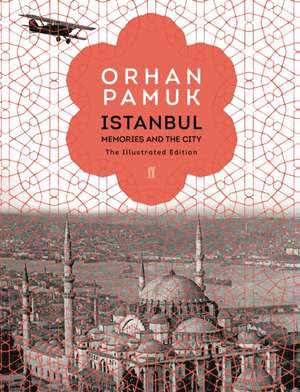

Istanbul

Autor Orhan Pamuken Limba Engleză Hardback – 5 oct 2017

This lavish selection of 450 photographs features contributions from Ara Güler, Henri Cartier-Bresson and Istanbul's characteristic photography collectors, and contains previously unpublished family photographs from the author's archives.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 59.70 lei 24-36 zile | +35.27 lei 4-10 zile |

| FABER AND FABER LTD – apr 2006 | 59.70 lei 24-36 zile | +35.27 lei 4-10 zile |

| Vintage Books USA – 30 iun 2006 | 108.16 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| Hardback (1) | 211.95 lei 3-5 săpt. | +60.31 lei 4-10 zile |

| FABER & FABER – 5 oct 2017 | 211.95 lei 3-5 săpt. | +60.31 lei 4-10 zile |

Preț: 211.95 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 318

Preț estimativ în valută:

40.55€ • 42.35$ • 33.49£

40.55€ • 42.35$ • 33.49£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 25 martie-08 aprilie

Livrare express 08-14 martie pentru 70.30 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780571330348

ISBN-10: 0571330347

Pagini: 624

Dimensiuni: 182 x 241 x 58 mm

Greutate: 1.37 kg

Ediția:Main

Editura: FABER & FABER

ISBN-10: 0571330347

Pagini: 624

Dimensiuni: 182 x 241 x 58 mm

Greutate: 1.37 kg

Ediția:Main

Editura: FABER & FABER

Notă biografică

Orhan Pamuk, is the author of many celebrated books, including The White Castle, Istanbul and Snow. In 2003 he won the International IMPAC Award for My Name is Red, and in 2006 he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. The Museum of Innocence was an international bestseller, praised in the Guardian as 'an enthralling, immensely enjoyable piece of storytelling.' Orhan Pamuk lives in Istanbul.

Descriere

Like the Dublin of Joyce and Jan Morris' Venice, Orhan Pamuk's bestselling Istanbul: Memories of a City is a triumphant encounter of place and sensibility, beautifully written and immensely moving. Since the publication of Istanbul, Pamuk has continued to add to his collection of photographs of Istanbul.

Extras

Chapter One

Another Orhan

From a very young age, I suspected there was more to my world than I could see: Somewhere in the streets of Istanbul, in a house resembling ours, there lived another Orhan so much like me that he could pass for my twin, even my double. I can’t remember where I got this idea or how it came to me. It must have emerged from a web of rumors, misunderstandings, illusions, and fears. But in one of my earliest memories, it is already clear how I’ve come to feel about my ghostly other.

When I was five I was sent to live for a short time in another house. After one of their many stormy separations, my parents arranged to meet in Paris, and it was decided that my older brother and I should remain in Istanbul, though in separate places. My brother would stay in the heart of the family with our grandmother in the Pamuk Apartments, in Niflantaflý, but I would be sent to stay with my aunt in Cihangir. Hanging on the wall in this house–where I was treated with the utmost kindness–was a picture of a small child, and every once in a while my aunt or uncle would point up at him and say with a smile, “Look! That’s you!”

The sweet doe-eyed boy inside the small white frame did look a bit like me, it’s true. He was even wearing the cap I sometimes wore. I knew I was not that boy in the picture (a kitsch representation of a “cute child” that someone had brought back from Europe). And yet I kept asking myself, Is this the Orhan who lives in that other house?

Of course, now I too was living in another house. It was as if I’d had to move here before I could meet my twin, but as I wanted only to return to my real home, I took no pleasure in making his acquaintance. My aunt and uncle’s jovial little game of saying I was the boy in the picture became an unintended taunt, and each time I’d feel my mind unraveling: my ideas about myself and the boy who looked like me, my picture and the picture I resembled, my home and the other house–all would slide about in a confusion that made me long all the more to be at home again, surrounded by my family.

