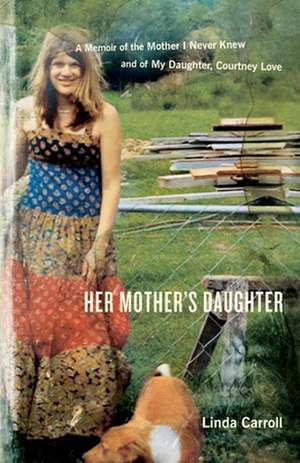

Her Mother's Daughter: A Memoir of the Mother I Never Knew and of My Daughter, Courtney Love

Autor Linda Carrollen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2006

As an adopted child, Linda Carroll created a magical world of her own, made up of dramatic adventures and the abiding fantasy that her real mother would come and take her away. When she finds herself pregnant at the age of eighteen, she is determined to have the perfect understanding with her child that she lacked with her adoptive mother. But readers will know better, for that baby grows up to be Courtney Love, desperately attention-seeking, deeply troubled, and one of the most talented women in rock.

Even as a baby, Courtney is beset by mood swings that no doctor can explain or cure. Her dark moods and paranoia escalate as she grows up, driving mother and daughter apart. When Courtney has a daughter of her own, Linda finally decides to find her own biological mother, and end the estrangement of generations of first-born daughters.

Her Mother’s Daughter is Linda Carroll’s story of self-discovery as an adopted daughter, a childlike hippie mother, and a woman determined to find herself before finding her roots. Set apart from the typical celebrity memoir by Carroll’s gifted storytelling, Her Mother’s Daughter gives a fresh perspective on the elusive yet enduring connections between mothers and daughters, and reveals the true history of the wildly confabulatory Courtney Love.

Preț: 114.69 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 172

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.95€ • 23.85$ • 18.45£

21.95€ • 23.85$ • 18.45£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 31 martie-14 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780767917889

ISBN-10: 076791788X

Pagini: 328

Ilustrații: PHOTO INSERT

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.41 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

ISBN-10: 076791788X

Pagini: 328

Ilustrații: PHOTO INSERT

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.41 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

Notă biografică

LINDA CARROLL was adopted at birth, raised in San Francisco, and only later discovered that her biological mother is the writer Paula Fox. Married at eighteen, and twice more before she was thirty, she is now the mother of five grown children, including singer/songwriter Courtney Love. She is a therapist and writer and lives in Corvallis, Oregon, with her husband of seventeen years.

Extras

CHAPTER 1

"This is your daughter." Her raspy voice on the telephone turns an ordinary statement into an accusation.

"Hello, Courtney," I say, bracing myself. I can't remember the last phone call that didn't end with screams and tears on her end and stony responses on mine. It has been years since we spoke with ease.

"I thought you'd like to know--I'm three months pregnant."

I hear my own sharp intake of breath and feel the sudden rush of emotions: fear, joy, dread, shock. I search for the next thing to say, the right thing; everything I think of seems hollow. It would be absurd if it weren't so painful. For the first time I am going to be a grandmother--yet I cannot even utter a sigh that isn't filtered through the screen of my own caution.

"That's very exciting news, Courtney," I manage.

"Guess what else, Mother? I just married a prince. He's the biggest rock star in the world."

Then I register the shock: she got married, and I hadn't been informed. Now she is going to have a child.

Things didn't start out this way, so guarded, so wary.

Courtney was my first child, born July 9, 1964, in the middle of the afternoon. I heard her cries, soft, then louder, and I reached for her. Nothing prepared me for that moment. Receiving her into my arms, I knew she was a miracle, a mystery entering the world. I couldn't believe this perfect baby had come from my body.

Until that moment, babies had held little interest for me. Yet from the instant I held Courtney, I felt that I was born to be a mother. In those first weeks, I inhaled her scent deeply--she smelled like wildness, wrapped in wind-dried sheets with a hint of Breck baby shampoo in her hair.

