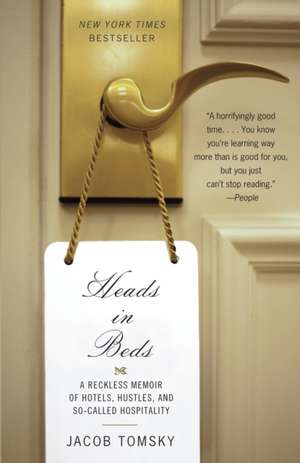

Heads in Beds: Anchor Books

Autor Jacob Tomskyen Limba Engleză Paperback – 29 iul 2013

Jacob Tomsky never intended to go into the hotel business. As a new college graduate, armed only with a philosophy degree and a singular lack of career direction, he became a valet parker for a large luxury hotel in New Orleans. Yet, rising fast through the ranks, he ended up working in “hospitality” for more than a decade, doing everything from supervising the housekeeping department to manning the front desk at an upscale Manhattan hotel. He’s checked you in, checked you out, separated your white panties from the white bed sheets, parked your car, tasted your room-service meals, cleaned your toilet, denied you a late checkout, given you a wake-up call, eaten M&Ms out of your minibar, laughed at your jokes, and taken your money. In Heads in Beds he pulls back the curtain to expose the crazy and compelling reality of a multi-billion-dollar industry we think we know.

Heads in Beds is a funny, authentic, and irreverent chronicle of the highs and lows of hotel life, told by a keenly observant insider who’s seen it all. Prepare to be amused, shocked, and amazed as he spills the unwritten code of the bellhops, the antics that go on in the valet parking garage, the housekeeping department’s dirty little secrets—not to mention the shameless activities of the guests, who are rarely on their best behavior. Prepare to be moved, too, by his candor about what it’s like to toil in a highly demanding service industry at the luxury level, where people expect to get what they pay for (and often a whole lot more). Employees are poorly paid and frequently abused by coworkers and guests alike, and maintaining a semblance of sanity is a daily challenge.

Along his journey Tomsky also reveals the secrets of the industry, offering easy ways to get what you need from your hotel without any hassle. This book (and a timely proffered twenty-dollar bill) will help you score late checkouts and upgrades, get free stuff galore, and make that pay-per-view charge magically disappear. Thanks to him you’ll know how to get the very best service from any business that makes its money from putting heads in beds. Or, at the very least, you will keep the bellmen from taking your luggage into the camera-free back office and bashing it against the wall repeatedly.

Din seria Anchor Books

-

Preț: 88.61 lei

Preț: 88.61 lei -

Preț: 80.88 lei

Preț: 80.88 lei -

Preț: 83.71 lei

Preț: 83.71 lei -

Preț: 72.23 lei

Preț: 72.23 lei -

Preț: 96.71 lei

Preț: 96.71 lei -

Preț: 108.42 lei

Preț: 108.42 lei -

Preț: 81.35 lei

Preț: 81.35 lei -

Preț: 89.50 lei

Preț: 89.50 lei -

Preț: 79.29 lei

Preț: 79.29 lei -

Preț: 89.37 lei

Preț: 89.37 lei -

Preț: 59.05 lei

Preț: 59.05 lei -

Preț: 112.40 lei

Preț: 112.40 lei -

Preț: 66.59 lei

Preț: 66.59 lei -

Preț: 128.89 lei

Preț: 128.89 lei - 13%

Preț: 98.11 lei

Preț: 98.11 lei -

Preț: 59.83 lei

Preț: 59.83 lei -

Preț: 71.23 lei

Preț: 71.23 lei -

Preț: 135.47 lei

Preț: 135.47 lei -

Preț: 93.82 lei

Preț: 93.82 lei -

Preț: 296.80 lei

Preț: 296.80 lei -

Preț: 141.06 lei

Preț: 141.06 lei -

Preț: 91.63 lei

Preț: 91.63 lei -

Preț: 50.53 lei

Preț: 50.53 lei -

Preț: 89.48 lei

Preț: 89.48 lei -

Preț: 74.49 lei

Preț: 74.49 lei -

Preț: 106.67 lei

Preț: 106.67 lei -

Preț: 111.51 lei

Preț: 111.51 lei - 16%

Preț: 79.33 lei

Preț: 79.33 lei -

Preț: 70.55 lei

Preț: 70.55 lei -

Preț: 88.89 lei

Preț: 88.89 lei -

Preț: 54.62 lei

Preț: 54.62 lei -

Preț: 64.09 lei

Preț: 64.09 lei -

Preț: 89.04 lei

Preț: 89.04 lei -

Preț: 92.60 lei

Preț: 92.60 lei -

Preț: 123.29 lei

Preț: 123.29 lei -

Preț: 91.38 lei

Preț: 91.38 lei - NaN%

Preț: 78.31 lei

Preț: 78.31 lei -

Preț: 144.11 lei

Preț: 144.11 lei -

Preț: 115.65 lei

Preț: 115.65 lei -

Preț: 91.64 lei

Preț: 91.64 lei -

Preț: 94.88 lei

Preț: 94.88 lei -

Preț: 75.94 lei

Preț: 75.94 lei -

Preț: 91.13 lei

Preț: 91.13 lei -

Preț: 135.88 lei

Preț: 135.88 lei -

Preț: 100.73 lei

Preț: 100.73 lei -

Preț: 91.55 lei

Preț: 91.55 lei -

Preț: 92.99 lei

Preț: 92.99 lei -

Preț: 89.06 lei

Preț: 89.06 lei

Preț: 81.66 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 122

Preț estimativ în valută:

15.63€ • 16.98$ • 13.14£

15.63€ • 16.98$ • 13.14£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307948342

ISBN-10: 030794834X

Pagini: 306

Dimensiuni: 133 x 202 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

Colecția Anchor Books

Seria Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 030794834X

Pagini: 306

Dimensiuni: 133 x 202 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

Colecția Anchor Books

Seria Anchor Books

Extras

Chapter One

I am standing on St. Charles Avenue, uptown New Orleans, a few months out of college and a few weeks into summer. It’s already extremely hot in the full sun. Which is where I have to stand: in the sun. Next to the valet box. All day.

