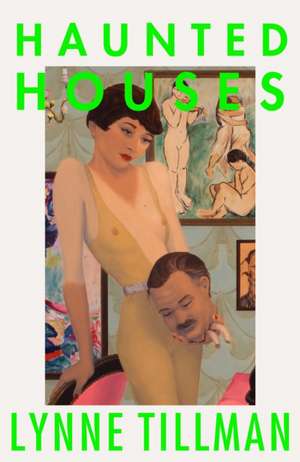

Haunted Houses

Autor Lynne Tillmanen Limba Engleză Paperback – 12 oct 2022

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (3) | 69.70 lei 3-5 săpt. | +9.39 lei 7-13 zile |

| Peninsula Press – 12 oct 2022 | 69.70 lei 3-5 săpt. | +9.39 lei 7-13 zile |

| Cursor – 28 iun 2011 | 89.06 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| Cursor – 11 oct 2016 | 100.59 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 69.70 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 105

Preț estimativ în valută:

13.34€ • 13.95$ • 11.08£

13.34€ • 13.95$ • 11.08£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 12-26 martie

Livrare express 26 februarie-04 martie pentru 19.38 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781913512170

ISBN-10: 1913512177

Pagini: 112

Dimensiuni: 129 x 198 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Peninsula Press

Colecția Peninsula Press

Locul publicării:United Kingdom

ISBN-10: 1913512177

Pagini: 112

Dimensiuni: 129 x 198 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Peninsula Press

Colecția Peninsula Press

Locul publicării:United Kingdom

Recenzii

Praise for Haunted Houses

"In Haunted Houses, Lynne Tillman chronicles the loneliness of childhood and incipient womanhood, the salvation of friendship, and the neurotic chain that binds perpetually needy daughters to their perpetually self-absorbed parents. . . . Her style is spare and compelling, the effect of clinical authenticity." — New York Times Book Review

"Ms. Tillman's characters are rigorously drawn , with a scrupulous regard for the truth of their inner lives . . . this is one of the most interesting works of fiction in recent times . . . Fans of both truth and fancy should find nourishment here." — LA Weekly

“Lynne Tillman's protagonists are so lifelike, engaging and accessible, one could overlook, though hardly remain unaffected by, the quality of her prose, with its unique balancing of character interrogation and headlong entertainment. Haunted Houses achieves that hardest of things: a fresh involvement of overheard life with the charisma of intelligent fiction. Its pleasures pull their weight.” -Dennis Cooper

“This complex and skillfully constructed novel has three separate storylines following the lives of three girls growing up in New York, maturing in a world of baffling freedoms and uncertainties.... Childhood fears, passionate friendships, sexual explorations, and the uncomfortable interdependency of parents and children are depicted with intelligence, honesty, and dark humor. But if you are looking for comfort and consolation, you must look elsewhere: Tillman writes about life as it is, not as we might wish it to be." — Sunday Times

Lynne Tillman's writing uncovers hidden truths, reveals the unnamable, and leads us into her personal world of pain, pleasure, laughter, fear and confusion, with a clarity of style that is both remarkable and exhilarating. Honest. Simple. Deep. Authentic. Daring... To read her is, in a sense, to become alive, because she lives so thoroughly in her work. Lynne Tillman is, quite simply, one of the best writers alive today." — John Zorn

"Lynne Tillman's haunted houses are Freudian ones — the psyches of three girls, Emily, Jane, and Grace, each wrestling with the psychological 'ghosts' that shape them . . . . Frequently shifting points of view are expressed in crisp sentences. Rather than forming a modernist stream of consciousness, however, the writing remains controlled." — Lucy Atkins, Times Literary Supplement

"In Haunted Houses, Lynne Tillman chronicles the loneliness of childhood and incipient womanhood, the salvation of friendship, and the neurotic chain that binds perpetually needy daughters to their perpetually self-absorbed parents. . . . Her style is spare and compelling, the effect of clinical authenticity." — New York Times Book Review

"Ms. Tillman's characters are rigorously drawn , with a scrupulous regard for the truth of their inner lives . . . this is one of the most interesting works of fiction in recent times . . . Fans of both truth and fancy should find nourishment here." — LA Weekly

“Lynne Tillman's protagonists are so lifelike, engaging and accessible, one could overlook, though hardly remain unaffected by, the quality of her prose, with its unique balancing of character interrogation and headlong entertainment. Haunted Houses achieves that hardest of things: a fresh involvement of overheard life with the charisma of intelligent fiction. Its pleasures pull their weight.” -Dennis Cooper