Get that baby on a schedule, Dr. Spock advised. But I knew what was right for her; I could feel it in my bones. Instinctively, I matched my timetable to hers, sleeping and waking when she did. She was so smart: she crawled and walked months before the baby charts said she would. At one year, she was using short sentences. People marveled at how articulate she was.

My concern was what happened when she became upset. At times she cried so hard, it was impossible to comfort her.

"Don't worry," the pediatrician said. "It's colic."

Deep down, though, I did worry. Something was hurting her that she wasn't able to express in words. As Courtney grew into a toddler, anticipating her moods became my central preoccupation. If I got to her crib as she awoke, all was well. But if I waited a moment too long, there was no consoling her. She could cry for hours.

Pale in complexion, Courtney had soft, generous features. Most startling were her sea green eyes, which shifted from tears to delight with breathtaking speed. Her radiance and enthusiasm were as extraordinary as her distress. As a two-year-old, she was always ready to climb into our Volkswagen Beetle and go for an adventure. She sat in the backseat as I drove, her pigtails bouncing between the two front seats as she asked her wide-eyed question, "Any news?"

She loved news.

But more than news, she loved music. Whenever the Beatles' hit "Michelle" came on the car radio, she would sing along. Already her voice held the dreamy inflection that would later become part of her fame.

Courtney was my first real love. I believed nothing could come between us.

Now here we are, twenty-five years later, holding a telephone conversation about a momentous event with such estrangement that I monitor even my sighs.

The life Courtney lives stuns and frightens me. Yet in her latest news, this pregnancy, I sense something hopeful.

"It's wonderful," I say. The words sound empty, concealing the emotions washing over me.

"Yeah, well, I thought you'd want to know," she says. The phone clicks, and she's gone.

I hold the receiver a moment longer before I drop it into its cradle.

I hear my husband, Tim. He is downstairs, pulling a roasted chicken out of the oven. He calls up to me: "Dinner."

We are leaving for Hawaii tomorrow to visit close friends. Our suitcases are packed and waiting by the front door.

"I'll be right there," I call back.

I sit down on the bed. I can't bear to talk to anyone just yet, not even Tim. Our cat, Nelson, sidles over and nudges my arm. I set him on my lap. A current of excitement mixed with dread courses through me. My heart races even faster than my thoughts. Finally, I go downstairs.

I tell Tim the news.

"Why do you call the baby 'she'?" he asks.

"I don't know," I say, preoccupied. "I'm just certain the baby will be a girl."

Something is stirring inside, a feeling on the periphery of my awareness whose arrival I've been expecting for years. It's as though I have stepped into a deep stream and am being carried somewhere new.

Two days later at Puako beach on the big island of Hawaii, I sit on the edge of a lava formation that juts out into the Pacific. I have left a gathering of friends; I feel a need to be alone. Tall palms, with their lush foliage, shade the porous rock around me. I look for that mysterious green flash that sometimes lights up the sky as the sun sinks beneath the horizon.

The water is calm. Below me I see schools of fish--yellow butterfly fish, parrot fish. A pod of spinner dolphins, called the Nai'a, play off the shore.

Old ones, young ones, babies. Generations.

Generations.

In my mind's eye, the word flashes. Then, with absolute clarity, I know it is time to find my mother, the woman who gave birth to me.

When I was growing up, people asked me how I felt about being adopted, and I always said, "It's not an issue." I believed my own lie. The longing ran too deep to acknowledge: for a family who looked like me, for a genealogy, for the full story of my life. Even deeper lay the fear of what I would discover. Now, with the news of Courtney's pregnancy, the desire to find my birth mother, to unravel the mystery of my own origin, was too strong to ignore.

CHAPTER 2

As a child, I often asked to hear the story of how I became the adopted daughter of Louella and Jack Risi. They never tired of describing the ride home from the hospital when I was just ten days old, in April 1944, laughing at the memory of my bald head. I listened for something else: clues about the unknown woman who had given birth to me before I became "Louella's child."

Before I fell asleep each night, I fantasized about my birth mother. She was a queen, I imagined, searching for her lost five-year-old princess.

