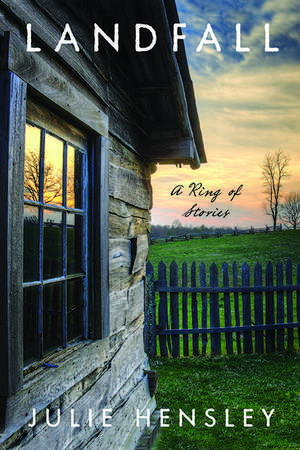

Landfall: A Ring of Stories: Non/Fiction Collection Prize

Autor Julie Hensleyen Limba Engleză Paperback – 14 apr 2016

In this ring of connected short stories, grounded in the fictional town of Conrad’s Fork, Kentucky, everyone is staging some sort of escape. A woman harboring the dark truth about her youngest daughter’s birth, a new teacher suddenly under suspicion after a student’s disappearance, a young girl witnessing her older sister’s sexual awakening: all the people in this Appalachian community suffer a paralyzed desire in response to the stagnancy and exposure they experience in their small town. Landfall: A Ring of Stories weaves together the voices of two generations of mountain families in which secrets are carefully guarded—even from closest kin. One by one, those who leave confront the pull of the land and the people they’ve left behind. Perhaps Conrad’s Fork will save them, or, perhaps, in the wake of urban encroachment and shifting family systems, they will save it.

Preț: 117.44 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 176

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.47€ • 23.55$ • 18.58£

22.47€ • 23.55$ • 18.58£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 21 martie-04 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780814252697

ISBN-10: 0814252699

Pagini: 232

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Ohio State University Press

Seria Non/Fiction Collection Prize

ISBN-10: 0814252699

Pagini: 232

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Ohio State University Press

Seria Non/Fiction Collection Prize

Recenzii

“In Landfall, Julie Hensley has created an Appalachian community populated with people I’ve come to know as neighbors, whose loves and losses feel like my own. It’s easy to forget that Conrad’s Fork is a fictional place and that, as vividly as their intertwined lives are rendered on the page, these are fictional characters. It’s hard to stop reading as Hensley unravels in masterful prose the ties that bind them to each other and home. Landfall is a beautiful book, and Julie Hensley is an immensely gifted writer to watch. —Amy Greene

“Landfall signals the emergence of a masterful new writer. Each sentence is a gem, polished up so that each paragraph, each page, and each story shines, resulting in a book that is so lovely and lyrical that readers will feel as if they are luxuriating in a sea of words. Hensley’s wonderful fiction has been showing up in some of the best literary journals for years now, and I’m so glad that we finally have a book to savor—and to share with others. Landfall is a wonder. So is Julie Hensley. —Silas House, author of Clay’s Quilt and Same Sun Here

Notă biografică

Julie Hensley is Associate Professor of Creative Writing at Bluegrass Writers Studio at Eastern Kentucky University and the author of The Language of Horses, a poetry chapbook.

Extras

Bread Pudding

Helen 1965

This is not the story of my lover. And neither is it the story of my girls, although both their beginnings are gnarled somewhere in the thick of what I’m going to tell you. This is my husband’s story because I label it so. I have never told my daughters, but I suspect if I could tell it to them—tell it the way it happened and the way it plays out in my mind—they would say it is first my story.

More than once my girls and I have packed a lunch and driven into the hollow, have climbed the washed-out logging trail that twists up to Cedar Creek Falls, and have had a picnic there amidst the ruins of an old farmstead. You can see, if you know where to look, the foundation of a cabin and the ruins of a family cemetery, limestone grave markers covered in nettle and moss. We’ve found tangled pumpkin vines, the remnants of an abandoned garden, flowering yellow in early summer. The plants continue to grow without reseeding or direct sunlight, even after a hundred years have passed. That is the way it is with this story.

I am allowed my secret. We all move around it carefully, knowingly. It grows larger and greener like the grass the cows leave untouched around last year’s manure. The people I love radiate out from a season of loss.