“This complex and skillfully constructed novel has three separate storylines following the lives of three girls growing up in New York, maturing in a world of baffling freedoms and uncertainties.... Childhood fears, passionate friendships, sexual explorations, and the uncomfortable interdependency of parents and children are depicted with intelligence, honesty, and dark humor. But if you are looking for comfort and consolation, you must look elsewhere: Tillman writes about life as it is, not as we might wish it to be." — Sunday Times

Lynne Tillman's writing uncovers hidden truths, reveals the unnamable, and leads us into her personal world of pain, pleasure, laughter, fear and confusion, with a clarity of style that is both remarkable and exhilarating. Honest. Simple. Deep. Authentic. Daring... To read her is, in a sense, to become alive, because she lives so thoroughly in her work. Lynne Tillman is, quite simply, one of the best writers alive today." — John Zorn

"Lynne Tillman's haunted houses are Freudian ones — the psyches of three girls, Emily, Jane, and Grace, each wrestling with the psychological 'ghosts' that shape them . . . . Frequently shifting points of view are expressed in crisp sentences. Rather than forming a modernist stream of consciousness, however, the writing remains controlled." — Lucy Atkins, Times Literary Supplement

Extras

From Chapter One:

At two she had tried to claim her father as her own, covering his face with her little body, and shouting, He's my daddy, my daddy, to her much older sisters, who could dismiss that kind of behavior as babyish. But Jane was driven. She became Daddy's girl to the chagrin of her mother, who had her hands full anyway. The third child is always the easiest, she heard her mother say to a woman who was visiting. It's like she's raising herself.

Jane's first boyfriend, when she was three, was a morose, skinny kid who lived on the floor below, his whole family skinny and very pale. After a pretend marriage that lasted a year, they were separated because her family moved away to the suburbs, and she asked one of her sisters if this meant they were divorced. Yes, she answered, and Jane promptly found a second boyfriend, Jimmy, who lived on the next block. He, too, was a peculiar boy, three years older than Jane, and elusive; she could never tell if he liked her or not. Jane couldn't figure out who her parents liked either, though her father said he liked everybody. In any case he was nice to everybody and they didn't see him when he was sulking in the basement because he couldn't hook up the speaker to the radio. He put a telephone down there, ostensibly to call his mother, who didn't get along with Jane’s mother, and he called her every day.

When she played. with Jimmy, Jane insisted upon wearing dresses. He's too wild, her mother told her. But his nostrils flare when he speaks, she responded, which meant to Jane that Jimmy was sensitive, like a rabbit. She could even tell him about the children’s book she loved and hated because it confused her. There was a little girl who had a

blanket. The blanket got a hole in it. She wanted to get rid of the hole so she decided to cut it out. She cut it out and the hole got bigger. She cut that out too, and the hole got bigger. Eventually the hole disappeared but so did the blanket. The little girl cried and Jane was genuinely puzzled.

An unspoken contract existed between Jane and her father; she went along to ball games and amusement parks when other fathers brought their sons. She played seriously with their sons, stretching across the slippery iron horse, reaching for the brass ring, though she was afraid of heights, reaching for it as if she really cared about winning. She hated losing her balance. Jane was almost certain that her father was her partner in this charade, and that he knew she was humoring him. But his moods changed as fast as she changed TV channels. He'd always been violent and had used his belt on Jane when she was small, but these violations were more than balanced by his good looks and charm. Her violations were almost invisible, something about the way she answered a question, something about the way she walked into a room. Everyone was in love with her father, Jane thought. He was so young-looking that her oldest sister's friends thought he looked more like her sister's date than her father.

He liked to read to his daughters. And he, more often than her mother, put Jane to bed at night. Occasionally he recited Churchill's memorable speech about blood, sweat, and tears, or read the Gettysburg Address, or cited the George Medal, which George VI had instituted for commoners, like her and him, to commend them for "obscure heroism in squalid places." But while he had read Shakespeare to her sisters, he chose for her Lord Chesterfield's Letters to his Son. Lord Chesterfield wrote many long and logical letters to his profligate son, who should have been in England, not France, of the great harm that would come to him should he continue gambling and shoring. These letters, like Churchill's speech, were supposed to comfort Jane, who had trouble sleeping at night, but as she was only eight when Chesterfield was read to her, she was not yet thinking of leaving home, or gambling, or whoring, or of being a whore, and unlike Chesterfield's son, she barely even had an allowance. These letters were harbingers of some future time and didn't comfort her. At their best they did put her to sleep. Jane never told her father not to read these letters to her. He might sulk or go into a rage. She became an Anglophile anyway.

