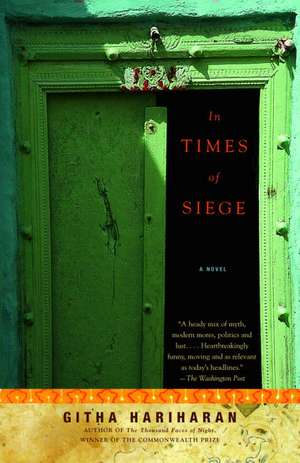

In Times of Siege: Vintage Contemporaries

Autor Githa Hariharanen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2004

Din seria Vintage Contemporaries

-

Preț: 109.95 lei

Preț: 109.95 lei -

Preț: 101.80 lei

Preț: 101.80 lei -

Preț: 96.52 lei

Preț: 96.52 lei -

Preț: 107.46 lei

Preț: 107.46 lei -

Preț: 91.77 lei

Preț: 91.77 lei -

Preț: 101.88 lei

Preț: 101.88 lei -

Preț: 111.51 lei

Preț: 111.51 lei -

Preț: 119.87 lei

Preț: 119.87 lei -

Preț: 99.75 lei

Preț: 99.75 lei -

Preț: 97.34 lei

Preț: 97.34 lei -

Preț: 111.92 lei

Preț: 111.92 lei -

Preț: 117.87 lei

Preț: 117.87 lei -

Preț: 95.92 lei

Preț: 95.92 lei -

Preț: 113.56 lei

Preț: 113.56 lei -

Preț: 132.88 lei

Preț: 132.88 lei -

Preț: 108.09 lei

Preț: 108.09 lei -

Preț: 115.42 lei

Preț: 115.42 lei -

Preț: 106.04 lei

Preț: 106.04 lei -

Preț: 96.11 lei

Preț: 96.11 lei -

Preț: 90.64 lei

Preț: 90.64 lei -

Preț: 87.84 lei

Preț: 87.84 lei -

Preț: 99.60 lei

Preț: 99.60 lei -

Preț: 105.41 lei

Preț: 105.41 lei -

Preț: 99.30 lei

Preț: 99.30 lei -

Preț: 120.26 lei

Preț: 120.26 lei -

Preț: 103.74 lei

Preț: 103.74 lei -

Preț: 100.98 lei

Preț: 100.98 lei -

Preț: 100.76 lei

Preț: 100.76 lei -

Preț: 89.09 lei

Preț: 89.09 lei -

Preț: 115.94 lei

Preț: 115.94 lei -

Preț: 101.24 lei

Preț: 101.24 lei -

Preț: 125.13 lei

Preț: 125.13 lei -

Preț: 89.50 lei

Preț: 89.50 lei -

Preț: 100.35 lei

Preț: 100.35 lei -

Preț: 139.63 lei

Preț: 139.63 lei -

Preț: 90.35 lei

Preț: 90.35 lei -

Preț: 106.45 lei

Preț: 106.45 lei -

Preț: 89.91 lei

Preț: 89.91 lei -

Preț: 107.92 lei

Preț: 107.92 lei -

Preț: 77.02 lei

Preț: 77.02 lei -

Preț: 125.21 lei

Preț: 125.21 lei -

Preț: 96.93 lei

Preț: 96.93 lei -

Preț: 112.11 lei

Preț: 112.11 lei -

Preț: 83.94 lei

Preț: 83.94 lei -

Preț: 97.15 lei

Preț: 97.15 lei -

Preț: 105.82 lei

Preț: 105.82 lei -

Preț: 88.62 lei

Preț: 88.62 lei -

Preț: 111.76 lei

Preț: 111.76 lei -

Preț: 129.78 lei

Preț: 129.78 lei -

Preț: 100.57 lei

Preț: 100.57 lei

Preț: 72.58 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 109

Preț estimativ în valută:

13.89€ • 14.54$ • 11.49£

13.89€ • 14.54$ • 11.49£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400033379

ISBN-10: 1400033373

Pagini: 224

Dimensiuni: 134 x 204 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: VINTAGE BOOKS

Seria Vintage Contemporaries

ISBN-10: 1400033373

Pagini: 224

Dimensiuni: 134 x 204 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: VINTAGE BOOKS

Seria Vintage Contemporaries

Notă biografică

Githa Hariharan was educated in Bombay, Manila, and the United States. She has worked in public television in the United States and as an editor in India. Her first novel, The Thousand Faces of Night, won the Commonwealth Writers Prize. Since then, she has published a collection of short stories, The Art of Dying, and two novels, The Ghosts of Vasu Master and When Dreams Travel. She lives in New Delhi.

