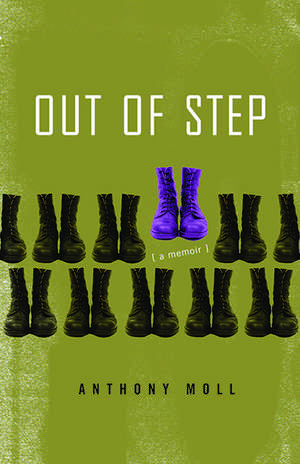

Out of Step: A Memoir: Non/Fiction Collection Prize

Autor Anthony Mollen Limba Engleză Paperback – 18 iul 2018 – vârsta ani

Winner of 2018 Lambda Book Award (Bisexual Nonfiction)

What makes a pink-haired queer raise his hand to enlist in the military just as the nation is charging into war? In his memoir, Out of Step, Anthony Moll tells the story of a working-class bisexual boy running off to join the army in the midst of two wars and the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” era. Set against the backdrop of hypermasculinity and sexual secrecy, Moll weaves a queer coming-of-age story.

Out of Step traces Moll’s development through his military service, recounting how the army both breaks and builds relationships, and what it was like to explore his queer identity while also coming to terms with his role in the nation’s ugly foreign policy. From a punk, nerdy, left-leaning, poor boy in Nevada leaving home for the first time to an adult returning to civilian life and forced to address a world more complicated than he was raised to believe, Moll’s journey isn’t a classic flag-waving memoir or war story—it’s a tale of finding one’s identity in the face of war and changing ideals.

What makes a pink-haired queer raise his hand to enlist in the military just as the nation is charging into war? In his memoir, Out of Step, Anthony Moll tells the story of a working-class bisexual boy running off to join the army in the midst of two wars and the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” era. Set against the backdrop of hypermasculinity and sexual secrecy, Moll weaves a queer coming-of-age story.

Out of Step traces Moll’s development through his military service, recounting how the army both breaks and builds relationships, and what it was like to explore his queer identity while also coming to terms with his role in the nation’s ugly foreign policy. From a punk, nerdy, left-leaning, poor boy in Nevada leaving home for the first time to an adult returning to civilian life and forced to address a world more complicated than he was raised to believe, Moll’s journey isn’t a classic flag-waving memoir or war story—it’s a tale of finding one’s identity in the face of war and changing ideals.

Preț: 140.26 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 210

Preț estimativ în valută:

26.84€ • 28.12$ • 22.19£

26.84€ • 28.12$ • 22.19£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 07-14 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780814254820

ISBN-10: 0814254829

Pagini: 116

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Mad Creek Books

Seria Non/Fiction Collection Prize

ISBN-10: 0814254829

Pagini: 116

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Mad Creek Books

Seria Non/Fiction Collection Prize

Recenzii

“Out of Step is not just Moll’s memoir; it is a loving and empathetic portrayal of those around him, paying explicit attention to the vulnerable, the outcast and the misunderstood.” —Times Literary Supplement

“Filled with raw emotion, wry humor, and unselfconscious reflection, [Out of Step] conveys Moll’s unwavering sense of self in a refreshing, inspiring way.” —Foreword Reviews

“Moll’s evocation of his army life is deadly serious yet always insightful as he questions himself and, finally, tells the truth he discovers.” —Booklist

“Out of Step is the story of a young man trying to find his place in the disparate worlds of American military and civilian life. . . . Moll’s take is thoughtful and fair, both critical of the military while recognizing how it built him.” —Shelf Awareness

“Out of Step is a memoir-in-essays of place and poverty and sexuality and the search for self against the backdrop of military life during the final years of 'Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.' Moll’s searing clarity, ear for language, and extraordinary range of storytelling methods imbue this essay collection with the musicality of a symphony and the intimacy of a treasured mix-tape. This is a stunning and important book.” —Michael Kardos

“Out of Step is a page turner—a roller coaster that readers will never forget. Moll has a gift for crafting brilliant sentences and has created the type of contemporary memoir that reminds me of why I can’t live without writing. I highly recommend.” — D. Watkins, New York Times best-selling author of The Beast Side and The Cook Up

Notă biografică

Anthony Moll is a Baltimore-based writer and educator. His creative work has appeared in Gertrude Journal, Assaracus, jubilat, and more. Anthony holds an MFA in Creative Writing and Publishing Arts and has taught writing at both public and private universities.

Extras

I’d like to say I joined the military unmarked, that I arrived at the Military Entrance Processing Station, a multipurpose facility that acts as everything from a clinic for physical exams to an administrative office for processing those entering the military, as young and pure as a Renaissance bronze. Yet the truth of my enlistment is that the physician inspecting my young body with latex gloves missed neither the tiny scar on my forehead where I had fallen from top bunk onto a Tonka truck as a child, nor the dime-sized Mongolian Blue Spot decorating my backside. Still, aside from these minor blemishes, my young, soft body raised a hand and swore the oath of enlistment without any real damage at eighteen years.Teeth

The first mark came early. As my platoon huddled together, celebrating a well-run obstacle course in the middle of our basic-training experience, a helmet-clad head jerked back toward my face, sending a good portion of my front teeth to the back of my throat.

Basic training being the frenzied experience that it is, the emergency dentist at the clinic asked if I was experiencing any sensitivity in the injured teeth. Me being in no pain and terrified of the backlash of my drill sergeants should I miss training, I insisted I felt fine, and walked around for the remainder of basic training, and several weeks that followed, looking like Lloyd Christmas.

...