I took a valet-parking job at Copeland’s restaurant to shake off my college-loan laziness, to climb out of the educational womb and stand on my own two feet as a moneymaking, career-pursuing adult. Educated in the useless and inapplicable field of philosophy, I quickly deduced that my degree looked slightly comical on my already light-on-the-work-experience résumé. Perhaps it was even off-putting. To a certain eye, hell, it probably made me look like a prick. But I had to start somewhere. So I started at the bottom.

This job is not good enough. Why not? First of all, I’m parking cars. Second, we have to turn in all our tips. I imagined I’d get off the first night with a pocketful of ones to take to the French Quarter, not that you need much money in New Orleans. As it turned out, however, attached to the valet box that houses the car keys, like a wooden tumor, is a separate slot for us to jimmy in our folded tips. All of them. Attached to that box, like a human tumor, is the shift boss, back in the shade at a vacant umbrella table, sipping a noontime drink that most definitely contains alcohol. It also has chipped ice and is sweating in his hand, sweating in a much different way than I am sweating.

A lunch customer hands me his ticket. I find his keys easily in the box and take off at an impressive run. His car is not easy to find: the valet company has not rented a nearby lot to service the restaurant, and so we, certainly unbeknownst to the clients, just drive around the area and try to parallel park the vehicles as close to Copeland’s as possible. Once the vehicle has been parked, it’s up to the valet to draw a silly treasure map on the back of the ticket so another valet can locate it. My co-worker Chip draws every treasure map like this: #*. Every single one. And finding the car is never easy. But I bring it back and slide up to the curb, holding the door open, the car’s AC pouring like ice water on my feet, and receive a neatly folded bill from the customer.

“It’s damn hot out here, son. This is for you running like that.”

It’s a twenty-dollar bill. Chip, now back and posted by the valet box, holds a salute against his brow, trying like hell to make out the bill. I walk up to the tip tumor and start to wiggle it in when Chip says, “No. No! What are you doing, Tommy? Don’t you keep a dollar handy to swap it out with? Please don’t put that twenty in there. Please. It’s for you. That dude told you it was for you.”

“Actually, it’s for Copeland’s Valet Parking Corporation,” the human tumor says, setting his drink down wet on the valet box.

“Are you seriously drinking a mudslide?” Chip asks.

I use a car key from the box to vanish the bill completely and post up next to Chip. Back in the sun. The shift boss sinks back into the shade.

“I am way too old for this. Sharing tips? Forty percent to management leaves 60 percent of the tips to us, divided over twenty runners, on a check, with taxes taken out, and guess who’s running the math, guess who’s counting up the tips? A grown man drinking a goddamn mudslide.” He must have been talking to himself previously because now Chip turned to me: “You think he’s gonna turn in that twenty? Or just keep it for himself? We never get good tips out here. You know what I heard? There’s a new hotel opening up downtown. You heard that? It’s supposed to be luxury.” He said the word as if it were mystical and perhaps too good for his own tongue: “luxury.” “And they’re looking for parkers. Copeland’s customers don’t tip for shit.”

Chip, with a wide smile, accepts a claim check from an emerging lunch customer and locates the keys in the box. “It’s a fucking Mazda, dude,” he says quietly to me. And then to the customer: “You won’t be long in this heat, sir! I will run for your vehicle!” Then he takes off sprinting: it’s almost vaudevillian how he tears ass around the corner, his body at full tilt.

Chip cruises the Mazda back in record time, gliding up to the curb. “AC running and classic rock on low for you, sir.”

The customer drops something into his cupped palm. Something that makes Chip’s face contort.

Chip stands upright, essentially blocking the customer from entering his own vehicle, and spreads open his palm to let the two-quarter tip flash in the sun.

With a voice strained and tight, as if he were suffering intense physical pain, he says, “Why, thank you so very much, sir.”

Then he pivots slightly and extends his hand, palm flat, quarters in the sun again.

Then he drop-kicks both coins. Kicks the shit out of them into the street.

They arc over the road and land on the rough grass of the neutral ground, settling in before a streetcar rocks by.

I can see the shock on the customer’s face—the confusion, the horror. Chip just walks off with determination, crossing St. Charles and onto the neutral ground. After picking the quarters out of the grass, he crosses the tracks to the far side of the street and starts bearing down Napoleon Avenue, toward Mid-City: the job, the restaurant, the shift boss, me, all of us in his rearview mirror.

I finished my shift. Then I took his advice about the hotel job.

Whether I knew it yet or not, it was one hell of an important moment for me, watching Chip snap at what seemed like such a minor affront, seeing that much emotion applied to a single low-quality tip. And then watching him bend down, fish the quarters out of the dirt, and take them with him. I didn’t understand any of it. Not yet.

Here we go.

Hotel orientation. Human resources pretty much hired everyone. Everyone who passed the drug test.

I passed, thank you.

Chip did not.

The River Hotel, connected to a brand known for luxury, known for being out of almost everyone’s price range, was being built right there on Chartres Street, in downtown New Orleans. It was three weeks from opening and still under construction. Yet they hired us all, tailored our uniforms, and started paying us. A week ago I was earning money and giving it to an idiot who pounds mudslides. Now I wasn’t even working, but I was collecting a check. A good check. And no one had even said the word “valet” yet.

Not that our new managers weren’t saying any words. Honestly, they couldn’t stop saying some words: “Service.” “Luxury.” “Honesty.” “Loyalty.” “Opulence.” And mid-length phrases such as “Customer Feedback” and “Anticipating Needs.” And then longer, million-dollar phrases like “Fifteen-Hundred-Thread-Count Egyptian Linen Duvet Covers.”

Management ran classes every day on service, administered in the completed conference rooms, the tables draped with what we assumed to be Egyptian fabric and adorned with iced carafes of water, which we poured into crystal goblets to wash down the huge piles of pastries they fed us. They were hell-bent on teaching us how to identify something called “a guest’s unmentioned needs.”

“A man needs his car, he don’t need to speak a word. Get that claim check out. Get that dollar out, feel me?”

That came from the back of class. I turned my head to get a look at who I assumed were to be my co-workers: three black guys not really adhering to the “business casual” mandate for these orientation classes.

“Tommy, can you give me an example of a guest’s unmentioned need?”

I wasn’t even wearing a name badge: these hospitality maniacs had actually learned everyone’s name.

“Well, ma’am—”

“You can call me Trish. I’m the front office manager.”

