it,

egging each other on, dicks on the table.

Cedar for the temple doors, my ass.

It's glory's hard-on for those two,

and no mind for us. Bastards.

We were at ease in ranks for all this,

with no idea who Humbaba was; but the corporal

turned pale as blanco: 'He's the worst,

worse than watching your children burn alive

and surviving it. If we live after this show

we'll carry a hell even death won't ease.

He's a wizard, a quantum entanglement magus,

set by Enlil, Fate Maker,

to guard the Sacred Cedars in Lebanon.,

So, we figured, no snatch for medals in this caper.

A month now, desert-yomping in full kit.

Scorpion wind in the face, crotch rot, boils.

Not helped by our great King, who wakes each morning

from dreams like multiple car crashes --

a bloody Cassandra weeping catastrophe,

until Enkidu talks him round.

In the valley of the Bekaa under Mt Lebanon.

Easy soldiering with the ladies willing,

their legs spread wide as a peal of bells;

plenty of grub, and the zig of split-stone fences

snaking through terraced orchards,

apple and Eve ready.

Good, rolling chariot country.

The foothills. Our yeomanry

got stuck into Humbaba's lot this morning.

We watched them shake out

into order of battle, advancing at a stroll

up the meadow towards the forest

as they dressed to the right,

like a list of names justifying into columns

for the face of a war memorial.

Three hundred yards beyond return

the telegram-maker of enemy fire

scythed out from the tree-line,

and the ranks started to crumple.

Men dying into grass;

all those souls whistling past our heads,

homewards.

We supported the chariots today --

soft-shelled tanks on a leash,

desperate to harden with speed,

but forced to slow into single file though the woods,

soft again.

Everyone screwed up to pitch; the recruits

like twists of green gunpowder.

From the flank we watched the ambush's fusillade

sieve most of them to Hell

Here is Gilgamesh, king of Uruk:

two-thirds divine, a mummy's boy,

zeppelin ego, cock like a trip-hammer,

and solid chrome, no-prisoners arrogance.

Pulls women like beer rings.

Grunts when puzzled.

A bully. A jock. Perfecto. But in love? -

a moon-calf and worse, thoughtful.

Next, a one-off:

clay and lightning entangled by the gods

to create a strong-man from the wastelands

to curb Gilgamesh -- named Enkidu.

Sour electric fear, desert mirage at your throat,

strong enough to hold back the night,

so handsome he robs the world of horizon -

for no one's gaze lifts beyond him.

Gilgamesh and Enkidu stand

astride the threshold of history at Sumer.

Five thousand years,

Ishtar's skirts,

five thousand years are gathered aside

so we enter the view from Uruk's palace:

Euphrates' airy, fish-woven halls,

a sleep of reed beds, the eclat of date palms,

wind-glossed corn. And in the distance

desert -- the sun's loose gunpowder.

Green rolls up

and rasps along it like a tongue

wetting sandpaper.

Here and there,

jostling with the fast-forward business

on the quays, spiralling above the potter's wheel,

buoyed by the clatter of cafe gossip:

up-drafts of ideas, thermals of invention.

For the cut of every thought here

is new for our race, and tart with novelty.

Then look: footprints of the mind's bird

in its take-off scramble across wet clay tablets.

Writing!

It was also time

when, just as the lemon tree's greenroom

sweats with auditions for tomorrow's sun,

the world swelled with potential heroes.

Have there been two such

as Gilgamesh and Enkidu

who released our first imagination

to map the new interior spaces we still

scribble on the backs of envelopes, of lives?

They strode into deeds like furnaces

to flash off the husk of their humanity,

and emerged, purified of time.

Now like a burning-glass Enkidu's wildness

is focusing the people's discontent

into dust devils of rumour

that scour through the city.

The Trapper is sent out,

ordered to hire a temple prostitute,

'a garment of Ishtar'; lead her into the desert

to civilise Enkidu -- net him

to quell Gilgamesh.

Shamhat of the April Gate

What do we know of sacred harlots?

What's sacred that sweeps through our lives?

Enter Shamhat, who can be bought like a beer

from the stall outside the temple gate.

Take her then as the whole, hired

month of April, of the gods' Now;

not as equivalence but the month,

harlot as might be April;

Shamhat as might be a modern woman

slouched over a back-street bistro table

her breasts too small to shadow yet,

and in her bruises almost overdressed;

skinny enough to dilute

the whisky-neon dawn.

A cup of sleet, a grubby

two-cigarette mantra

against the ache of breaching

in her sex:

the month's raw, self-greasing tubers

forcing up into shoots

the sap's hot green ether.

And the drag-chute of Spring's afterbirth

nicked on the wind's thorn.

