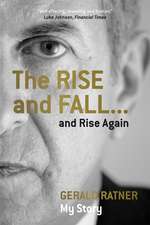

Going Hungry: Writers on Desire, Self-Denial, and Overcoming Anorexia

Autor Kate Tayloren Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 aug 2008 – vârsta de la 16 până la 18 ani

With essays by Priscilla Becker, Francesca Lia Block, Maya Browne, Jennifer Egan, Clara Elliot, Amanda Fortini, Louise Glück, Latria Graham, Francine du Plessix Gray, Trisha Gura, Sarah Haight, Lisa Halliday, Elizabeth Kadetsky, Maura Kelly, Ilana Kurshan, Joyce Maynard, John Nolan, Rudy Ruiz, and Kate Taylor.

www.anchorbooks.com

www.goinghungry.com

Preț: 117.58 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 176

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.50€ • 23.55$ • 18.62£

22.50€ • 23.55$ • 18.62£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 05-19 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307278340

ISBN-10: 0307278344

Pagini: 306

Dimensiuni: 130 x 201 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 0307278344

Pagini: 306

Dimensiuni: 130 x 201 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

Notă biografică

Kate Taylor is a culture reporter at the New York Sun; her writing has also appeared in Slate and the New Yorker. She lives in New York.

Extras

HUNGER STRIKING

Maura Kelly

For a few weeks during the summer before high school, I resembled one of the catwalkers from the pages of The New York Times’ s style supplement, which covered my bedroom wall in a Scotch Tape collage. It wasn’t my face that was like theirs, or my clothes. (My usual look was a pocket T-shirt and cutoff jeans shorts, while the glossy girls wore kimono dresses, peacock-feather hats, and short pointy boots like white cockatoos.) It was my body. My stomach had caved in. My hip bones flared like wings. My legs met only at the knees and ankles: There was a teardrop-shaped gap between my thighs, and another between my calves. Knobby bones protruded dangerously from my wrists and elbows. My arms seemed longer, and from the ends of them, my enormous hands flopped, awkward as a marionette’s. I was barely thirteen, five feet and five inches tall, and down to 90 pounds from 110.

My transformation thrilled me.

Still, I wasn’t quite thin enough. So I kept going, and the changes became even more exciting. The colored hairbands I kept around my wrist got so loose that I could easily slide them up to my elbow. If I pressed my hand around the part of my arm where the shoulder met the biceps, I could touch my thumb with the pad of my ring finger. I could also put both hands around my thigh and touch thumb to thumb, pinky to pinky. I’d measure myself like that again and again when no one was watching, usually in the bathroom stall at school; it reassured me that I hadn’t somehow gotten fatter in the hours since I’d been on the scale that morning. My ribs became so visible that I could count them not only from the front but also, if I used two mirrors, from the back as they curved out from the knotted rope of my spine.

I began to resemble someone else tacked up in my room: Jesus Christ.

Now there was an icon. There was a guy who knew something about style: the original long-haired, emaciated, rock- star type. But it wasn’t just Jesus’ body that I admired; it was his suffering, too, and the way it made people love him. Jesus had been my first role model, and I still respected the guy, even if I was a full-fledged nonbeliever by then. As he hung from the crucifix my dead mother had positioned over my dresser, Jesus inspired me—with his skeleton hanging out of his skin, his blood dripping from his crown of thorns, and his face turned imploringly upward in the moment before his death as he said, “My God, my Father, why have you forsaken me?”

I knew how Jesus felt, asking that question. When my mother died of cancer the summer I turned eight, I felt pretty forsaken myself. I had no idea she was dying. I knew she was sick, of course, but my parents told my sister and me that she just had a very bad cold, kind of like chicken pox, except the bumps were inside.

Her illness replaced me—the baby—and became the most important thing in my mother’s life. Before she’d gotten sick, she loved everything I did, whether it was the Little Tea- pot dance, or one of my typically opinionated comments (“I don’t want to grow up to be like you, Mommy, always driv- ing my kids around”), or just burying my face in her neck to cry. But after she was diagnosed, I wasn’t as easy to love; at least, it was harder to get her full attention. For the last four years of her life, she spent one week out of every month in the hospital getting chemotherapy—a word I could say but not define—and when she was home, she spent a lot of time in bed with the curtains drawn. She didn’t like it when I was loud, and sometimes she was too weak to even kiss me back after I pressed my lips against her cheek. Her head would just stay on the pillow.

Whenever she wasn’t feeling well, I tried to leave her alone. I tried not to need anything from her. I became self-conscious: worried about what effect my actions would have, and aware of my own presence in a room.

Everyone—my parents, my other relatives, and the priests and nuns we knew, including my uncle Father Jimmy—told me that my mother might get better if I was a very good girl and asked God to help us. I would have done anything to get my mother back the way she used to be, so I prayed. I also sang at church with my family on Sunday mornings, as loudly and clearly as I could, because the pastor said singing was praising God twice. (I just hoped that Juan-Juan Santiago, who sat across the aisle from us with his parents and little brother, wouldn’t notice what a geek I was.) One of my favorite hymns was in praise of lasagna—or so I thought, till my mother caught on to what I was saying, and explained that the word was actually hosana, which means, roughly, “God is great.” And to show the devil I hated him, I’d jump up and down in the grass—as close to Hell as I could get—until I’d exhausted myself. Then I’d lie on the ground, blowing kisses up to the angels. Everyone said God was always watching over me, which was nice, especially since my mother wasn’t anymore. My growing love for God, and His for me, was helping to fill the hole my mother was making. I’d picture Him with the big white beard, in a white robe, in a white throne that floated on the clouds, smiling down at me, and I’d smile back.

It wasn’t just through physical actions that I tried to make myself God’s favorite; there were also the things I’d do in my head. During Mass, I’d recite the Penitential Rite with the rest of the congregation: “I have sinned through my own fault, in my thoughts and in my words, in what I have done, and in what I have failed to do.” I’d feel gravely sorry about all my transgressions: how I’d once again stuffed myself with chocolate-chip cookies and marshmallows in the morning, before my parents woke up; how I’d punched my sister in the rear end; how I’d stuck my tongue out at my father when he wasn’t watching. I’d pinch myself once on the thigh for each sin, and resolve to become a better person. I knew how important it was to God that my head be as pure as my actions, so whenever I had bad thoughts—like how much I hated the new Indian kid in our class, Raj, because he smelled funny and was hairy—I’d start to pray, trying to push the evil away. I was trying so hard and God loomed so large in my mind (even larger than Juan-Juan) that I was confident I was one of His favorites.

But I started to wonder if that was true after my mother died that August, twenty days after my birthday. I was so unprepared that when my father first told me I laughed. “Really, when can we pick her up from the hospital?” I said. “Tell me.” He only stared at me. “Tell me,” I insisted. Still, he didn’t speak, and my sister, sitting in his lap, started to cry. That unsettled me enough that I went to get a closer look at my father. When tears started coming down his face, too, I was terrified. Something had to be seriously wrong, but I was too young—or too shocked—to really understand what was going on.

I didn’t give up the hope that my mother might somehow pop out of her coffin until I first saw her in the wooden box at the wake. That’s when I started to appreciate what being dead meant. The rosy blush my mother usually wore had been replaced by two heavy circles of red on her cheeks; instead of her favorite mauve lipstick, there was a brown smear on her mouth. I could see the pores on her face as clearly as if they’d been made with a pencil. Her skin was thick and hard and unyielding under my fingertips, like football leather. I realized there was no way that body was going to sit up and say “Surprise!” and then reach out to tickle me under the arms. I climbed up on the kneeler and kissed her, maybe because I still had fairy-tale hopes about what that could do for a dead person. But it didn’t make any difference. Those rubber lips took away any doubt I had left—about her death, anyway.