Extras

ONE

New Delhi

AUGUST 23, 2000

South Gate. Shiv's car slows down, goes past the security booth, then over a series of unmarked humps. A ramshackle old Fiat passes by.

Ahead a wheezing bus snorts its way toward him. A cycle follows.

Otherwise the road, as far as he can see, is setting for more human traffic. Boys and girls--or, he corrects himself, young men and women. Dozens of them, some sitting on the pavement, staring frankly at the world going by, some daydreaming at the bus stop. A few clustered round the dhaba by the road, drinking tea and smoking. Though he is the visitor, it is they who look at him like well-briefed sightseers viewing a tourist staple. A teacher, a faculty type, a familiar monument in a city of ruins.

The university. A gate, a winding road, young faces, straight limbs. The city yields its claims. Delhi, an insatiable amoeba that grows in all directions, recedes.

Here too the trees and bushes that border the road on either side look vulnerable to the spite of the late summer sun. But the university's green--prolific, variegated--has penetrated the landscape into the heart of its texture. Here green fingers colonize the buildings. Brick is generously streaked with ivy and creepers, or curtained by clumps of untrimmed bushes. Though Shiv can't tell from the road, the buildings look as if they might be hospitable to birds' nests, cobwebs, beehives.

He feels a twinge of wonder and excitement, like a boy hungry for adventure, a castaway in an island where all the natives are young. An island in landlocked Delhi, no mean marvel. You could arrive here from the railway station, a pliant piece of clay to be molded, live the last and best years of childhood. Then take a direct bus, the 615, to deliver you back at the station. Delhi need be seen only from a bus window, its imperial avenues, its filth-ridden hovels and concrete monstrosities reduced to the powerless, fleeting images of a dream.

He sees two girls--no, a woman and a girl--wave at him to stop.

Though the hostel he is going to cannot be far away, he slows down and comes to a halt. The younger one runs up to his window, her long hair and her diaphanous blue dupatta flying behind her.

"Are you going up-campus?" she asks. Her voice is shrill and breathless.

He is tempted to find out how far he will have to go, which hill he will have to climb to reach this up-campus. But he shakes his head, apologizes.

She turns to pull a face at the other woman who is already peering into the distance, on the lookout for another car.

"I am looking for a hostel," he tells the girl and she turns back to him impatiently. "Jamuna Ladies' Hostel--I mean women's hostel. Would you tell me where that is?"

She points to a building behind the trees, then runs back to her companion.

The hostel building is at the end of a lane to the left. Its face is lined with balconies full of clothes hung out to dry. He parks under a tree, fitting the car neatly into a small patch of shade, and walks slowly to the open gate. He waits till he sees a girl going in. Her back is a jar-shape stuffed into faded blue jeans.

"Please," he says to the jar, and it turns around, revealing a moonface that belongs in an old Hindi film. "Please," he says to this siren in the wrong costume, "could you tell Meena, R. Meena, that her guardian is waiting for her at the gate?"

Moonface looks him up and down with undisguised curiosity. "She's broken her knee," she volunteers.

"I know, that's why I am here. I've come to take her home."

The girl nods at him. From her face it is clear that her curiosity has been instantly appeased. She disappears into the building.

Shiv stands there, looking around him.

