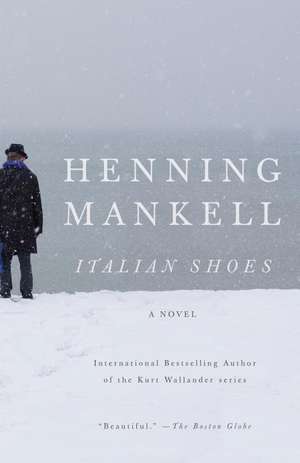

Italian Shoes

Autor Henning Mankell Traducere de Laurie Thompsonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 2010

Many years ago a devastating mistake drove Fredrik Welkin into a life as far as possible from his former position as a surgeon, where he mistakenly amputated the wrong arm of one of his patients. Now he lives in a frozen landscape. Each morning he dips his body into the freezing lake surrounding his home to remind himself he’s alive. However, Welkins’s icy existence begins to thaw when he receives a visit from a guest who helps him embark on a journey to acceptance and understanding. Full of the graceful prose and deft characterization that have been the hallmarks of Mankell’s prose, Italian Shoes shows a modern master at the height of his powers, effortlessly delivering a remarkable novel about the most rewarding theme of all: hope.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 54.25 lei 24-35 zile | +20.94 lei 4-10 zile |

| Vintage Publishing – apr 2010 | 54.25 lei 24-35 zile | +20.94 lei 4-10 zile |

| Vintage Books USA – 30 sep 2010 | 119.50 lei 17-23 zile | +10.35 lei 4-10 zile |

Preț: 119.50 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 179

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.87€ • 23.63$ • 19.03£

22.87€ • 23.63$ • 19.03£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 28 februarie-06 martie

Livrare express 15-21 februarie pentru 20.34 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307472243

ISBN-10: 0307472248

Pagini: 247

Dimensiuni: 135 x 201 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 0307472248

Pagini: 247

Dimensiuni: 135 x 201 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

Internationally acclaimed author Henning Mankell has written nine Kurt Wallander mysteries. The books have been published in thirty-three countries and consistently top the bestseller lists in Europe, receiving major literary prizes (including the UK's Golden Dagger for Sidetracked) and generating numerous international film and television adaptations. He has also published many other novels for children, teens, and adults. In addition, he is one of Sweden's most popular dramatists.

Born in 1948, Mankell grew up in the Swedish village Sveg. He now divides his time between Sweden and Maputo, Mozambique, where he works as a director at Teatro Avenida. He has spent many years in Africa, where a number of his novels are set.

Born in 1948, Mankell grew up in the Swedish village Sveg. He now divides his time between Sweden and Maputo, Mozambique, where he works as a director at Teatro Avenida. He has spent many years in Africa, where a number of his novels are set.

Extras

Chapter 1

I always feel more lonely when it's cold.

The cold outside my window reminds me of the cold emanating from my own body. I'm being attacked from two directions. But I'm constantly resisting. That's why I cut a hole in the ice every morning. If anyone were to stand with a telescope on the ice in the frozen bay and saw what I was doing, he would think that I was crazy and was about to arrange my own death. A naked man in the freezing cold, with an axe in his hand, opening up a hole in the ice?

I suppose, really, that I hope there will be somebody out there one of these days, a black shadow against all the white — somebody who sees me and wonders if he'd be able to stop me before it was too late. But it's not necessary to stop me because I have no intention of committing suicide.

Earlier in my life, in connection with the big catastrophe, my fury and despair were sometimes so overwhelming that I did consider doing away with myself. But I never actually tried. Cowardice has been a faithful companion throughout my life. Like now, I thought then that life is all about never losing your grip. Life is a flimsy branch over an abyss. I'm hanging on to it for as long as I have the strength. Eventually I shall fall, like everybody else, and I don't know what will lie in store. Is there somebody down there to catch me? Or will there be nothing but cold, harsh blackness rushing towards me?

The ice is here to stay.

It's a hard winter this year, at the beginning of the new millennium. This morning, when I woke up in the December darkness, I thought I could hear the ice singing. I don't know where I've got the idea from that ice can sing. Perhaps my grandfather, who was born here on this little island, told me about it when I was a small boy.