Soon my wish came true. But the ghost of the other Orhan in another house somewhere in Istanbul never left me. Throughout my childhood and well into adolescence, he haunted my thoughts. On winter evenings, walking through the streets of the city, I would gaze into other people’s houses through the pale orange light of home and dream of happy, peaceful families living comfortable lives. Then I would shudder to think that the other Orhan might be living in one of these houses. As I grew older, the ghost became a fantasy and the fantasy a recurrent nightmare. In some dreams I would greet this Orhan–always in another house–with shrieks of horror; in others the two of us would stare each other down in eerie merciless silence. Afterward, wafting in and out of sleep, I would cling ever more fiercely to my pillow, my house, my street, my place in the world. Whenever I was unhappy, I imagined going to the other house, the other life, the place where the other Orhan lived, and in spite of everything I’d half convince myself that I was he and took pleasure in imagining how happy he was, such pleasure that, for a time, I felt no need to go to seek out the other house in that other imagined part of the city.

Here we come to the heart of the matter: I’ve never left Istanbul, never left the houses, streets, and neighborhoods of my childhood. Although I’ve lived in different districts from time to time, fifty years on I find myself back in the Pamuk Apartments, where my first photographs were taken and where my mother first held me in her arms to show me the world. I know this persistence owes something to my imaginary friend, the other Orhan, and to the solace I took from the bond between us. But we live in an age defined by mass migration and creative immigrants, so I am sometimes hard-pressed to explain why I’ve stayed, not only in the same place but in the same building. My mother’s sorrowful voice comes back to me: “Why don’t you go outside for a while? Why don’t you try a change of scene, do some traveling . . . ?”

Conrad, Nabokov, Naipaul–these are writers known for having managed to migrate between languages, cultures, countries, continents, even civilizations. Their imaginations were fed by exile, a nourishment drawn not through roots but through rootlessness. My imagination, however, requires that I stay in the same city, on the same street, in the same house, gazing at the same view. Istanbul’s fate is my fate. I am attached to this city because it has made me who I am.

Gustave Flaubert, who visited Istanbul 102 years before my birth, was struck by the variety of life in its teeming streets; in one of his letters he predicted that in a century’s time it would be the capital of the world. The reverse came true: After the Ottoman Empire collapsed, the world almost forgot that Istanbul existed. The city into which I was born was poorer, shabbier, and more isolated than it had ever been before in its two-thousand-year history. For me it has always been a city of ruins and of end-of-empire melancholy. I’ve spent my life either battling with this melancholy or (like all ‹stanbullus) making it my own.

At least once in a lifetime, self-reflection leads us to examine the circumstances of our birth. Why were we born in this particular corner of the world, on this particular date? These families into which we were born, these countries and cities to which the lottery of life has assigned us–they expect love from us, and in the end we do love them from the bottom of our hearts; but did we perhaps deserve better? I sometimes think myself unlucky to have been born in an aging and impoverished city buried under the ashes of a ruined empire. But a voice inside me always insists this was really a piece of luck. If it is a matter of wealth, I can certainly count myself fortunate to have been born into an affluent family at a time when the city was at its lowest ebb (though some have ably argued the contrary). Mostly, I am disinclined to complain; I’ve accepted the city into which I was born in the same way that I’ve accepted my body (much as I would have preferred to be more handsome and better built) and my gender (even though I still ask myself, naïvely, whether I might been better off had I been born a woman). This is my fate, and there’s no sense arguing with it. This book is concerned with fate.

I was born in the middle of the night on June 7, 1952, in a small private hospital in Moda. Its corridors, I’m told, were peaceful that night, and so was the world. Aside from the Strambolini volcano’s having suddenly begun to spew flames and ash two days earlier, relatively little seems to have been happening on our planet. The newspapers were full of small news: a few stories about the Turkish troops fighting in Korea; a few rumors spread by Americans stoking fears that the North Koreans might be preparing to use biological weapons. In the hours before I was born, my mother had been avidly following a local story: Two days earlier, the caretakers and “heroic” residents of the Konya Student Center had seen a man in a terrifying mask trying to enter a house in Langa through the bathroom window; they’d chased him through the streets to a lumberyard, where, after cursing the police, the hardened criminal had committed suicide; a seller of dry goods identified the corpse as a gangster who the year before had entered his shop in broad daylight and robbed him at gunpoint.

When she was reading the latest on this drama, my mother was alone in her room, or so she told me with a mixture of regret and annoyance many years later. After taking her to the hospital, my father had grown restless and, when my mother’s labor failed to progress, he’d gone out to meet with friends. The only person with her in the delivery room was my aunt, who’d managed to climb over the hospital’s garden wall in the middle of the night. When my mother first set eyes on me, she found me thinner and more fragile than my brother had been.