But suddenly, everything else in my life was thrown into question. It wasn’t only my mother who was gone: It was my understanding of the universe, of myself, of God, and even of my own father. Overwhelmed by his grief, bills, and the responsibility of trying to raise two girls alone, he became a stranger to me: moody, unpredictable, and frightening—the big villain in my life. Suddenly, we were shouting at each other so much that I believed it when the first nanny we had after my mother died, a young woman from northern Ireland named Marie, told me again and again my father didn’t love me. Every night, I waited for him to come home with the worst longing and the most terrible fear, wondering if he would prove Marie right one more time.

I couldn’t count on my so-called Heavenly Father anymore, either, considering I was convinced that He’d killed my mother to punish me. (He couldn’t have had it out for anyone else in my family, I figured, since my connection to Him was more intense than theirs, for better and for worse.) What I couldn’t figure out was why God was so angry with me. In what way had I offended Him? I kept going over and over everything that I’d done and thought in the weeks leading up to my mother’s death, the way a guilty lover will after a suicide, and though there were all the usual little bad things—sneaking cookies, punching my sister, hating Raj—there wasn’t anything new and outstandingly wicked that would explain God’s act of vengeance against me. Also, I was nowhere near as bad as some of the other kids in my town, especially not the ones from the public middle school, who smoked cigarettes on the railroad tracks behind my house, or had sex in the old band shell at Memorial Park, or did drugs in their cars in the Burger King parking lot.

Since it seemed obvious I couldn’t have done anything to bring on the wrath of God, I figured there must be something inherently wrong with me. Did He hate me because I wasn’t as good in my heart as I’d thought? Probably. And maybe my mother hadn’t really loved me, either. Why else would she have left without even saying good-bye, or that she’d miss me?

Those kinds of questions were hard to face, so eventually I convinced myself, as best as I could, that the problem wasn’t with me but with Catholicism. I’d tried so hard to follow the rules, in my actions and my thoughts, and what had it got- ten me but a dead mother? I didn’t want to live that way anymore. But I did want something to believe in—a system that was more transparent and would yield visible results. I wanted proof that I was good.

Dieting eventually became a replacement religion for me, with its own set of commandments and rituals. It became a way for me to be my own god and my own creation—Pygmalion and Galatea in the same human body. It became a perverse method for mothering myself: I structured my meals, my days, and my thoughts around it. Dieting became my internal compass. It became the new thing for me to be the best at. I was so devoted that I was practically ready to give up my life for it.

But when I first started losing weight, toward the end of eighth grade, I had no idea I would become a fanatic. It was far more simple than that. All I wanted was to look like I had at the beginning of the school year, before my abdomen began to protrude under the band of my Hanes underwear. Though I realize now it was just an early sign of puberty, that curve disgusted me. I felt like a dog in heat, with it poking out of me. I had to be out of control if I’d let my body turn into that. And I figured if I lost five pounds—just five—my stomach would be flat again. But as it turned out, I had to drop closer to fifteen pounds before the curve disappeared, and once I got that far, I couldn’t stop. I was addicted to losing.

Part of the appeal was how much dieting simplified my life. Nothing else mattered but the numbers: how many calories I’d eaten that day; how many pounds I’d lost in the last week, or month; how many leg lifts or push-ups I’d do that night. I’d add, subtract, and double-check constantly. I felt like I was moving toward some great new salvation. Instead of praying when I felt scared or guilty or lonely, I’d turn to the numbers, like my grandmother to her wooden rosary beads, and they’d calm me down.

My head became so full of equations and plans about what I would eat and what exercises I would do that I didn’t have room for much else. I stopped worrying about not having any boobs even though every other girl in my class had them. I stopped caring about how all the boys, including Juan-Juan, had a crush on my best friend, Catherine McMurtry. I stopped feeling guilty about all the games of Truth or Dare and Seven Minutes in Heaven I’d played, and how it made me feel weird and gross but also excited whenever there was a boy’s tongue in my mouth. I stopped thinking about all those times Marie had told me that my father didn’t love me. My calculations not only filled up all the empty spaces in my head; they also helped me determine the value of my self. On any day that I’d eaten less, worked out longer, or lost more, it didn’t mean I was good, but at least I wasn’t bad.

The most important number, though, was one I had no idea how to determine: the weight I’d have to be to let myself stop, the weight that would mean I was finally good enough. In the very beginning, I thought it would be 105. Then it became one hundred. Ninety-five. Ninety. By the time I weighed eighty-five, I started to wonder if I’d ever be able to predict what the right weight was. Maybe I wouldn’t know until I reached it.

That summer before high school, when the dieting fever really started to take hold, I was fighting more than ever with my father, an Irish immigrant who made his living paving people’s driveways and laying concrete. Maybe part of the problem was that there was no other adult in the house to help keep us in our corners: My father hadn’t (and still hasn’t) remarried, and we were between housekeepers at that point. He hired and fired sixteen different women before I got to college, but never before I got attached to them; each one of them seemed like some kind of mother to me.

Our door started to revolve after he kicked out Marie, who’d been with us for four years. She’d become slowly obsessed with my father, and eventually demanded that he marry her, though they’d never been romantically involved. She pleaded with him, saying that she was already acting like a mother to my sister and me; why not make her role official?

My father turned her down. One night shortly after the rejection, Marie pulled a huge knife out of the kitchen drawer and threatened to kill herself with it. I grabbed the cleaver away from her; my father ordered her out of the house, and we never saw her again, though for years she prank-called our house and one time even phoned Catherine McMurtry’s house, looking for me.

It wasn’t a coincidence that my obsession with dieting started soon after my father fired Marie. Screwed up as she was, she’d been a temporary stay against the confusion that ensued after my mother was gone. In the four years that she’d been with us, I’d come to depend on her, especially because I didn’t feel like I could depend on my father anymore. It never occurred to me to ask him if Marie was right all those times she said he didn’t love me; it seemed obvious he didn’t. After all, I apparently had a special talent for saying things that would infuriate him so much that he’d give me the silent treatment for days, even weeks. During those periods, he’d do everything he could to avoid looking at me, even keeping his head down if we were in the kitchen together.

Often our arguments would start over things in the news. My father was a conservative then, despite the fact that he also subscribed to The New York Times, whereas I was a born liberal, despite the fact that I’d represented Ronald Reagan in some faux presidential debate we’d had at school. I would read the Week in Review section every Sunday so I’d have ammunition when my father started in about something.

That summer, abortion made the headlines. (justices uphold rights by narrow vote, The New York Times said, after the Supreme Court ruled against a Pennsylvania anti-abortion law.) The topic was big in our kitchen, too. We’d get into it after my father arrived home, as the three of us were sitting down to a dinner I’d made. I always volunteered to cook whenever no one was on the payroll. My sister wasn’t any good at it—she’d once tried to boil spaghetti without put- ting any water in the pot. Besides, I thought my father would like me better if I took on some adult responsibilities. Because the weather was warm and we didn’t have air-conditioning, my father would preside at the head of the table wearing only his tar-blackened jeans and his mustard yellow work boots, in all his muscled bulk, smelling of sour sweat. His huge biceps always looked flexed even when they weren’t, and though his pecs had gotten slightly flaccid with middle age, they were still powerful. His torso and arms were evenly burned the same leathery brown color—no “farmer’s tan” for him—because he liked to take his shirt off in the sun when he was working.

Who knows exactly how our “discussions” would start, but soon enough, I’d swallow the instant rice I had in my mouth so I could say, “I just think a woman should be able to do whatever she wants with her body, is all. It seems pretty obvious to me.”