“Well, ah, Trish . . .” That got a low laugh from the back of class. “Maybe they pull in a car, it’s dirty from the drive, and we could get it washed?”

“Perfect example.”

“Wait up. You want I should drive the car back to my driveway in the Ninth Ward to wash it? Or bring in quarters from home?”

“Perry; correct?”

“Yeah, Perry.”

“Perry. You come to me anytime, and I’ll give you hotel money to wash a car, change a tire, or buy them a CD you know they’d like for the drive home. Anything you think of, you can come to me.”

“Well, goddamn.”

The day before the grand opening the hotel closed off a block of Chartres Street (pronounced “Chart-ers,” by the way, completely disregarding the obvious Frenchness of the word; we also pronounce the street Calliope like “Cal-e-ope”; Burgundy comes out not like the color but “Ber-GUN-dy,” and just try to stutter out Tchoupitoulas Street or Natchitoches even close to correctly). We were collected into parade groups, our new managers holding up large, well-made signs indicating our departments. Front desk. Valet. Laundry. Sales and marketing. Bellmen. Doormen. Food and beverage. And housekeeping of course, by far the largest group, about 150 black ladies dressed as if they were going to a club. The valets hung together in a small clot, not saying much to each other, looking up at the finished, renovated hotel.

The vibe was celebratory and overwhelmingly positive. We were let in, one department after the other, and we hustled up a stairwell lined with managers clapping and cheering as if we were the goddamn New Orleans Saints. They threw confetti, smacked us on the back, and screamed in an orgy of goodwill and excitement. By the time we crested the third floor and poured into the grand banquet hall, every single one of us had huge, marvelously sincere smiles stuck hard on our faces. And we held those smiles as we took turns shaking the general manager’s hand, who, no shit, wore a crown of laurel leaves. As a joke, I suppose.

“I’m Charles Daniels. Please, call me Chuck.”

“All right, then, Chuck,” Perry said in front of me and waited while Mr. Daniels located the gold-plated name tag that read “Perry” from the banquet table beside him.

Mr. Daniels didn’t go so far as to pin on the name tag, anoint us, as it were. But we were in such a rapturous state during the event I believe we would have readily kneeled before him and let him pin it to our naked flesh.

And then there was an open bar. Not sure where they shipped in this opening team from; they certainly weren’t locals. Neither was I, but I’d spent my young life traveling, moving so often I’d learned the skill (and believe me it is an incredibly useful skill) of assimilating into any new culture, whatever that culture may be. I am a shape-shifter in that way. And as I approached my four-year anniversary in Louisiana, just about my longest stretch anywhere, New Orleans had already become the closest thing to a home I’d ever had. And the open bar was a nod to this town, a town that runs on alcohol, and much appreciated. This is a city where you can find drink specials on Christmas morning. Not that you could find me on Bourbon Street Christmas morning; I didn’t drink at the time. I stayed sober all through college while pursuing my degree and hadn’t had a drop since I was fifteen and used to take shots of Jack Daniel’s in my basement during school lunch. But an open bar in New Orleans? People got tore up. Housekeeping got tore up.

Now that it was revealed which department we fell into, we tended to group up for the party, getting to know each other.

“Dig this general manager. He look like a slave owner with that headpiece,” Walter said.

“Nah,” Perry said. “Chuck a cool motherfucker. You just enjoy that free drink you got,” and then he took a long finishing pull from his own bottle of Heineken.

Everyone was smiling. Everyone was friendly. Everyone had a name tag on. It was like a big crazy family, and we opened tomorrow. We were all in this together, and everyone in that banquet hall, after two weeks of service training, two full paychecks for nothing, couldn’t wait to unleash their skills on a real guest. The managers had whipped us into such a frenzy that if any actual guests had wandered into that party, we would have serviced them to death, mauled them, like ravenous service jackals.

Already the hotel had created the possibility of a home for me, a future. It seemed so glamorous, all the linens and chandeliers and sticky pastries. The hotel was beautiful, and I was honored to be a member of the opening team. It was at this very point I realized my life of constant relocation had led me to this nexus of relocation, this palace of the temporal where I could now stand still, the world moving around me, and, conversely, feel grounded. I studied Mr. Daniels as he circulated the party, all conversation politely cutting off when he unobtrusively joined a group. That was the position I wanted. That was a life I could own. And I distinctly felt, because this is exactly what they told us during orientation, that if I performed with dedication and dignity, took the tenets of luxury service to heart, hospitality would open herself up to me and I could find my life within the industry. I wanted to be king. It was possible to be king. I swore that day I’d be the general manager of my very own property.

This excitement carried over and crashed like a wave on the following day, the day the hotel opened. But before we were able to molest our first guest, we had to sit through the opening ceremony.

One thing about hotels: once they open, they never close.

I don’t mean they never go out of business; certainly they do. But the fact that a hotel could fail to be profitable astounds me. Why? The average cost to turn over a room, keep it operational per day, is between thirty and forty dollars. If you’re paying less than thirty dollars a night at a hotel/motel, I’d wager the cost to flip that room runs close to five dollars. Which makes me want to take a shower. At home. That forty-dollar turnover cost includes cleaning supplies, electricity, and hourly wage for housekeepers, minibar attendants, front desk agents (and all other employees needed to operate a room), as well as the cost of laundering the sheets. Everything. Compare that with an average room rate, and you can see why it’s a profitable business, one with a long history, going back to Mary and Joseph running up against a sold-out situation at the inn, forcing him to bed his pregnant wife in a dirty-ass manger.

The word “hotel” itself was appropriated from the French around 1765. Across the ocean, a hotel, or hôtel, referred not to public lodging but instead to a large government building, the house of a nobleman, or any such place where people gathered but no nightly accommodation was offered. America, at the time, was filled with grimy little inns and taverns, which provided beds for travelers and also functioned as a town’s shitty dive bar. Having a monopoly on the alcohol game was a boon, one given to tavern keepers in gratitude for putting up travelers, something no one wanted any part of. It wasn’t until George Washington decided to embark on the first presidential tour of his new kingdom that spotlights began to shine on these public houses of grossness. In order to present himself as a man of the people, he turned down offers to stay with associates and wealthy friends, instead lodging himself in tavern after tavern, sniffing at room after room, frowning at bed after bed. For the first time in American history, townships were ashamed of their manner of accommodating travelers. The country was unified and expanding. Something had to be done about our system of lodging.