Though he too lives in a university, it is a world apart from this living, breathing mass of students. Where he teaches, only the teachers are visible. The students are names, addresses, postmarks. Part of what is called, oddly, an Open University, as if the gates are perpetually open and the students have wandered away. Though there are no resident students, his campus is even larger than this one. He lives at the south end of his campus, a rocky, partially cleared stretch of jungle that the professors share with noisy peacocks, and the occasional snake, jackal and monkey. He drives to the "academic complex" in the north part of the campus, to sit every day in an office with an intimidating bilingual nameplate on the door: Professor Shivamurthy in English, Shiv Murthy in Hindi. He is, at fifty-two, finally a professor of history, though not quite the sort his father imagined in daydreams on his behalf. He no longer teaches students; as his Department Head likes to put it, he coordinates resources for his educational clients.

Shiv shifts from leg to leg restlessly. He can sense someone watching him.

He turns around and notices a tiny makeshift shop across the road, nestled under a tree. It sells newspapers, beedi and cigarettes, and the garishly colored packets of junk food that have been hung out on display.

The shopkeeper, a young man in need of excitement, stands outside his shop staring at Shiv. His gaze is hopeful, as if he expects Shiv to do something in the next few minutes that will make today less boring than yesterday. Then, as the young man watches Shiv do nothing, he moves his hand casually toward his crotch and scratches himself. The expectant look on his face turns thoughtful.

Shiv concedes defeat in their staring competition and turns back to the hostel gate. There is no guard at the gate, though he is sure there is usually one, the sort with a lathi, protecting that holy of holies, a girls' hostel. Perhaps he should waylay someone else going into the hostel and ask her why the girl is taking so long.

The girl. When she first came to Kamala Nehru University in Delhi two, three years back, her mother wrote to Shiv asking if he would be her daughter's "local guardian." He didn't know what this would involve, and quickly passed the letter to Rekha. His wife, Rekha, with the efficiency that makes her an administrative asset in her office, took over. Not that she had much to do. She picked up the girl from her hostel on a Sunday and took her to Sarojini Nagar to buy bargain woolens for her first Delhi winter. Then brought her home for lunch.

The girl did not have much to say for herself--Shiv can't remember having a conversation with her. She seemed watchful though, as if assessing their faces, their words, the spare but impeccable living room, their hospitality. About the only thing Shiv recalls is her silent but enthusiastic feeding at lunch. Rekha called her a few times after that, and perhaps the girl did come home again, though he is not sure of that. He does remember that the girl seemed self-sufficient. She was always too busy to visit them on Sundays--the only day Rekha could have guests for lunch--and Shiv had all but forgotten he was her guardian till the telephone call yesterday.

"You don't know me," said a girl's voice on the phone. "I am a friend of Meena's."

It took Shiv a moment to remember who Meena was. Then foolishly he said the first thing that came to his mind. "I am sorry," he said. "My wife is not in town."

There was a nonplussed silence from the girl, and he recovered himself to ask, "Is something wrong? Is Meena all right?"

The girl replied in a burst of relief, "No, she's not. She fell off a bus and she's broken her knee. She wants you to come and get her from the hostel. Jamuna Girls' Hostel. Room 15. It's very difficult for her here, she has a huge cast and she can't manage. When can you come?"

"Tomorrow. Tomorrow afternoon. How long will she be in the cast?"

"I'm not sure, but I think the doctor said at least three or four weeks. I'll pack her things for her by tomorrow."

Shiv moves closer to the open gate, peers in. Why is the girl taking so long? He was hoping to take her home, settle her in the room downstairs, and get back to the Department. (They may not have classroom hours where he teaches, but they are devoted to office hours.) If the girl needs anything while he is away, there's Kamla in the servants' quarters at the back. And tonight he will have to call her parents if she hasn't already done that. Her parents will probably want to take her home, though he will, for the sake of courtesy, offer to have mother and daughter stay with him till Meena is better. But really, without Rekha, two guests in the house, one with a broken leg--Shiv steps into the hostel grounds warily, half expecting someone to emerge from the building and stop him from taking a step further.

Then three girls emerge as if on signal; one of them is Meena on crutches. Shiv forgets his fear of rules in girls' hostels and goes toward them.

As he approaches them, all three girls stop and look at him. The frame freezes there.