Cruel, cruellest and . . .

a rag of love-things in free fall

in her heart that shouldn't be here,

like a man

--like this one, the Trapper,

who draws her as the moon the slake-tide,

through the desert

to water Enkidu's lime-dry throat.

All the men who crutched her belly on bedsteads,

gorged her, ground her hips above the grave's

mattress, stand with her now.

'I am Shamhat.' She fingers Enkidu's tangled hair.

(A pro: her flashgun smile will develop

to red-eye, his lust-eye.)

You have seen a cottage by the sea,

white, lap-built against the spray,

paused in the lilt of dunes

like a skiff with feathered oars,

its darkness waiting for summer.

Then the shucking of winter shutters;

the abrupt gush and gulp of light

quenching a thirsting interior

like un-boarding an old fountain:

thus Enkidu's soul at Shamhat's touch.

And his sadness, suddenly aware of what he is,

a fumble of doubts and longings.

'I am Shamhat.

Part my gown and the keys at my girdle

that undo whore, undo mother, saint,

to reveal the eternal carcass tipped in the beauty

of the dunghill or the star-breeding towers in Orion.'

To Enkidu, who has known

no other woman, she is beautiful.

From the ruined face

the gentle voice, like a buddleia

flowering through a derelict factory's window.

His fingers, calloused by freedom,

struggle like netted birds

with the breathy sea-cotton of her layers

(O my first woman!):

the wonder and nuzzle of breasts,

the notch that baits men

as iron filings are drawn to fur a magnet.

Finally Shamhat gasped a full-throated

praise of male hydraulics,

entering her like the stiff shaduf

that lifts night's constellations off the river's face,

spilling wet star-seed into the splayed canals.

After seven nights of love,

as a man might,

Enkidu lost his understanding of animal speech.

But it was a fair trade.

The Meeting

Day

descends;

a hem (a garter?) now her thigh

eases

into the nevermore of dusk's entropy;

and she looks back over her shoulder,

up through the lush flip-book

of her farewells.

A line of crushed light remains above the horizon

as if the shutters on a jeweller's window

had jammed an inch shy of closing;

space enough

to allow Enkidu and Shamhat

to materialise before Uruk's gate.

Street urchins gawk; donkeys absorb.

A town guide peels from the shadows,

approaches, and falls back in awe.

Enkidu has come to strip Gilgamesh

of his right to taste the bride before the husband.

The foundry of his anger quakes and glows.

They push through the streets without torches;

Shamhat, three paces behind,

lights his way.

Enkidu is troubled, his anger flawed.

Doubt tears at certainty --

a risk the self-righteous must take --

for what he expects

he might not find.

But her? Watch her. She is changing,

uncloaking from a chrysalis of desert calico

that shimmers and wings to silk in her slipstream

a hundred feet into air

borrowed from Heaven.

The volume of her presence

soars beyond the audible;

she reveals herself like a female Odysseus

transfixing the suitors;

bursts from Penelope's weaving,

and with her swarm

the hungry threads of power.

She is no longer the 'garment of Ishtar'

but its very owner, striding down

the cat-walk of Uruk's high street

in the designer gowns of Paradise,

Ishtar's high priestess, Goddess incarnate;

so briefly glimpsed in passing,

the grace of her,

like snow touching warm ground.

Hip to hip, Shamhat and light,

part the darkness; of the two

she is the more radiant.

Enkidu sees none of this;

broods and stomps on.

Soft-mouthed as a gundog

dark retrieves these few sounds:

a clatter of supper plates,

the dry thresh, like a woman's stockings,

of palm fronds,

the rustle of moonlight, rinsing itself

up to its wrists in the river.

Across town, Gilgamesh

sets off to split a bride's veil

while the groom groans white with shame.

His right? Divine right, power right.

In reverse order.

Around him in the swelter-light

smuts off reed torches cling

to the sweating skin of his young bucks,

the town's jeunesse doree,

nervy as water splattered on hot oil;

too drunk for honour, but hoping

for woman-scraps from his table.

He has corrupted their worth

with his vanity, yet

they mime his airs, ape his swagger,

try on his used breath

to live second-hand,

hand-me-down time,

always in fear of that whetted anger,

half-drawn in his pride's sheath.

To him they are means.

Gilgamesh squats on Uruk's soul.

A messenger stands before the king,

his mouth working like a boated trout,

or a seer fresh out of prophecy.

Silence, a bolt, rigid in the throat.

Empty cups of faces turn to Gilgamesh.

Instantly everything is known --

the news clamps jump-cables to them

and throws a switch -- a current arcs and spits

between Gilgamesh here,

and Enkidu at the April Gate,

galvanising the town.