Hands

I don’t belong here. The Baltimore Veterans Affairs Hospital is for old men. Veterans with mesh caps with Korea or Vietnam emblazoned across them. Broken men. Worn bodies. A thin man in camouflage pants wheels an oxygen tank behind him. A thick man showing off his tattooed arms coughs a wet cough into a towel.

I wish I could say that I shattered both of my hands doing something heroic. How might a warrior injure himself? Charging a hill? Shrapnel? Gulf War Syndrome maybe, tiny desert sands stirred with weaponized chemicals. Damp jungle air mixed with defoliating herbicides.

In my early twenties, I broke my hands skateboarding down a hill. I raced down the hill, without any protective gear, as quickly as I could, allowing the hot desert air to slap at my face. When I lost control, I tried to bail, tried to feign running through the air fast enough to hit the ground and keep moving. When I came down, I didn’t stand a chance. My hands hit first, and gravity scraped me along the asphalt for several feet before leaving me to rest. My army buddies told me earlier that day it was a dangerous hill to speed down, and I was stupid for trying. Later that week, my boss threatened to charge me with dereliction of duty for skateboarding when I was on-call. (Soldiers have this myth, and I never knew whether or not it was true, that troops engaging in self-destructive behaviors can be charged with damaging government property—themselves.) The doctor cut open both of my hands and tried to bolt the bones back together. When he opened up the left hand, the bone was worse off than he thought, so he slipped in a cadaver donor’s scaphoid while I was under for surgery. He told me just as casual as that, the day after, in a recovery bed.

Army doctors get away with a lot.

In a cubicle where I wait for the benefits administrator to come talk to me, there is a pamphlet for Atomic Veterans. That’s what Veterans Affairs calls vets exposed to ionizing radiation during America’s atomic era. It’s common enough that they have a name for it. Vets stationed outside of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but also veterans near testing ranges in the U.S., and vets who were intentionally exposed to radiation for the sake of testing its impact on the human body.

Many vets in these latter categories were sworn to silence, and for decades they couldn’t legally discuss their exposure to anyone, including medical professionals. By the time a law came along to allow them to seek the treatment that many of them need, many were already dead. Those still living had been carrying the secret for so long that they still didn’t come forward. The pamphlet in front of me is an effort to reach out to those atomic veterans, to let them know that they are legally able to speak up, and to seek treatment for their wounds.

I’m here because I need medical insurance, and because I need to document skateboarding injuries that Veterans Affairs considers “service-related” because I was in the army when they happened.

I don’t belong here.

The first mark came early. As my platoon huddled together, celebrating a well-run obstacle course in the middle of our basic-training experience, a helmet-clad head jerked back toward my face, sending a good portion of my front teeth to the back of my throat.

Basic training being the frenzied experience that it is, the emergency dentist at the clinic asked if I was experiencing any sensitivity in the injured teeth. Me being in no pain and terrified of the backlash of my drill sergeants should I miss training, I insisted I felt fine, and walked around for the remainder of basic training, and several weeks that followed, looking like Lloyd Christmas.

...

Hands

I don’t belong here. The Baltimore Veterans Affairs Hospital is for old men. Veterans with mesh caps with Korea or Vietnam emblazoned across them. Broken men. Worn bodies. A thin man in camouflage pants wheels an oxygen tank behind him. A thick man showing off his tattooed arms coughs a wet cough into a towel.

I wish I could say that I shattered both of my hands doing something heroic. How might a warrior injure himself? Charging a hill? Shrapnel? Gulf War Syndrome maybe, tiny desert sands stirred with weaponized chemicals. Damp jungle air mixed with defoliating herbicides.

In my early twenties, I broke my hands skateboarding down a hill. I raced down the hill, without any protective gear, as quickly as I could, allowing the hot desert air to slap at my face. When I lost control, I tried to bail, tried to feign running through the air fast enough to hit the ground and keep moving. When I came down, I didn’t stand a chance. My hands hit first, and gravity scraped me along the asphalt for several feet before leaving me to rest. My army buddies told me earlier that day it was a dangerous hill to speed down, and I was stupid for trying. Later that week, my boss threatened to charge me with dereliction of duty for skateboarding when I was on-call. (Soldiers have this myth, and I never knew whether or not it was true, that troops engaging in self-destructive behaviors can be charged with damaging government property—themselves.) The doctor cut open both of my hands and tried to bolt the bones back together. When he opened up the left hand, the bone was worse off than he thought, so he slipped in a cadaver donor’s scaphoid while I was under for surgery. He told me just as casual as that, the day after, in a recovery bed.

Army doctors get away with a lot.

In a cubicle where I wait for the benefits administrator to come talk to me, there is a pamphlet for Atomic Veterans. That’s what Veterans Affairs calls vets exposed to ionizing radiation during America’s atomic era. It’s common enough that they have a name for it. Vets stationed outside of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but also veterans near testing ranges in the U.S., and vets who were intentionally exposed to radiation for the sake of testing its impact on the human body.

Many vets in these latter categories were sworn to silence, and for decades they couldn’t legally discuss their exposure to anyone, including medical professionals. By the time a law came along to allow them to seek the treatment that many of them need, many were already dead. Those still living had been carrying the secret for so long that they still didn’t come forward. The pamphlet in front of me is an effort to reach out to those atomic veterans, to let them know that they are legally able to speak up, and to seek treatment for their wounds.

I’m here because I need medical insurance, and because I need to document skateboarding injuries that Veterans Affairs considers “service-related” because I was in the army when they happened.

I don’t belong here.

Descriere

A queer coming-of-age-story set against the backdrop of the U.S. military during the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” era.