So, in 1794, someone, some asshole, built the very first “hotel” in New York City: a 137-room job on Broadway, right there in lower Manhattan. It was the first structure built with the intention of being a “hotel,” a word that was quickly replacing the terms “inn” and “tavern,” even if it only meant that swarthy innkeepers were painting the word “Hotel” onto their crappy signs but still sloshing out the booze and making travelers sleep right next to each other in bug-ridden squalor. The first big hotels failed monetarily or burned to the ground or both. It wasn’t until railroad lines were getting stitched across America’s expanding fabric that hotels, big and small, began to prosper and offer people like me jobs.

So, profitability aside, what I am referring to here is not the fact that once a hotel opens it will never close (or be burned to the ground!) but that once we cut the ribbon on the hotel, once we opened the lobby doors, they never closed again. In fact, they unchained them because they were built without locks, as almost all hotel lobby doors are. Three o’clock in the morning—open. Christmas Eve, 3:00 a.m.—open. Blackout—open. World War Whatever—open (with a price hike).

The mayor was kind enough to attend the opening ceremony, going down the line of sharp-dressed employees and shaking hands (or giving elaborate daps, depending on ethnicity). And then in came the public, and there we stood, smiling, proud, ready. The locals poured into the Bistro Lounge, strolled through the lobby as if it were a museum of classical art, put handprints on fresh glass doors, and began to scuff, mark, and mar the pristine landscape, putting their asses in chairs, creasing and bending the leather, scraping and marking the cutlery as they bit down hard on steak-tipped forks.

For a long while at the valet stand, well, we didn’t have shit to do. We stood those first few hours, feet spread and planted at shoulder width, arms behind our backs with our hands clasped, as we were taught to stand. Then we began to shift on our feet. Then we began to talk quietly out of the sides of our mouths. Then to turn our heads and talk openly at a normal volume. Then to go to the back office to check our cell phones. Not Perry, though: he remained at his post, and the most he did was shake his head when everyone started to get restless.

I am standing on St. Charles Avenue, uptown New Orleans, a few months out of college and a few weeks into summer. It’s already extremely hot in the full sun. Which is where I have to stand: in the sun. Next to the valet box. All day.

I took a valet-parking job at Copeland’s restaurant to shake off my college-loan laziness, to climb out of the educational womb and stand on my own two feet as a moneymaking, career-pursuing adult. Educated in the useless and inapplicable field of philosophy, I quickly deduced that my degree looked slightly comical on my already light-on-the-work-experience résumé. Perhaps it was even off-putting. To a certain eye, hell, it probably made me look like a prick. But I had to start somewhere. So I started at the bottom.

This job is not good enough. Why not? First of all, I’m parking cars. Second, we have to turn in all our tips. I imagined I’d get off the first night with a pocketful of ones to take to the French Quarter, not that you need much money in New Orleans. As it turned out, however, attached to the valet box that houses the car keys, like a wooden tumor, is a separate slot for us to jimmy in our folded tips. All of them. Attached to that box, like a human tumor, is the shift boss, back in the shade at a vacant umbrella table, sipping a noontime drink that most definitely contains alcohol. It also has chipped ice and is sweating in his hand, sweating in a much different way than I am sweating.

A lunch customer hands me his ticket. I find his keys easily in the box and take off at an impressive run. His car is not easy to find: the valet company has not rented a nearby lot to service the restaurant, and so we, certainly unbeknownst to the clients, just drive around the area and try to parallel park the vehicles as close to Copeland’s as possible. Once the vehicle has been parked, it’s up to the valet to draw a silly treasure map on the back of the ticket so another valet can locate it. My co-worker Chip draws every treasure map like this: #*. Every single one. And finding the car is never easy. But I bring it back and slide up to the curb, holding the door open, the car’s AC pouring like ice water on my feet, and receive a neatly folded bill from the customer.

“It’s damn hot out here, son. This is for you running like that.”

It’s a twenty-dollar bill. Chip, now back and posted by the valet box, holds a salute against his brow, trying like hell to make out the bill. I walk up to the tip tumor and start to wiggle it in when Chip says, “No. No! What are you doing, Tommy? Don’t you keep a dollar handy to swap it out with? Please don’t put that twenty in there. Please. It’s for you. That dude told you it was for you.”

“Actually, it’s for Copeland’s Valet Parking Corporation,” the human tumor says, setting his drink down wet on the valet box.

“Are you seriously drinking a mudslide?” Chip asks.

I use a car key from the box to vanish the bill completely and post up next to Chip. Back in the sun. The shift boss sinks back into the shade.

“I am way too old for this. Sharing tips? Forty percent to management leaves 60 percent of the tips to us, divided over twenty runners, on a check, with taxes taken out, and guess who’s running the math, guess who’s counting up the tips? A grown man drinking a goddamn mudslide.” He must have been talking to himself previously because now Chip turned to me: “You think he’s gonna turn in that twenty? Or just keep it for himself? We never get good tips out here. You know what I heard? There’s a new hotel opening up downtown. You heard that? It’s supposed to be luxury.” He said the word as if it were mystical and perhaps too good for his own tongue: “luxury.” “And they’re looking for parkers. Copeland’s customers don’t tip for shit.”

Chip, with a wide smile, accepts a claim check from an emerging lunch customer and locates the keys in the box. “It’s a fucking Mazda, dude,” he says quietly to me. And then to the customer: “You won’t be long in this heat, sir! I will run for your vehicle!” Then he takes off sprinting: it’s almost vaudevillian how he tears ass around the corner, his body at full tilt.

Chip cruises the Mazda back in record time, gliding up to the curb. “AC running and classic rock on low for you, sir.”

The customer drops something into his cupped palm. Something that makes Chip’s face contort.

Chip stands upright, essentially blocking the customer from entering his own vehicle, and spreads open his palm to let the two-quarter tip flash in the sun.

With a voice strained and tight, as if he were suffering intense physical pain, he says, “Why, thank you so very much, sir.”

Then he pivots slightly and extends his hand, palm flat, quarters in the sun again.

Then he drop-kicks both coins. Kicks the shit out of them into the street.

They arc over the road and land on the rough grass of the neutral ground, settling in before a streetcar rocks by.