I feel compelled to add or so I’ve been told. In Turkish we have a special tense that allows us to distinguish hearsay from what we’ve seen with our own eyes; when we are relating dreams, fairy tales, or past events we could not have witnessed, we use this tense. It is a useful distinction to make as we “remember” our earliest life experiences, our cradles, our baby carriages, our first steps, all as reported by our parents, stories to which we listen with the same rapt attention we might pay some brilliant tale of some other person. It’s a sensation as sweet as seeing ourselves in our dreams, but we pay a heavy price for it. Once imprinted in our minds, other people’s reports of what we’ve done end up mattering more than what we ourselves remember. And just as we learn about our lives from others, so too do we let others shape our understanding of the city in which we live.

At times when I accept as my own the stories I’ve heard about my city and myself, I’m tempted to say, “Once upon a time I used to paint. I hear I was born in Istanbul, and I understand that I was a somewhat curious child. Then, when I was twenty-two, I seem to have begun writing novels without knowing why.” I’d have liked to write my entire story this way–as if my life were something that happened to someone else, as if it were a dream in which I felt my voice fading and my will succumbing to enchantment. Beautiful though it is, I find the language of epic unconvincing, for I cannot accept that the myths we tell about our first lives prepare us for the brighter, more authentic second lives that are meant to begin when we awake. Because–for people like me, at least–that second life is none other than the book in your hand. So pay close attention, dear reader. Let me be straight with you, and in return let me ask for your compassion.

Chapter Two

The Photographs in the Dark Museum House

My mother, my father, my older brother, my grandmother, my uncles, and my aunts–we all lived on different floors of the same five-story apartment house. Until the year before I was born, the different branches of the family had (like so many large Ottoman families) lived together in a large stone mansion; in 1951 they rented it out to a private elementary school and built the modern structure I would know as home on the empty lot next door; on the facade, in keeping with the custom of the time, they proudly put up a plaque that said pamuk apt. We lived on the fourth floor, but I had the run of the entire building from the time I was old enough to climb off my mother’s lap and can recall that on each floor there was at least one piano. When my last bachelor uncle put his newspaper down long enough to get married, and his new wife moved into the first-floor apartment, from which she was to spend the next half century gazing out the window, she brought her piano with her. No one ever played, on this one or any of the others; this may be why they made me feel so sad.

But it wasn’t just the unplayed pianos; in each apartment there was also a locked glass cabinet displaying Chinese porcelains, teacups, silver sets, sugar bowls, snuffboxes, crystal glasses, rosewater pitchers, plates, and censers that no one ever touched, although among them I sometimes found hiding places for miniature cars. There were the unused desks inlaid with mother-of-pearl, the turban shelves on which there were no turbans, and the Japanese and Art Nouveau screens behind which nothing was hidden. There, in the library, gathering dust behind the glass, were my doctor uncle’s medical books; in the twenty years since he’d emigrated to America, no human hand had touched them. To my childish mind, these rooms were furnished not for the living but for the dead. (Every once in a while a coffee table or a carved chest would disappear from one sitting room only to appear in another sitting room on another floor.)

If she thought we weren’t sitting properly on her silver-threaded chairs, our grandmother would bring us to attention. “Sit up straight!” Sitting rooms were not meant to be places where you could lounge comfortably; they were little museums designed to demonstrate to a hypothetical visitor that the householders were westernized. A person who was not fasting during Ramadan would perhaps suffer fewer pangs of conscience among these glass cupboards and dead pianos than he might if he were still sitting cross-legged in a room full of cushions and divans. Although everyone knew it as freedom from the laws of Islam, no one was quite sure what else westernization was good for. So it was not just in the affluent homes of Istanbul that you saw sitting-room museums; over the next fifty years you could find these haphazard and gloomy (but sometimes also poetic) displays of western influence in sitting rooms all over Turkey; only with the arrival of television in the 1970s did they go out of fashion. Once people had discovered how pleasurable it was to sit together to watch the evening news, their sitting rooms changed from little museums to little cinemas–although you still hear of old families who put their televisions in their central hallways, locking up their museum sitting rooms and opening them only for holidays or special guests.