Shiv will always remember this image, three girls, a stranger on either side of Meena, a look in their unblinking eyes that makes him hesitate--as if he is on the brink of something, something that cannot be undone. He will always remember the silent challenge in their eyes: Here you are, the man, the savior of one-legged girls. Well? Do what you have to, act your role!

Then Shiv sees the small battered suitcase, and he is able to move again, having seen where his task lies. He takes the suitcase from the girl holding it; it is surprisingly light. His ward travels light, unlike his wife and daughter, both of whom pack heavily and comprehensively for all occasions.

They move in a slow, solemn procession to the car; Shiv leads the way with the suitcase. He opens the nearest door to the backseat and waits.

"How do I get in?" These are Meena's first words to him. Only now it occurs to him that they have not greeted each other, nor has she thanked him for coming. Shiv's heart sinks; it is bad enough to have to play good Samaritan, but to cope with silence and perhaps sullenness as well?

"Sit on the edge of the seat, sideways, then crawl back on your bum," advises one of the girls. Clearly she is the competent sort who always knows what she is talking about.

Meena does this, slowly, the muscles on her face taut with the strain, her mouth open, breathing shallowly. Shiv shuts the door gently but still he sees her wince. His Maruti is too small for a body; he sees this for the first time. She sits as if boxed in a cupboard shelf, her feet flexed against the car door.

"All right?" he asks, and unexpectedly, she smiles a sweet, rueful smile.

"No, but let's go," she replies.

Shiv drives self-consciously, aware of her discomfort every time he goes over a hump or into a pothole. "Sorry," he says a few times, but then it seems pointless. The road is an obstacle course all the way from her KNU, a vibrant island of green, to the arid stretches of his KGU.

Shiv can sense the overwhelming relief in the car, his and hers, as they finally approach his driveway an hour later.

Getting out of the car proves more difficult than getting in, especially without the practical friend's advice. Shiv holds the girl's moist, clammy hand while she grunts her way forward to the edge of the seat. Then with a final grunt she pulls herself up and totters on one foot. He holds on to her, looking round wildly for the crutches. She is heavier than he expected. With her weight on him, Shiv too can feel a groan coming to his lips--as if it is infectious--and he leans forward to get the crutches lying on the car floor.

The wooden crutches are relics from a medieval medical kit. They belong ostentatiously to a past that has long been used up. The stuffing on top of one has entirely given way. Its entrails hang out, desolate twisted rags. The cushion of the other crutch has patches of its original covering, midway in the process of green turning to brown. The fake leather covering has an oily look to it, memories of the many armpits it has supported. The two crutches are of unequal height, and one has lost its rubber foot.

Shiv and the girl move together clumsily to the front door and he hastens to unlock it.

Now that she is here, Shiv's preparations seem woefully inadequate. He has made the bed in the little room downstairs, remembered to keep a bottle of water and a glass on the table by the bed. But the room that greets them is a small dark hole. He can see the dust on the table around the bottle. A pair of large, elegant mosquitoes sit on the wall by the bed like a reception committee.

But she does not seem to notice any of this. He can hear her sigh as he helps her into bed. She stretches out her legs and shuts her eyes.

Shiv hesitates, wondering if he should cover her, or get her something to eat or drink. He waits, but her eyes remain shut. Shiv notices two little holes side by side on her faded gray T-shirt. Her face, a smooth brown mask, looks young and weary, a combination he has not seen before.

On an impulse, Shiv leaves the room and goes looking for Rekha's brass bell, a bell his mother used at her endless pujas to call the deaf gods to attention. The bell, having failed to perform its real function, now sits polished and gleaming, an object on exhibit in the living room of a nonpraying household. Its magic may have failed, but it does well as an arty object. Shiv returns with the bell, places it by the water bottle on the table. He puts away the ancient crutches in a corner and keeps a walking stick instead by her bed.

He takes one more look at her, willing her to open her eyes and say something. But she remains still, oblivious of his presence. Suddenly Shiv feels like an intruder in his own house. He switches off the lamp on the table and leaves the room, half-shutting the door behind him.

From the Hardcover edition.

