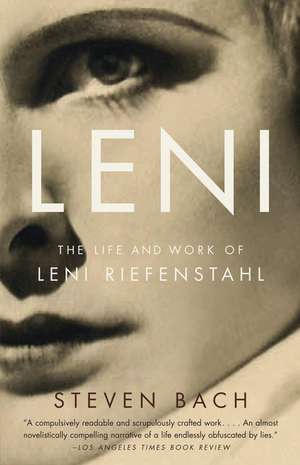

Leni: The Life and Work of Leni Riefenstahl

Autor Steven Bachen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 ian 2008

A riveting and illuminating biography of one of the most fascinating and controversial personalities of the twentieth century.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 69.98 lei 43-57 zile | |

| Vintage Books USA – 31 ian 2008 | 119.96 lei 22-36 zile | |

| Little, Brown Book Group – 31 mai 2008 | 69.98 lei 43-57 zile |

Preț: 119.96 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 180

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.95€ • 24.03$ • 19.11£

22.95€ • 24.03$ • 19.11£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 10-24 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307387752

ISBN-10: 0307387755

Pagini: 386

Ilustrații: 32 PP B&W

Dimensiuni: 133 x 202 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.41 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 0307387755

Pagini: 386

Ilustrații: 32 PP B&W

Dimensiuni: 133 x 202 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.41 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

Steven Bach is the author of two previous biographies, Marlene Dietrich: Life and Legend and Dazzler: The Life and Times of Moss Hart. He was in charge of worldwide production for United Artists, where he was involved in such films as Raging Bull, Manhattan, The French Lieutenant's Woman, and Heaven's Gate, about which he wrote the bestseller Final Cut. He teaches at Bennington College and Columbia University and divides his time between New England and Europe.

Extras

CHAPTER ONE: METROPOLIS

I want to become something quite great.

—Leni Riefenstahl

Leni Riefenstahl created images from light and shadow, from movement, rhythm, passion, prodigious energy, physical courage, and driving, epic ambition. She had, she said, one subject—beauty—and searched for it in the natural world, mountain high and underwater deep; in the flags and torches of massed multitudes; in the struggle and transcendence of athletic competition; in the physical and erotic perfection of primitive warriors; and—from the beginning—in herself.

She was born Helene Amalia Bertha Riefenstahl on August 22, 1902, in Wedding, a sooty workers’ district on the industrial edges of Berlin. The population of the city was then two million going on four, with growth so rapid that street maps were obsolete before printers could produce them. Disgruntled civic planners disparaged Berlin as a “nowhere city,” a city “always becoming” that “never is,” but advocates of change hailed “progress” and thrilled to restless urban rhythms as full of expectancy as its air—the fabled Berliner Luft—and just as vital and intoxicating.

The onetime river trading post and its mushrooming suburbs would incorporate as Greater Berlin in 1920, by which time the boundaries of “Athens on the Spree” were vast enough to embrace Frankfurt, Stuttgart, and Munich put together. It was a parvenu metropolis compared to Paris, London, or Vienna with their Roman roots and ruins, but it was also—quite suddenly—the third largest metropolitan area in the world: loud, aggressive, and going places.

“The fastest city in the world!” they called Berlin when Leni was born there. It had been the capital of Germany, of what was grandly styled the Second Reich, for only thirty years, but empire builders in a hurry boasted of its modernity, unperturbed that horses still pulled trolleys through gaslit streets, that running water (hot or cold) was seldom encountered above the ground floor, and that the Berlin telephone directory was a twenty-six-page pamphlet. Crime and vice were no more rampant and no less colorful than in London, Paris, Buenos Aires, or New York. News of the day—or the minute—rolled off the presses in every political persuasion from the hundred dailies and weeklies that were published there in a babel of languages, making Berlin the liveliest, most densely concentrated center of journalism in all Europe.

Berlin’s boosters were too focused on the future to give more than a backward glance to such slums and laborers’ districts as Wedding or to the workers’ children, like Leni, growing up in them. Civic do-gooders nodded dutifully as Kaiser Wilhelm II reminded them of “the duty to offer to the toiling classes the possibility of elevating themselves to the beautiful.” One had only to point inferiors in the direction of the Hohenzollern Palace, the Tiergarten, the Victory Column, the broad canals and their 957 bridges (more than in Venice), the Pergamon Museum with its antiquities, the Reichstag with its “To the German People” promise carved in stone beneath its sheltering dome of steel and glass; or to the glittering theaters, operas, and hotels, the promenade streets such as tree-canopied Unter den Linden or the racier Kurfürstendamm (Bismarck’s answer to the Champs-Élysées) lined with shops and sidewalk cafés. If the toiling class infrequently abandoned the factory floors for tours of the more elegant venues of imperial Berlin, the kaiser graciously imparted his notions of art and the beautiful to them. “An art which transgresses the laws and barriers outlined by Me,” he explained, “ceases to be an art.” This rang with reassuring certainty to the aesthetically insecure and was a viewpoint that a later leader—a onetime painter of picture postcards and aspiring architect—would echo and that millions would accept with awed docility.