But I was woken up this morning, while it was still dark, by a sound. It wasn't the cat or the dog. I have two pets who sleep more soundly than I do. My cat is old and stiff, and my dog is stone deaf in his right ear and can't hear much in his left. I can creep past him without him knowing.

But that noise?

I tried to get my bearings in the darkness. It was some time before I realised it must be the ice moving, although it's a foot or more deep here in the bay. Last week, one day when I was more troubled than usual, I walked out towards the edge of the ice, where it meets the open sea, now stretching for a mile beyond the outermost skerry. That means that the ice here in the bay ought not to have been moving at all. But, in fact, it was rising and falling, creaking and singing.

I listen to this sound, and it occurred to me that my life has passed very fast. Now I'm here. A man aged sixty-six, financially independent, burdened with a memory that plagues me constantly. I grew up in desperate circumstances that are impossible to imagine nowadays in Sweden. My father was a browbeaten and overweight waiter, and my mother spent all her time trying to make ends meet. I succeeded in clambering out of that pit of poverty. As a child, I used to play out here in the archipelago every summer, and had no concept of time passing. In those days my grandfather and grandmother were still active, they hadn't yet aged to a point where they were unable to move and merely waited for death. He smelled of fish, and she had no teeth left. Although she was always kind to me, there was something frightening about her smile, the way her mouth opened to reveal a black hole.

It seems not so long ago since I was in the first act. Now the epilogue has already started.

The ice was singing out there in the darkness, and I wondered if I was about to suffer a heart attack. I got up and took my blood pressure. There was nothing wrong with me, the reading was 155/90, my pulse was normal at 64 beats per minute. I felt to see if I had pain anywhere. My left leg ached slightly, but it always does and it's not something I worry about. But the sound of the ice out there was influencing my mood. Like an eerie choir made up of strange voices. I sat down in the kitchen and waited for dawn. The timbers of the cottage were creaking and squeaking. Either the cold was causing the timber to contract, or perhaps a mouse was scurrying along one of its secret passages.

***

The thermometer attached to the outside of the kitchen window indicated minus nineteen degrees Celsius.

I decide that today I shall do exactly what I do every other winter day. I put on my dressing gown, thrust my feet into a pair of cut-down wellington boots, collect my axe and walk down to the jetty. It doesn't take long to open up my hole in the ice — the area I usually chip away hasn't had time to freeze hard again. Then I undress and jump into the slushy water. It hurts, but when I clamber out, it feels as if the cold has been transformed into intensive heat.

Every day I jump down into my black hole in order to get the feeling that I'm still alive. Afterwards, it's as if my loneliness slowly fades away. One day, perhaps, I shall die of the shock from plunging into freezing cold water. As my feet reach the bottom I can stand up in the water; I shan't disappear under the ice. I shall remain standing there as the ice quickly freezes up again. That's where Jansson, the man who delivers post to the islands of the archipelago, will find me.

No matter how long he lives, he will never understand what happened.

But I don't worry about that. I've arranged my home out here on the little island I inherited as an impregnable fortress. When I climb the hill behind my house, I can see the more substantial and less hospitable islands of the inner archipelago. But nowhere is there any other dwelling to be seen.

Needless to say, this isn't how I envisaged it.

This house was going to be my summer cottage. Not my final redoubt. Every morning, when I've cut my hole in the ice or lowered myself down into the warm waters of summer, I am again amazed by what has happened to my life.

I made a mistake. And I refused to accept the consequences. If I'd known then what I know now, what would I have done? I'm not sure. But I know I wouldn't have needed to spend my life out here like a prisoner, on a deserted island at the edge of the open sea.

I should have followed my plan.