New Delhi

AUGUST 23, 2000

South Gate. Shiv's car slows down, goes past the security booth, then over a series of unmarked humps. A ramshackle old Fiat passes by.

Ahead a wheezing bus snorts its way toward him. A cycle follows.

Otherwise the road, as far as he can see, is setting for more human traffic. Boys and girls--or, he corrects himself, young men and women. Dozens of them, some sitting on the pavement, staring frankly at the world going by, some daydreaming at the bus stop. A few clustered round the dhaba by the road, drinking tea and smoking. Though he is the visitor, it is they who look at him like well-briefed sightseers viewing a tourist staple. A teacher, a faculty type, a familiar monument in a city of ruins.

The university. A gate, a winding road, young faces, straight limbs. The city yields its claims. Delhi, an insatiable amoeba that grows in all directions, recedes.

Here too the trees and bushes that border the road on either side look vulnerable to the spite of the late summer sun. But the university's green--prolific, variegated--has penetrated the landscape into the heart of its texture. Here green fingers colonize the buildings. Brick is generously streaked with ivy and creepers, or curtained by clumps of untrimmed bushes. Though Shiv can't tell from the road, the buildings look as if they might be hospitable to birds' nests, cobwebs, beehives.

He feels a twinge of wonder and excitement, like a boy hungry for adventure, a castaway in an island where all the natives are young. An island in landlocked Delhi, no mean marvel. You could arrive here from the railway station, a pliant piece of clay to be molded, live the last and best years of childhood. Then take a direct bus, the 615, to deliver you back at the station. Delhi need be seen only from a bus window, its imperial avenues, its filth-ridden hovels and concrete monstrosities reduced to the powerless, fleeting images of a dream.

He sees two girls--no, a woman and a girl--wave at him to stop.

Though the hostel he is going to cannot be far away, he slows down and comes to a halt. The younger one runs up to his window, her long hair and her diaphanous blue dupatta flying behind her.

"Are you going up-campus?" she asks. Her voice is shrill and breathless.

He is tempted to find out how far he will have to go, which hill he will have to climb to reach this up-campus. But he shakes his head, apologizes.

She turns to pull a face at the other woman who is already peering into the distance, on the lookout for another car.

"I am looking for a hostel," he tells the girl and she turns back to him impatiently. "Jamuna Ladies' Hostel--I mean women's hostel. Would you tell me where that is?"

She points to a building behind the trees, then runs back to her companion.

The hostel building is at the end of a lane to the left. Its face is lined with balconies full of clothes hung out to dry. He parks under a tree, fitting the car neatly into a small patch of shade, and walks slowly to the open gate. He waits till he sees a girl going in. Her back is a jar-shape stuffed into faded blue jeans.

"Please," he says to the jar, and it turns around, revealing a moonface that belongs in an old Hindi film. "Please," he says to this siren in the wrong costume, "could you tell Meena, R. Meena, that her guardian is waiting for her at the gate?"

Moonface looks him up and down with undisguised curiosity. "She's broken her knee," she volunteers.

"I know, that's why I am here. I've come to take her home."

The girl nods at him. From her face it is clear that her curiosity has been instantly appeased. She disappears into the building.

Shiv stands there, looking around him.

Though he too lives in a university, it is a world apart from this living, breathing mass of students. Where he teaches, only the teachers are visible. The students are names, addresses, postmarks. Part of what is called, oddly, an Open University, as if the gates are perpetually open and the students have wandered away. Though there are no resident students, his campus is even larger than this one. He lives at the south end of his campus, a rocky, partially cleared stretch of jungle that the professors share with noisy peacocks, and the occasional snake, jackal and monkey. He drives to the "academic complex" in the north part of the campus, to sit every day in an office with an intimidating bilingual nameplate on the door: Professor Shivamurthy in English, Shiv Murthy in Hindi. He is, at fifty-two, finally a professor of history, though not quite the sort his father imagined in daydreams on his behalf. He no longer teaches students; as his Department Head likes to put it, he coordinates resources for his educational clients.

Shiv shifts from leg to leg restlessly. He can sense someone watching him.