No city in Europe made such a cult of modernity. Berlin was rushing at the turn of the century to make up in future what it lacked in past, while custodians of nostalgia mourned “a vanished Arcadia” that had never truly been. Velocity, anonymity, and the cheek-by-jowl juxtaposition of promise and peril inspired songs, paintings, novels, plays, and—already flickering silently when Leni was born—films. Most of these works inspired awe and alienation, too, as ordinary Berliners wondered uneasily where all this urban energy would lead. Ambivalence would find disturbing graphic expression in the 1920s, but prophetic, ominous visions of city life that were dubbed “degenerate” from the start began appearing in the teens from such painters as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Emil Nolde, and Ludwig Meidner, who labeled his urban paintings “apocalyptic landscapes.”

Berlin-Wedding had scant time for art or musings on modernity. It was a dense warren of factories, foundries, and labor. It was blocks of tenements—called Mietskaserne, rent barracks—crowding blue-collar families into one- or two-room flats stacked five or six stories high around sunless courtyards where life was harsh and suicide a daily occurrence. “Tenement sickness” was shorthand for tuberculosis and rickets in Berlin, where the infant mortality rate was almost 20 percent when the nineteenth century ended and more than double that in Wedding, where it reached a high of 42 percent just after Leni was delivered there.

Wedding was poor but not without altruism and aspiration. Its mean streets offered shelter to the homeless in a spartan doss-house, and there was a small pond for ice-skating. Someone in 1905 rented out part of a courtyard shed as a photographer’s studio, and it wasn’t long before one-reel movies were being shot there. In 1912, Wedding established Berlin’s first crematorium to compensate for the scarcity and cost of open burial ground. Children played in courtyards; geraniums grew on windowsills; music and love got made; and by 1918, nearly 40 percent of all Berliners lived in tenement districts like it. We see their faces in the etchings and prints of Käthe Kollwitz; their bawdy, earthy pleasures titillate still in the sketches of Heinrich Zille, the poetic folk satirist and painter who knew them best and once observed that you can kill a man with his lodgings as well as you can with an ax.

“I hated the class system,” Leni Riefenstahl confided to a friend. She was turning ninety then, living in a sheltered lakeside villa in Bavaria, distant enough in every way from Wedding to give perspective on her birthplace, a basic tenement flat in the two-block-long Prinz-Eugen-Strasse. The rooms were first lodgings for first-time parents who were almost newlyweds, married in a civil ceremony on April 5, 1902, nearly five months before their daughter saw first light in August.

Leni’s father, Alfred Theodor Paul Riefenstahl, was not yet twenty-four when she was born. He was one of three boys and a girl born to Gustav and Amalie (née Lehmann) Riefenstahl in 1878 in the rural Brandenburg district surrounding Berlin. His father had been a blacksmith like his father before him, but Alfred—blond and burly and wearing an upturned Kaiser Wilhelm mustache—had been drawn to Berlin by economic opportunity. He styled himself “salesman” on documents, but in fact he was a plumber. He would in time build his own sanitation and ventilation business as domestic plumbing became standard: niceties turned into necessities, and a plumber into an entrepreneur.

Leni’s mother, Bertha Ida Scherlach Riefenstahl, was almost twenty-two when her daughter was born. Bertha was a willowy beauty with dark eyes, curly dark hair, and a determined jawline, all of which she passed on to her only daughter, who was born cross-eyed. Bertha herself was the eighteenth child of a mother who died giving birth to her in Wloclawek (now in Poland) on October 9, 1880. Shortly after Bertha’s mother died, her father—Leni’s carpenter grandfather—married his children’s nanny and fathered three more children, for a total of twenty-one.

There is a mystery here, one that might amount only to a niggling biographical puzzle were it not a hint of the shifting images of the past that Leni would manipulate as times changed and perspectives with them. Her background unavoidably aroused curiosity in the 1930s among powerful figures of the Third Reich as she rose to prominence among them. Rumors that she was Jewish—or partly so—gained currency in this period and traced an alleged line of Jewish descent through Bertha. Once aired, the rumors gained wide circulation in the European and American press during the early years of the Third Reich, though the allegations were never proved and were officially repudiated by the ultimate Third Reich authority, the Führer himself. Leni brushed the subject aside then and later as the poisoned residue of a malicious campaign orchestrated against her by Nazi propaganda minister Dr. Joseph Goebbels.