I made up my mind to become a doctor on my fifteenth birthday. To my amazement my father had taken me out for a meal. He worked as a waiter, but in a stubborn attempt to preserve his dignity he worked only during the day, never in the evening. If he was instructed to work evenings, he would resign. I can still recall my mother's tears when he come home and announced that he had resigned again. But now, out of the blue, he was going to take me to a restaurant for a meal. I had heard my parents quarrelling about whether or not I should be given this 'present', and it ended with my mother locking herself away in the bedroom. That was normal when something went against her wishes. Those were especially difficult periods when she spent most of her time locked away in the bedroom. The room always smelled of lavender and tears. I always slept on the kitchen sofa, and my father would sigh deeply as he made his bed on a mattress on the floor.

In my life I have come across many people who weep. During my years as a doctor, I frequently met people who were dying, and others who had been forced to accept that a loved one was dying. But their tears never emitted a perfume reminiscent of my mother's. On the way to the restaurant, my father explained to me that she was oversensitive. I still can't recall what my response was. What could I say? My earliest memories are of my mother crying hour after hour lamenting the shortage of money, the poverty that undermined our lives. My father didn't seem to hear her weeping. If she was in a good mood when he came home, all was well. If she was in bed, surrounded by the scent of lavender, that was also good. My father used to devote his evenings to sorting out his large collection of tin soldiers, and reconstructing famous battles. Before I fell asleep, he would often lie down beside my bed, stroke my head, and express his regret at the fact that my mother was so sensitive that, unfortunately, it was not possible to present me with any brothers or sisters.

I grew up in a no-man's-land between tears and tin soldiers. And with a father who insisted that, as with an opera singer, a waiter required decent shoes if he was to be able to do his job properly.

It turned out in accordance with his wish. We went to the restaurant. A waiter came to take our order. My father asked all kinds of complicated and detailed questions about the veal he eventually ordered. I had plumped for herring. My summers spent in the archipelago had taught me to appreciate fish. The waiter left us in peace.

This was the first time I had ever drunk a glass of wine. I was intoxicated almost with the first sip. After the meal, my father smiled and asked me what career I intended to take up.

I didn't know. He'd invested a lot of money enabling me to stay on at school. The depressing atmosphere and shabbily dressed teachers patrolling the evil-smelling corridors had not inspired me to think about the future. It was a matter of surviving from day to day, preferably avoiding being exposed as one of those who hadn't done their homework, and not collecting a black mark. Each day was always very pressing, and it was impossible to envisage a horizon beyond the end of term. Even today, I can't remember a single occasion when I spoke to my classmates about the future.

'You're fifteen now,' my father said. 'It's time for you to think about what you're going to do in life. Are you interested in the culinary trade? When you've passed your exams you could earn enough washing dishes to fund a passage to America. It's a good idea to see the world. Just make sure that you have a decent pair of shoes.'

'I don't want to be a waiter.'

I was very firm about that. I wasn't sure if my father was disappointed or relieved. He took a sip of wine, stroked his nose, then asked if I had any definite plans for my life.

'No.'

'But you must have had a thought or two. What's your favorite subject?'

'Music.'

'Can you sing? That would be news to me.'

'No, I can't sing.'

'Have you learned to play an instrument, without my knowing?'

'No.'

'Then why do you like music best?'

'Because Ramberg, the music teacher, pays no attention to me.'

'What do you mean by that?'

'He's only interested in pupils who can sing. He doesn't know the rest of us are there.'

'So your favorite subject is the one that you don't really attend, is that it?'

'Chemistry's good as well.'

My father was obviously surprised by this. For a brief moment he seemed to be searching through his memory for his own inadequate schooldays, and wondering if there had even been a subject called chemistry. As I looked at him, he seemed bewitched. He was transformed before my very eyes. Until now the only things about him that had changed over the years were his clothes, his shoes and the colour of his hair (which had become greyer and greyer). But now something unexpected was happening. He seemed to be afflicted by a sort of helplessness that I'd never noticed before. Although he'd often sat on the edge of my bed or swum with me out here in the bay, he was always distant. Now, when he was exhibiting his helplessness, he seemed to come much closer to me. I was stronger than the man sitting opposite me, on the other side of the white tablecloth, in a restaurant where an ensemble was playing music that nobody listened to, where cigarette smoke mixed with pungent perfumes, and the wine was ebbing away from his glass.