He turns around and notices a tiny makeshift shop across the road, nestled under a tree. It sells newspapers, beedi and cigarettes, and the garishly colored packets of junk food that have been hung out on display.

The shopkeeper, a young man in need of excitement, stands outside his shop staring at Shiv. His gaze is hopeful, as if he expects Shiv to do something in the next few minutes that will make today less boring than yesterday. Then, as the young man watches Shiv do nothing, he moves his hand casually toward his crotch and scratches himself. The expectant look on his face turns thoughtful.

Shiv concedes defeat in their staring competition and turns back to the hostel gate. There is no guard at the gate, though he is sure there is usually one, the sort with a lathi, protecting that holy of holies, a girls' hostel. Perhaps he should waylay someone else going into the hostel and ask her why the girl is taking so long.

The girl. When she first came to Kamala Nehru University in Delhi two, three years back, her mother wrote to Shiv asking if he would be her daughter's "local guardian." He didn't know what this would involve, and quickly passed the letter to Rekha. His wife, Rekha, with the efficiency that makes her an administrative asset in her office, took over. Not that she had much to do. She picked up the girl from her hostel on a Sunday and took her to Sarojini Nagar to buy bargain woolens for her first Delhi winter. Then brought her home for lunch.

The girl did not have much to say for herself--Shiv can't remember having a conversation with her. She seemed watchful though, as if assessing their faces, their words, the spare but impeccable living room, their hospitality. About the only thing Shiv recalls is her silent but enthusiastic feeding at lunch. Rekha called her a few times after that, and perhaps the girl did come home again, though he is not sure of that. He does remember that the girl seemed self-sufficient. She was always too busy to visit them on Sundays--the only day Rekha could have guests for lunch--and Shiv had all but forgotten he was her guardian till the telephone call yesterday.

"You don't know me," said a girl's voice on the phone. "I am a friend of Meena's."

It took Shiv a moment to remember who Meena was. Then foolishly he said the first thing that came to his mind. "I am sorry," he said. "My wife is not in town."

There was a nonplussed silence from the girl, and he recovered himself to ask, "Is something wrong? Is Meena all right?"

The girl replied in a burst of relief, "No, she's not. She fell off a bus and she's broken her knee. She wants you to come and get her from the hostel. Jamuna Girls' Hostel. Room 15. It's very difficult for her here, she has a huge cast and she can't manage. When can you come?"

"Tomorrow. Tomorrow afternoon. How long will she be in the cast?"

"I'm not sure, but I think the doctor said at least three or four weeks. I'll pack her things for her by tomorrow."

Shiv moves closer to the open gate, peers in. Why is the girl taking so long? He was hoping to take her home, settle her in the room downstairs, and get back to the Department. (They may not have classroom hours where he teaches, but they are devoted to office hours.) If the girl needs anything while he is away, there's Kamla in the servants' quarters at the back. And tonight he will have to call her parents if she hasn't already done that. Her parents will probably want to take her home, though he will, for the sake of courtesy, offer to have mother and daughter stay with him till Meena is better. But really, without Rekha, two guests in the house, one with a broken leg--Shiv steps into the hostel grounds warily, half expecting someone to emerge from the building and stop him from taking a step further.

Then three girls emerge as if on signal; one of them is Meena on crutches. Shiv forgets his fear of rules in girls' hostels and goes toward them.

As he approaches them, all three girls stop and look at him. The frame freezes there.

Shiv will always remember this image, three girls, a stranger on either side of Meena, a look in their unblinking eyes that makes him hesitate--as if he is on the brink of something, something that cannot be undone. He will always remember the silent challenge in their eyes: Here you are, the man, the savior of one-legged girls. Well? Do what you have to, act your role!

Then Shiv sees the small battered suitcase, and he is able to move again, having seen where his task lies. He takes the suitcase from the girl holding it; it is surprisingly light. His ward travels light, unlike his wife and daughter, both of whom pack heavily and comprehensively for all occasions.

They move in a slow, solemn procession to the car; Shiv leads the way with the suitcase. He opens the nearest door to the backseat and waits.