Each morning, I sat at the curb outside our house, studying the stream of pedestrians on their way to the streetcar, hoping to see her. The Drunk Lady passed first, as she shuffled toward the corner bar. Though she never glanced my way, I gaped at her ruddy face, with its uneven makeup and bulbous nose, fearing she was The One.

Ginger came later. Glamorous as a movie star, she wore sparkly silver pins on her lapels, and her upswept hairdo ended in a dramatic swirl. She always had a special smile for me as she strode by in her rhinestone-studded shoes. One day she stopped and looked right into my eyes.

"How are you this morning, honey?" she asked.

In my excitement, I could muster only a "fine."

She continued on, but her warmth convinced me she was The One. She would stop again, I imagined, and this time she would say, "Okay, sweetheart, you can come home with me."

I hurried off to share my excitement with my friend Helen. "Ginger is my real mother," I explained, "and soon she'll take me with her." Helen told her mother, who told another mother, and before long, Louella heard the news. When I went in for lunch, I could tell she was angry by the pinch in her meticulously plucked eyebrows. She led me into the living room, where she stood rubbing her hands on a starched white apron.

"Young lady," she said, taking a deep breath to compose herself. "The woman who had you was too irresponsible to care for you. You are a fortunate little girl to have people who wanted you." Tears welled in her eyes.

My face flushed as she left the room. I had never seen her cry before, and I felt ashamed for causing trouble. At once, I grasped what she meant by my good fortune. Not only was Ginger not my real mother, but, just as I had feared, my real mother was someone like the Drunk Lady, or even worse.

After that, I stopped searching the faces of beautiful women for signs that one might be her. I pushed my longing deep inside, and tried to think of Jack and Louella as my "real parents." But it never felt right: I avoided calling them Mom and Dad. Though I referred to them as "my mother" and "my father" to others, they were always Jack and Louella to me.

We lived in a beige two-story stucco house in Ewing Terrace, a quiet cul-de-sac near Lone Mountain in San Francisco. On the mountain's slope lay the ruins of one of the city's first cemeteries, veined with trails leading up toward the summit. In the late 1940s, those paths were the stomping grounds of derelicts and hobos, and my friend Helen warned me that the ghost of a child-murdering gold miner roamed them as well. Helen's story made me curious, and one morning when I was five, I set off for Lone Mountain, zigzagging across lawns to evade the sharp eyes of the neighborhood women who gossiped with Louella. I made it to the mountain and began to climb. In my thin sundress and sandals, I scraped my bare legs against brambles, but kept ascending until my eye caught a flicker of flames through the brush. Intrigued, I clambered off the path. As I drew closer, I saw a bearlike man poking a small fire. The ground around him was cluttered with liquor bottles. Seeing me, he turned and bellowed, "What do you want?"

I froze.

He jumped up and grabbed me. The smell he gave off was foul, like our cat's litter box. He began to grope me roughly, sticking his huge hands under my dress. Terrified, I wet my pants. He released me with disgust.

With more speed than I knew I possessed, I ran home. Only when my badly scuffed shoes touched the sidewalk in front of my house did I stop. I sat in my spot on the curb until my trembling body grew calm.

When I went inside, Louella was waiting. She took one look at my appearance and shut off the vacuum cleaner. "You've ripped your dress," she cried. "Oh, look at you. You just can't keep clean. Go take a bath this instant."

Upstairs, I hid my wet underpants in an old shoebox and drew water for a bath. Louella joined me, adjusted the temperature, and sat down on the toilet seat. "I didn't mean to scare you," she said. Her irritation had ebbed, and she eyed the scrapes on my legs sympathetically. "Those look like they hurt! Have you been climbing trees again?" As she spoke, she lightly scratched my back with her long, red nails. I loved it when she did that. Her hands soothed me. "Whatever did you do to tear your dress?" she asked.

"I fell down," I answered meekly.

"Sometimes I get so angry at what a tomboy you are," she said. "I was never like that, not one day in my life." Then she added, as if to reassure herself, "Everyone says you'll grow out of it."