That was when I made up my mind what I would say. That was the very moment at which I discovered, or perhaps devised, my future. My father fixed me with his greyish-blue eyes. He seemed to have recovered from the feeling of helplessness that had overcome him. But I had seen it, and would never forget it.

'You say you think that chemistry is good. Why?'

'Because I'm going to be a doctor. So you have to know a bit about chemical substances. I want to do operations.'

He looked at me with obvious disgust.

'You mean you want to cut people up?'

'Yes.'

'But you can't be a doctor unless you stay on at school longer.'

'That's what I intend on doing.'

'So that you can poke your fingers around people's insides?'

'I want to be a surgeon.'

I'd never thought about the possibility of becoming a doctor. I didn't faint at the sight of blood, or when I had an injection; but I'd never thought about life in hospital wards and operating theatres. As we walked home that April evening, my father a bit tipsy and me a fifteen-year-old suffering from his first taste of wine, I realised that I hadn't only answered my father's questions. I'd given myself something to live up to.

I was going to become a doctor. I was going to spend my life cutting into people's bodies.

I always feel more lonely when it's cold.

The cold outside my window reminds me of the cold emanating from my own body. I'm being attacked from two directions. But I'm constantly resisting. That's why I cut a hole in the ice every morning. If anyone were to stand with a telescope on the ice in the frozen bay and saw what I was doing, he would think that I was crazy and was about to arrange my own death. A naked man in the freezing cold, with an axe in his hand, opening up a hole in the ice?

I suppose, really, that I hope there will be somebody out there one of these days, a black shadow against all the white — somebody who sees me and wonders if he'd be able to stop me before it was too late. But it's not necessary to stop me because I have no intention of committing suicide.

Earlier in my life, in connection with the big catastrophe, my fury and despair were sometimes so overwhelming that I did consider doing away with myself. But I never actually tried. Cowardice has been a faithful companion throughout my life. Like now, I thought then that life is all about never losing your grip. Life is a flimsy branch over an abyss. I'm hanging on to it for as long as I have the strength. Eventually I shall fall, like everybody else, and I don't know what will lie in store. Is there somebody down there to catch me? Or will there be nothing but cold, harsh blackness rushing towards me?

The ice is here to stay.

It's a hard winter this year, at the beginning of the new millennium. This morning, when I woke up in the December darkness, I thought I could hear the ice singing. I don't know where I've got the idea from that ice can sing. Perhaps my grandfather, who was born here on this little island, told me about it when I was a small boy.

But I was woken up this morning, while it was still dark, by a sound. It wasn't the cat or the dog. I have two pets who sleep more soundly than I do. My cat is old and stiff, and my dog is stone deaf in his right ear and can't hear much in his left. I can creep past him without him knowing.

But that noise?

I tried to get my bearings in the darkness. It was some time before I realised it must be the ice moving, although it's a foot or more deep here in the bay. Last week, one day when I was more troubled than usual, I walked out towards the edge of the ice, where it meets the open sea, now stretching for a mile beyond the outermost skerry. That means that the ice here in the bay ought not to have been moving at all. But, in fact, it was rising and falling, creaking and singing.

I listen to this sound, and it occurred to me that my life has passed very fast. Now I'm here. A man aged sixty-six, financially independent, burdened with a memory that plagues me constantly. I grew up in desperate circumstances that are impossible to imagine nowadays in Sweden. My father was a browbeaten and overweight waiter, and my mother spent all her time trying to make ends meet. I succeeded in clambering out of that pit of poverty. As a child, I used to play out here in the archipelago every summer, and had no concept of time passing. In those days my grandfather and grandmother were still active, they hadn't yet aged to a point where they were unable to move and merely waited for death. He smelled of fish, and she had no teeth left. Although she was always kind to me, there was something frightening about her smile, the way her mouth opened to reveal a black hole.

It seems not so long ago since I was in the first act. Now the epilogue has already started.