My father would raise his caterpillar eyebrows at me, and his face would twist from disbelief to disparagement to rage, and I knew things were about to get absurd.

“ ‘Whatever she wants with her body’—oh yeah?” He’d pound his Heineken bottle on the table. “So if you wanted to jump off a bridge, I should let you do that?”

“Wait—what?” Realizing my paper napkin had fallen to the floor, I’d grab another out of the wooden holder in the middle of the table so I could have something to hold on to. “I didn’t say anything about jumping off a bridge. Besides, suicide is totally different from abortion. There’s no law against it, I don’t think. I mean, no one really cares what you do to yourself—”

“So what are you saying? I should let you kill yourself?”

I felt outrage like a stab in my chest. “What?” I’d glance over at my sister, hoping she would at least roll her eyes at me—that she would give me some sign I wasn’t losing my mind—but she would refuse to look up from the wilted heap of green beans on her plate.

“You heard me,” he said.

“Of course you shouldn’t let me kill myself.”

My father would point his knife at me. “But it’s okay to kill babies?”

“This is crazy. First of all, we don’t even know when they become alive!” I’d slam my own fist on the table, and the milk in my glass would jump.

My father would drop his utensils onto his plate with a clatter and glare at me. “You just watch your step now. Just watch your step.”

I’d try to calm down. “All right, look. All I’m saying is a woman shouldn’t be forced to ruin her life just because—”

“Ruin her life? Well, isn’t that something. Isn’t that something. What if your mother thought you were going to ruin her life—did that ever occur to you?”

“That’s totally different. Isn’t it? It’s not like you guys were so poor you didn’t want to have me. Right? Right?”

He wouldn’t answer me directly. “Did you know that when your sister was born, they weren’t going to let me take her or your mother out of the hospital? I had no insurance. I didn’t have the money to pay the bill. I told them, ‘You goddamn better let me take them out—that’s my wife and my baby daughter we’re talking about.’ Did you know that?”

I did know. He’d told me a thousand times. But I wished he’d get back to my question.

Instead, he’d go on. “Where would you be now if your mother had gotten an abortion? You ever think of that?”

“That’s beside the point. All I’m saying is, it seems really stupid for people who can’t be decent parents to have kids.”

“Oh, now I get it. Now I’m stupid.”

“What?” I’d look across the table to my sister again, but she’d be pushing her chair back, on her way to the fridge to pour herself another glass of milk. “No, Dad. I didn’t—”

“You know, if only you were a boy, I’d be able to teach you something about having such a smart mouth.”

He’d go back to eating after that, and I’d stare down at my white thighs, then squeeze my fingernails into them till it killed. I’d wish that I was a boy, too, because at least then there would be a chance I might become more powerful than my father someday.

More unsettling than those debates were the other kind of fights we had—the ones that erupted out of what I could’ve sworn were perfectly innocent sentences. That summer, the thing that seemed to set my father off most was asking how his day had been. Though I’d ask as soon as he came in from work, he’d ignore the question until after he’d gotten his beer out of the fridge, taken a seat at the table, and started stabbing at the chicken breast on his plate. Once the anticipation had become unbearable, he’d finally answer. “What do you care how my day was?” he’d say. “That is one phony question if I ever heard one.”

“No, it’s not.” My eyes would widen. “I do care.”

“Do you have any idea how hot it was out there today?”

“Maybe ninety-nine degrees?”

“That’s right. And do you know what it feels like to be raking hot asphalt with the sun beating down on you when it’s ninety-nine degrees?”

All I knew was that it couldn’t feel too great, not when I’d been uncomfortable reading a book in the shade under the big tree in our front yard.

He went on. “But I go out there and bust my tail every day so I can provide for you guys. And you don’t care! What do you ever do for me?”

“We do stuff,” I’d say.

He’d laugh. “Oh yeah? Like what?”

I’d mention that I’d made dinner.

He’d laugh again. “And who paid for the food?”

He had, of course. His point seemed to be that nothing I did would have any meaning without him.

Things would degenerate from there, and as we kept quibbling, everything I thought I knew at the beginning of the conversation became uncertain. Did I really care about him? Did I really want to hear how his day had been? Maybe I didn’t—not if it meant him flipping out like this. So, I probably didn’t care about him. Let’s face it: I hated him. No wonder he didn’t love me.

“Oh, now here we go,” my father would say, waving a hand in my direction. “As if I don’t have enough problems. Now she’s crying.”

“I am not crying,” I’d say, even though I was. I’d clench my teeth and tense all my muscles, trying to control myself.

“I’d like to cry, too,” my father would say. “But what would happen if I cried? If I let myself fall apart, what would happen to you guys?”

I’d never have much interest in finishing my food after that.

That fall, after I became a freshman at an all-girls’ Catholic high school, I kept chiseling away at myself, trying to purify myself more, and to need less. The skinnier I got, though, the tougher it became to stick to my self-improvement plan. The problem wasn’t that starving had become physical torture, although it had. I was down to three hundred calories a day by then: a tiny serving of Special K with watered-down skim milk and a blue packet of Equal for breakfast; a green apple for lunch; a rice cake or two later in the afternoon; and some vegetables and canned tuna for dinner. Exercising had become painful, too. Somehow, I’d made it onto the varsity soccer team, and our workouts were far more intense than anything I’d been doing on my own—yet I refused to stop doing a nightly calisthenics routine in the secrecy of my room. I was chronically exhausted and chronically freezing, without any body fat to keep me warm. But despite how bad my body felt, my mind felt better than ever—even if it didn’t exactly feel good.

No, the real obstacle was that the adults around me had started to notice what I was doing. My new teachers wanted to know if I’d always been so thin. My father kept saying he didn’t think it was normal for a girl my age to be so skinny. I knew they’d all try to stop me if they found out the truth, so I did everything I could to hide myself. I didn’t want to go back to a life without dieting to give it shape and meaning. So I’d spend my lunch hour in the library with my books open in front of me, too hungry to concentrate, watching Sister Concepta in her white habit and black veil as she watered the plants. To make myself look heavier, I’d wear an undershirt and long underwear beneath my blue oxford blouse, and a pair of boxer shorts below my plaid wool skirt. As a bonus, all the extra padding helped me stay warm. Instead of changing into my soccer clothes in the locker room with everyone else, I’d do it in the handicapped bathroom downstairs, making sure to keep my underlayers on and to stuff my thick shin guards into my socks before anyone saw me. At home I wore huge clothes (ones that used to fit perfectly) to cover myself up, but they didn’t do much to calm my father’s suspicions. Eventu- ally he and I started to battle over a new topic: how much I’d eaten that day. I always lied, saying I’d stuffed my face before he came home, or that our coach had gotten us pizza after practice again (not that she ever had). I think my father wanted to believe me instead of finding out there was another worry to add to his list. And it was easy to evade him, since my soc- cer schedule had made it tough for me to remain family chef; we were fending for ourselves when it came to dinner by then.

Though he would still yell at me, my father also began to cajole. “Please eat,” he would say. “For me? A little food’s not going to hurt you.” As satisfying as it was to hear him plead, the better pleasure was knowing that my body was finally doing what I wanted it to do. It had been a long time since anything he said had been able to make me cry; I thought maybe he’d never be able to do it again. I was finally beating my father at our ongoing battle of wills—and I’d done it not by getting bigger, but by getting smaller.

By late October, things started happening that I couldn’t cover up with clothes or lies. My sister and I were walking to the bus one rainy morning when, seeing me struggle under the weight of my backpack, she tried to help me by pushing up the bottom, thinking she would hold it for a while. But I was so rickety that the shift threw me off balance and I fell backward, cracking my tailbone against the sidewalk. I would have lain there forever, staring up at the gray sky, but my sister could see the bus coming, so she pulled me up and tried to get me to run. The strange tingling pain I felt at the bottom of my spine, like the kind you feel after you whack your funny bone, made me limp for the rest of the day.