The bathwater and Louella's calming hands made the ghost miner seem far away. I relaxed even more, sensing that my reputation as a tomboy would spare me further questions about the mess made of my best dress--yellow with red cherries on it--that I wore to Mass on Sunday mornings.

Later that night, I thought about how close I had come to ending up like the child Helen had told me about, stuffed in a jar, my body cut into little pieces like the dill pickles I loved to eat. I studied my picture of Mother Mary, wearing her soft blue and white robes, surrounded by golden-haired angels. In a whisper, I promised her I would stay close to home if she would protect me. The next morning, I snuck my soiled underpants into the garbage can and figured my secret was safe.

My sundress with the cherry print was not easily mended.

"You'll have to wear your blue one," Louella told me when Sunday came.

I was glad. I never wanted to see the cherry dress again. I settled into the passenger seat of our white Oldsmobile, and we drove to the Catholic chapel of the Women's College at the top of Lone Mountain. As the car climbed, so did a woman and a little girl about my age. We passed them every week, making their way up the steep sidewalk to the church. This particular morning, a light rain was falling when we noticed them trudging along without an umbrella. Louella stopped the car and rolled down the window.

"Would you like a ride?" she asked.

I was surprised. We had passed them so many times before. Gratefully, they joined us, and we drove on in silence.

After we dropped them off at the front of the church, I offered Louella shy praise: "You're really nice."

"Anyone would help a neighbor," she replied mechanically. A moment later, she added, "Believe me, I know about being poor."

During Mass, I glanced up at Louella several times, seeking a sign to explain her sudden, generous impulse, but found none. So much of what she did was a mystery, even though we spent most of our time together. She was like a familiar stranger whose actions I could never quite understand.

A few weeks later, there was a knock at our front door. Opening it, I saw a short, fair-haired woman wearing a blue wool suit.

"You must be the little girl I've come for," she said kindly, stepping into the hall. I stared, wondering who she might be. The woman set down her large suitcase.

"Well, you're as pretty as your picture," she said. "We're going to get along fine."

I doubted it. I ran up to my room and shut the door.

Before long, Louella followed. "Linda, what on earth is wrong?" she asked. "Why are you behaving so rudely?"

From the Hardcover edition.

"This is your daughter." Her raspy voice on the telephone turns an ordinary statement into an accusation.

"Hello, Courtney," I say, bracing myself. I can't remember the last phone call that didn't end with screams and tears on her end and stony responses on mine. It has been years since we spoke with ease.

"I thought you'd like to know--I'm three months pregnant."

I hear my own sharp intake of breath and feel the sudden rush of emotions: fear, joy, dread, shock. I search for the next thing to say, the right thing; everything I think of seems hollow. It would be absurd if it weren't so painful. For the first time I am going to be a grandmother--yet I cannot even utter a sigh that isn't filtered through the screen of my own caution.

"That's very exciting news, Courtney," I manage.

"Guess what else, Mother? I just married a prince. He's the biggest rock star in the world."

Then I register the shock: she got married, and I hadn't been informed. Now she is going to have a child.

Things didn't start out this way, so guarded, so wary.

Courtney was my first child, born July 9, 1964, in the middle of the afternoon. I heard her cries, soft, then louder, and I reached for her. Nothing prepared me for that moment. Receiving her into my arms, I knew she was a miracle, a mystery entering the world. I couldn't believe this perfect baby had come from my body.

Until that moment, babies had held little interest for me. Yet from the instant I held Courtney, I felt that I was born to be a mother. In those first weeks, I inhaled her scent deeply--she smelled like wildness, wrapped in wind-dried sheets with a hint of Breck baby shampoo in her hair.

Get that baby on a schedule, Dr. Spock advised. But I knew what was right for her; I could feel it in my bones. Instinctively, I matched my timetable to hers, sleeping and waking when she did. She was so smart: she crawled and walked months before the baby charts said she would. At one year, she was using short sentences. People marveled at how articulate she was.