"How do I get in?" These are Meena's first words to him. Only now it occurs to him that they have not greeted each other, nor has she thanked him for coming. Shiv's heart sinks; it is bad enough to have to play good Samaritan, but to cope with silence and perhaps sullenness as well?

"Sit on the edge of the seat, sideways, then crawl back on your bum," advises one of the girls. Clearly she is the competent sort who always knows what she is talking about.

Meena does this, slowly, the muscles on her face taut with the strain, her mouth open, breathing shallowly. Shiv shuts the door gently but still he sees her wince. His Maruti is too small for a body; he sees this for the first time. She sits as if boxed in a cupboard shelf, her feet flexed against the car door.

"All right?" he asks, and unexpectedly, she smiles a sweet, rueful smile.

"No, but let's go," she replies.

Shiv drives self-consciously, aware of her discomfort every time he goes over a hump or into a pothole. "Sorry," he says a few times, but then it seems pointless. The road is an obstacle course all the way from her KNU, a vibrant island of green, to the arid stretches of his KGU.

Shiv can sense the overwhelming relief in the car, his and hers, as they finally approach his driveway an hour later.

Getting out of the car proves more difficult than getting in, especially without the practical friend's advice. Shiv holds the girl's moist, clammy hand while she grunts her way forward to the edge of the seat. Then with a final grunt she pulls herself up and totters on one foot. He holds on to her, looking round wildly for the crutches. She is heavier than he expected. With her weight on him, Shiv too can feel a groan coming to his lips--as if it is infectious--and he leans forward to get the crutches lying on the car floor.

The wooden crutches are relics from a medieval medical kit. They belong ostentatiously to a past that has long been used up. The stuffing on top of one has entirely given way. Its entrails hang out, desolate twisted rags. The cushion of the other crutch has patches of its original covering, midway in the process of green turning to brown. The fake leather covering has an oily look to it, memories of the many armpits it has supported. The two crutches are of unequal height, and one has lost its rubber foot.

Shiv and the girl move together clumsily to the front door and he hastens to unlock it.

Now that she is here, Shiv's preparations seem woefully inadequate. He has made the bed in the little room downstairs, remembered to keep a bottle of water and a glass on the table by the bed. But the room that greets them is a small dark hole. He can see the dust on the table around the bottle. A pair of large, elegant mosquitoes sit on the wall by the bed like a reception committee.

But she does not seem to notice any of this. He can hear her sigh as he helps her into bed. She stretches out her legs and shuts her eyes.

Shiv hesitates, wondering if he should cover her, or get her something to eat or drink. He waits, but her eyes remain shut. Shiv notices two little holes side by side on her faded gray T-shirt. Her face, a smooth brown mask, looks young and weary, a combination he has not seen before.

On an impulse, Shiv leaves the room and goes looking for Rekha's brass bell, a bell his mother used at her endless pujas to call the deaf gods to attention. The bell, having failed to perform its real function, now sits polished and gleaming, an object on exhibit in the living room of a nonpraying household. Its magic may have failed, but it does well as an arty object. Shiv returns with the bell, places it by the water bottle on the table. He puts away the ancient crutches in a corner and keeps a walking stick instead by her bed.

He takes one more look at her, willing her to open her eyes and say something. But she remains still, oblivious of his presence. Suddenly Shiv feels like an intruder in his own house. He switches off the lamp on the table and leaves the room, half-shutting the door behind him.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“A heady mix of myth, modern mores, politics and lust. . . . Heartbreakingly funny, moving and as relevant as today’s headlines.”—The Washington Post

“Githa Hariharan’s fiction is wonderful—full of subtleties and humor and tenderness.” –Michael Ondaatje

“If this premise seems to be drawn from the headlines of modern, B.J.P.-dominated India, Hariharan amplifies the themes of courage, dissent, and responsibility in her protagonist’s private life. . . . The result is an engaging portrait of the mild-mannered professor.” –The New Yorker

“Appealing. . . . By turns bewildered, titillated, embarrassed, and frightened out of his wits, Shiv makes a sweetly sympathetic hero for a story that is part comedy of manners, part comedy of ideas.”—The Boston Globe