During soccer practice that afternoon, my coach, Miss Sawyer, called me off the field. “What the heck happened to you?” she said. Miss Sawyer was a boyish, fortysomething woman who wore khakis with V-neck sweaters and boat shoes; her blond hair was short and her legs were as bowed as a jockey’s. On the day she posted the list of people who’d made the cut for the team, I stopped by her office and asked why she’d chosen me. Because she’d never seen anyone with more heart, she said, which sounded strange: I didn’t feel like I had one left. I went straight into the bathroom after that and sobbed, because the only way I’d gotten through the excruciating tryouts was by telling myself it would all end soon; I was sure I’d never get picked.

Now she was waiting for me to answer her. I shrugged. “I fell this morning, and I’m a little sore. But I’ll be fine.”

“Why don’t you take a break till you feel better?”

“No, no,” I said, trying to sound calm. Ditching practice was not an option: If I didn’t burn those calories, I’d despise myself. Plus, I’d have to stay up late in my room, doing more sit-ups and push-ups and leg lifts to make up for it, and I was too tired for that. “I’ll be fine. Really. Just let me practice. I don’t want everyone to totally lose respect for me. I’m already the worst on the team. Please let me practice, Miss Sawyer, please?”

She gave in. “But I’m keeping an eye on you, skinny,” she said. “You haven’t been looking so good lately.”

A few days later, foot sores that had been coming on slowly made me more of a cripple than I’d been after the wipeout. My bony feet had been rubbing dangerously against my cleats for weeks by then, eroding the skin and forming holes—my stigmata—that slowly got deeper around both my ankles. For a while, the pain was barely noticeable if I covered the wounds with Band-Aids, then wrapped Ace bandages around them and wore an extra pair of socks. But one afternoon I hit my saturation point, and after tying my laces, I could barely hobble from the bathroom to the field.

Practice that day started with wind sprints, and I felt my spikes cutting into me with every step. Miss Sawyer called me over before I’d even finished the first leg. “You look terrible out there! Like a drunk with two broken feet.” She forced a laugh, but there was uneasiness in it. “What’s going on?”

I shook my head. “I guess it still hurts from when I fell before. I don’t know. Probably nothing. Once I warm up, I’ll be fine.”

I didn’t quite believe myself, and apparently neither did Miss Sawyer. She squinted at me. “You’re sitting out today.”

“But Miss Sawyer—”

“No buts! Except yours on that bench. Enough is enough. Get one of your books if you want to study. Otherwise, sit and watch.”

When I got home later that day, Miss Sawyer had left a message for my father on our answering machine.

“Could you please call me as soon as you can?” her recorded voice said.

I erased it, but my time was running out. The next morning, I was in Spanish class with Sister Carol—a tall, athletic nun with curly silver-brown hair; a tough teacher, but fair. I was sitting in the front row of desk chairs, near the windows and the sputtering white radiators, and had one of my legs wrapped tightly around the other for warmth. As we translated sentences from our book, my head kept nodding with exhaustion; every time it bounced to the end of my neck, I snapped it back and tried to shake myself awake. Finally, the bell rang and we all prepared to leave, rustling our graded quizzes and packing our bags. When I was ready, I tried to stand, but my left leg collapsed under me.

“Are you okay?” a chorus of girls murmured. “What happened?”

I had no idea. I was sprawled on the cold marble floor; that was all I knew. Had I slipped? I must have. Embarrassed, I tried to get up, but as soon as I put weight on my foot, it collapsed again and I was back to the floor.

“Oh my God,” someone behind me whispered. “What’s wrong with her?”

Sister Carol seemed to think I was trying to be a clown. She put her hands on her hips and said, “¿Cuál es el problema?”

I wanted to tell her I didn’t think this was any time for practicing mi español. “My leg,” I answered stubbornly, in English.

“Un dolor?” she said. (A pain?)

“No,” I said, my voice cracking. “More like . . . I can’t feel anything. Like it went to sleep, but it’s not waking up.” I was panicking then, realizing the truth of what I was saying.

Sister Carol asked the girl behind me to help her right me, and once they had me in a standing position, Sister Carol asked if I thought I could walk on my own. I shook my head.

“Try,” she said. “We’ll help you.”

Using the two of them as crutches, I teetered up the aisle, toward the door, floundering, taking panicked shallow breaths before I figured out that even though my left leg didn’t seem to be working from the knee down, I could more or less get it to function by dragging it forward and pivoting off it.

Some seniors who’d filed in for the next class were staring at me.

“I think I’m okay now,” I whispered to Sister Carol. We were near the chalkboard.

Sister Carol’s lips were pursed. “Try going to the podium and back on your own.”

Using my new method, I was able to shuffle up and down that catwalk, but I knew it didn’t look pretty.

Once I returned to Sister Carol, she wiped the tears off my cheek with a hard thumb and, motioning at the other girl, said, “She’s going to take you up to the nurse’s office. I’d do it myself, but I need to teach this class.”

Our school was small, and I remember everything, so it’s funny that I can’t remember that girl’s name or even her face. All I can remember was that I didn’t think she was that cool, and yet, once we got out in the hall, she walked a few steps ahead of me. I knew why: She was embarrassed to be seen with me. She didn’t want anyone to think she was friends with the sniffling, broken-down weirdo. I understood how she felt.

Maura Kelly

For a few weeks during the summer before high school, I resembled one of the catwalkers from the pages of The New York Times’ s style supplement, which covered my bedroom wall in a Scotch Tape collage. It wasn’t my face that was like theirs, or my clothes. (My usual look was a pocket T-shirt and cutoff jeans shorts, while the glossy girls wore kimono dresses, peacock-feather hats, and short pointy boots like white cockatoos.) It was my body. My stomach had caved in. My hip bones flared like wings. My legs met only at the knees and ankles: There was a teardrop-shaped gap between my thighs, and another between my calves. Knobby bones protruded dangerously from my wrists and elbows. My arms seemed longer, and from the ends of them, my enormous hands flopped, awkward as a marionette’s. I was barely thirteen, five feet and five inches tall, and down to 90 pounds from 110.

My transformation thrilled me.

Still, I wasn’t quite thin enough. So I kept going, and the changes became even more exciting. The colored hairbands I kept around my wrist got so loose that I could easily slide them up to my elbow. If I pressed my hand around the part of my arm where the shoulder met the biceps, I could touch my thumb with the pad of my ring finger. I could also put both hands around my thigh and touch thumb to thumb, pinky to pinky. I’d measure myself like that again and again when no one was watching, usually in the bathroom stall at school; it reassured me that I hadn’t somehow gotten fatter in the hours since I’d been on the scale that morning. My ribs became so visible that I could count them not only from the front but also, if I used two mirrors, from the back as they curved out from the knotted rope of my spine.

I began to resemble someone else tacked up in my room: Jesus Christ.

Now there was an icon. There was a guy who knew something about style: the original long-haired, emaciated, rock- star type. But it wasn’t just Jesus’ body that I admired; it was his suffering, too, and the way it made people love him. Jesus had been my first role model, and I still respected the guy, even if I was a full-fledged nonbeliever by then. As he hung from the crucifix my dead mother had positioned over my dresser, Jesus inspired me—with his skeleton hanging out of his skin, his blood dripping from his crown of thorns, and his face turned imploringly upward in the moment before his death as he said, “My God, my Father, why have you forsaken me?”

