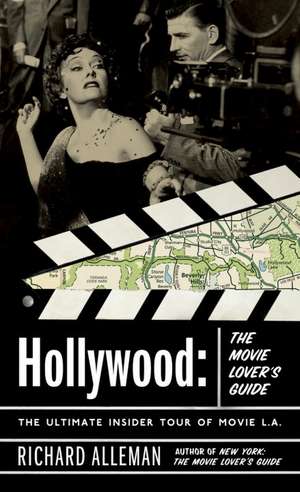

Hollywood: The Ultimate Insider Tour of Movie L.A.

Autor Richard Allemanen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 ian 2005

Film & TV locations: the Hollywood Hills house where Barbara Stanwyck seduced Fred MacMurray in Double Indemnity...the funky apartment building where William Holden lived in Sunset Boulevard...the exotic Frank Lloyd Wright mansion that's housed everyone from Harrison Ford in Blade Runner to David Boreanaz on TV's Buffy the Vampire Slayer....the landmark Art Deco former department store that has doubled for a glamorous hotel in Topper (1936) and an elegant nightclub in The Aviator (2004)... the Halloween and Nightmare on Elm Street houses... the Seinfeld and Alias apartment buildings... the Six Feet Under funeral home...The Brady Bunch and Happy Days houses...the Charlie's Angels office...the real Melrose Place...and many more

VIP tours: from legendary studios like Warner Bros., MGM (now Sony Pictures), and Universal to movie-star homes like Barbra Streisand's former Malibu compound…

Crime scenes and scandal spots: the driveway where Sal Mineo was murdered, the Nicole Brown Simpson condo, the Sharon Tate estate, Marilyn Monroe's last address, the Beverly Hills Mansion where Bugsy Siegal was rubbed out…the Hollywood hotel where Janice Joplin O.D.’d…

Plus: Remarkable new museums...Superstar cemeteries...Historic hotels...Hip clubs and restaurants....Fabulous restored movie palaces… Spectacular movie star mansions and château apartments…

Taking movie lovers behind the gates of the exclusive, often hidden world of Tinsel Town, Hollywood: The Movie Lover's Guide is the ultimate insider's guide to L.A.'s reel attractions.

Preț: 143.07 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 215

Preț estimativ în valută:

27.39€ • 29.76$ • 23.02£

27.39€ • 29.76$ • 23.02£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 31 martie-14 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780767916356

ISBN-10: 0767916352

Pagini: 512

Ilustrații: OVER 250 B&W PHOTOS THROUGHOUT

Dimensiuni: 124 x 203 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.48 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0767916352

Pagini: 512

Ilustrații: OVER 250 B&W PHOTOS THROUGHOUT

Dimensiuni: 124 x 203 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.48 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

Notă biografică

RICHARD ALLEMAN, a longtime contributing editor at Travel + Leisure magazine, is a former travel editor of Vogue, where he is still a frequent contributor on travel and entertainment. Currently living in New York City, he has carried on a love affair with Los Angeles, where he lived for several years as an actor and writer.

Extras

Hollywood: Birth of a Boulevard

Hollywood Boulevard—from Vista to Vine

In the 1880s, there were ranches, bean fields, orange and lemon groves. It was a peaceful, pastoral place—a far cry from the big city called Los Angeles that was growing up just five miles to the southeast. Staunchly conservative, early Hollywood was populated mostly with transplanted Midwesterners. One of these, a prohibitionist from Kansas named Harvey Wilcox, had some 120 acres that his wife had christened “Hollywood” because, so the story goes, she had met a woman on a train who had spoken in glowing terms of her summer home back East called Hollywood. When the Wilcoxes subdivided their property in 1887, the name that Mrs. Wilcox had so fancied was printed on the map advertising the lots the couple was selling for $150 an acre. Hollywood—like so many communities in Southern California—was officially launched as a real estate development.