"A modern fable . . . beautifully told in a spare style that is as modern as its subject."--The Baltimore Sun

"A witty, insightful novel . . . Hariharan tells the tale with a realistic grasp of how people interact and a highly evolved sense of the absurd." --The Seattle Times

“Intelligent . . . [Hariharan’s] deceptively simple prose belies the artistry of her phrasings and she writes with an infectious concern for her characters.” --San Francisco Chronicle

“Admirable. [Its] themes . . . extend beyond India or its current situation. They are universal. Ms. Hariharan has written a fine novel that leaves much to ponder long after its conclusion.” –The Richmond-Times Dispatch

“[Hariharan is] an outstanding writer.” –J. M. Coetzee

“Eloquently written . . . a quick read, and fascinating to any outsider. A modern book, it reads like a classic with gorgeous prose and intense conflict.” –The Oklahoma Gazette

"Imaginative . . . entertaining . . . [The] strength of this highly readable tale is that it is a delicate blend of humor, tenderness and insight." --Tucson Citizen

“Wonderful . . . Ms. Hariharan executes the vastness of India’s historical terrain, and the minutiae of one sagging human being finding a flicker of inspiration, with great dignity and intimate humor.” –The Asian Reporter

"Engrossing . . . re-establishes [Hariharan's] reputation as a deft storyteller." --India-West

“Hariharan captures Shiv’s besieged existence with just the right amount of angst, confusion, polemic and humour. Hariharan has written . . . [a] persuasive work that tells of the perils of sectarianism and silence in the face of oppression.” –Far Eastern Economic Review

“Hariharan writes with anguish, pain and anger about what is happening to our country. I put In Times of Siege on top of my list of books that must be read.” –Khushwant Singh in The Hindustan Times

“Githa Hariharan’s fiction is wonderful—full of subtleties and humor and tenderness.” –Michael Ondaatje

“If this premise seems to be drawn from the headlines of modern, B.J.P.-dominated India, Hariharan amplifies the themes of courage, dissent, and responsibility in her protagonist’s private life. . . . The result is an engaging portrait of the mild-mannered professor.” –The New Yorker

“Appealing. . . . By turns bewildered, titillated, embarrassed, and frightened out of his wits, Shiv makes a sweetly sympathetic hero for a story that is part comedy of manners, part comedy of ideas.”—The Boston Globe

"A modern fable . . . beautifully told in a spare style that is as modern as its subject."--The Baltimore Sun

"A witty, insightful novel . . . Hariharan tells the tale with a realistic grasp of how people interact and a highly evolved sense of the absurd." --The Seattle Times

“Intelligent . . . [Hariharan’s] deceptively simple prose belies the artistry of her phrasings and she writes with an infectious concern for her characters.” --San Francisco Chronicle

“Admirable. [Its] themes . . . extend beyond India or its current situation. They are universal. Ms. Hariharan has written a fine novel that leaves much to ponder long after its conclusion.” –The Richmond-Times Dispatch

“[Hariharan is] an outstanding writer.” –J. M. Coetzee

“Eloquently written . . . a quick read, and fascinating to any outsider. A modern book, it reads like a classic with gorgeous prose and intense conflict.” –The Oklahoma Gazette

"Imaginative . . . entertaining . . . [The] strength of this highly readable tale is that it is a delicate blend of humor, tenderness and insight." --Tucson Citizen

“Wonderful . . . Ms. Hariharan executes the vastness of India’s historical terrain, and the minutiae of one sagging human being finding a flicker of inspiration, with great dignity and intimate humor.” –The Asian Reporter

"Engrossing . . . re-establishes [Hariharan's] reputation as a deft storyteller." --India-West

“Hariharan captures Shiv’s besieged existence with just the right amount of angst, confusion, polemic and humour. Hariharan has written . . . [a] persuasive work that tells of the perils of sectarianism and silence in the face of oppression.” –Far Eastern Economic Review

“Hariharan writes with anguish, pain and anger about what is happening to our country. I put In Times of Siege on top of my list of books that must be read.” –Khushwant Singh in The Hindustan Times