I can see the shock on the customer’s face—the confusion, the horror. Chip just walks off with determination, crossing St. Charles and onto the neutral ground. After picking the quarters out of the grass, he crosses the tracks to the far side of the street and starts bearing down Napoleon Avenue, toward Mid-City: the job, the restaurant, the shift boss, me, all of us in his rearview mirror.

I finished my shift. Then I took his advice about the hotel job.

Whether I knew it yet or not, it was one hell of an important moment for me, watching Chip snap at what seemed like such a minor affront, seeing that much emotion applied to a single low-quality tip. And then watching him bend down, fish the quarters out of the dirt, and take them with him. I didn’t understand any of it. Not yet.

Here we go.

Hotel orientation. Human resources pretty much hired everyone. Everyone who passed the drug test.

I passed, thank you.

Chip did not.

The River Hotel, connected to a brand known for luxury, known for being out of almost everyone’s price range, was being built right there on Chartres Street, in downtown New Orleans. It was three weeks from opening and still under construction. Yet they hired us all, tailored our uniforms, and started paying us. A week ago I was earning money and giving it to an idiot who pounds mudslides. Now I wasn’t even working, but I was collecting a check. A good check. And no one had even said the word “valet” yet.

Not that our new managers weren’t saying any words. Honestly, they couldn’t stop saying some words: “Service.” “Luxury.” “Honesty.” “Loyalty.” “Opulence.” And mid-length phrases such as “Customer Feedback” and “Anticipating Needs.” And then longer, million-dollar phrases like “Fifteen-Hundred-Thread-Count Egyptian Linen Duvet Covers.”

Management ran classes every day on service, administered in the completed conference rooms, the tables draped with what we assumed to be Egyptian fabric and adorned with iced carafes of water, which we poured into crystal goblets to wash down the huge piles of pastries they fed us. They were hell-bent on teaching us how to identify something called “a guest’s unmentioned needs.”

“A man needs his car, he don’t need to speak a word. Get that claim check out. Get that dollar out, feel me?”

That came from the back of class. I turned my head to get a look at who I assumed were to be my co-workers: three black guys not really adhering to the “business casual” mandate for these orientation classes.

“Tommy, can you give me an example of a guest’s unmentioned need?”

I wasn’t even wearing a name badge: these hospitality maniacs had actually learned everyone’s name.

“Well, ma’am—”

“You can call me Trish. I’m the front office manager.”

“Well, ah, Trish . . .” That got a low laugh from the back of class. “Maybe they pull in a car, it’s dirty from the drive, and we could get it washed?”

“Perfect example.”

“Wait up. You want I should drive the car back to my driveway in the Ninth Ward to wash it? Or bring in quarters from home?”

“Perry; correct?”

“Yeah, Perry.”

“Perry. You come to me anytime, and I’ll give you hotel money to wash a car, change a tire, or buy them a CD you know they’d like for the drive home. Anything you think of, you can come to me.”

“Well, goddamn.”

The day before the grand opening the hotel closed off a block of Chartres Street (pronounced “Chart-ers,” by the way, completely disregarding the obvious Frenchness of the word; we also pronounce the street Calliope like “Cal-e-ope”; Burgundy comes out not like the color but “Ber-GUN-dy,” and just try to stutter out Tchoupitoulas Street or Natchitoches even close to correctly). We were collected into parade groups, our new managers holding up large, well-made signs indicating our departments. Front desk. Valet. Laundry. Sales and marketing. Bellmen. Doormen. Food and beverage. And housekeeping of course, by far the largest group, about 150 black ladies dressed as if they were going to a club. The valets hung together in a small clot, not saying much to each other, looking up at the finished, renovated hotel.

The vibe was celebratory and overwhelmingly positive. We were let in, one department after the other, and we hustled up a stairwell lined with managers clapping and cheering as if we were the goddamn New Orleans Saints. They threw confetti, smacked us on the back, and screamed in an orgy of goodwill and excitement. By the time we crested the third floor and poured into the grand banquet hall, every single one of us had huge, marvelously sincere smiles stuck hard on our faces. And we held those smiles as we took turns shaking the general manager’s hand, who, no shit, wore a crown of laurel leaves. As a joke, I suppose.

“I’m Charles Daniels. Please, call me Chuck.”

“All right, then, Chuck,” Perry said in front of me and waited while Mr. Daniels located the gold-plated name tag that read “Perry” from the banquet table beside him.

Mr. Daniels didn’t go so far as to pin on the name tag, anoint us, as it were. But we were in such a rapturous state during the event I believe we would have readily kneeled before him and let him pin it to our naked flesh.

And then there was an open bar. Not sure where they shipped in this opening team from; they certainly weren’t locals. Neither was I, but I’d spent my young life traveling, moving so often I’d learned the skill (and believe me it is an incredibly useful skill) of assimilating into any new culture, whatever that culture may be. I am a shape-shifter in that way. And as I approached my four-year anniversary in Louisiana, just about my longest stretch anywhere, New Orleans had already become the closest thing to a home I’d ever had. And the open bar was a nod to this town, a town that runs on alcohol, and much appreciated. This is a city where you can find drink specials on Christmas morning. Not that you could find me on Bourbon Street Christmas morning; I didn’t drink at the time. I stayed sober all through college while pursuing my degree and hadn’t had a drop since I was fifteen and used to take shots of Jack Daniel’s in my basement during school lunch. But an open bar in New Orleans? People got tore up. Housekeeping got tore up.

Now that it was revealed which department we fell into, we tended to group up for the party, getting to know each other.

“Dig this general manager. He look like a slave owner with that headpiece,” Walter said.

“Nah,” Perry said. “Chuck a cool motherfucker. You just enjoy that free drink you got,” and then he took a long finishing pull from his own bottle of Heineken.

Everyone was smiling. Everyone was friendly. Everyone had a name tag on. It was like a big crazy family, and we opened tomorrow. We were all in this together, and everyone in that banquet hall, after two weeks of service training, two full paychecks for nothing, couldn’t wait to unleash their skills on a real guest. The managers had whipped us into such a frenzy that if any actual guests had wandered into that party, we would have serviced them to death, mauled them, like ravenous service jackals.