Talk dries in the cafes,

as when the soldiers of an occupation

enter a restaurant, and a coded silence

becomes speech. Where silence is language,

meaning is everywhere.

The people let fear think for them;

fear steals their thought and makes bold.

They watch Gilgamesh pass,

and chant under their breath,

like football fans from the terraces:

Dead. End. Cul-de-sac.

Dead. End. Cul-de-sac.

Still, as the heroes stumble into their roles,

there is someone, as always, disconnected --

someone whistling as he repairs a pot --

unmindful of the great events at his elbow

like the ploughman oblivious in Brueghel's

Fall of Icarus.

It is done; they accelerate towards each other

welded to Destiny's tram rails: two black cores

hungry for the other's light.

Juggernauts too wide for the narrow streets

they spew tall coxcombs of sparks

as they grind against the buildings.

They meet in the square, and stop.

Haste scissors off their clothes:

Enkidu's furs, drop and crouch;

the king's double silks (light blue, indigo,

like the two breezes off opposed seas

which ruffle the sheep's fleece on Hellespont)

faint to the ground --

both men now qualities of moonlight.

Sudden jostling in the crowd:

the fight is hijacked by the expectations

of spectacle -- paparazzi:

flashbulbs sun the moon aside

carving a tableau, a stark iconography

of function without emotion.

The contestants are burnished gold-leaf,

wetted crimson in the glare;

heraldic beasts on a carousel,

huge, stupid with encoded exhibition.

They topple into each other

like the Empire State and Chrysler buildings;

their hearts trapped in the elevators,

their minds locked in the blueprints

of testosterone flush and muscle.

Fierce, so saturated, dense with power, they are become

a gravity: voices and light bend nearing them.

They drain cities of energy from each other

and draw on more: distant Lakish dims,

Ur browns out . . .

Until, from behind the crowd, Shamhat speaks.

Only the wrestlers hear her voice,

200 cubic miles of summer storm, compressed,

compressed: -- it begins as

a wet finger rubbed around the rim of a wine glass;

increases to a whisper, gears up to a rumble

circling a bronze chamber in their heads --

faster -- until the words burst in their skulls:

THE GODS ORDAIN FRIENDSHIP.

Anger is reversed so violently

they are motion sick with the change

and the challenge of foreignness,

as when, in the uncertainty of abroad,

you find you are a question,

not the answer you thought yourself to be.

Backwards from the clinch, dream-escaping;

smile into eyes . . .

The crowd murmurs, restive with discontent.

A formula has been betrayed. The fight ends

not in justice as they expected:

Shamhat imposed the epiphany of recognition,

which is greater than justice and love.

But it is not resolution.

Gilgamesh takes one heady step, two;

living for the first time

for someone else.

Gilgamesh's Hymn to Morning

See, dawn breathes into . . . the flaws:

rumour behind bitumen,

false-dawn cock crow, current surge . . .

Dark's unstable touch-paper splutters

and launches the invention of

SUN -- gold vaporised at dew point

flash-plating the river's laid steel.

'O, great spinnaker of morning,

bellied by a wind

taller than the meadows of Orion,

that pulls into its cavitation thought --

the spindrift off the impossible --

the first draw of worked, imaginable space

that roils and oils and charms mind

into a downright love of it.

For is thought not the greatest mystery,

and imagination a metaphor

for its beauty and wonder?

'Come, my brother --

a broad jest of sunlight

clowns on the sills of day

just as we entertain the gods,

our doings like oar-prints

filling with the provinces of Heaven.

And all is written: Fate already chalked

on the lofting floor, the theorems of grace,

the tracings of wind's plumed assumption.

Lift your arms and sail.

'Listen: noon

evaporates from the water-clock;

noon, on the slack-clutched river

where light lists a degree, furls and crumples

like a xebec shrugging its sails off the wind.

This is honey time, Enkidu,

and we stand braced on the walls of Uruk

as at the kerb of dreams.

Let us tread them like gods,

for, my friend, such days are gifts,

victories over the immense indifference.

We will inhale this, our life's dawn

evaporating off a god's brow; grasp time by its scruff;

brave the entry-only land of the hero,

and not return: for once we've stepped into it,

the people never allow the hero

to be a part of them again.

There we are to capture for thought,

unmarked, stateless spaces in the mind,

and leave them outside the walls for mankind.'

Heroes. Consider, reader: heroes.

The whole idea waiting to abuse itself.

The modernist in us undercutting

everything to be said here,

with that taste for the corruption of the ideal,

the soured, smug edge of bankrupt irony

defending us from belief, that 'safety in derision'.

We can be ironical with the matter of the issue,

but not its spirit. That

inhales dawns.