My concern was what happened when she became upset. At times she cried so hard, it was impossible to comfort her.

"Don't worry," the pediatrician said. "It's colic."

Deep down, though, I did worry. Something was hurting her that she wasn't able to express in words. As Courtney grew into a toddler, anticipating her moods became my central preoccupation. If I got to her crib as she awoke, all was well. But if I waited a moment too long, there was no consoling her. She could cry for hours.

Pale in complexion, Courtney had soft, generous features. Most startling were her sea green eyes, which shifted from tears to delight with breathtaking speed. Her radiance and enthusiasm were as extraordinary as her distress. As a two-year-old, she was always ready to climb into our Volkswagen Beetle and go for an adventure. She sat in the backseat as I drove, her pigtails bouncing between the two front seats as she asked her wide-eyed question, "Any news?"

She loved news.

But more than news, she loved music. Whenever the Beatles' hit "Michelle" came on the car radio, she would sing along. Already her voice held the dreamy inflection that would later become part of her fame.

Courtney was my first real love. I believed nothing could come between us.

Now here we are, twenty-five years later, holding a telephone conversation about a momentous event with such estrangement that I monitor even my sighs.

The life Courtney lives stuns and frightens me. Yet in her latest news, this pregnancy, I sense something hopeful.

"It's wonderful," I say. The words sound empty, concealing the emotions washing over me.

"Yeah, well, I thought you'd want to know," she says. The phone clicks, and she's gone.

I hold the receiver a moment longer before I drop it into its cradle.

I hear my husband, Tim. He is downstairs, pulling a roasted chicken out of the oven. He calls up to me: "Dinner."

We are leaving for Hawaii tomorrow to visit close friends. Our suitcases are packed and waiting by the front door.

"I'll be right there," I call back.

I sit down on the bed. I can't bear to talk to anyone just yet, not even Tim. Our cat, Nelson, sidles over and nudges my arm. I set him on my lap. A current of excitement mixed with dread courses through me. My heart races even faster than my thoughts. Finally, I go downstairs.

I tell Tim the news.

"Why do you call the baby 'she'?" he asks.

"I don't know," I say, preoccupied. "I'm just certain the baby will be a girl."

Something is stirring inside, a feeling on the periphery of my awareness whose arrival I've been expecting for years. It's as though I have stepped into a deep stream and am being carried somewhere new.

Two days later at Puako beach on the big island of Hawaii, I sit on the edge of a lava formation that juts out into the Pacific. I have left a gathering of friends; I feel a need to be alone. Tall palms, with their lush foliage, shade the porous rock around me. I look for that mysterious green flash that sometimes lights up the sky as the sun sinks beneath the horizon.

The water is calm. Below me I see schools of fish--yellow butterfly fish, parrot fish. A pod of spinner dolphins, called the Nai'a, play off the shore.

Old ones, young ones, babies. Generations.

Generations.

In my mind's eye, the word flashes. Then, with absolute clarity, I know it is time to find my mother, the woman who gave birth to me.

When I was growing up, people asked me how I felt about being adopted, and I always said, "It's not an issue." I believed my own lie. The longing ran too deep to acknowledge: for a family who looked like me, for a genealogy, for the full story of my life. Even deeper lay the fear of what I would discover. Now, with the news of Courtney's pregnancy, the desire to find my birth mother, to unravel the mystery of my own origin, was too strong to ignore.

CHAPTER 2

As a child, I often asked to hear the story of how I became the adopted daughter of Louella and Jack Risi. They never tired of describing the ride home from the hospital when I was just ten days old, in April 1944, laughing at the memory of my bald head. I listened for something else: clues about the unknown woman who had given birth to me before I became "Louella's child."

Before I fell asleep each night, I fantasized about my birth mother. She was a queen, I imagined, searching for her lost five-year-old princess.

Each morning, I sat at the curb outside our house, studying the stream of pedestrians on their way to the streetcar, hoping to see her. The Drunk Lady passed first, as she shuffled toward the corner bar. Though she never glanced my way, I gaped at her ruddy face, with its uneven makeup and bulbous nose, fearing she was The One.