Already the hotel had created the possibility of a home for me, a future. It seemed so glamorous, all the linens and chandeliers and sticky pastries. The hotel was beautiful, and I was honored to be a member of the opening team. It was at this very point I realized my life of constant relocation had led me to this nexus of relocation, this palace of the temporal where I could now stand still, the world moving around me, and, conversely, feel grounded. I studied Mr. Daniels as he circulated the party, all conversation politely cutting off when he unobtrusively joined a group. That was the position I wanted. That was a life I could own. And I distinctly felt, because this is exactly what they told us during orientation, that if I performed with dedication and dignity, took the tenets of luxury service to heart, hospitality would open herself up to me and I could find my life within the industry. I wanted to be king. It was possible to be king. I swore that day I’d be the general manager of my very own property.

This excitement carried over and crashed like a wave on the following day, the day the hotel opened. But before we were able to molest our first guest, we had to sit through the opening ceremony.

One thing about hotels: once they open, they never close.

I don’t mean they never go out of business; certainly they do. But the fact that a hotel could fail to be profitable astounds me. Why? The average cost to turn over a room, keep it operational per day, is between thirty and forty dollars. If you’re paying less than thirty dollars a night at a hotel/motel, I’d wager the cost to flip that room runs close to five dollars. Which makes me want to take a shower. At home. That forty-dollar turnover cost includes cleaning supplies, electricity, and hourly wage for housekeepers, minibar attendants, front desk agents (and all other employees needed to operate a room), as well as the cost of laundering the sheets. Everything. Compare that with an average room rate, and you can see why it’s a profitable business, one with a long history, going back to Mary and Joseph running up against a sold-out situation at the inn, forcing him to bed his pregnant wife in a dirty-ass manger.

The word “hotel” itself was appropriated from the French around 1765. Across the ocean, a hotel, or hôtel, referred not to public lodging but instead to a large government building, the house of a nobleman, or any such place where people gathered but no nightly accommodation was offered. America, at the time, was filled with grimy little inns and taverns, which provided beds for travelers and also functioned as a town’s shitty dive bar. Having a monopoly on the alcohol game was a boon, one given to tavern keepers in gratitude for putting up travelers, something no one wanted any part of. It wasn’t until George Washington decided to embark on the first presidential tour of his new kingdom that spotlights began to shine on these public houses of grossness. In order to present himself as a man of the people, he turned down offers to stay with associates and wealthy friends, instead lodging himself in tavern after tavern, sniffing at room after room, frowning at bed after bed. For the first time in American history, townships were ashamed of their manner of accommodating travelers. The country was unified and expanding. Something had to be done about our system of lodging.

So, in 1794, someone, some asshole, built the very first “hotel” in New York City: a 137-room job on Broadway, right there in lower Manhattan. It was the first structure built with the intention of being a “hotel,” a word that was quickly replacing the terms “inn” and “tavern,” even if it only meant that swarthy innkeepers were painting the word “Hotel” onto their crappy signs but still sloshing out the booze and making travelers sleep right next to each other in bug-ridden squalor. The first big hotels failed monetarily or burned to the ground or both. It wasn’t until railroad lines were getting stitched across America’s expanding fabric that hotels, big and small, began to prosper and offer people like me jobs.

So, profitability aside, what I am referring to here is not the fact that once a hotel opens it will never close (or be burned to the ground!) but that once we cut the ribbon on the hotel, once we opened the lobby doors, they never closed again. In fact, they unchained them because they were built without locks, as almost all hotel lobby doors are. Three o’clock in the morning—open. Christmas Eve, 3:00 a.m.—open. Blackout—open. World War Whatever—open (with a price hike).

The mayor was kind enough to attend the opening ceremony, going down the line of sharp-dressed employees and shaking hands (or giving elaborate daps, depending on ethnicity). And then in came the public, and there we stood, smiling, proud, ready. The locals poured into the Bistro Lounge, strolled through the lobby as if it were a museum of classical art, put handprints on fresh glass doors, and began to scuff, mark, and mar the pristine landscape, putting their asses in chairs, creasing and bending the leather, scraping and marking the cutlery as they bit down hard on steak-tipped forks.

For a long while at the valet stand, well, we didn’t have shit to do. We stood those first few hours, feet spread and planted at shoulder width, arms behind our backs with our hands clasped, as we were taught to stand. Then we began to shift on our feet. Then we began to talk quietly out of the sides of our mouths. Then to turn our heads and talk openly at a normal volume. Then to go to the back office to check our cell phones. Not Perry, though: he remained at his post, and the most he did was shake his head when everyone started to get restless.

Notă biografică

Jacob Tomsky is a dedicated veteran of the hospitality business. Well-spoken, uncannily quick on his feet, and no more honest than he needs to be, he also is the founder and president of Short Story Thursdays, a weekly, email based short story club. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, O Magazine, The Daily Beast, and other venues. Born in Oakland, California, to a military family, Tomsky now lives in Brooklyn, New York.

www.jacobtomsky.com

www.jacobtomsky.com

Recenzii

Praise for Heads in Beds:

"Heads in Beds is Mr. Tomsky’s highly amusing guidebook to the dirty little secrets of the hospitality trade. But it is neither a meanspirited book nor a one-sided one.... [H]e winds up sounding like an essentially honest, decent guy. And his observations about character are keen, perhaps because he’s seen it all.... If this were simply a travel book of the news-you-can-use ilk, it would be of only minor interest. But Mr. Tomsky turns out to be an effervescent writer, with enough snark to make his stories sharp-edged but without the self-promoting smugness that sinks so many memoirs.... Heads in Beds embraces the full, novelistic breadth of hotel experience.... [Tomsky] is no longer a hotel employee and now, with good reason, thinks of himself as a writer."