The ice was singing out there in the darkness, and I wondered if I was about to suffer a heart attack. I got up and took my blood pressure. There was nothing wrong with me, the reading was 155/90, my pulse was normal at 64 beats per minute. I felt to see if I had pain anywhere. My left leg ached slightly, but it always does and it's not something I worry about. But the sound of the ice out there was influencing my mood. Like an eerie choir made up of strange voices. I sat down in the kitchen and waited for dawn. The timbers of the cottage were creaking and squeaking. Either the cold was causing the timber to contract, or perhaps a mouse was scurrying along one of its secret passages.

***

The thermometer attached to the outside of the kitchen window indicated minus nineteen degrees Celsius.

I decide that today I shall do exactly what I do every other winter day. I put on my dressing gown, thrust my feet into a pair of cut-down wellington boots, collect my axe and walk down to the jetty. It doesn't take long to open up my hole in the ice — the area I usually chip away hasn't had time to freeze hard again. Then I undress and jump into the slushy water. It hurts, but when I clamber out, it feels as if the cold has been transformed into intensive heat.

Every day I jump down into my black hole in order to get the feeling that I'm still alive. Afterwards, it's as if my loneliness slowly fades away. One day, perhaps, I shall die of the shock from plunging into freezing cold water. As my feet reach the bottom I can stand up in the water; I shan't disappear under the ice. I shall remain standing there as the ice quickly freezes up again. That's where Jansson, the man who delivers post to the islands of the archipelago, will find me.

No matter how long he lives, he will never understand what happened.

But I don't worry about that. I've arranged my home out here on the little island I inherited as an impregnable fortress. When I climb the hill behind my house, I can see the more substantial and less hospitable islands of the inner archipelago. But nowhere is there any other dwelling to be seen.

Needless to say, this isn't how I envisaged it.

This house was going to be my summer cottage. Not my final redoubt. Every morning, when I've cut my hole in the ice or lowered myself down into the warm waters of summer, I am again amazed by what has happened to my life.

I made a mistake. And I refused to accept the consequences. If I'd known then what I know now, what would I have done? I'm not sure. But I know I wouldn't have needed to spend my life out here like a prisoner, on a deserted island at the edge of the open sea.

I should have followed my plan.

I made up my mind to become a doctor on my fifteenth birthday. To my amazement my father had taken me out for a meal. He worked as a waiter, but in a stubborn attempt to preserve his dignity he worked only during the day, never in the evening. If he was instructed to work evenings, he would resign. I can still recall my mother's tears when he come home and announced that he had resigned again. But now, out of the blue, he was going to take me to a restaurant for a meal. I had heard my parents quarrelling about whether or not I should be given this 'present', and it ended with my mother locking herself away in the bedroom. That was normal when something went against her wishes. Those were especially difficult periods when she spent most of her time locked away in the bedroom. The room always smelled of lavender and tears. I always slept on the kitchen sofa, and my father would sigh deeply as he made his bed on a mattress on the floor.

In my life I have come across many people who weep. During my years as a doctor, I frequently met people who were dying, and others who had been forced to accept that a loved one was dying. But their tears never emitted a perfume reminiscent of my mother's. On the way to the restaurant, my father explained to me that she was oversensitive. I still can't recall what my response was. What could I say? My earliest memories are of my mother crying hour after hour lamenting the shortage of money, the poverty that undermined our lives. My father didn't seem to hear her weeping. If she was in a good mood when he came home, all was well. If she was in bed, surrounded by the scent of lavender, that was also good. My father used to devote his evenings to sorting out his large collection of tin soldiers, and reconstructing famous battles. Before I fell asleep, he would often lie down beside my bed, stroke my head, and express his regret at the fact that my mother was so sensitive that, unfortunately, it was not possible to present me with any brothers or sisters.

I grew up in a no-man's-land between tears and tin soldiers. And with a father who insisted that, as with an opera singer, a waiter required decent shoes if he was to be able to do his job properly.

It turned out in accordance with his wish. We went to the restaurant. A waiter came to take our order. My father asked all kinds of complicated and detailed questions about the veal he eventually ordered. I had plumped for herring. My summers spent in the archipelago had taught me to appreciate fish. The waiter left us in peace.

This was the first time I had ever drunk a glass of wine. I was intoxicated almost with the first sip. After the meal, my father smiled and asked me what career I intended to take up.