Because the traffic between floors was as incessant as it had been in the Ottoman mansion, doors in our modern apartment building were usually left open. Once my brother had started school, my mother would let me go upstairs alone, or else we would walk up together to visit my paternal grandmother in her bed. The tulle curtains in her sitting room were always closed, but it made little difference; the building next door was so close as to make the room very dark anyway, especially in the morning, so I’d sit on the large heavy carpets and invent a game to play on my own. Arranging the miniature cars that someone had brought me from Europe into an obsessively neat line, I would admit them one by one into my garage. Then, pretending the carpets were seas and the chairs and tables islands, I would catapult myself from one to the other without ever touching water (much as Calvino’s Baron spent his life jumping from tree to tree without ever touching ground). When I was tired of this airborne adventure or of riding the arms of the sofas like horses (a game that may have been inspired by memories of the horse-drawn carriages of Heybeliada), I had another game that I would continue to play as an adult whenever I got bored: I’d imagine that the place in which I was sitting (this bedroom, this sitting room, this classroom, this barracks, this hospital room, this government office) was really somewhere else; when I had exhausted the energy to daydream, I would take refuge in the photographs that sat on every table, desk, and wall.

Another Orhan

From a very young age, I suspected there was more to my world than I could see: Somewhere in the streets of Istanbul, in a house resembling ours, there lived another Orhan so much like me that he could pass for my twin, even my double. I can’t remember where I got this idea or how it came to me. It must have emerged from a web of rumors, misunderstandings, illusions, and fears. But in one of my earliest memories, it is already clear how I’ve come to feel about my ghostly other.

When I was five I was sent to live for a short time in another house. After one of their many stormy separations, my parents arranged to meet in Paris, and it was decided that my older brother and I should remain in Istanbul, though in separate places. My brother would stay in the heart of the family with our grandmother in the Pamuk Apartments, in Niflantaflý, but I would be sent to stay with my aunt in Cihangir. Hanging on the wall in this house–where I was treated with the utmost kindness–was a picture of a small child, and every once in a while my aunt or uncle would point up at him and say with a smile, “Look! That’s you!”

The sweet doe-eyed boy inside the small white frame did look a bit like me, it’s true. He was even wearing the cap I sometimes wore. I knew I was not that boy in the picture (a kitsch representation of a “cute child” that someone had brought back from Europe). And yet I kept asking myself, Is this the Orhan who lives in that other house?

Of course, now I too was living in another house. It was as if I’d had to move here before I could meet my twin, but as I wanted only to return to my real home, I took no pleasure in making his acquaintance. My aunt and uncle’s jovial little game of saying I was the boy in the picture became an unintended taunt, and each time I’d feel my mind unraveling: my ideas about myself and the boy who looked like me, my picture and the picture I resembled, my home and the other house–all would slide about in a confusion that made me long all the more to be at home again, surrounded by my family.

Soon my wish came true. But the ghost of the other Orhan in another house somewhere in Istanbul never left me. Throughout my childhood and well into adolescence, he haunted my thoughts. On winter evenings, walking through the streets of the city, I would gaze into other people’s houses through the pale orange light of home and dream of happy, peaceful families living comfortable lives. Then I would shudder to think that the other Orhan might be living in one of these houses. As I grew older, the ghost became a fantasy and the fantasy a recurrent nightmare. In some dreams I would greet this Orhan–always in another house–with shrieks of horror; in others the two of us would stare each other down in eerie merciless silence. Afterward, wafting in and out of sleep, I would cling ever more fiercely to my pillow, my house, my street, my place in the world. Whenever I was unhappy, I imagined going to the other house, the other life, the place where the other Orhan lived, and in spite of everything I’d half convince myself that I was he and took pleasure in imagining how happy he was, such pleasure that, for a time, I felt no need to go to seek out the other house in that other imagined part of the city.

Here we come to the heart of the matter: I’ve never left Istanbul, never left the houses, streets, and neighborhoods of my childhood. Although I’ve lived in different districts from time to time, fifty years on I find myself back in the Pamuk Apartments, where my first photographs were taken and where my mother first held me in her arms to show me the world. I know this persistence owes something to my imaginary friend, the other Orhan, and to the solace I took from the bond between us. But we live in an age defined by mass migration and creative immigrants, so I am sometimes hard-pressed to explain why I’ve stayed, not only in the same place but in the same building. My mother’s sorrowful voice comes back to me: “Why don’t you go outside for a while? Why don’t you try a change of scene, do some traveling . . . ?”