—Janet Maslin, New York Times

"For those of us who'd rather live in good hotels than in our own homes, oh Lordy, is this ever a horrifyingly good time. It's the sort of equivalent of WebMD for hypochondriacs: You know you're learning way more than is good for you, but you just can't stop reading. Tomsky, who may be an even better writer than a hotelier (and he's a damn good hotelier) has worked every job and every shift; he takes us into the bowels (sometimes literally) of the hotel business, with all the pomp and circumstance, the hidden filth, and the fears and aspirations and secrets of guests and staff alike."—Judith Newman, People (4 Stars)

"For the uninitiated, staying at a luxury hotel can be a little intimidating.... [But] front desk raconteur Jacob Tomsky is here to help. His sharp-witted, candid new book, Heads in Beds, demystifies the world of high-end hospitality.... Coarse, smart and wickedly funny, the author delivers hilarious caricatures of the hotel guests and colleagues he has encountered over the years.... Tightly written and laced with delicious insider tips."—John Wilwol, Washington Post

"A wonderfully indiscreet veteran of the hospitality industry, Jacob Tomsky knows his way around a hotel."—PARADE

"Room upgrades. Free movies. Late checkouts. Jacob Tomsky promises readers the keys to the hotel industry kingdom in his tell-all book, Heads in Beds. The one-time philosophy major has spent more than a decade working in the industry and, like room service, he delivers the goods.... Beyond tips, Tomsky has packed his book with outrageous anecdotes about guests...[and] the hotel staff too.... Tomsky has only worked at hotels in New Orleans and New York, so readers may wonder if his tips will work anywhere else. Maybe they will, maybe they won’t. But his stories are so good, it almost doesn’t matter."—Jessica Gresko, Associated Press

“Jacob Tomsky is a star. The kid writes like a dream. Heads in Beds is hilarious, literate, canny, indignant and kind—revealing an author who manages somehow to be both a total hustler and a complete humanitarian. I love this book. Keep an eye on this writer. I’m telling you, he’s a star.”

—Elizabeth Gilbert, author of Eat, Pray, Love: One Woman's Search for Everything Across Italy, India and Indonesia

“And I thought I had it bad when I worked in restaurants! Heads in Beds is a hilarious, informative, and naughty peek at what really happens behind the glitz and glamour of the hotel experience. Not content with dispensing advice on how to get a better room or avoiding the vengeful wrath of bellhops, maids, doormen, and front-desk clerks, Tomsky also spins a touching yarn on how he kept his dignity and humanity intact while dealing with insufferable guests, Expedia wannabes, predatory hotel managers, conniving coworkers, and the occasional pervert. After reading this book, you’ll become either a better-educated hotel guest who constantly receives great service—or realize why you always get that noisy room by the elevator shaft. As a survivor of America’s dysfunctional hospitality industry, I highly recommend this book.”

—Steve Dublanica, author of the New York Times bestseller Waiter Rant

“In pulling the musty curtains back on the seedy hotel business, Heads in Beds provides first-rate insights for all grades of travelers. But the real revelation here is Jacob Tomsky, whose writing combines presidential suite talent with rack-rate, smoking-room, vending-machine-down-the-hall edge.”

—Chuck Thompson, author of Smile When You’re Lying: Confessions of a Rogue Travel Writer

"Readable and often engaging.... [W]hen the author is passionate about his career and is able to express his passion on the page, it can be a joy to read... hilarious."—Kirkus Reviews

"Comparisons to Anthony Bourdain’s Kitchen Confidential (2000) are inevitable…. [B]oth Tomsky and Bourdain purport to expose the underbelly of service industries with which most readers are familiar, hotels and restaurants. But where Bourdain is all rock ’n’ roll, egotistical bluster, Tomsky is surprisingly earnest and sympathetic; there are, after all, no television programs called Top Desk Clerk. He wants your respect, not your adulation…. Indeed, it would be easy to pen a book about crazy hotel guests. But this memoir succeeds, instead, in humanizing the people who park our cars, clean our hotel rooms, and carry our luggage. You will never not tip housekeeping or your bellhop again. Tomsky fell into hotel work and proved to be rather good at it; the same can be said for his writing."—Booklist

"Those who want a hotel up-grade, who must make a same-day room cancellation without getting charged, or wonder why hotel water sometimes tastes like lemon Pledge need look no further than Tomsky's memoir, a collection of stories, memories, and secrets about the hospitality business. Bouncing around various hotel jobs...for more than 10 years, he's got the skinny that would make most travel sites blush.... But this is more than a collection of trade secrets; it's a colorful tale filled with vibrant characters from crazy bellmen to even crazier guests. Tomsky is a solid storyteller who is able to intricately detail all the insanity surrounding him."—Publishers Weekly

"With incredibly witty, from-the-gut prose, Mr. Tomsky provides an inside scoop on the good, the bad, and the incredibly ugly happenings that go on behind closed hotel doors—as well as front desk antics that happen right before your untrained, naïve eyes.... A very fun, entertaining read. It is incredibly relatable, not only for a consumer, but also for anyone who has worked in a public-oriented service industry. Despite his brash language, or perhaps in spite of it, the author comes across as sincere and personable with the patience of a saint—or at least he’s really good at faking it. Though it seems he was very good at this job, it’s about time for Jacob Tomsky to move on to bigger and better things. If this book is any indication, writing will be his next calling."—Renee C. Fountain, New York Journal of Books

"Tomsky shines in...this funny and profane memoir."—Nathan Gelgud, Biographile

"After the party, it’s the hotel lobby…. and that’s where things get real. Jacob Tomsky’s hilariously irreverent memoir Heads in Beds chronicles the all-work, no-sleep, but never dull lifestyle of the young hotelier and the innermost workings of high-end hotels...[and] shares five-star advice for your next check-in."—Gina Angelotti, Metro

"Heads in Beds is at turns hilarious, sad, too revealing, naughty, frightening and wildly fun. Tomsky proves to be a smart writer. His voice is warm and accessible, but he's also pleasantly snarky and potty-mouthed. He lets the reader see him at his smarmy, smooth-operating best and his filthy, fed-up worst. (And the book includes lots of tips, like how to eat and drink everything in your minibar for free, how to get extra amenities, and all of the things a hotel guest should never say to a front desk agent.)"—Alli Marshall, Mountain Xpress

"Heads in Beds is Mr. Tomsky’s highly amusing guidebook to the dirty little secrets of the hospitality trade. But it is neither a meanspirited book nor a one-sided one.... [H]e winds up sounding like an essentially honest, decent guy. And his observations about character are keen, perhaps because he’s seen it all.... If this were simply a travel book of the news-you-can-use ilk, it would be of only minor interest. But Mr. Tomsky turns out to be an effervescent writer, with enough snark to make his stories sharp-edged but without the self-promoting smugness that sinks so many memoirs.... Heads in Beds embraces the full, novelistic breadth of hotel experience.... [Tomsky] is no longer a hotel employee and now, with good reason, thinks of himself as a writer."