The summer of my fifth wedding anniversary was the driest in forty years. By July, the corn still hadn’t risen past the fence posts. The leaves pulled away from the stalks, shriveled, and curled toward the ground. My husband, Neil, who planted only about 20 acres of corn, grew it mostly for silage. But each week I would fill the back of the International with the best ears. This was in the time before the trees bore fruit, when my mother and I ran a roadside vegetable stand on summer weekends. I was strong then, and I would move down the rows with ease, cradling the crates of corn against my hip, sending the contents rumbling into the truck bed when I reached the end of a row. Cora, from the time she could walk, would sit in the shade of the tailgate sifting dirt through her fingers and sorting the pebbles into meaningful piles.

That year, instead of the quiet sigh of summer, the field was a hollow rattle around me. Forest fires were burning on the backside of Old Nag Mountain, and although the sky thickened gray in the afternoon, it was only ash hanging in the air. Neil worried for the fruit trees. The young orchard, which in ten years was to be our primary income, might not recover. Twice he filled five gallon buckets from the pump by the barn and drove—with water sloshing over the sides of the truck—through the lines of new trees, pouring carefully around the base of each one.

Neil brought home the fire truck and the man the same morning in July. The truck was already an antique, a 1934 American La Franc. Its red paint had faded to orange, and the words Big Stone Gap Hose Company stretched in a faded arc along each door. The cab was an open cockpit. Coiled in back were flat, gray loops of hose.

Rosario, who was short and thick, and all hands and shoulders, was to be the night irrigator. His hair was slicked back with water. It looked dark and clean in a way that reminded me of the old-fashioned men of my girlhood, my father and his friends milling around outside church. His skin was brown and mottled like pecan shells.

Rosario refused dinner, so when the rest of us gathered beneath the grape arbor, lawn chairs pulled up to the oak slab table, Neil told the man’s story for him. Bees murmured overhead even though the grapes were small and hard from the lack of rain.

“He’s originally from Chiapas,” said Neil as he took the plate of cold chicken from my mother, “but he’s lived in the states since he was nine. He says his family just kept working and moving. Always on other people’s land. Christ, it makes you realize how easy you got it, don’t it?” Cora was seated in his lap, and he had to pull her hands away from his tea. He gave her the cup with her milk, the one with dancing rabbits.

“Does he even speak English?” Dad wanted to know.

“Sure,” said Neil. “And he really knows irrigation work. Been doing it the last few years out in California and Arizona.”

“There’s a good many of our boys looking for work right here.”

Dad was right. Young vets, only recently returned, hung around on the sidewalk in front of High’s Dairy Mart. Sometimes they waited with backpacks and cardboard signs along Route 38, thumbs extended in the wake of wind and horns from the rattling poultry trucks.

“Well, this one made himself known to me.” My husband tore pieces of chicken from the bone and handed them to Cora, waving the flies away from their plate. He no longer worried about pleasing my father. “He saw me looking over the hoses, and he told me that he could rig up a pump and have the whole works going in two days.”

“Where are we going to put him,” asked my mother. The farmhouse already felt crowded. The only bedroom not in use was cluttered with boxes of seasonal clothes and holiday decorations. Her sewing machine was arranged there on a folding card table. In the end, Neil cleared out the tack room, and Rosario settled in the barn.

Helen 1965

This is not the story of my lover. And neither is it the story of my girls, although both their beginnings are gnarled somewhere in the thick of what I’m going to tell you. This is my husband’s story because I label it so. I have never told my daughters, but I suspect if I could tell it to them—tell it the way it happened and the way it plays out in my mind—they would say it is first my story.