Conrad, Nabokov, Naipaul–these are writers known for having managed to migrate between languages, cultures, countries, continents, even civilizations. Their imaginations were fed by exile, a nourishment drawn not through roots but through rootlessness. My imagination, however, requires that I stay in the same city, on the same street, in the same house, gazing at the same view. Istanbul’s fate is my fate. I am attached to this city because it has made me who I am.

Gustave Flaubert, who visited Istanbul 102 years before my birth, was struck by the variety of life in its teeming streets; in one of his letters he predicted that in a century’s time it would be the capital of the world. The reverse came true: After the Ottoman Empire collapsed, the world almost forgot that Istanbul existed. The city into which I was born was poorer, shabbier, and more isolated than it had ever been before in its two-thousand-year history. For me it has always been a city of ruins and of end-of-empire melancholy. I’ve spent my life either battling with this melancholy or (like all ‹stanbullus) making it my own.

At least once in a lifetime, self-reflection leads us to examine the circumstances of our birth. Why were we born in this particular corner of the world, on this particular date? These families into which we were born, these countries and cities to which the lottery of life has assigned us–they expect love from us, and in the end we do love them from the bottom of our hearts; but did we perhaps deserve better? I sometimes think myself unlucky to have been born in an aging and impoverished city buried under the ashes of a ruined empire. But a voice inside me always insists this was really a piece of luck. If it is a matter of wealth, I can certainly count myself fortunate to have been born into an affluent family at a time when the city was at its lowest ebb (though some have ably argued the contrary). Mostly, I am disinclined to complain; I’ve accepted the city into which I was born in the same way that I’ve accepted my body (much as I would have preferred to be more handsome and better built) and my gender (even though I still ask myself, naïvely, whether I might been better off had I been born a woman). This is my fate, and there’s no sense arguing with it. This book is concerned with fate.

I was born in the middle of the night on June 7, 1952, in a small private hospital in Moda. Its corridors, I’m told, were peaceful that night, and so was the world. Aside from the Strambolini volcano’s having suddenly begun to spew flames and ash two days earlier, relatively little seems to have been happening on our planet. The newspapers were full of small news: a few stories about the Turkish troops fighting in Korea; a few rumors spread by Americans stoking fears that the North Koreans might be preparing to use biological weapons. In the hours before I was born, my mother had been avidly following a local story: Two days earlier, the caretakers and “heroic” residents of the Konya Student Center had seen a man in a terrifying mask trying to enter a house in Langa through the bathroom window; they’d chased him through the streets to a lumberyard, where, after cursing the police, the hardened criminal had committed suicide; a seller of dry goods identified the corpse as a gangster who the year before had entered his shop in broad daylight and robbed him at gunpoint.

When she was reading the latest on this drama, my mother was alone in her room, or so she told me with a mixture of regret and annoyance many years later. After taking her to the hospital, my father had grown restless and, when my mother’s labor failed to progress, he’d gone out to meet with friends. The only person with her in the delivery room was my aunt, who’d managed to climb over the hospital’s garden wall in the middle of the night. When my mother first set eyes on me, she found me thinner and more fragile than my brother had been.

I feel compelled to add or so I’ve been told. In Turkish we have a special tense that allows us to distinguish hearsay from what we’ve seen with our own eyes; when we are relating dreams, fairy tales, or past events we could not have witnessed, we use this tense. It is a useful distinction to make as we “remember” our earliest life experiences, our cradles, our baby carriages, our first steps, all as reported by our parents, stories to which we listen with the same rapt attention we might pay some brilliant tale of some other person. It’s a sensation as sweet as seeing ourselves in our dreams, but we pay a heavy price for it. Once imprinted in our minds, other people’s reports of what we’ve done end up mattering more than what we ourselves remember. And just as we learn about our lives from others, so too do we let others shape our understanding of the city in which we live.

At times when I accept as my own the stories I’ve heard about my city and myself, I’m tempted to say, “Once upon a time I used to paint. I hear I was born in Istanbul, and I understand that I was a somewhat curious child. Then, when I was twenty-two, I seem to have begun writing novels without knowing why.” I’d have liked to write my entire story this way–as if my life were something that happened to someone else, as if it were a dream in which I felt my voice fading and my will succumbing to enchantment. Beautiful though it is, I find the language of epic unconvincing, for I cannot accept that the myths we tell about our first lives prepare us for the brighter, more authentic second lives that are meant to begin when we awake. Because–for people like me, at least–that second life is none other than the book in your hand. So pay close attention, dear reader. Let me be straight with you, and in return let me ask for your compassion.