Watching her oldest sister's boyfriends come and go, Jane acted like a lady-in-waiting to her—getting her brush, finding her bag, studying her image in the mirror. When her sister put on makeup, it looked to Jane as if she were preparing for a part in a play. There was a solemnness pervading the bathroom, mixed in with smells from the older girl's lipstick and powder and perfume with which she anointed herself. Glowing with artifice and anxiety, Jane's sister walked down the stairs, viewed by Jane at the top, lying fat on her stomach so that the boyfriend might not see. Then they disappeared, her sister and her date, both actors in another world.

By the time Jimmy announced that he loved her, or rather her shadow, which she knew meant her the fact that they were in different grades meant more to her than having won the attenuated battle for his affections. He was eleven and not as skinny as he'd once been, and even though his nostrils still quivered, he just wasn't as cute, she thought, so she pretended not to understand what he was saying, which was, she discovered early, a disguise that worked.

Besides, she had fallen in love with Michael, another bad boy from good people who couldn't control him, or that's what Jane's mother said. She usually added, He'll grow out of it, as if his character were a pair of pants. With Jane, Michael stole useless things from Woolworth's. She stole the tops of Dixie cups for him and watched with pleasure—a small smile on an otherwise impassive face—when Michael ripped birthday party decorations off basement walls. Jane never gave parties and hated basements, where they were always held. Her family's basement was used by her mother to do the laundry, her middle sister, to practice ballet, and by her father, less specifically. It had a ballet barre, a Ping-Pong table, and bookshelves in which her father paperbacks like How to Live with Your Anxiety and hardcovers about Winston Churchill and Abraham Lincoln. One Lincoln book had a picture of all the accomplices to his assassination, hanging on the gallows. Five wore trousers, and one, a dress. Their heads were covered with white bags. She stared at the image for long periods of time in the almost empty recreation room, the room itself weird joke to Jane, whose sense of humor was grim. Watching the conclusion of A Farewell to Arms on television with her mother, she said, flatly, He should get an erector set. Her mother laughed, despite herself, said nothing, and worried about Jane's strange ideas.

At two she had tried to claim her father as her own, covering his face with her little body, and shouting, He's my daddy, my daddy, to her much older sisters, who could dismiss that kind of behavior as babyish. But Jane was driven. She became Daddy's girl to the chagrin of her mother, who had her hands full anyway. The third child is always the easiest, she heard her mother say to a woman who was visiting. It's like she's raising herself.

Jane's first boyfriend, when she was three, was a morose, skinny kid who lived on the floor below, his whole family skinny and very pale. After a pretend marriage that lasted a year, they were separated because her family moved away to the suburbs, and she asked one of her sisters if this meant they were divorced. Yes, she answered, and Jane promptly found a second boyfriend, Jimmy, who lived on the next block. He, too, was a peculiar boy, three years older than Jane, and elusive; she could never tell if he liked her or not. Jane couldn't figure out who her parents liked either, though her father said he liked everybody. In any case he was nice to everybody and they didn't see him when he was sulking in the basement because he couldn't hook up the speaker to the radio. He put a telephone down there, ostensibly to call his mother, who didn't get along with Jane’s mother, and he called her every day.

When she played. with Jimmy, Jane insisted upon wearing dresses. He's too wild, her mother told her. But his nostrils flare when he speaks, she responded, which meant to Jane that Jimmy was sensitive, like a rabbit. She could even tell him about the children’s book she loved and hated because it confused her. There was a little girl who had a

blanket. The blanket got a hole in it. She wanted to get rid of the hole so she decided to cut it out. She cut it out and the hole got bigger. She cut that out too, and the hole got bigger. Eventually the hole disappeared but so did the blanket. The little girl cried and Jane was genuinely puzzled.

An unspoken contract existed between Jane and her father; she went along to ball games and amusement parks when other fathers brought their sons. She played seriously with their sons, stretching across the slippery iron horse, reaching for the brass ring, though she was afraid of heights, reaching for it as if she really cared about winning. She hated losing her balance. Jane was almost certain that her father was her partner in this charade, and that he knew she was humoring him. But his moods changed as fast as she changed TV channels. He'd always been violent and had used his belt on Jane when she was small, but these violations were more than balanced by his good looks and charm. Her violations were almost invisible, something about the way she answered a question, something about the way she walked into a room. Everyone was in love with her father, Jane thought. He was so young-looking that her oldest sister's friends thought he looked more like her sister's date than her father.