More than once my girls and I have packed a lunch and driven into the hollow, have climbed the washed-out logging trail that twists up to Cedar Creek Falls, and have had a picnic there amidst the ruins of an old farmstead. You can see, if you know where to look, the foundation of a cabin and the ruins of a family cemetery, limestone grave markers covered in nettle and moss. We’ve found tangled pumpkin vines, the remnants of an abandoned garden, flowering yellow in early summer. The plants continue to grow without reseeding or direct sunlight, even after a hundred years have passed. That is the way it is with this story.

I am allowed my secret. We all move around it carefully, knowingly. It grows larger and greener like the grass the cows leave untouched around last year’s manure. The people I love radiate out from a season of loss.

The summer of my fifth wedding anniversary was the driest in forty years. By July, the corn still hadn’t risen past the fence posts. The leaves pulled away from the stalks, shriveled, and curled toward the ground. My husband, Neil, who planted only about 20 acres of corn, grew it mostly for silage. But each week I would fill the back of the International with the best ears. This was in the time before the trees bore fruit, when my mother and I ran a roadside vegetable stand on summer weekends. I was strong then, and I would move down the rows with ease, cradling the crates of corn against my hip, sending the contents rumbling into the truck bed when I reached the end of a row. Cora, from the time she could walk, would sit in the shade of the tailgate sifting dirt through her fingers and sorting the pebbles into meaningful piles.

That year, instead of the quiet sigh of summer, the field was a hollow rattle around me. Forest fires were burning on the backside of Old Nag Mountain, and although the sky thickened gray in the afternoon, it was only ash hanging in the air. Neil worried for the fruit trees. The young orchard, which in ten years was to be our primary income, might not recover. Twice he filled five gallon buckets from the pump by the barn and drove—with water sloshing over the sides of the truck—through the lines of new trees, pouring carefully around the base of each one.

Neil brought home the fire truck and the man the same morning in July. The truck was already an antique, a 1934 American La Franc. Its red paint had faded to orange, and the words Big Stone Gap Hose Company stretched in a faded arc along each door. The cab was an open cockpit. Coiled in back were flat, gray loops of hose.

Rosario, who was short and thick, and all hands and shoulders, was to be the night irrigator. His hair was slicked back with water. It looked dark and clean in a way that reminded me of the old-fashioned men of my girlhood, my father and his friends milling around outside church. His skin was brown and mottled like pecan shells.

Rosario refused dinner, so when the rest of us gathered beneath the grape arbor, lawn chairs pulled up to the oak slab table, Neil told the man’s story for him. Bees murmured overhead even though the grapes were small and hard from the lack of rain.

“He’s originally from Chiapas,” said Neil as he took the plate of cold chicken from my mother, “but he’s lived in the states since he was nine. He says his family just kept working and moving. Always on other people’s land. Christ, it makes you realize how easy you got it, don’t it?” Cora was seated in his lap, and he had to pull her hands away from his tea. He gave her the cup with her milk, the one with dancing rabbits.

“Does he even speak English?” Dad wanted to know.

“Sure,” said Neil. “And he really knows irrigation work. Been doing it the last few years out in California and Arizona.”

“There’s a good many of our boys looking for work right here.”

Dad was right. Young vets, only recently returned, hung around on the sidewalk in front of High’s Dairy Mart. Sometimes they waited with backpacks and cardboard signs along Route 38, thumbs extended in the wake of wind and horns from the rattling poultry trucks.

“Well, this one made himself known to me.” My husband tore pieces of chicken from the bone and handed them to Cora, waving the flies away from their plate. He no longer worried about pleasing my father. “He saw me looking over the hoses, and he told me that he could rig up a pump and have the whole works going in two days.”

“Where are we going to put him,” asked my mother. The farmhouse already felt crowded. The only bedroom not in use was cluttered with boxes of seasonal clothes and holiday decorations. Her sewing machine was arranged there on a folding card table. In the end, Neil cleared out the tack room, and Rosario settled in the barn.

Descriere

In this ring of connected short stories, grounded in the fictional town of Conrad’s Fork, Kentucky, everyone is staging some sort of escape.