—Janet Maslin, New York Times

"For those of us who'd rather live in good hotels than in our own homes, oh Lordy, is this ever a horrifyingly good time. It's the sort of equivalent of WebMD for hypochondriacs: You know you're learning way more than is good for you, but you just can't stop reading. Tomsky, who may be an even better writer than a hotelier (and he's a damn good hotelier) has worked every job and every shift; he takes us into the bowels (sometimes literally) of the hotel business, with all the pomp and circumstance, the hidden filth, and the fears and aspirations and secrets of guests and staff alike."—Judith Newman, People (4 Stars)

"For the uninitiated, staying at a luxury hotel can be a little intimidating.... [But] front desk raconteur Jacob Tomsky is here to help. His sharp-witted, candid new book, Heads in Beds, demystifies the world of high-end hospitality.... Coarse, smart and wickedly funny, the author delivers hilarious caricatures of the hotel guests and colleagues he has encountered over the years.... Tightly written and laced with delicious insider tips."—John Wilwol, Washington Post

"A wonderfully indiscreet veteran of the hospitality industry, Jacob Tomsky knows his way around a hotel."—PARADE

"Room upgrades. Free movies. Late checkouts. Jacob Tomsky promises readers the keys to the hotel industry kingdom in his tell-all book, Heads in Beds. The one-time philosophy major has spent more than a decade working in the industry and, like room service, he delivers the goods.... Beyond tips, Tomsky has packed his book with outrageous anecdotes about guests...[and] the hotel staff too.... Tomsky has only worked at hotels in New Orleans and New York, so readers may wonder if his tips will work anywhere else. Maybe they will, maybe they won’t. But his stories are so good, it almost doesn’t matter."—Jessica Gresko, Associated Press

“Jacob Tomsky is a star. The kid writes like a dream. Heads in Beds is hilarious, literate, canny, indignant and kind—revealing an author who manages somehow to be both a total hustler and a complete humanitarian. I love this book. Keep an eye on this writer. I’m telling you, he’s a star.”

—Elizabeth Gilbert, author of Eat, Pray, Love: One Woman's Search for Everything Across Italy, India and Indonesia

“And I thought I had it bad when I worked in restaurants! Heads in Beds is a hilarious, informative, and naughty peek at what really happens behind the glitz and glamour of the hotel experience. Not content with dispensing advice on how to get a better room or avoiding the vengeful wrath of bellhops, maids, doormen, and front-desk clerks, Tomsky also spins a touching yarn on how he kept his dignity and humanity intact while dealing with insufferable guests, Expedia wannabes, predatory hotel managers, conniving coworkers, and the occasional pervert. After reading this book, you’ll become either a better-educated hotel guest who constantly receives great service—or realize why you always get that noisy room by the elevator shaft. As a survivor of America’s dysfunctional hospitality industry, I highly recommend this book.”

—Steve Dublanica, author of the New York Times bestseller Waiter Rant

“In pulling the musty curtains back on the seedy hotel business, Heads in Beds provides first-rate insights for all grades of travelers. But the real revelation here is Jacob Tomsky, whose writing combines presidential suite talent with rack-rate, smoking-room, vending-machine-down-the-hall edge.”

—Chuck Thompson, author of Smile When You’re Lying: Confessions of a Rogue Travel Writer

"Readable and often engaging.... [W]hen the author is passionate about his career and is able to express his passion on the page, it can be a joy to read... hilarious."—Kirkus Reviews

"Comparisons to Anthony Bourdain’s Kitchen Confidential (2000) are inevitable…. [B]oth Tomsky and Bourdain purport to expose the underbelly of service industries with which most readers are familiar, hotels and restaurants. But where Bourdain is all rock ’n’ roll, egotistical bluster, Tomsky is surprisingly earnest and sympathetic; there are, after all, no television programs called Top Desk Clerk. He wants your respect, not your adulation…. Indeed, it would be easy to pen a book about crazy hotel guests. But this memoir succeeds, instead, in humanizing the people who park our cars, clean our hotel rooms, and carry our luggage. You will never not tip housekeeping or your bellhop again. Tomsky fell into hotel work and proved to be rather good at it; the same can be said for his writing."—Booklist

"Those who want a hotel up-grade, who must make a same-day room cancellation without getting charged, or wonder why hotel water sometimes tastes like lemon Pledge need look no further than Tomsky's memoir, a collection of stories, memories, and secrets about the hospitality business. Bouncing around various hotel jobs...for more than 10 years, he's got the skinny that would make most travel sites blush.... But this is more than a collection of trade secrets; it's a colorful tale filled with vibrant characters from crazy bellmen to even crazier guests. Tomsky is a solid storyteller who is able to intricately detail all the insanity surrounding him."—Publishers Weekly

"With incredibly witty, from-the-gut prose, Mr. Tomsky provides an inside scoop on the good, the bad, and the incredibly ugly happenings that go on behind closed hotel doors—as well as front desk antics that happen right before your untrained, naïve eyes.... A very fun, entertaining read. It is incredibly relatable, not only for a consumer, but also for anyone who has worked in a public-oriented service industry. Despite his brash language, or perhaps in spite of it, the author comes across as sincere and personable with the patience of a saint—or at least he’s really good at faking it. Though it seems he was very good at this job, it’s about time for Jacob Tomsky to move on to bigger and better things. If this book is any indication, writing will be his next calling."—Renee C. Fountain, New York Journal of Books

"Tomsky shines in...this funny and profane memoir."—Nathan Gelgud, Biographile

"After the party, it’s the hotel lobby…. and that’s where things get real. Jacob Tomsky’s hilariously irreverent memoir Heads in Beds chronicles the all-work, no-sleep, but never dull lifestyle of the young hotelier and the innermost workings of high-end hotels...[and] shares five-star advice for your next check-in."—Gina Angelotti, Metro

"Heads in Beds is at turns hilarious, sad, too revealing, naughty, frightening and wildly fun. Tomsky proves to be a smart writer. His voice is warm and accessible, but he's also pleasantly snarky and potty-mouthed. He lets the reader see him at his smarmy, smooth-operating best and his filthy, fed-up worst. (And the book includes lots of tips, like how to eat and drink everything in your minibar for free, how to get extra amenities, and all of the things a hotel guest should never say to a front desk agent.)"—Alli Marshall, Mountain Xpress