I didn't know. He'd invested a lot of money enabling me to stay on at school. The depressing atmosphere and shabbily dressed teachers patrolling the evil-smelling corridors had not inspired me to think about the future. It was a matter of surviving from day to day, preferably avoiding being exposed as one of those who hadn't done their homework, and not collecting a black mark. Each day was always very pressing, and it was impossible to envisage a horizon beyond the end of term. Even today, I can't remember a single occasion when I spoke to my classmates about the future.

'You're fifteen now,' my father said. 'It's time for you to think about what you're going to do in life. Are you interested in the culinary trade? When you've passed your exams you could earn enough washing dishes to fund a passage to America. It's a good idea to see the world. Just make sure that you have a decent pair of shoes.'

'I don't want to be a waiter.'

I was very firm about that. I wasn't sure if my father was disappointed or relieved. He took a sip of wine, stroked his nose, then asked if I had any definite plans for my life.

'No.'

'But you must have had a thought or two. What's your favorite subject?'

'Music.'

'Can you sing? That would be news to me.'

'No, I can't sing.'

'Have you learned to play an instrument, without my knowing?'

'No.'

'Then why do you like music best?'

'Because Ramberg, the music teacher, pays no attention to me.'

'What do you mean by that?'

'He's only interested in pupils who can sing. He doesn't know the rest of us are there.'

'So your favorite subject is the one that you don't really attend, is that it?'

'Chemistry's good as well.'

My father was obviously surprised by this. For a brief moment he seemed to be searching through his memory for his own inadequate schooldays, and wondering if there had even been a subject called chemistry. As I looked at him, he seemed bewitched. He was transformed before my very eyes. Until now the only things about him that had changed over the years were his clothes, his shoes and the colour of his hair (which had become greyer and greyer). But now something unexpected was happening. He seemed to be afflicted by a sort of helplessness that I'd never noticed before. Although he'd often sat on the edge of my bed or swum with me out here in the bay, he was always distant. Now, when he was exhibiting his helplessness, he seemed to come much closer to me. I was stronger than the man sitting opposite me, on the other side of the white tablecloth, in a restaurant where an ensemble was playing music that nobody listened to, where cigarette smoke mixed with pungent perfumes, and the wine was ebbing away from his glass.

That was when I made up my mind what I would say. That was the very moment at which I discovered, or perhaps devised, my future. My father fixed me with his greyish-blue eyes. He seemed to have recovered from the feeling of helplessness that had overcome him. But I had seen it, and would never forget it.

'You say you think that chemistry is good. Why?'

'Because I'm going to be a doctor. So you have to know a bit about chemical substances. I want to do operations.'

He looked at me with obvious disgust.

'You mean you want to cut people up?'

'Yes.'

'But you can't be a doctor unless you stay on at school longer.'

'That's what I intend on doing.'

'So that you can poke your fingers around people's insides?'

'I want to be a surgeon.'

I'd never thought about the possibility of becoming a doctor. I didn't faint at the sight of blood, or when I had an injection; but I'd never thought about life in hospital wards and operating theatres. As we walked home that April evening, my father a bit tipsy and me a fifteen-year-old suffering from his first taste of wine, I realised that I hadn't only answered my father's questions. I'd given myself something to live up to.

I was going to become a doctor. I was going to spend my life cutting into people's bodies.

Recenzii

“Beautiful.”—The Boston Globe

"A voyage into the soul of a man."--The Guardian, London

“A fine meditation on love and loss.”--Sunday Telegraph, London

“Intense and precisely detailed. . . . A hopeful account of a man released from self-imposed withdrawal.”—The Independent, London

"A voyage into the soul of a man."--The Guardian, London

“A fine meditation on love and loss.”--Sunday Telegraph, London

“Intense and precisely detailed. . . . A hopeful account of a man released from self-imposed withdrawal.”—The Independent, London

Descriere

From the prizewinning master of atmosphere ("The Boston Globe") and the creator of the bestselling Kurt Wallender mystery series comes the surprising and affecting story of a man well past middle age who suddenly finds himself on the threshold of renewal.