Ginger came later. Glamorous as a movie star, she wore sparkly silver pins on her lapels, and her upswept hairdo ended in a dramatic swirl. She always had a special smile for me as she strode by in her rhinestone-studded shoes. One day she stopped and looked right into my eyes.

"How are you this morning, honey?" she asked.

In my excitement, I could muster only a "fine."

She continued on, but her warmth convinced me she was The One. She would stop again, I imagined, and this time she would say, "Okay, sweetheart, you can come home with me."

I hurried off to share my excitement with my friend Helen. "Ginger is my real mother," I explained, "and soon she'll take me with her." Helen told her mother, who told another mother, and before long, Louella heard the news. When I went in for lunch, I could tell she was angry by the pinch in her meticulously plucked eyebrows. She led me into the living room, where she stood rubbing her hands on a starched white apron.

"Young lady," she said, taking a deep breath to compose herself. "The woman who had you was too irresponsible to care for you. You are a fortunate little girl to have people who wanted you." Tears welled in her eyes.

My face flushed as she left the room. I had never seen her cry before, and I felt ashamed for causing trouble. At once, I grasped what she meant by my good fortune. Not only was Ginger not my real mother, but, just as I had feared, my real mother was someone like the Drunk Lady, or even worse.

After that, I stopped searching the faces of beautiful women for signs that one might be her. I pushed my longing deep inside, and tried to think of Jack and Louella as my "real parents." But it never felt right: I avoided calling them Mom and Dad. Though I referred to them as "my mother" and "my father" to others, they were always Jack and Louella to me.

We lived in a beige two-story stucco house in Ewing Terrace, a quiet cul-de-sac near Lone Mountain in San Francisco. On the mountain's slope lay the ruins of one of the city's first cemeteries, veined with trails leading up toward the summit. In the late 1940s, those paths were the stomping grounds of derelicts and hobos, and my friend Helen warned me that the ghost of a child-murdering gold miner roamed them as well. Helen's story made me curious, and one morning when I was five, I set off for Lone Mountain, zigzagging across lawns to evade the sharp eyes of the neighborhood women who gossiped with Louella. I made it to the mountain and began to climb. In my thin sundress and sandals, I scraped my bare legs against brambles, but kept ascending until my eye caught a flicker of flames through the brush. Intrigued, I clambered off the path. As I drew closer, I saw a bearlike man poking a small fire. The ground around him was cluttered with liquor bottles. Seeing me, he turned and bellowed, "What do you want?"

I froze.

He jumped up and grabbed me. The smell he gave off was foul, like our cat's litter box. He began to grope me roughly, sticking his huge hands under my dress. Terrified, I wet my pants. He released me with disgust.

With more speed than I knew I possessed, I ran home. Only when my badly scuffed shoes touched the sidewalk in front of my house did I stop. I sat in my spot on the curb until my trembling body grew calm.

When I went inside, Louella was waiting. She took one look at my appearance and shut off the vacuum cleaner. "You've ripped your dress," she cried. "Oh, look at you. You just can't keep clean. Go take a bath this instant."

Upstairs, I hid my wet underpants in an old shoebox and drew water for a bath. Louella joined me, adjusted the temperature, and sat down on the toilet seat. "I didn't mean to scare you," she said. Her irritation had ebbed, and she eyed the scrapes on my legs sympathetically. "Those look like they hurt! Have you been climbing trees again?" As she spoke, she lightly scratched my back with her long, red nails. I loved it when she did that. Her hands soothed me. "Whatever did you do to tear your dress?" she asked.

"I fell down," I answered meekly.

"Sometimes I get so angry at what a tomboy you are," she said. "I was never like that, not one day in my life." Then she added, as if to reassure herself, "Everyone says you'll grow out of it."

The bathwater and Louella's calming hands made the ghost miner seem far away. I relaxed even more, sensing that my reputation as a tomboy would spare me further questions about the mess made of my best dress--yellow with red cherries on it--that I wore to Mass on Sunday mornings.