The little community grew steadily, if not dramatically. By 1897, Hollywood had its own post office, and in 1903, the citizens (the population was now close to 700) voted to be incorporated as a city. One of the first things that the officials of this new little “sixth-class” city did was to enact a number of ordinances. Ranging from limiting the hours that billiard and pool rooms could be open to banning the sale of alcoholic beverages, Hollywood’s laws reflected the essential conservatism of its citizens. When this same citizenry voted in 1910 to have Hollywood annexed by the city of Los Angeles, it wasn’t out of any particular fondness for their worldly metropolitan neighbor; it was simply because they needed L.A.’s water and sewer system.

Needless to say, when the first movie folk came to town in 1911, these Eastern outsiders of questionable moral character were not exactly welcomed with open arms by Hollywood’s straitlaced locals. Indeed, in many ways, this Midwestern town that happened to be in Southern California was, except for the weather, an unlikely candidate to become the movie capital of the world.

Ironically, it was Hollywood’s conservatism that was indirectly responsible for its first movie studio. For when the Centaur Film Co. of Bayonne, New Jersey, arrived in California in 1911, they found a perfect setup for moviemaking in a former Hollywood tavern that had fallen on hard times owing to the town’s tough liquor laws. Besides its main building, the tavern property offered a barn and corral that would facilitate the shooting of Westerns, a group of small outbuildings that could be used as dressing rooms, and a bungalow for additional office space. Within a matter of days, the company was turning out three films a week from what they called the Nestor studio.

Universal’s founder, Carl Laemmle, was next on the Hollywood scene. Arriving in 1912, Laemmle set up his first West Coast base of operations on the southwest corner of Gower and Sunset, just across the street from the Nestor studio. A year later, a trio made up of Cecil B. DeMille, Jesse Lasky, and Samuel Goldfish (later Goldwyn) also settled in Hollywood and shot the town’s first feature-length film, The Squaw Man, based in a barn at the corner of Vine and Selma. As more and more movie people came, the locals who had at first looked down on the film business suddenly found themselves either directly in its employ or involved in businesses—from rooming houses to restaurants—that were making money thanks to motion pictures. In a word, Hollywood was booming—and the little Midwestern town in Southern California would never be the same again. By 1920, Hollywood’s population had grown to 36,000. By the end of the twenties it would swell to over 150,000.

As Hollywood made the transition from village to metropolis, a great boulevard kept pace with the new city’s growth and came to be the center of its wealth, power, and glory. Edged with movie palaces, stately hotels, glamorous restaurants and apartment buildings, Hollywood Boulevard was, in its heyday, one of the most dazzling thoroughfares in the country. The glamour started to wane in the late 1950s, however, and by the time the 1980s had rolled around this once great main street had lost much of its luster and parts of it had become home to punks, prostitutes, and panhandlers. It was then that concerned citizens and the local business community started taking action, realizing that the Boulevard’s ultimate glory lay in its past. Although there were differing visions of how best to revive the area, everyone agreed that something had to be done. In some ways, too, Hollywood Boulevard was unique because, owing to its long period of decline in the sixties and seventies, many architecturally distinguished buildings and theaters had not been torn down, as they had been in more thriving areas of Los Angeles. In other words, Hollywood Boulevard was a remarkably intact, if somewhat down-at-heels, monument to the city that would always be considered the motion picture capital of the world.

Happily, the last decade has been one of revival, with many of the Boulevard’s historic buildings now either restored or slated for restoration. Some have been turned into museums, whereas others are back to their original uses as theaters, restaurants, cafes, and nightclubs. At the same time, Hollywood Boulevard has welcomed a couple of new large-scale projects such as the Kodak Theatre, built to host the Academy Awards ceremonies, and the Hollywood & Highland complex, an entertainment mall designed in the spirit of a famous Old Hollywood movie set.