He liked to read to his daughters. And he, more often than her mother, put Jane to bed at night. Occasionally he recited Churchill's memorable speech about blood, sweat, and tears, or read the Gettysburg Address, or cited the George Medal, which George VI had instituted for commoners, like her and him, to commend them for "obscure heroism in squalid places." But while he had read Shakespeare to her sisters, he chose for her Lord Chesterfield's Letters to his Son. Lord Chesterfield wrote many long and logical letters to his profligate son, who should have been in England, not France, of the great harm that would come to him should he continue gambling and shoring. These letters, like Churchill's speech, were supposed to comfort Jane, who had trouble sleeping at night, but as she was only eight when Chesterfield was read to her, she was not yet thinking of leaving home, or gambling, or whoring, or of being a whore, and unlike Chesterfield's son, she barely even had an allowance. These letters were harbingers of some future time and didn't comfort her. At their best they did put her to sleep. Jane never told her father not to read these letters to her. He might sulk or go into a rage. She became an Anglophile anyway.

Watching her oldest sister's boyfriends come and go, Jane acted like a lady-in-waiting to her—getting her brush, finding her bag, studying her image in the mirror. When her sister put on makeup, it looked to Jane as if she were preparing for a part in a play. There was a solemnness pervading the bathroom, mixed in with smells from the older girl's lipstick and powder and perfume with which she anointed herself. Glowing with artifice and anxiety, Jane's sister walked down the stairs, viewed by Jane at the top, lying fat on her stomach so that the boyfriend might not see. Then they disappeared, her sister and her date, both actors in another world.

By the time Jimmy announced that he loved her, or rather her shadow, which she knew meant her the fact that they were in different grades meant more to her than having won the attenuated battle for his affections. He was eleven and not as skinny as he'd once been, and even though his nostrils still quivered, he just wasn't as cute, she thought, so she pretended not to understand what he was saying, which was, she discovered early, a disguise that worked.

Besides, she had fallen in love with Michael, another bad boy from good people who couldn't control him, or that's what Jane's mother said. She usually added, He'll grow out of it, as if his character were a pair of pants. With Jane, Michael stole useless things from Woolworth's. She stole the tops of Dixie cups for him and watched with pleasure—a small smile on an otherwise impassive face—when Michael ripped birthday party decorations off basement walls. Jane never gave parties and hated basements, where they were always held. Her family's basement was used by her mother to do the laundry, her middle sister, to practice ballet, and by her father, less specifically. It had a ballet barre, a Ping-Pong table, and bookshelves in which her father paperbacks like How to Live with Your Anxiety and hardcovers about Winston Churchill and Abraham Lincoln. One Lincoln book had a picture of all the accomplices to his assassination, hanging on the gallows. Five wore trousers, and one, a dress. Their heads were covered with white bags. She stared at the image for long periods of time in the almost empty recreation room, the room itself weird joke to Jane, whose sense of humor was grim. Watching the conclusion of A Farewell to Arms on television with her mother, she said, flatly, He should get an erector set. Her mother laughed, despite herself, said nothing, and worried about Jane's strange ideas.

Textul de pe ultima copertă

Praise for Lynne Tillman

"Lynne Tillman has always been a hero of mine—not because I 'admire' her writing, (although I do, very, very much), but because I feel it. Imagine driving alone at night. You turn on the radio and hear a song that seems to say it all. That's how I feel..." — Jonathan Safran Foer

"One of America's most challenging and adventurous writers." — Guardian

"Like an acupuncturist, Lynne Tillman knows the precise points in which to sink her delicate probes. One of the biggest problems in composing fiction is understanding what to leave out; no one is more severe, more elegant, more shocking in her reticences than Tillman." — Edmund White

“Anything I’ve read by Tillman I’ve devoured.” — Anne K. Yoder, The Millions

"If I needed to name a book that is maybe the most overlooked important piece of fiction in not only the 00s, but in the last 50 years, [American Genius, A Comedy] might be the one. I could read this back to back to back for years." — Blake Butler, HTML Giant

Notă biografică

Lynne Tillman (New York, NY) is the author of five novels, three collections of short stories, one collection of essays and two other nonfiction books. She collaborates often with artists and writes regularly on culture, and her fiction is anthologized widely. Her novels include American Genius, A Comedy (2006), No Lease on Life (1998) which was a New York Times Notable Book of 1998 and a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award, Cast in Doubt (1992), Motion Sickness (1991), and Haunted Houses (1987). The Broad Picture (1997) collected Tillman’s essays, which were published in literary and art periodicals. Her most recent book, Someday This Will Be Funny was a New York Times Editors Choice and an Oprah Summer Reading Pick. She is the Fiction Editor at Fence Magazine, Professor and Writer-in-Residence in the Department of English at the University at Albany, and a recent recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship.