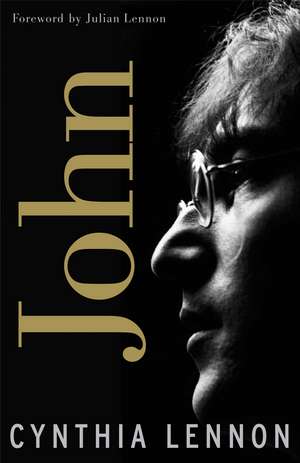

John

Autor Cynthia Lennon Julian Lennonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2006

The time has come when I feel ready to tell the truth about John and me, our years together and the years since his death. There is so much that I have never said, so many incidents I have never spoken of and so many feelings I have never expressed: great love on one hand; pain, torment, and humiliation on the other. Only I know what really happened between us, why we stayed together, why we parted, and the price I have paid for being John’s wife. —From the Introduction

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 54.62 lei 3-5 săpt. | +28.93 lei 6-10 zile |

| Hodder & Stoughton – 10 apr 2006 | 54.62 lei 3-5 săpt. | +28.93 lei 6-10 zile |

| Three Rivers Press (CA) – 31 iul 2006 | 93.82 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 93.82 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 141

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.95€ • 19.50$ • 15.08£

17.95€ • 19.50$ • 15.08£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 02-16 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307338563

ISBN-10: 0307338568

Pagini: 306

Ilustrații: 2 16-PG B&W PHOTO INSERTS

Dimensiuni: 135 x 203 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

ISBN-10: 0307338568

Pagini: 306

Ilustrații: 2 16-PG B&W PHOTO INSERTS

Dimensiuni: 135 x 203 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

Notă biografică

Cynthia Lennon was born in Blackpool, England, in 1939. While attending the Liverpool College of Art she met John Lennon. John and Cynthia married in 1962 and their son, Julian, was born in 1963. The Lennons were divorced in 1969. Cynthia retained custody of Julian, who saw his father sporadically until John was killed in 1980. In the years since, Cynthia has been a restaurateur, a designer, and a television personality. She now lives in Spain with her husband, Noel Charles.

Extras

Chapter 1

One early December afternoon in 1980 my friend Angie and I were in the little bistro we ran in north Wales, putting up the Christmas decorations. It was a cold, dark afternoon, but the atmosphere inside was bright and warm. We'd opened a bottle of wine and were hanging baubles on the tree and festive pictures on the walls. Laughing, we pulled a cracker and the toy inside fell onto the floor. I bent to pick it up and shivered when I saw it was a small plastic gun. It seemed horribly out of place among the tinsel and paper chains.

The next day I went to stay with my friend Mo Starkey in London. I couldn't really spare the time during the busy pre-Christmas season, but my lawyer had insisted I go to sign some legal papers, so I took the train, planning to return the following day. I left my husband and Angie to look after things in my absence. Angie was the ex-wife of Paul McCartney's brother, Mike, and after her marriage broke up she'd come to work for us, living in the small flat above the bistro.

It was always good to see Mo. We'd been friends since 1962, when I was John's girlfriend and she was the teenage fan who fell in love with Ringo at the Cavern. Ringo and Mo had married eighteen months after us, and in the days when the Beatles were traveling all over the world, she and I had spent a lot of time together. Her oldest son, Zak, was fifteen, a year and a half younger than my son Julian, and the boys had always been playmates.

When Mo and Ringo parted in 1974 she had been so heartbroken that she got on a motorbike and drove it straight into a brick wall, badly injuring herself. She had been in love with him since she was fifteen and his public appearances with his new girlfriend, American actress Nancy Andrews, had devastated her.

After the split Mo, still only twenty-seven, had moved into a house in the London neighborhood Maida Vale with her three children, Zak, eight, Jason, six, and Lee, three. Because of the injuries she'd received in the motorbike accident she had plastic surgery on her face and was delighted with the result, which she felt made her look better than she had before. Gradually she'd begun to get over Ringo, and she had a brief fling with George Harrison before she began to see Isaac Tigrett, millionaire owner of the Hard Rock Café chain.

The evening I arrived Mo had her usual houseful of people. Her mother, Flo, lived with her, as well as the children and their nanny. Mo always had an open house and that evening some old friends of ours, Jill and Dale Newton, had joined us for dinner. The nanny had cooked a huge meal, and later, Jill and Dale, Maureen and I sat over a couple of bottles of wine and talked about old times. After a while the conversation turned to the death of Mal Evans, the Beatles' former road manager. Mal had been a giant of a man, generous and soft-hearted. We'd known him since the early days when he'd worked for the post office and moonlighted as a bouncer at the Cavern Club. When the Beatles began to be successful they took him on to work for them.

Mal had been a faithful friend to the boys and was especially close to John: they got on incredibly well and, with the Beatles' other loyal roadie, Neil Aspinall, he had been on every tour, organizing, trouble-shooting, protecting and looking after them.

When the Beatles broke up Mal had been lost. He'd gone to live in Los Angeles where he began drinking and taking drugs. It was there, on January 4, 1976, that the police had been called by his girlfriend during a row. She claimed that Mal had pulled a gun on her, and when they burst into the apartment the officers found Mal holding a gun. Apparently he pointed it at them before they shot him. It was only after he died that they found the gun wasn't loaded. It was a tragic story, and we could only imagine that Mal had been under the influence of drugs. The Mal we knew could no more have shot someone than flown to the moon. Whatever the true story, his death had shocked us all and that night, our talk around Mo's fireplace was of what a good man he had been and how awful his premature death was. To us, the idea of being shot was almost unimaginable-how could it have happened to such a good friend?

After a while I went to bed. I knew the others would carry on talking and drinking until the early hours, but I wanted a good night's sleep as I had to get up early in the morning to catch the train home.

I was asleep in the spare room when screams woke me. It took me a few seconds to realize that they were Mo's. At that moment she burst into my room: "Cyn, John's been shot. Ringo's on the phone-he wants to talk to you."

I don't remember getting out of bed and going down the stairs to the phone. But Ringo's words, the sound of his tearful voice crackling over the transatlantic line, was crystal clear: "Cyn, I'm so sorry, John's dead."

The shock engulfed me like a wave. I heard a raw, tearing sob and, with that strange detachment that sudden shock can trigger, realized I was making the noise. Mo took the phone, said good-bye to Ringo, then put her arms around me. "I'm so sorry, Cyn," she sobbed.

In my stunned state I had only one clear thought. My son-our son-was at home in bed: I had to get back so that I could tell him about his father's death. He was seventeen and history was repeating itself in a hideous way: both John and I had lost a parent at that age.

I rang my husband and told him I was on the way and not to tell Julian what had happened. My marriage-the third-had been strained for some time and, in my heart of hearts, I knew it was going to end, but he was supportive. "Of course," he said. "I'll do my best to keep it from him." By the time I was dressed and had gathered my things, Mo had organized a car and a driver to take me to Wales. She insisted on coming too, with Zak. "I'll bring Julian back to stay with us if he needs to get away from the press," she promised.

John had been shot in New York at 10:50 p.m. on December 8. The time difference meant it was 3:50 a.m. on December 9 in Britain. Ringo had rung us barely two hours after it had happened, and we were on the road by seven. It was a four-hour drive to north Wales, and during the journey I stared out of the window in the gray dawn and thought of John.

In the jumble of thoughts whirring around my mind two kept recurring. The first was that nine had always been a significant number for John. He was born on October 9 and so was his second son, Sean. His mother had lived at number 9; when we met my house number had been 18 (the two digits of which add up to 9) and the hospital address Julian was born in was number 126 (again, each digit adds up to 9). Brian Epstein had first heard the Beatles play on the ninth of the month, they had got their first record contract on the ninth and John had met Yoko on the ninth. The number had cropped up in John's life in numerous other ways, so much so that he wrote three songs around it-"One After 909," "Revolution 9" and "#9 Dream." Now he had died on the ninth-an astonishing coincidence by any reckoning.

My second thought was that for the past fourteen years John had lived with the fear that he would be shot. In 1966 he'd received a letter from a psychic, warning that he would be shot while he was in the States. We were both upset by that: the Beatles were about to do their last tour of the States and, of course, we thought the warning referred to that trip. He had just made his infamous remark about the Beatles being more popular than Christ and the world was in an uproar about it-crank letters and warnings arrived by every post. But that one had stuck in his mind.

Afraid as he was, he went on the tour, and apologized reluctantly for the remark. When he got home in one piece we were both relieved. But the psychic's warning remained in his mind and from then on it seemed that he was looking over his shoulder, waiting for the gunman to appear. He often used to say, "I'll be shot one day." Now, unbelievably, tragically, he had been.

We reached Ruthin by mid-morning, and as we rounded the corner into what was normally a sleepy little town, my heart sank. There was no way that my husband could have kept the news from Julian: the town was packed with press. Dozens of photographers and reporters filled the square, the streets to our house and the bistro.

Amazingly we managed to park a few streets away and slip in through the back door, without being spotted by the crowd at the front. Inside my husband was pacing up and down restlessly. My mother, who lived above the bistro with Angie, was peering anxiously at the crowd from behind a drawn curtain. She was seventy-seven and suffering from the early stages of Alzheimer's. Confused by the crowds outside, she had no idea what was going on.

I looked at my husband, the question unspoken. Did Julian know? He nodded toward the stairs. A minute later Julian came running down. I held out my arms to him. He came over to me and his lanky teenage frame crumpled into my lap. He wrapped his arms around my neck and sobbed onto my shoulder. I hugged him and we cried together, both heartbroken at the awful, pointless waste that his father's death represented.

Mo had busied herself making tea, while Zak sat quietly nearby, not knowing what to say or do. While we drank the tea we talked about what to do. Maureen offered to take Julian back to London, but he said, "I want to go to New York, Mum. I want to be where Dad was." Although the idea alarmed me, I understood.

Maureen and Zak hugged us and left, then Julian and I went up to the bedroom to ring Yoko. We were put straight through to her, and she agreed that she would like Julian to join her. She said she would organize a flight for him that afternoon. I told her I was worried about the state he was in, but Yoko made it clear that I was not

welcome. "It's not as though you're an old schoolfriend of mine, Cynthia." It was blunt, but I accepted it: there is no place for an ex-wife in public grieving.

A couple of hours later my husband and I drove Julian to Manchester airport. The press spotted us as we left home, but when they saw our faces they drew back and let us pass. I was grateful. We sat through the two-hour drive in virtual silence. I was exhausted by the depth of my emotions and by the need to hold back my pain and attend to the necessary practicalities, for Julian's sake.

At the airport I watched him being led off by a flight attendant, his shoulders bowed, his face chalk white. I knew he would sit on the plane surrounded by people reading newspapers with headlines about his father's death splashed across their front pages and I longed to run after him. Before he disappeared through the gate he turned back and waved. He looked painfully young and I ached at having to let him go.

Back in Wales the press was still camped outside our door in huge numbers-there wasn't a spare room left in town. Years later, when she was hosting the British talk show This Morning, Judy Finnegan told me that she had been a young reporter among that throng. "I felt for you," she told me. "You looked absolutely shattered."

I was furious when my husband let one of the more persuasive journalists, a man who said he was writing a book about John, into our home. Later he claimed that I gave him a lengthy interview, but in fact I said just a few words, then asked him to leave. I was in no state and no mood to give an interview. I fell into bed and lay, numb and exhausted, too wrung out for any more tears, trying to take in the enormity of what had happened.

That night, after I drifted into a shallow sleep, there was a terrible crash. I leapt up, screaming-it was as though a bomb had gone off. I ran outside in my nightdress and saw that the chimney pot on our roof had crashed through the ceiling into Julian's attic bedroom. A high wind had blown up, as if from nowhere. It seemed ominous and I thanked God that Julian hadn't been there.

The next day Julian rang to tell me he had arrived safely and was in the Dakota apartment with Yoko, Sean and various members of staff. Hundreds of people were camped outside the building, but Sean didn't yet know of John's death so those inside were trying to keep up the pretense of normality until Yoko felt ready to tell him. Julian sounded tired, but he said that John's assistant, Fred Seaman, had met him at the airport and had been very kind to him. It was a relief to know that someone was looking out for my son.

In Wales, life had to go on. We couldn't afford to close the bistro and John and Angie couldn't manage in the busy season without me, so we opened for business. I cleaned, cooked, served customers and looked after my mother, all the while feeling numb and disconnected. While I got on with the business of life I had to contain my grief, but as headlines about John continued to dominate the news and his music soared up the charts, memories of him, our life together and all we had shared played constantly through my mind. The many hundreds of sympathy cards and messages I received from those who had known John, and those who had simply loved the man and his music, helped. But as I struggled through a disjointed, empty couple of weeks in the lead-up to Christmas, with my son away and my marriage on the rocks, I felt overwhelmed with sadness, frustration and loss. How could the man I had loved for so long and with such fierce, passionate intensity be gone? How could his vibrant life energy and his unique creativity have been snuffed out by a madman's bullet? And how could he have left his two sons without a father when they both needed him so much?

One early December afternoon in 1980 my friend Angie and I were in the little bistro we ran in north Wales, putting up the Christmas decorations. It was a cold, dark afternoon, but the atmosphere inside was bright and warm. We'd opened a bottle of wine and were hanging baubles on the tree and festive pictures on the walls. Laughing, we pulled a cracker and the toy inside fell onto the floor. I bent to pick it up and shivered when I saw it was a small plastic gun. It seemed horribly out of place among the tinsel and paper chains.

The next day I went to stay with my friend Mo Starkey in London. I couldn't really spare the time during the busy pre-Christmas season, but my lawyer had insisted I go to sign some legal papers, so I took the train, planning to return the following day. I left my husband and Angie to look after things in my absence. Angie was the ex-wife of Paul McCartney's brother, Mike, and after her marriage broke up she'd come to work for us, living in the small flat above the bistro.

It was always good to see Mo. We'd been friends since 1962, when I was John's girlfriend and she was the teenage fan who fell in love with Ringo at the Cavern. Ringo and Mo had married eighteen months after us, and in the days when the Beatles were traveling all over the world, she and I had spent a lot of time together. Her oldest son, Zak, was fifteen, a year and a half younger than my son Julian, and the boys had always been playmates.

When Mo and Ringo parted in 1974 she had been so heartbroken that she got on a motorbike and drove it straight into a brick wall, badly injuring herself. She had been in love with him since she was fifteen and his public appearances with his new girlfriend, American actress Nancy Andrews, had devastated her.

After the split Mo, still only twenty-seven, had moved into a house in the London neighborhood Maida Vale with her three children, Zak, eight, Jason, six, and Lee, three. Because of the injuries she'd received in the motorbike accident she had plastic surgery on her face and was delighted with the result, which she felt made her look better than she had before. Gradually she'd begun to get over Ringo, and she had a brief fling with George Harrison before she began to see Isaac Tigrett, millionaire owner of the Hard Rock Café chain.

The evening I arrived Mo had her usual houseful of people. Her mother, Flo, lived with her, as well as the children and their nanny. Mo always had an open house and that evening some old friends of ours, Jill and Dale Newton, had joined us for dinner. The nanny had cooked a huge meal, and later, Jill and Dale, Maureen and I sat over a couple of bottles of wine and talked about old times. After a while the conversation turned to the death of Mal Evans, the Beatles' former road manager. Mal had been a giant of a man, generous and soft-hearted. We'd known him since the early days when he'd worked for the post office and moonlighted as a bouncer at the Cavern Club. When the Beatles began to be successful they took him on to work for them.

Mal had been a faithful friend to the boys and was especially close to John: they got on incredibly well and, with the Beatles' other loyal roadie, Neil Aspinall, he had been on every tour, organizing, trouble-shooting, protecting and looking after them.

When the Beatles broke up Mal had been lost. He'd gone to live in Los Angeles where he began drinking and taking drugs. It was there, on January 4, 1976, that the police had been called by his girlfriend during a row. She claimed that Mal had pulled a gun on her, and when they burst into the apartment the officers found Mal holding a gun. Apparently he pointed it at them before they shot him. It was only after he died that they found the gun wasn't loaded. It was a tragic story, and we could only imagine that Mal had been under the influence of drugs. The Mal we knew could no more have shot someone than flown to the moon. Whatever the true story, his death had shocked us all and that night, our talk around Mo's fireplace was of what a good man he had been and how awful his premature death was. To us, the idea of being shot was almost unimaginable-how could it have happened to such a good friend?

After a while I went to bed. I knew the others would carry on talking and drinking until the early hours, but I wanted a good night's sleep as I had to get up early in the morning to catch the train home.

I was asleep in the spare room when screams woke me. It took me a few seconds to realize that they were Mo's. At that moment she burst into my room: "Cyn, John's been shot. Ringo's on the phone-he wants to talk to you."

I don't remember getting out of bed and going down the stairs to the phone. But Ringo's words, the sound of his tearful voice crackling over the transatlantic line, was crystal clear: "Cyn, I'm so sorry, John's dead."

The shock engulfed me like a wave. I heard a raw, tearing sob and, with that strange detachment that sudden shock can trigger, realized I was making the noise. Mo took the phone, said good-bye to Ringo, then put her arms around me. "I'm so sorry, Cyn," she sobbed.

In my stunned state I had only one clear thought. My son-our son-was at home in bed: I had to get back so that I could tell him about his father's death. He was seventeen and history was repeating itself in a hideous way: both John and I had lost a parent at that age.

I rang my husband and told him I was on the way and not to tell Julian what had happened. My marriage-the third-had been strained for some time and, in my heart of hearts, I knew it was going to end, but he was supportive. "Of course," he said. "I'll do my best to keep it from him." By the time I was dressed and had gathered my things, Mo had organized a car and a driver to take me to Wales. She insisted on coming too, with Zak. "I'll bring Julian back to stay with us if he needs to get away from the press," she promised.

John had been shot in New York at 10:50 p.m. on December 8. The time difference meant it was 3:50 a.m. on December 9 in Britain. Ringo had rung us barely two hours after it had happened, and we were on the road by seven. It was a four-hour drive to north Wales, and during the journey I stared out of the window in the gray dawn and thought of John.

In the jumble of thoughts whirring around my mind two kept recurring. The first was that nine had always been a significant number for John. He was born on October 9 and so was his second son, Sean. His mother had lived at number 9; when we met my house number had been 18 (the two digits of which add up to 9) and the hospital address Julian was born in was number 126 (again, each digit adds up to 9). Brian Epstein had first heard the Beatles play on the ninth of the month, they had got their first record contract on the ninth and John had met Yoko on the ninth. The number had cropped up in John's life in numerous other ways, so much so that he wrote three songs around it-"One After 909," "Revolution 9" and "#9 Dream." Now he had died on the ninth-an astonishing coincidence by any reckoning.

My second thought was that for the past fourteen years John had lived with the fear that he would be shot. In 1966 he'd received a letter from a psychic, warning that he would be shot while he was in the States. We were both upset by that: the Beatles were about to do their last tour of the States and, of course, we thought the warning referred to that trip. He had just made his infamous remark about the Beatles being more popular than Christ and the world was in an uproar about it-crank letters and warnings arrived by every post. But that one had stuck in his mind.

Afraid as he was, he went on the tour, and apologized reluctantly for the remark. When he got home in one piece we were both relieved. But the psychic's warning remained in his mind and from then on it seemed that he was looking over his shoulder, waiting for the gunman to appear. He often used to say, "I'll be shot one day." Now, unbelievably, tragically, he had been.

We reached Ruthin by mid-morning, and as we rounded the corner into what was normally a sleepy little town, my heart sank. There was no way that my husband could have kept the news from Julian: the town was packed with press. Dozens of photographers and reporters filled the square, the streets to our house and the bistro.

Amazingly we managed to park a few streets away and slip in through the back door, without being spotted by the crowd at the front. Inside my husband was pacing up and down restlessly. My mother, who lived above the bistro with Angie, was peering anxiously at the crowd from behind a drawn curtain. She was seventy-seven and suffering from the early stages of Alzheimer's. Confused by the crowds outside, she had no idea what was going on.

I looked at my husband, the question unspoken. Did Julian know? He nodded toward the stairs. A minute later Julian came running down. I held out my arms to him. He came over to me and his lanky teenage frame crumpled into my lap. He wrapped his arms around my neck and sobbed onto my shoulder. I hugged him and we cried together, both heartbroken at the awful, pointless waste that his father's death represented.

Mo had busied herself making tea, while Zak sat quietly nearby, not knowing what to say or do. While we drank the tea we talked about what to do. Maureen offered to take Julian back to London, but he said, "I want to go to New York, Mum. I want to be where Dad was." Although the idea alarmed me, I understood.

Maureen and Zak hugged us and left, then Julian and I went up to the bedroom to ring Yoko. We were put straight through to her, and she agreed that she would like Julian to join her. She said she would organize a flight for him that afternoon. I told her I was worried about the state he was in, but Yoko made it clear that I was not

welcome. "It's not as though you're an old schoolfriend of mine, Cynthia." It was blunt, but I accepted it: there is no place for an ex-wife in public grieving.

A couple of hours later my husband and I drove Julian to Manchester airport. The press spotted us as we left home, but when they saw our faces they drew back and let us pass. I was grateful. We sat through the two-hour drive in virtual silence. I was exhausted by the depth of my emotions and by the need to hold back my pain and attend to the necessary practicalities, for Julian's sake.

At the airport I watched him being led off by a flight attendant, his shoulders bowed, his face chalk white. I knew he would sit on the plane surrounded by people reading newspapers with headlines about his father's death splashed across their front pages and I longed to run after him. Before he disappeared through the gate he turned back and waved. He looked painfully young and I ached at having to let him go.

Back in Wales the press was still camped outside our door in huge numbers-there wasn't a spare room left in town. Years later, when she was hosting the British talk show This Morning, Judy Finnegan told me that she had been a young reporter among that throng. "I felt for you," she told me. "You looked absolutely shattered."

I was furious when my husband let one of the more persuasive journalists, a man who said he was writing a book about John, into our home. Later he claimed that I gave him a lengthy interview, but in fact I said just a few words, then asked him to leave. I was in no state and no mood to give an interview. I fell into bed and lay, numb and exhausted, too wrung out for any more tears, trying to take in the enormity of what had happened.

That night, after I drifted into a shallow sleep, there was a terrible crash. I leapt up, screaming-it was as though a bomb had gone off. I ran outside in my nightdress and saw that the chimney pot on our roof had crashed through the ceiling into Julian's attic bedroom. A high wind had blown up, as if from nowhere. It seemed ominous and I thanked God that Julian hadn't been there.

The next day Julian rang to tell me he had arrived safely and was in the Dakota apartment with Yoko, Sean and various members of staff. Hundreds of people were camped outside the building, but Sean didn't yet know of John's death so those inside were trying to keep up the pretense of normality until Yoko felt ready to tell him. Julian sounded tired, but he said that John's assistant, Fred Seaman, had met him at the airport and had been very kind to him. It was a relief to know that someone was looking out for my son.

In Wales, life had to go on. We couldn't afford to close the bistro and John and Angie couldn't manage in the busy season without me, so we opened for business. I cleaned, cooked, served customers and looked after my mother, all the while feeling numb and disconnected. While I got on with the business of life I had to contain my grief, but as headlines about John continued to dominate the news and his music soared up the charts, memories of him, our life together and all we had shared played constantly through my mind. The many hundreds of sympathy cards and messages I received from those who had known John, and those who had simply loved the man and his music, helped. But as I struggled through a disjointed, empty couple of weeks in the lead-up to Christmas, with my son away and my marriage on the rocks, I felt overwhelmed with sadness, frustration and loss. How could the man I had loved for so long and with such fierce, passionate intensity be gone? How could his vibrant life energy and his unique creativity have been snuffed out by a madman's bullet? And how could he have left his two sons without a father when they both needed him so much?

Recenzii

“Lennon’s eyewitness testimony vividly captures the time and place and the characters . . . her portrait of John is loving but candid.” —Washington Post

“A welcome window into a period that’s typically narrated at breakneck pace, [providing] a gentle reminder that John Lennon was a human being . . . before he was a piece of history.” —Detroit Free Press

“[Cynthia Lennon’s] portrait reveals an immensely talented and driven man who was capable of great passion, affection, and loyalty, but whose inability to handle confrontation and tendency toward flight from painful realities led him to abandon his family when the going got tough.” —Buffalo News

“A welcome window into a period that’s typically narrated at breakneck pace, [providing] a gentle reminder that John Lennon was a human being . . . before he was a piece of history.” —Detroit Free Press

“[Cynthia Lennon’s] portrait reveals an immensely talented and driven man who was capable of great passion, affection, and loyalty, but whose inability to handle confrontation and tendency toward flight from painful realities led him to abandon his family when the going got tough.” —Buffalo News

Descriere

The late John Lennon's first wife Cynthia recalls her romance and marriage and the rise of the Beatles with the loving honesty of an insider, offering new and fascinating insights.