All this is not to say that Hollywood Boulevard has been totally sanitized. The old souvenir shops, fast-food outlets, tattoo parlors, and T-shirt emporiums are still very much a part of the mix—and the street’s funky charm. But whereas twenty years ago, when this book was originally published, finding the history that lurked on the movie capital’s main street was not easy. Today, it’s visible everywhere. And since so much of this history is connected with the film industry and its larger-than-life personalities, Hollywood Boulevard is a logical first stop in the movie lover’s Los Angeles odyssey. Here, a look at Hollywood’s main street and its new splendor, plus trips to some fascinating places beyond the Boulevard—from the legendary barn where The Squaw Man was shot back in 1913 to a secret enclave of Mediterranean houses where silent films stars once lived. Welcome to Hollywood—as it is now . . . and as it was then.

For convenient sightseeing, this first chapter covers Hollywood Boulevard and the vicinity from Vista to Vine Street. The best way to tour the Boulevard proper is on foot. To reach some of the places mentioned on Franklin Avenue and in the hills behind the Boulevard, a car is suggested.

1. Grauman’s Chinese Theater

6925 Hollywood Boulevard

Built by Hollywood developer C. E. Toberman for theater magnate Sid Grauman in 1927, the Chinese is the most famous movie house in the world. Reason? No other picture palace has ever come up with a publicity stunt as clever or successful as Grauman’s hallowed ritual of having movie stars leave their footprints, handprints, and autographs in the cement of the theater’s forecourt.

There are all sorts of stories as to how the custom began. The one most widely told is that silent screen star Norma Talmadge stopped by to tour the construction site and accidently stepped into some wet cement as she was getting out of her car. Another version says Grauman got the idea from Mary Pickford, who told him how her dog Zorro had gotten into some wet cement at her driveway up at Pickfair. “Now, we’ll have Zorro with us forever,” Pickford reportedly said to Grauman. Two days later, Grauman invited Pickford, her husband, Douglas Fairbanks, and Norma Talmadge to come celebrate the construction of his new theater with their prints and signatures. As these proved too faint upon drying, Grauman invited the same three stars as well as a few reporters back for an “official” ceremony. It made good copy—and indeed it still does.

Since that time, some 240 celebs have cemented their fame in the forecourt of the Chinese. Not all of the celebs have left just hand- and footprints: silent film star Harold Lloyd’s trademark glasses have been immortalized in cement here—as have Sonja Henie’s ice skates, John Wayne’s fist, Harpo Marx’s harp, Jimmy Durante’s nose, and one of Betty Grable’s “million-dollar” gams. Besides real-live people, Edgar Bergen’s dummy Charlie McCarthy has signed in at the Chinese; Roy Rogers’s horse Trigger and Gene Autry’s Champion have left hoofprints; Star Wars robots R2D2 and C3PO have rolled over the cement into immortality; and in 1984 Donald Duck marked his fiftieth birthday at the Chinese with two giant webbed-foot prints.

While movie lovers might question the credibility of some of the “legends” represented in the forecourt of the Chinese, few star presences have ever been publicly protested. A notable exception was Ali MacGraw’s December 1972 appearance at the theater, which was met by a small band of chanting and placard-carrying demonstrators who felt Ms. MacGraw’s lackluster four-film (at the time) career did not merit the full concrete treatment. (So far, though, Ms. MacGraw’s prints are still in place and have not wound up in the basement of the theater—the fate, according to insiders, that a number of the prints of some lesser legends are said to have met.)

There is more to the mystique of the Chinese Theater than footprints. Throughout its history, the theater has been one of Hollywood’s premier premiere places—ever since Cecil B. DeMille’s King of Kings opened the Chinese on May 27, 1927. Besides premieres, the theater hosted the Academy Awards in 1944, 1945, and 1946. The Chinese is also a treasure of movie theater architecture and interior design—and happily, after a $7 million restoration in 2001 by Mann Theatres, which has owned the Chinese since 1973, this 1920s picture palace is almost as splendid as it once was. Outside, the theater’s façade is a wonderful fantasy of a Chinese temple—complete with huge stone guard dogs on either side of the entrance and a sky-soaring pagoda roof. Inside, the lavish lobby and auditorium have marvelous murals, columns, Oriental vases, furniture, and carpets. It’s the kind of theater they just don’t build anymore—and simply being here makes up for anything that might be up on the screen.

Visit www.mann theatres.com

2. Mann’s Chinese 6 Theaters

6801 Hollywood Boulevard

Opened by Mann Theatres in 2001 to coincide with the debut of the restored Chinese Theater next door, this upscale multiplex features a stylish minimalist version of its legendary sibling’s Chinese decor as well as twenty-first-century amenities such as stadium seating, digital THX sound, and VIP lounges.

3. Hollywood Entertainment Museum

7021 Hollywood Boulevard

There’s something for everyone in this vast (32,000 square feet) exhibition hall’s assemblage of movie and television props, costumes, sets, and hands-on exhibits. TV fans can check out the Cheers barroom, the Star Trek Starship Enterprise control room, and Agent Mulder’s X-Files office. Sci-fi nuts can ogle forty years’ worth of monsters and scale models—from a Gort robot from The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) to the alien spacecraft from Independence Day (1996). Among the interactive exhib-

its, the Foley Room has visitors adding sound effects to a film

sequence. In addition to its permanent displays, the museum

features excellent special shows such as “Marlene Dietrich:

Treasures from the Estate Collection”; “Smoke, Lies, and Vid-eotape,” which documented Hollywood’s role in glamorizing smoking; and “USO Presenting Hollywood Salutes the Troops,” focusing on legendary USO shows from World War II up to the war in Afghanistan.

For current museum hours and information on special exhibitions, call 323–465–7900 and visit www.hollywoodmuseum.com.

4. The Walk of Fame

If Grauman’s Chinese Theater could achieve world renown through its sidewalk—why not all of Hollywood? At least, that’s what a group of local business people thought in the late 1950s when they concocted a scheme to turn the sidewalks of a deteriorating Hollywood Boulevard into a vast star-studded terrazzo commemorating the legends of the film, radio, television, and recording industries. Shop and property owners along the proposed walkway were asked to contribute $85 per front foot and $1.25 million was raised to begin the project that initially immortalized 1,558 personalities and continues to do so at the rate of about fifteen to twenty stars a year. (There are now more than 2,200.)

In 1983, theater was added as a fifth Walk of Fame category and Mickey Rooney, then starring in Sugar Babies at Hollywood’s Pantages Theater, became the first “two-star” celebrity when he was given his second star for his recent theatrical success. To make the Walk of Fame, new stars must be sponsored—by their agents, their producers, their fan clubs, or a local business—for the honor. A special committee of the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce then votes on the candidate’s acceptability, taking into consideration professional as well as humanitarian achievements. If the candidate fulfills the requirements, the sponsor pays approximately $15,000 to cover the cost of the star, the ceremony that goes along with it, and the Walk’s ongoing maintenance and repairs.

The Walk of Fame extends for some two and a half miles from La Brea to Gower along both sides of Hollywood Boulevard and from Sunset to Yucca along Vine Street.

Dedication ceremonies for the Walk of Fame are usually held at noon on the third Thursday of each month. Check with the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce for exact times and locations by calling 323–469–8311.

5. Hollywood Gateway Sculpture

Hollywood Boulevard/La Brea Avenue

Erected in 1993 on the strategic corner of Hollywood Boulevard and La Brea Avenue—often considered the western “gateway” to downtown Hollywood—this striking installation by artists Catherine Hardwicke and Hari West pays politically correct homage to four screen goddesses, each from a different ethnic background. The women, their gigantic stainless-steel images holding up a 30-foot gazebo, are Mae West, Dorothy Dandridge, Anna May Wong, and Delores Del Rio. The whole concoction is topped by a tiny Marilyn Monroe weathervane.

6. Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel

7000 Hollywood Boulevard

A 1927 newspaper ad touted its grand opening as “the dominant social occasion of the year.” “Don’t wait,” it enthused. “You will see the greatest number of stage and screen stars ever assembled.” Among those invited were: Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, Norma Talmadge, Constance Talmadge, Pola Negri, Richard Barthelmess, John Gilbert, Harold Lloyd, Greta Garbo, Gloria Swanson, Rod La Rocque, Janet Gaynor, Will Rogers, Clara Bow, Sid Chaplin, Sid Grauman, Wallace Beery, Charles Chaplin . . . and scores of others. And most of them came—not only because, at twelve stories and four hundred rooms, this was the most impressive hotel ever to be built in Hollywood, but also because the syndicate that built it included such movieland notables as Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, Joseph Schenck, Louis B. Mayer, and Marcus Loew.

Throughout its history, the Hollywood Roosevelt has had a strong connection with the motion picture industry. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences had its first Merit Awards dinner in the Roosevelt’s Blossom Room on May 16, 1929. Marking the second anniversary of the founding of the Academy, this was the first time the Academy Awards were publicly presented. Today, the Blossom Room—with its Moorish columns, tiled walls, and muraled ceiling—is one of the hotel’s most beautiful spaces.

The Roosevelt has also been a radio and television studio. In the 1930s, Russ Columbo broadcast a national radio show from the Roosevelt’s Cinegrill—and in the 1950s and 1960s TV’s This Is Your Life came live from the hotel. The famous hotel has also been a location for numerous films, including Beverly Hills Cop II (1987), Internal Affairs (1990), and Charlie’s Angels 2 (2003). It is especially memorable in the 1998 version of Mighty Joe Young, where the monster ape climbs atop Grauman’s Chinese Theater while police helicopters circle the Roosevelt’s landmark Cinegrill neon sign.

Hollywood Boulevard—from Vista to Vine

In the 1880s, there were ranches, bean fields, orange and lemon groves. It was a peaceful, pastoral place—a far cry from the big city called Los Angeles that was growing up just five miles to the southeast. Staunchly conservative, early Hollywood was populated mostly with transplanted Midwesterners. One of these, a prohibitionist from Kansas named Harvey Wilcox, had some 120 acres that his wife had christened “Hollywood” because, so the story goes, she had met a woman on a train who had spoken in glowing terms of her summer home back East called Hollywood. When the Wilcoxes subdivided their property in 1887, the name that Mrs. Wilcox had so fancied was printed on the map advertising the lots the couple was selling for $150 an acre. Hollywood—like so many communities in Southern California—was officially launched as a real estate development.

The little community grew steadily, if not dramatically. By 1897, Hollywood had its own post office, and in 1903, the citizens (the population was now close to 700) voted to be incorporated as a city. One of the first things that the officials of this new little “sixth-class” city did was to enact a number of ordinances. Ranging from limiting the hours that billiard and pool rooms could be open to banning the sale of alcoholic beverages, Hollywood’s laws reflected the essential conservatism of its citizens. When this same citizenry voted in 1910 to have Hollywood annexed by the city of Los Angeles, it wasn’t out of any particular fondness for their worldly metropolitan neighbor; it was simply because they needed L.A.’s water and sewer system.

Needless to say, when the first movie folk came to town in 1911, these Eastern outsiders of questionable moral character were not exactly welcomed with open arms by Hollywood’s straitlaced locals. Indeed, in many ways, this Midwestern town that happened to be in Southern California was, except for the weather, an unlikely candidate to become the movie capital of the world.

Ironically, it was Hollywood’s conservatism that was indirectly responsible for its first movie studio. For when the Centaur Film Co. of Bayonne, New Jersey, arrived in California in 1911, they found a perfect setup for moviemaking in a former Hollywood tavern that had fallen on hard times owing to the town’s tough liquor laws. Besides its main building, the tavern property offered a barn and corral that would facilitate the shooting of Westerns, a group of small outbuildings that could be used as dressing rooms, and a bungalow for additional office space. Within a matter of days, the company was turning out three films a week from what they called the Nestor studio.

Universal’s founder, Carl Laemmle, was next on the Hollywood scene. Arriving in 1912, Laemmle set up his first West Coast base of operations on the southwest corner of Gower and Sunset, just across the street from the Nestor studio. A year later, a trio made up of Cecil B. DeMille, Jesse Lasky, and Samuel Goldfish (later Goldwyn) also settled in Hollywood and shot the town’s first feature-length film, The Squaw Man, based in a barn at the corner of Vine and Selma. As more and more movie people came, the locals who had at first looked down on the film business suddenly found themselves either directly in its employ or involved in businesses—from rooming houses to restaurants—that were making money thanks to motion pictures. In a word, Hollywood was booming—and the little Midwestern town in Southern California would never be the same again. By 1920, Hollywood’s population had grown to 36,000. By the end of the twenties it would swell to over 150,000.

As Hollywood made the transition from village to metropolis, a great boulevard kept pace with the new city’s growth and came to be the center of its wealth, power, and glory. Edged with movie palaces, stately hotels, glamorous restaurants and apartment buildings, Hollywood Boulevard was, in its heyday, one of the most dazzling thoroughfares in the country. The glamour started to wane in the late 1950s, however, and by the time the 1980s had rolled around this once great main street had lost much of its luster and parts of it had become home to punks, prostitutes, and panhandlers. It was then that concerned citizens and the local business community started taking action, realizing that the Boulevard’s ultimate glory lay in its past. Although there were differing visions of how best to revive the area, everyone agreed that something had to be done. In some ways, too, Hollywood Boulevard was unique because, owing to its long period of decline in the sixties and seventies, many architecturally distinguished buildings and theaters had not been torn down, as they had been in more thriving areas of Los Angeles. In other words, Hollywood Boulevard was a remarkably intact, if somewhat down-at-heels, monument to the city that would always be considered the motion picture capital of the world.

Happily, the last decade has been one of revival, with many of the Boulevard’s historic buildings now either restored or slated for restoration. Some have been turned into museums, whereas others are back to their original uses as theaters, restaurants, cafes, and nightclubs. At the same time, Hollywood Boulevard has welcomed a couple of new large-scale projects such as the Kodak Theatre, built to host the Academy Awards ceremonies, and the Hollywood & Highland complex, an entertainment mall designed in the spirit of a famous Old Hollywood movie set.

All this is not to say that Hollywood Boulevard has been totally sanitized. The old souvenir shops, fast-food outlets, tattoo parlors, and T-shirt emporiums are still very much a part of the mix—and the street’s funky charm. But whereas twenty years ago, when this book was originally published, finding the history that lurked on the movie capital’s main street was not easy. Today, it’s visible everywhere. And since so much of this history is connected with the film industry and its larger-than-life personalities, Hollywood Boulevard is a logical first stop in the movie lover’s Los Angeles odyssey. Here, a look at Hollywood’s main street and its new splendor, plus trips to some fascinating places beyond the Boulevard—from the legendary barn where The Squaw Man was shot back in 1913 to a secret enclave of Mediterranean houses where silent films stars once lived. Welcome to Hollywood—as it is now . . . and as it was then.

For convenient sightseeing, this first chapter covers Hollywood Boulevard and the vicinity from Vista to Vine Street. The best way to tour the Boulevard proper is on foot. To reach some of the places mentioned on Franklin Avenue and in the hills behind the Boulevard, a car is suggested.

1. Grauman’s Chinese Theater

6925 Hollywood Boulevard

Built by Hollywood developer C. E. Toberman for theater magnate Sid Grauman in 1927, the Chinese is the most famous movie house in the world. Reason? No other picture palace has ever come up with a publicity stunt as clever or successful as Grauman’s hallowed ritual of having movie stars leave their footprints, handprints, and autographs in the cement of the theater’s forecourt.

There are all sorts of stories as to how the custom began. The one most widely told is that silent screen star Norma Talmadge stopped by to tour the construction site and accidently stepped into some wet cement as she was getting out of her car. Another version says Grauman got the idea from Mary Pickford, who told him how her dog Zorro had gotten into some wet cement at her driveway up at Pickfair. “Now, we’ll have Zorro with us forever,” Pickford reportedly said to Grauman. Two days later, Grauman invited Pickford, her husband, Douglas Fairbanks, and Norma Talmadge to come celebrate the construction of his new theater with their prints and signatures. As these proved too faint upon drying, Grauman invited the same three stars as well as a few reporters back for an “official” ceremony. It made good copy—and indeed it still does.