I knew how Jesus felt, asking that question. When my mother died of cancer the summer I turned eight, I felt pretty forsaken myself. I had no idea she was dying. I knew she was sick, of course, but my parents told my sister and me that she just had a very bad cold, kind of like chicken pox, except the bumps were inside.

Her illness replaced me—the baby—and became the most important thing in my mother’s life. Before she’d gotten sick, she loved everything I did, whether it was the Little Tea- pot dance, or one of my typically opinionated comments (“I don’t want to grow up to be like you, Mommy, always driv- ing my kids around”), or just burying my face in her neck to cry. But after she was diagnosed, I wasn’t as easy to love; at least, it was harder to get her full attention. For the last four years of her life, she spent one week out of every month in the hospital getting chemotherapy—a word I could say but not define—and when she was home, she spent a lot of time in bed with the curtains drawn. She didn’t like it when I was loud, and sometimes she was too weak to even kiss me back after I pressed my lips against her cheek. Her head would just stay on the pillow.

Whenever she wasn’t feeling well, I tried to leave her alone. I tried not to need anything from her. I became self-conscious: worried about what effect my actions would have, and aware of my own presence in a room.

Everyone—my parents, my other relatives, and the priests and nuns we knew, including my uncle Father Jimmy—told me that my mother might get better if I was a very good girl and asked God to help us. I would have done anything to get my mother back the way she used to be, so I prayed. I also sang at church with my family on Sunday mornings, as loudly and clearly as I could, because the pastor said singing was praising God twice. (I just hoped that Juan-Juan Santiago, who sat across the aisle from us with his parents and little brother, wouldn’t notice what a geek I was.) One of my favorite hymns was in praise of lasagna—or so I thought, till my mother caught on to what I was saying, and explained that the word was actually hosana, which means, roughly, “God is great.” And to show the devil I hated him, I’d jump up and down in the grass—as close to Hell as I could get—until I’d exhausted myself. Then I’d lie on the ground, blowing kisses up to the angels. Everyone said God was always watching over me, which was nice, especially since my mother wasn’t anymore. My growing love for God, and His for me, was helping to fill the hole my mother was making. I’d picture Him with the big white beard, in a white robe, in a white throne that floated on the clouds, smiling down at me, and I’d smile back.

It wasn’t just through physical actions that I tried to make myself God’s favorite; there were also the things I’d do in my head. During Mass, I’d recite the Penitential Rite with the rest of the congregation: “I have sinned through my own fault, in my thoughts and in my words, in what I have done, and in what I have failed to do.” I’d feel gravely sorry about all my transgressions: how I’d once again stuffed myself with chocolate-chip cookies and marshmallows in the morning, before my parents woke up; how I’d punched my sister in the rear end; how I’d stuck my tongue out at my father when he wasn’t watching. I’d pinch myself once on the thigh for each sin, and resolve to become a better person. I knew how important it was to God that my head be as pure as my actions, so whenever I had bad thoughts—like how much I hated the new Indian kid in our class, Raj, because he smelled funny and was hairy—I’d start to pray, trying to push the evil away. I was trying so hard and God loomed so large in my mind (even larger than Juan-Juan) that I was confident I was one of His favorites.

But I started to wonder if that was true after my mother died that August, twenty days after my birthday. I was so unprepared that when my father first told me I laughed. “Really, when can we pick her up from the hospital?” I said. “Tell me.” He only stared at me. “Tell me,” I insisted. Still, he didn’t speak, and my sister, sitting in his lap, started to cry. That unsettled me enough that I went to get a closer look at my father. When tears started coming down his face, too, I was terrified. Something had to be seriously wrong, but I was too young—or too shocked—to really understand what was going on.

I didn’t give up the hope that my mother might somehow pop out of her coffin until I first saw her in the wooden box at the wake. That’s when I started to appreciate what being dead meant. The rosy blush my mother usually wore had been replaced by two heavy circles of red on her cheeks; instead of her favorite mauve lipstick, there was a brown smear on her mouth. I could see the pores on her face as clearly as if they’d been made with a pencil. Her skin was thick and hard and unyielding under my fingertips, like football leather. I realized there was no way that body was going to sit up and say “Surprise!” and then reach out to tickle me under the arms. I climbed up on the kneeler and kissed her, maybe because I still had fairy-tale hopes about what that could do for a dead person. But it didn’t make any difference. Those rubber lips took away any doubt I had left—about her death, anyway.

But suddenly, everything else in my life was thrown into question. It wasn’t only my mother who was gone: It was my understanding of the universe, of myself, of God, and even of my own father. Overwhelmed by his grief, bills, and the responsibility of trying to raise two girls alone, he became a stranger to me: moody, unpredictable, and frightening—the big villain in my life. Suddenly, we were shouting at each other so much that I believed it when the first nanny we had after my mother died, a young woman from northern Ireland named Marie, told me again and again my father didn’t love me. Every night, I waited for him to come home with the worst longing and the most terrible fear, wondering if he would prove Marie right one more time.

I couldn’t count on my so-called Heavenly Father anymore, either, considering I was convinced that He’d killed my mother to punish me. (He couldn’t have had it out for anyone else in my family, I figured, since my connection to Him was more intense than theirs, for better and for worse.) What I couldn’t figure out was why God was so angry with me. In what way had I offended Him? I kept going over and over everything that I’d done and thought in the weeks leading up to my mother’s death, the way a guilty lover will after a suicide, and though there were all the usual little bad things—sneaking cookies, punching my sister, hating Raj—there wasn’t anything new and outstandingly wicked that would explain God’s act of vengeance against me. Also, I was nowhere near as bad as some of the other kids in my town, especially not the ones from the public middle school, who smoked cigarettes on the railroad tracks behind my house, or had sex in the old band shell at Memorial Park, or did drugs in their cars in the Burger King parking lot.

Since it seemed obvious I couldn’t have done anything to bring on the wrath of God, I figured there must be something inherently wrong with me. Did He hate me because I wasn’t as good in my heart as I’d thought? Probably. And maybe my mother hadn’t really loved me, either. Why else would she have left without even saying good-bye, or that she’d miss me?

Those kinds of questions were hard to face, so eventually I convinced myself, as best as I could, that the problem wasn’t with me but with Catholicism. I’d tried so hard to follow the rules, in my actions and my thoughts, and what had it got- ten me but a dead mother? I didn’t want to live that way anymore. But I did want something to believe in—a system that was more transparent and would yield visible results. I wanted proof that I was good.

Dieting eventually became a replacement religion for me, with its own set of commandments and rituals. It became a way for me to be my own god and my own creation—Pygmalion and Galatea in the same human body. It became a perverse method for mothering myself: I structured my meals, my days, and my thoughts around it. Dieting became my internal compass. It became the new thing for me to be the best at. I was so devoted that I was practically ready to give up my life for it.

But when I first started losing weight, toward the end of eighth grade, I had no idea I would become a fanatic. It was far more simple than that. All I wanted was to look like I had at the beginning of the school year, before my abdomen began to protrude under the band of my Hanes underwear. Though I realize now it was just an early sign of puberty, that curve disgusted me. I felt like a dog in heat, with it poking out of me. I had to be out of control if I’d let my body turn into that. And I figured if I lost five pounds—just five—my stomach would be flat again. But as it turned out, I had to drop closer to fifteen pounds before the curve disappeared, and once I got that far, I couldn’t stop. I was addicted to losing.

Part of the appeal was how much dieting simplified my life. Nothing else mattered but the numbers: how many calories I’d eaten that day; how many pounds I’d lost in the last week, or month; how many leg lifts or push-ups I’d do that night. I’d add, subtract, and double-check constantly. I felt like I was moving toward some great new salvation. Instead of praying when I felt scared or guilty or lonely, I’d turn to the numbers, like my grandmother to her wooden rosary beads, and they’d calm me down.