Chapter Two

The Photographs in the Dark Museum House

My mother, my father, my older brother, my grandmother, my uncles, and my aunts–we all lived on different floors of the same five-story apartment house. Until the year before I was born, the different branches of the family had (like so many large Ottoman families) lived together in a large stone mansion; in 1951 they rented it out to a private elementary school and built the modern structure I would know as home on the empty lot next door; on the facade, in keeping with the custom of the time, they proudly put up a plaque that said pamuk apt. We lived on the fourth floor, but I had the run of the entire building from the time I was old enough to climb off my mother’s lap and can recall that on each floor there was at least one piano. When my last bachelor uncle put his newspaper down long enough to get married, and his new wife moved into the first-floor apartment, from which she was to spend the next half century gazing out the window, she brought her piano with her. No one ever played, on this one or any of the others; this may be why they made me feel so sad.

But it wasn’t just the unplayed pianos; in each apartment there was also a locked glass cabinet displaying Chinese porcelains, teacups, silver sets, sugar bowls, snuffboxes, crystal glasses, rosewater pitchers, plates, and censers that no one ever touched, although among them I sometimes found hiding places for miniature cars. There were the unused desks inlaid with mother-of-pearl, the turban shelves on which there were no turbans, and the Japanese and Art Nouveau screens behind which nothing was hidden. There, in the library, gathering dust behind the glass, were my doctor uncle’s medical books; in the twenty years since he’d emigrated to America, no human hand had touched them. To my childish mind, these rooms were furnished not for the living but for the dead. (Every once in a while a coffee table or a carved chest would disappear from one sitting room only to appear in another sitting room on another floor.)

If she thought we weren’t sitting properly on her silver-threaded chairs, our grandmother would bring us to attention. “Sit up straight!” Sitting rooms were not meant to be places where you could lounge comfortably; they were little museums designed to demonstrate to a hypothetical visitor that the householders were westernized. A person who was not fasting during Ramadan would perhaps suffer fewer pangs of conscience among these glass cupboards and dead pianos than he might if he were still sitting cross-legged in a room full of cushions and divans. Although everyone knew it as freedom from the laws of Islam, no one was quite sure what else westernization was good for. So it was not just in the affluent homes of Istanbul that you saw sitting-room museums; over the next fifty years you could find these haphazard and gloomy (but sometimes also poetic) displays of western influence in sitting rooms all over Turkey; only with the arrival of television in the 1970s did they go out of fashion. Once people had discovered how pleasurable it was to sit together to watch the evening news, their sitting rooms changed from little museums to little cinemas–although you still hear of old families who put their televisions in their central hallways, locking up their museum sitting rooms and opening them only for holidays or special guests.

Because the traffic between floors was as incessant as it had been in the Ottoman mansion, doors in our modern apartment building were usually left open. Once my brother had started school, my mother would let me go upstairs alone, or else we would walk up together to visit my paternal grandmother in her bed. The tulle curtains in her sitting room were always closed, but it made little difference; the building next door was so close as to make the room very dark anyway, especially in the morning, so I’d sit on the large heavy carpets and invent a game to play on my own. Arranging the miniature cars that someone had brought me from Europe into an obsessively neat line, I would admit them one by one into my garage. Then, pretending the carpets were seas and the chairs and tables islands, I would catapult myself from one to the other without ever touching water (much as Calvino’s Baron spent his life jumping from tree to tree without ever touching ground). When I was tired of this airborne adventure or of riding the arms of the sofas like horses (a game that may have been inspired by memories of the horse-drawn carriages of Heybeliada), I had another game that I would continue to play as an adult whenever I got bored: I’d imagine that the place in which I was sitting (this bedroom, this sitting room, this classroom, this barracks, this hospital room, this government office) was really somewhere else; when I had exhausted the energy to daydream, I would take refuge in the photographs that sat on every table, desk, and wall.

Recenzii

Delightful, profound, marvelously original. . . . Pamuk tells the story of the city through the eyes of memory." –The Washington Post Book World"Far from a conventional appreciation of the city's natural and architectural splendors, Istanbul tells of an invisible melancholy and the way it acts on an imaginative young man, aggrieving him but pricking his creativity." –The New York Times"Brilliant. . . . Pamuk insistently discribes a]dizzingly gorgeous, historically vibrant metropolis." –Newsday “A fascinating read for anyone who has even the slightest acquaintance with this fabled bridge between east and west.” –The Economist