Since that time, some 240 celebs have cemented their fame in the forecourt of the Chinese. Not all of the celebs have left just hand- and footprints: silent film star Harold Lloyd’s trademark glasses have been immortalized in cement here—as have Sonja Henie’s ice skates, John Wayne’s fist, Harpo Marx’s harp, Jimmy Durante’s nose, and one of Betty Grable’s “million-dollar” gams. Besides real-live people, Edgar Bergen’s dummy Charlie McCarthy has signed in at the Chinese; Roy Rogers’s horse Trigger and Gene Autry’s Champion have left hoofprints; Star Wars robots R2D2 and C3PO have rolled over the cement into immortality; and in 1984 Donald Duck marked his fiftieth birthday at the Chinese with two giant webbed-foot prints.

While movie lovers might question the credibility of some of the “legends” represented in the forecourt of the Chinese, few star presences have ever been publicly protested. A notable exception was Ali MacGraw’s December 1972 appearance at the theater, which was met by a small band of chanting and placard-carrying demonstrators who felt Ms. MacGraw’s lackluster four-film (at the time) career did not merit the full concrete treatment. (So far, though, Ms. MacGraw’s prints are still in place and have not wound up in the basement of the theater—the fate, according to insiders, that a number of the prints of some lesser legends are said to have met.)

There is more to the mystique of the Chinese Theater than footprints. Throughout its history, the theater has been one of Hollywood’s premier premiere places—ever since Cecil B. DeMille’s King of Kings opened the Chinese on May 27, 1927. Besides premieres, the theater hosted the Academy Awards in 1944, 1945, and 1946. The Chinese is also a treasure of movie theater architecture and interior design—and happily, after a $7 million restoration in 2001 by Mann Theatres, which has owned the Chinese since 1973, this 1920s picture palace is almost as splendid as it once was. Outside, the theater’s façade is a wonderful fantasy of a Chinese temple—complete with huge stone guard dogs on either side of the entrance and a sky-soaring pagoda roof. Inside, the lavish lobby and auditorium have marvelous murals, columns, Oriental vases, furniture, and carpets. It’s the kind of theater they just don’t build anymore—and simply being here makes up for anything that might be up on the screen.

Visit www.mann theatres.com

2. Mann’s Chinese 6 Theaters

6801 Hollywood Boulevard

Opened by Mann Theatres in 2001 to coincide with the debut of the restored Chinese Theater next door, this upscale multiplex features a stylish minimalist version of its legendary sibling’s Chinese decor as well as twenty-first-century amenities such as stadium seating, digital THX sound, and VIP lounges.

3. Hollywood Entertainment Museum

7021 Hollywood Boulevard

There’s something for everyone in this vast (32,000 square feet) exhibition hall’s assemblage of movie and television props, costumes, sets, and hands-on exhibits. TV fans can check out the Cheers barroom, the Star Trek Starship Enterprise control room, and Agent Mulder’s X-Files office. Sci-fi nuts can ogle forty years’ worth of monsters and scale models—from a Gort robot from The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) to the alien spacecraft from Independence Day (1996). Among the interactive exhib-

its, the Foley Room has visitors adding sound effects to a film

sequence. In addition to its permanent displays, the museum

features excellent special shows such as “Marlene Dietrich:

Treasures from the Estate Collection”; “Smoke, Lies, and Vid-eotape,” which documented Hollywood’s role in glamorizing smoking; and “USO Presenting Hollywood Salutes the Troops,” focusing on legendary USO shows from World War II up to the war in Afghanistan.

For current museum hours and information on special exhibitions, call 323–465–7900 and visit www.hollywoodmuseum.com.

4. The Walk of Fame

If Grauman’s Chinese Theater could achieve world renown through its sidewalk—why not all of Hollywood? At least, that’s what a group of local business people thought in the late 1950s when they concocted a scheme to turn the sidewalks of a deteriorating Hollywood Boulevard into a vast star-studded terrazzo commemorating the legends of the film, radio, television, and recording industries. Shop and property owners along the proposed walkway were asked to contribute $85 per front foot and $1.25 million was raised to begin the project that initially immortalized 1,558 personalities and continues to do so at the rate of about fifteen to twenty stars a year. (There are now more than 2,200.)

In 1983, theater was added as a fifth Walk of Fame category and Mickey Rooney, then starring in Sugar Babies at Hollywood’s Pantages Theater, became the first “two-star” celebrity when he was given his second star for his recent theatrical success. To make the Walk of Fame, new stars must be sponsored—by their agents, their producers, their fan clubs, or a local business—for the honor. A special committee of the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce then votes on the candidate’s acceptability, taking into consideration professional as well as humanitarian achievements. If the candidate fulfills the requirements, the sponsor pays approximately $15,000 to cover the cost of the star, the ceremony that goes along with it, and the Walk’s ongoing maintenance and repairs.

The Walk of Fame extends for some two and a half miles from La Brea to Gower along both sides of Hollywood Boulevard and from Sunset to Yucca along Vine Street.

Dedication ceremonies for the Walk of Fame are usually held at noon on the third Thursday of each month. Check with the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce for exact times and locations by calling 323–469–8311.

5. Hollywood Gateway Sculpture

Hollywood Boulevard/La Brea Avenue

Erected in 1993 on the strategic corner of Hollywood Boulevard and La Brea Avenue—often considered the western “gateway” to downtown Hollywood—this striking installation by artists Catherine Hardwicke and Hari West pays politically correct homage to four screen goddesses, each from a different ethnic background. The women, their gigantic stainless-steel images holding up a 30-foot gazebo, are Mae West, Dorothy Dandridge, Anna May Wong, and Delores Del Rio. The whole concoction is topped by a tiny Marilyn Monroe weathervane.

6. Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel

7000 Hollywood Boulevard

A 1927 newspaper ad touted its grand opening as “the dominant social occasion of the year.” “Don’t wait,” it enthused. “You will see the greatest number of stage and screen stars ever assembled.” Among those invited were: Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, Norma Talmadge, Constance Talmadge, Pola Negri, Richard Barthelmess, John Gilbert, Harold Lloyd, Greta Garbo, Gloria Swanson, Rod La Rocque, Janet Gaynor, Will Rogers, Clara Bow, Sid Chaplin, Sid Grauman, Wallace Beery, Charles Chaplin . . . and scores of others. And most of them came—not only because, at twelve stories and four hundred rooms, this was the most impressive hotel ever to be built in Hollywood, but also because the syndicate that built it included such movieland notables as Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, Joseph Schenck, Louis B. Mayer, and Marcus Loew.

Throughout its history, the Hollywood Roosevelt has had a strong connection with the motion picture industry. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences had its first Merit Awards dinner in the Roosevelt’s Blossom Room on May 16, 1929. Marking the second anniversary of the founding of the Academy, this was the first time the Academy Awards were publicly presented. Today, the Blossom Room—with its Moorish columns, tiled walls, and muraled ceiling—is one of the hotel’s most beautiful spaces.

The Roosevelt has also been a radio and television studio. In the 1930s, Russ Columbo broadcast a national radio show from the Roosevelt’s Cinegrill—and in the 1950s and 1960s TV’s This Is Your Life came live from the hotel. The famous hotel has also been a location for numerous films, including Beverly Hills Cop II (1987), Internal Affairs (1990), and Charlie’s Angels 2 (2003). It is especially memorable in the 1998 version of Mighty Joe Young, where the monster ape climbs atop Grauman’s Chinese Theater while police helicopters circle the Roosevelt’s landmark Cinegrill neon sign.

Descriere

For the consummate movie buff, this guide reveals not only famous movie scenes shot in glamorous L.A., but also all the scenes readers didn't know were shot in Hollywood.