My head became so full of equations and plans about what I would eat and what exercises I would do that I didn’t have room for much else. I stopped worrying about not having any boobs even though every other girl in my class had them. I stopped caring about how all the boys, including Juan-Juan, had a crush on my best friend, Catherine McMurtry. I stopped feeling guilty about all the games of Truth or Dare and Seven Minutes in Heaven I’d played, and how it made me feel weird and gross but also excited whenever there was a boy’s tongue in my mouth. I stopped thinking about all those times Marie had told me that my father didn’t love me. My calculations not only filled up all the empty spaces in my head; they also helped me determine the value of my self. On any day that I’d eaten less, worked out longer, or lost more, it didn’t mean I was good, but at least I wasn’t bad.

The most important number, though, was one I had no idea how to determine: the weight I’d have to be to let myself stop, the weight that would mean I was finally good enough. In the very beginning, I thought it would be 105. Then it became one hundred. Ninety-five. Ninety. By the time I weighed eighty-five, I started to wonder if I’d ever be able to predict what the right weight was. Maybe I wouldn’t know until I reached it.

That summer before high school, when the dieting fever really started to take hold, I was fighting more than ever with my father, an Irish immigrant who made his living paving people’s driveways and laying concrete. Maybe part of the problem was that there was no other adult in the house to help keep us in our corners: My father hadn’t (and still hasn’t) remarried, and we were between housekeepers at that point. He hired and fired sixteen different women before I got to college, but never before I got attached to them; each one of them seemed like some kind of mother to me.

Our door started to revolve after he kicked out Marie, who’d been with us for four years. She’d become slowly obsessed with my father, and eventually demanded that he marry her, though they’d never been romantically involved. She pleaded with him, saying that she was already acting like a mother to my sister and me; why not make her role official?

My father turned her down. One night shortly after the rejection, Marie pulled a huge knife out of the kitchen drawer and threatened to kill herself with it. I grabbed the cleaver away from her; my father ordered her out of the house, and we never saw her again, though for years she prank-called our house and one time even phoned Catherine McMurtry’s house, looking for me.

It wasn’t a coincidence that my obsession with dieting started soon after my father fired Marie. Screwed up as she was, she’d been a temporary stay against the confusion that ensued after my mother was gone. In the four years that she’d been with us, I’d come to depend on her, especially because I didn’t feel like I could depend on my father anymore. It never occurred to me to ask him if Marie was right all those times she said he didn’t love me; it seemed obvious he didn’t. After all, I apparently had a special talent for saying things that would infuriate him so much that he’d give me the silent treatment for days, even weeks. During those periods, he’d do everything he could to avoid looking at me, even keeping his head down if we were in the kitchen together.

Often our arguments would start over things in the news. My father was a conservative then, despite the fact that he also subscribed to The New York Times, whereas I was a born liberal, despite the fact that I’d represented Ronald Reagan in some faux presidential debate we’d had at school. I would read the Week in Review section every Sunday so I’d have ammunition when my father started in about something.

That summer, abortion made the headlines. (justices uphold rights by narrow vote, The New York Times said, after the Supreme Court ruled against a Pennsylvania anti-abortion law.) The topic was big in our kitchen, too. We’d get into it after my father arrived home, as the three of us were sitting down to a dinner I’d made. I always volunteered to cook whenever no one was on the payroll. My sister wasn’t any good at it—she’d once tried to boil spaghetti without put- ting any water in the pot. Besides, I thought my father would like me better if I took on some adult responsibilities. Because the weather was warm and we didn’t have air-conditioning, my father would preside at the head of the table wearing only his tar-blackened jeans and his mustard yellow work boots, in all his muscled bulk, smelling of sour sweat. His huge biceps always looked flexed even when they weren’t, and though his pecs had gotten slightly flaccid with middle age, they were still powerful. His torso and arms were evenly burned the same leathery brown color—no “farmer’s tan” for him—because he liked to take his shirt off in the sun when he was working.

Who knows exactly how our “discussions” would start, but soon enough, I’d swallow the instant rice I had in my mouth so I could say, “I just think a woman should be able to do whatever she wants with her body, is all. It seems pretty obvious to me.”

My father would raise his caterpillar eyebrows at me, and his face would twist from disbelief to disparagement to rage, and I knew things were about to get absurd.

“ ‘Whatever she wants with her body’—oh yeah?” He’d pound his Heineken bottle on the table. “So if you wanted to jump off a bridge, I should let you do that?”

“Wait—what?” Realizing my paper napkin had fallen to the floor, I’d grab another out of the wooden holder in the middle of the table so I could have something to hold on to. “I didn’t say anything about jumping off a bridge. Besides, suicide is totally different from abortion. There’s no law against it, I don’t think. I mean, no one really cares what you do to yourself—”

“So what are you saying? I should let you kill yourself?”

I felt outrage like a stab in my chest. “What?” I’d glance over at my sister, hoping she would at least roll her eyes at me—that she would give me some sign I wasn’t losing my mind—but she would refuse to look up from the wilted heap of green beans on her plate.

“You heard me,” he said.

“Of course you shouldn’t let me kill myself.”

My father would point his knife at me. “But it’s okay to kill babies?”

“This is crazy. First of all, we don’t even know when they become alive!” I’d slam my own fist on the table, and the milk in my glass would jump.

My father would drop his utensils onto his plate with a clatter and glare at me. “You just watch your step now. Just watch your step.”

I’d try to calm down. “All right, look. All I’m saying is a woman shouldn’t be forced to ruin her life just because—”

“Ruin her life? Well, isn’t that something. Isn’t that something. What if your mother thought you were going to ruin her life—did that ever occur to you?”

“That’s totally different. Isn’t it? It’s not like you guys were so poor you didn’t want to have me. Right? Right?”

He wouldn’t answer me directly. “Did you know that when your sister was born, they weren’t going to let me take her or your mother out of the hospital? I had no insurance. I didn’t have the money to pay the bill. I told them, ‘You goddamn better let me take them out—that’s my wife and my baby daughter we’re talking about.’ Did you know that?”

I did know. He’d told me a thousand times. But I wished he’d get back to my question.

Instead, he’d go on. “Where would you be now if your mother had gotten an abortion? You ever think of that?”

“That’s beside the point. All I’m saying is, it seems really stupid for people who can’t be decent parents to have kids.”

“Oh, now I get it. Now I’m stupid.”

“What?” I’d look across the table to my sister again, but she’d be pushing her chair back, on her way to the fridge to pour herself another glass of milk. “No, Dad. I didn’t—”

“You know, if only you were a boy, I’d be able to teach you something about having such a smart mouth.”

He’d go back to eating after that, and I’d stare down at my white thighs, then squeeze my fingernails into them till it killed. I’d wish that I was a boy, too, because at least then there would be a chance I might become more powerful than my father someday.

More unsettling than those debates were the other kind of fights we had—the ones that erupted out of what I could’ve sworn were perfectly innocent sentences. That summer, the thing that seemed to set my father off most was asking how his day had been. Though I’d ask as soon as he came in from work, he’d ignore the question until after he’d gotten his beer out of the fridge, taken a seat at the table, and started stabbing at the chicken breast on his plate. Once the anticipation had become unbearable, he’d finally answer. “What do you care how my day was?” he’d say. “That is one phony question if I ever heard one.”

“No, it’s not.” My eyes would widen. “I do care.”

“Do you have any idea how hot it was out there today?”

“Maybe ninety-nine degrees?”

“That’s right. And do you know what it feels like to be raking hot asphalt with the sun beating down on you when it’s ninety-nine degrees?”

All I knew was that it couldn’t feel too great, not when I’d been uncomfortable reading a book in the shade under the big tree in our front yard.

He went on. “But I go out there and bust my tail every day so I can provide for you guys. And you don’t care! What do you ever do for me?”

“We do stuff,” I’d say.

He’d laugh. “Oh yeah? Like what?”

I’d mention that I’d made dinner.

He’d laugh again. “And who paid for the food?”

He had, of course. His point seemed to be that nothing I did would have any meaning without him.

Things would degenerate from there, and as we kept quibbling, everything I thought I knew at the beginning of the conversation became uncertain. Did I really care about him? Did I really want to hear how his day had been? Maybe I didn’t—not if it meant him flipping out like this. So, I probably didn’t care about him. Let’s face it: I hated him. No wonder he didn’t love me.

“Oh, now here we go,” my father would say, waving a hand in my direction. “As if I don’t have enough problems. Now she’s crying.”

“I am not crying,” I’d say, even though I was. I’d clench my teeth and tense all my muscles, trying to control myself.

“I’d like to cry, too,” my father would say. “But what would happen if I cried? If I let myself fall apart, what would happen to you guys?”

I’d never have much interest in finishing my food after that.

That fall, after I became a freshman at an all-girls’ Catholic high school, I kept chiseling away at myself, trying to purify myself more, and to need less. The skinnier I got, though, the tougher it became to stick to my self-improvement plan. The problem wasn’t that starving had become physical torture, although it had. I was down to three hundred calories a day by then: a tiny serving of Special K with watered-down skim milk and a blue packet of Equal for breakfast; a green apple for lunch; a rice cake or two later in the afternoon; and some vegetables and canned tuna for dinner. Exercising had become painful, too. Somehow, I’d made it onto the varsity soccer team, and our workouts were far more intense than anything I’d been doing on my own—yet I refused to stop doing a nightly calisthenics routine in the secrecy of my room. I was chronically exhausted and chronically freezing, without any body fat to keep me warm. But despite how bad my body felt, my mind felt better than ever—even if it didn’t exactly feel good.

No, the real obstacle was that the adults around me had started to notice what I was doing. My new teachers wanted to know if I’d always been so thin. My father kept saying he didn’t think it was normal for a girl my age to be so skinny. I knew they’d all try to stop me if they found out the truth, so I did everything I could to hide myself. I didn’t want to go back to a life without dieting to give it shape and meaning. So I’d spend my lunch hour in the library with my books open in front of me, too hungry to concentrate, watching Sister Concepta in her white habit and black veil as she watered the plants. To make myself look heavier, I’d wear an undershirt and long underwear beneath my blue oxford blouse, and a pair of boxer shorts below my plaid wool skirt. As a bonus, all the extra padding helped me stay warm. Instead of changing into my soccer clothes in the locker room with everyone else, I’d do it in the handicapped bathroom downstairs, making sure to keep my underlayers on and to stuff my thick shin guards into my socks before anyone saw me. At home I wore huge clothes (ones that used to fit perfectly) to cover myself up, but they didn’t do much to calm my father’s suspicions. Eventu- ally he and I started to battle over a new topic: how much I’d eaten that day. I always lied, saying I’d stuffed my face before he came home, or that our coach had gotten us pizza after practice again (not that she ever had). I think my father wanted to believe me instead of finding out there was another worry to add to his list. And it was easy to evade him, since my soc- cer schedule had made it tough for me to remain family chef; we were fending for ourselves when it came to dinner by then.

Though he would still yell at me, my father also began to cajole. “Please eat,” he would say. “For me? A little food’s not going to hurt you.” As satisfying as it was to hear him plead, the better pleasure was knowing that my body was finally doing what I wanted it to do. It had been a long time since anything he said had been able to make me cry; I thought maybe he’d never be able to do it again. I was finally beating my father at our ongoing battle of wills—and I’d done it not by getting bigger, but by getting smaller.

By late October, things started happening that I couldn’t cover up with clothes or lies. My sister and I were walking to the bus one rainy morning when, seeing me struggle under the weight of my backpack, she tried to help me by pushing up the bottom, thinking she would hold it for a while. But I was so rickety that the shift threw me off balance and I fell backward, cracking my tailbone against the sidewalk. I would have lain there forever, staring up at the gray sky, but my sister could see the bus coming, so she pulled me up and tried to get me to run. The strange tingling pain I felt at the bottom of my spine, like the kind you feel after you whack your funny bone, made me limp for the rest of the day.

During soccer practice that afternoon, my coach, Miss Sawyer, called me off the field. “What the heck happened to you?” she said. Miss Sawyer was a boyish, fortysomething woman who wore khakis with V-neck sweaters and boat shoes; her blond hair was short and her legs were as bowed as a jockey’s. On the day she posted the list of people who’d made the cut for the team, I stopped by her office and asked why she’d chosen me. Because she’d never seen anyone with more heart, she said, which sounded strange: I didn’t feel like I had one left. I went straight into the bathroom after that and sobbed, because the only way I’d gotten through the excruciating tryouts was by telling myself it would all end soon; I was sure I’d never get picked.

Now she was waiting for me to answer her. I shrugged. “I fell this morning, and I’m a little sore. But I’ll be fine.”

“Why don’t you take a break till you feel better?”

“No, no,” I said, trying to sound calm. Ditching practice was not an option: If I didn’t burn those calories, I’d despise myself. Plus, I’d have to stay up late in my room, doing more sit-ups and push-ups and leg lifts to make up for it, and I was too tired for that. “I’ll be fine. Really. Just let me practice. I don’t want everyone to totally lose respect for me. I’m already the worst on the team. Please let me practice, Miss Sawyer, please?”

She gave in. “But I’m keeping an eye on you, skinny,” she said. “You haven’t been looking so good lately.”

A few days later, foot sores that had been coming on slowly made me more of a cripple than I’d been after the wipeout. My bony feet had been rubbing dangerously against my cleats for weeks by then, eroding the skin and forming holes—my stigmata—that slowly got deeper around both my ankles. For a while, the pain was barely noticeable if I covered the wounds with Band-Aids, then wrapped Ace bandages around them and wore an extra pair of socks. But one afternoon I hit my saturation point, and after tying my laces, I could barely hobble from the bathroom to the field.

Practice that day started with wind sprints, and I felt my spikes cutting into me with every step. Miss Sawyer called me over before I’d even finished the first leg. “You look terrible out there! Like a drunk with two broken feet.” She forced a laugh, but there was uneasiness in it. “What’s going on?”

I shook my head. “I guess it still hurts from when I fell before. I don’t know. Probably nothing. Once I warm up, I’ll be fine.”

I didn’t quite believe myself, and apparently neither did Miss Sawyer. She squinted at me. “You’re sitting out today.”

“But Miss Sawyer—”

“No buts! Except yours on that bench. Enough is enough. Get one of your books if you want to study. Otherwise, sit and watch.”

When I got home later that day, Miss Sawyer had left a message for my father on our answering machine.

“Could you please call me as soon as you can?” her recorded voice said.

I erased it, but my time was running out. The next morning, I was in Spanish class with Sister Carol—a tall, athletic nun with curly silver-brown hair; a tough teacher, but fair. I was sitting in the front row of desk chairs, near the windows and the sputtering white radiators, and had one of my legs wrapped tightly around the other for warmth. As we translated sentences from our book, my head kept nodding with exhaustion; every time it bounced to the end of my neck, I snapped it back and tried to shake myself awake. Finally, the bell rang and we all prepared to leave, rustling our graded quizzes and packing our bags. When I was ready, I tried to stand, but my left leg collapsed under me.

“Are you okay?” a chorus of girls murmured. “What happened?”

I had no idea. I was sprawled on the cold marble floor; that was all I knew. Had I slipped? I must have. Embarrassed, I tried to get up, but as soon as I put weight on my foot, it collapsed again and I was back to the floor.

“Oh my God,” someone behind me whispered. “What’s wrong with her?”

Sister Carol seemed to think I was trying to be a clown. She put her hands on her hips and said, “¿Cuál es el problema?”

I wanted to tell her I didn’t think this was any time for practicing mi español. “My leg,” I answered stubbornly, in English.

“Un dolor?” she said. (A pain?)

“No,” I said, my voice cracking. “More like . . . I can’t feel anything. Like it went to sleep, but it’s not waking up.” I was panicking then, realizing the truth of what I was saying.

Sister Carol asked the girl behind me to help her right me, and once they had me in a standing position, Sister Carol asked if I thought I could walk on my own. I shook my head.

“Try,” she said. “We’ll help you.”

Using the two of them as crutches, I teetered up the aisle, toward the door, floundering, taking panicked shallow breaths before I figured out that even though my left leg didn’t seem to be working from the knee down, I could more or less get it to function by dragging it forward and pivoting off it.

Some seniors who’d filed in for the next class were staring at me.

“I think I’m okay now,” I whispered to Sister Carol. We were near the chalkboard.

Sister Carol’s lips were pursed. “Try going to the podium and back on your own.”

Using my new method, I was able to shuffle up and down that catwalk, but I knew it didn’t look pretty.

Once I returned to Sister Carol, she wiped the tears off my cheek with a hard thumb and, motioning at the other girl, said, “She’s going to take you up to the nurse’s office. I’d do it myself, but I need to teach this class.”

Our school was small, and I remember everything, so it’s funny that I can’t remember that girl’s name or even her face. All I can remember was that I didn’t think she was that cool, and yet, once we got out in the hall, she walked a few steps ahead of me. I knew why: She was embarrassed to be seen with me. She didn’t want anyone to think she was friends with the sniffling, broken-down weirdo. I understood how she felt.

Recenzii

Praise for Going Hungry

“In revealing essays by men and women–young and old, thin and not thin, black, brown and white–this anthology lends remarkable texture to a subject that has been too often sensationalized and oversimplified.” –The New York Times

“Taylor writes with grace and insight of her self-imposed malnourishment.” –The New York Times Book Review

“Powerful. . . . Allows[s] the breadth and depth of anorexia to be revealed in the thorough, eloquent words of its sufferers. . . . [The essays are] beautiful pieces in and of themselves that help shed light on a powerful affliction.” –San Francisco Chronicle

“[Going Hungry’s] authors defy many of the stereotypes about eating disorders, and who suffers from them.” –Newsweek

“Eighteen women writers–and one man–share memories of anorexia’s tenacious grip in this eye-opening collection.” –People

“Those struggling with an eating disorder are sure to find among these personal essays at least one that will help them better understand their own condition, and provide company and hope.” –Publishers Weekly

“Going Hungry is a remarkable book. To read these powerful and articulate life stories of anorexia is to gain a kind of new understanding into the conflict, disconnection and seductiveness of this potentially lethal disease. The psychology of anorexia is difficult to comprehend but I felt at the end of reading this book that I had a much better, much more human grasp of what is like to live and struggle with the illness. The stories are deeply illuminating, in the fullest sense of the word.” –Kay Redfield Jamison, author of An Unquiet Mind

“In Going Hungry, writers of different ethnicities offer thoughtful personal perspectives on eating disorders. Of particular interest is the theme that anorexia nervosa can be an expression (albeit a harmful one) of a positive drive to accomplish something noteworthy and that such aspirations can be redirected into meaningful, productive endeavors. These messages inspire hope and provide a powerful counterforce to stereotypes that associate eating disorders with superficiality and vanity.” –Dr. David Herzog, Director of the Harris Center for Eating Disorders, Massachusetts General Hospital

“In revealing essays by men and women–young and old, thin and not thin, black, brown and white–this anthology lends remarkable texture to a subject that has been too often sensationalized and oversimplified.” –The New York Times

“Taylor writes with grace and insight of her self-imposed malnourishment.” –The New York Times Book Review

“Powerful. . . . Allows[s] the breadth and depth of anorexia to be revealed in the thorough, eloquent words of its sufferers. . . . [The essays are] beautiful pieces in and of themselves that help shed light on a powerful affliction.” –San Francisco Chronicle

“[Going Hungry’s] authors defy many of the stereotypes about eating disorders, and who suffers from them.” –Newsweek

“Eighteen women writers–and one man–share memories of anorexia’s tenacious grip in this eye-opening collection.” –People

“Those struggling with an eating disorder are sure to find among these personal essays at least one that will help them better understand their own condition, and provide company and hope.” –Publishers Weekly

“Going Hungry is a remarkable book. To read these powerful and articulate life stories of anorexia is to gain a kind of new understanding into the conflict, disconnection and seductiveness of this potentially lethal disease. The psychology of anorexia is difficult to comprehend but I felt at the end of reading this book that I had a much better, much more human grasp of what is like to live and struggle with the illness. The stories are deeply illuminating, in the fullest sense of the word.” –Kay Redfield Jamison, author of An Unquiet Mind

“In Going Hungry, writers of different ethnicities offer thoughtful personal perspectives on eating disorders. Of particular interest is the theme that anorexia nervosa can be an expression (albeit a harmful one) of a positive drive to accomplish something noteworthy and that such aspirations can be redirected into meaningful, productive endeavors. These messages inspire hope and provide a powerful counterforce to stereotypes that associate eating disorders with superficiality and vanity.” –Dr. David Herzog, Director of the Harris Center for Eating Disorders, Massachusetts General Hospital

Cuprins

Introduction Kate Taylor

Hunger Striking Maura Kelly

To Poison An Ideal Ilana Kurshan

Daughters of the Diet Revolution Jennifer Egan

On Thin Ice Francine du Plessix Gray

Hungry Men John Nolan

Black-and-White Thinking Latria Graham

Education of the Poet Louise Glück

Big Little Priscilla Becker

The Ghost of Gordolfo Gelatino Rudy Ruiz

Earthly Imperfections Lisa Halliday

Little Fish in a Big Sea Sarah Haight

How the Faeries Caught Me Francesca Lia Block

The Voice Trisha Gura

Finding Home Maya Browne

Shape-shifting Amanda Fortini

Earning Life Clara Elliot

Modeling School Elizabeth Kadetsky

Thirty Years Later, Still Watching the Scale Joyce Maynard

Acknowledgments

Hunger Striking Maura Kelly

To Poison An Ideal Ilana Kurshan

Daughters of the Diet Revolution Jennifer Egan

On Thin Ice Francine du Plessix Gray

Hungry Men John Nolan

Black-and-White Thinking Latria Graham

Education of the Poet Louise Glück

Big Little Priscilla Becker

The Ghost of Gordolfo Gelatino Rudy Ruiz

Earthly Imperfections Lisa Halliday

Little Fish in a Big Sea Sarah Haight

How the Faeries Caught Me Francesca Lia Block

The Voice Trisha Gura

Finding Home Maya Browne

Shape-shifting Amanda Fortini

Earning Life Clara Elliot

Modeling School Elizabeth Kadetsky

Thirty Years Later, Still Watching the Scale Joyce Maynard

Acknowledgments

Descriere

Twenty writers describe their experiences with anorexia from the distance of recovery, in this collection that is an important resource for parents, teachers, teenagers, and those who want to understand what goes through the mind of someone struggling with an eating disorder.