The Humbaba Campaign

(A soldier's diary)

The councillors were dead against the madness --

a thousand miles to Lebanon for cedar

and squander the toff's precious Hooray Henrys

against Humbaba's troops . . .

But our lord Gilgamesh strutted and harangued:

shrivel-calves, rattle-scrotums,

fear's banquet, etc.

A dark voice, tar brushed over rust.

We clocked there was something rotten.

The while he was glancing at pretty-boy Enkidu.

You could see that edged glint in their eyes.

They got off on it,

egging each other on, dicks on the table.

Cedar for the temple doors, my ass.

It's glory's hard-on for those two,

and no mind for us. Bastards.

We were at ease in ranks for all this,

with no idea who Humbaba was; but the corporal

turned pale as blanco: 'He's the worst,

worse than watching your children burn alive

and surviving it. If we live after this show

we'll carry a hell even death won't ease.

He's a wizard, a quantum entanglement magus,

set by Enlil, Fate Maker,

to guard the Sacred Cedars in Lebanon.,

So, we figured, no snatch for medals in this caper.

A month now, desert-yomping in full kit.

Scorpion wind in the face, crotch rot, boils.

Not helped by our great King, who wakes each morning

from dreams like multiple car crashes --

a bloody Cassandra weeping catastrophe,

until Enkidu talks him round.

In the valley of the Bekaa under Mt Lebanon.

Easy soldiering with the ladies willing,

their legs spread wide as a peal of bells;

plenty of grub, and the zig of split-stone fences

snaking through terraced orchards,

apple and Eve ready.

Good, rolling chariot country.

The foothills. Our yeomanry

got stuck into Humbaba's lot this morning.

We watched them shake out

into order of battle, advancing at a stroll

up the meadow towards the forest

as they dressed to the right,

like a list of names justifying into columns

for the face of a war memorial.

Three hundred yards beyond return

the telegram-maker of enemy fire

scythed out from the tree-line,

and the ranks started to crumple.

Men dying into grass;

all those souls whistling past our heads,

homewards.

We supported the chariots today --

soft-shelled tanks on a leash,

desperate to harden with speed,

but forced to slow into single file though the woods,

soft again.

Everyone screwed up to pitch; the recruits

like twists of green gunpowder.

From the flank we watched the ambush's fusillade

sieve most of them to Hell

Recenzii

“A vibrant and vigorous reimagining of the world’s first book, which should take its place alongside Heaney’s Beowulf and Hughes’s Ovid on the shelf of revivified classics.” —The New Statesman

“A brilliant version of an ancient tale; replete with humour, pathos, drama, and much more." –The Telegraph

"Derrek Hines makes Gilgamesh exciting." –The Guardian

"Hines's distinctive mode–part surreal, part cinematic–combines the concentration of lyric poetry with the narrative compulsion and fluency of an adventure story." –Times Literary Supplement

"Hines's energetic metaphors and nimble wit revivify the thrill of a very old tale."

–Times (London)

“An evocative lyric journey through the Mesopotamian story, glittering with Hines’ own fresh images.” —The Financial Times

“A sparkling poetic vision.” —The Oxford Times

“Impressive, consistent . . . packed with good things.” —Christopher Logue

“I read this version with great interest and admiration. It has real energy and drive with some splendidly interesting images. I was held throughout.” —Ian Hamilton

“A superb achievement. The cinematic swoops, that terrific, loss-haunted elegy, absolutely packed with reverberating phrases. . . . It is not only a rendering of the poem but a brilliant, vital contemporary commentary on it.” —Paul Newman, editor, Abraxis

“A brilliant version of an ancient tale; replete with humour, pathos, drama, and much more." –The Telegraph

"Derrek Hines makes Gilgamesh exciting." –The Guardian

"Hines's distinctive mode–part surreal, part cinematic–combines the concentration of lyric poetry with the narrative compulsion and fluency of an adventure story." –Times Literary Supplement

"Hines's energetic metaphors and nimble wit revivify the thrill of a very old tale."

–Times (London)

“An evocative lyric journey through the Mesopotamian story, glittering with Hines’ own fresh images.” —The Financial Times

“A sparkling poetic vision.” —The Oxford Times

“Impressive, consistent . . . packed with good things.” —Christopher Logue

“I read this version with great interest and admiration. It has real energy and drive with some splendidly interesting images. I was held throughout.” —Ian Hamilton

“A superb achievement. The cinematic swoops, that terrific, loss-haunted elegy, absolutely packed with reverberating phrases. . . . It is not only a rendering of the poem but a brilliant, vital contemporary commentary on it.” —Paul Newman, editor, Abraxis