Later that night, I thought about how close I had come to ending up like the child Helen had told me about, stuffed in a jar, my body cut into little pieces like the dill pickles I loved to eat. I studied my picture of Mother Mary, wearing her soft blue and white robes, surrounded by golden-haired angels. In a whisper, I promised her I would stay close to home if she would protect me. The next morning, I snuck my soiled underpants into the garbage can and figured my secret was safe.

My sundress with the cherry print was not easily mended.

"You'll have to wear your blue one," Louella told me when Sunday came.

I was glad. I never wanted to see the cherry dress again. I settled into the passenger seat of our white Oldsmobile, and we drove to the Catholic chapel of the Women's College at the top of Lone Mountain. As the car climbed, so did a woman and a little girl about my age. We passed them every week, making their way up the steep sidewalk to the church. This particular morning, a light rain was falling when we noticed them trudging along without an umbrella. Louella stopped the car and rolled down the window.

"Would you like a ride?" she asked.

I was surprised. We had passed them so many times before. Gratefully, they joined us, and we drove on in silence.

After we dropped them off at the front of the church, I offered Louella shy praise: "You're really nice."

"Anyone would help a neighbor," she replied mechanically. A moment later, she added, "Believe me, I know about being poor."

During Mass, I glanced up at Louella several times, seeking a sign to explain her sudden, generous impulse, but found none. So much of what she did was a mystery, even though we spent most of our time together. She was like a familiar stranger whose actions I could never quite understand.

A few weeks later, there was a knock at our front door. Opening it, I saw a short, fair-haired woman wearing a blue wool suit.

"You must be the little girl I've come for," she said kindly, stepping into the hall. I stared, wondering who she might be. The woman set down her large suitcase.

"Well, you're as pretty as your picture," she said. "We're going to get along fine."

I doubted it. I ran up to my room and shut the door.

Before long, Louella followed. "Linda, what on earth is wrong?" she asked. "Why are you behaving so rudely?"

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

Advance Praise for Her Mother’s Daughter

“There is a delicious fictional quality to this true-life story that I found riveting. In Carroll’s deft telling, the book is a kind of resurrection of a family . . . I think I loved Her Mother's Daughter most for the devotion that Linda Carroll has for her unusual family through decades of separations and unconventional journeys.”

—Terry Ryan, author of The Prize Winner of Defiance, Ohio

“Looking backward and forward in time, this haunting memoir tells the story of a young woman’s journey to finding herself, her birth mother, and her daughter, Courtney Love. The candor and power of these pages illuminates the difficulties of all mother-daughter relationships, but offers a rare glimpse into that elemental relationship when it is shadowed by the temperamental features of early-onset bipolar disorder. Linda Carroll has grit and grace, and writes like her mother’s daughter.”

—Demitri F. Papolos, M.D., and Janice Papolos, authors of The Bipolar Child

“There is a delicious fictional quality to this true-life story that I found riveting. In Carroll’s deft telling, the book is a kind of resurrection of a family . . . I think I loved Her Mother's Daughter most for the devotion that Linda Carroll has for her unusual family through decades of separations and unconventional journeys.”

—Terry Ryan, author of The Prize Winner of Defiance, Ohio

“Looking backward and forward in time, this haunting memoir tells the story of a young woman’s journey to finding herself, her birth mother, and her daughter, Courtney Love. The candor and power of these pages illuminates the difficulties of all mother-daughter relationships, but offers a rare glimpse into that elemental relationship when it is shadowed by the temperamental features of early-onset bipolar disorder. Linda Carroll has grit and grace, and writes like her mother’s daughter.”

—Demitri F. Papolos, M.D., and Janice Papolos, authors of The Bipolar Child

Descriere

Given up for adoption at birth, the author is determined to have a perfect understanding with her own child that she never had with her adoptive mother. However, that baby grows up to be Courtney Love. When Courtney has a daughter of her own, the author decides to find her own biological mother and end the estrangement of mothers and daughters.