While some of the rumors were almost certainly inspired by Goebbels or others jealous of her position and privileges in the 1930s, not all of them were. Some of Leni’s closest friends and colleagues, including Dr. Arnold Fanck, the film director credited with Leni’s discovery, believed that Bertha was Jewish. As Leni’s onetime mentor and lover—and later a Nazi Party member—Fanck’s objectivity and veracity are not beyond challenge. Less equivocal is the testimony of art director Isabella Ploberger, who worked and lived with Leni and Bertha during World War II and took for granted that Bertha—“a lovely person, a fine person”—was Jewish. Ploberger believed that Goebbels knew, which accounted for his animosity.

There are documents, to be sure. Chief among them is Leni’s “Proof of Descent” (“Abstammungs-Nachweis”), the genealogical record of ancestry she prepared and submitted to the Reich’s film office in 1933 to validate Aryan descent, necessary to work in the German film industry. This document has long been available but never fully scrutinized, not even by the Nazis for whom it was prepared. Bertha is inscribed there as the child of the carpenter Karl Ludwig Friedrich Scherlach (born 1842) and Ottilie Auguste Scherlach (née Boia), born out of wedlock on January 24, 1863, to Friederika Boia and an unknown father. Though Ottilie Boia and Karl Scherlach are said to have married in the Silesian town of Woldenburg (Dobiegniew in modern Poland), no record of the marriage is known to exist, and their union may have been by common law. But what has gone unnoticed and unremarked is that Ottilie Boia could not possibly have been Bertha’s mother. Born in 1863, she could not have given birth to seventeen children before delivering Bertha in 1880. Ottilie was almost certainly the nanny that Leni’s carpenter grandfather married after his first wife died in delivering Bertha, the birth mother who became a nonperson in the genealogy Leni tendered to the Third Reich. As for Ottilie, she lived out her days as Bertha’s stepmother and Leni’s stepgrandmother in a modest flat in Charlottenburg, the comfortable Berlin suburb where the adolescent Leni ran to her for strudel and sympathy when Alfred Riefenstahl’s strict discipline became intolerable.

Third Reich genealogies required declaration of religion as well as race, and Leni’s states that her forebears were Protestant. They appear not to have been devout. Since 1850, every birth, including Leni’s, was recorded at a registry office rather than at a church after a christening (though Leni was confirmed as Protestant in a Berlin church at fifteen).

The city and culture in which Leni grew up were famously cosmopolitan; Jewish conversion to Christianity and cultural assimilation were commonplace, though racial identity, rather than religious, would be the Nazis’ standard when theirs became the only one that mattered. No known documents fill the gap in Leni’s ancestry, but the substitution of Bertha’s stepmother for her birth mother on a Third Reich genealogical document is hard to fathom without considering a motive touching on race, since defining race was the point of the exercise. What is not speculative is Leni’s ability to define and redefine her past as circumstance or occasion required. As for Bertha, Leni “loved her to distraction” until she died in 1965 at the age of eighty-four.

Alfred Riefenstahl inspired different emotions. He was a striver: rigid, efficient, conservative, and Leni’s rival for Bertha's attention. His business depended on Berlin, though he felt ill at ease there with his provincial background and views of family life, especially after Leni’s only sibling, a brother named Heinz, was born on March 5, 1906. Alfred’s burgeoning business allowed him to move the family to a larger flat in Berlin-Neukölln just before Heinz was born and Leni began school. The old neighborhood and the new were similar (both would be centers of Communist agitation after 1918), so it came as a relief when the family could afford weekend excursions to a lakeside village about an hour southwest of Berlin by suburban rail.

Zeuthen was idyllic, green, and distanced Leni and little Heinz from the city’s dangers. It was tranquil enough for hiking, swimming, and languidly watching clouds roll by. The cottage the family rented—and would eventually acquire—was a short walk through the woods to the railway line to Berlin and just across the lake from the Gasthaus run by Bertha’s older sister Olga, who had alerted them to the area in the first place.

As a child, Leni was contentedly solitary except for her brother, perhaps a trait acquired because the family moved so often. After the apartments in Wedding and Neukölln and the weekend cottage at Zeuthen, there would be other flats in Berlin in the Goltzstrasse and in the Yorckstrasse, nearer the center of the city and her father’s business. But she may have been solitary by choice because she saw herself as special and precocious and needed no supporting cast but Heinz and no audience but the indulgent Bertha, “always my best friend.”

She began reading at an early age, she tells us, and started writing poetry and plays at the age of five after an excursion to the theater to see a performance of Snow White. Though Alfred preferred bowling or hunting with friends, he now and then treated his family to a show, stoutly impervious to the stage magic that would become a “driving force” for his impressionable daughter and remained one for his wife.

Bertha had dreamed as a girl of going on the stage and may actually have done so. A photograph taken before her marriage shows her dressed in the kind of dashing finery a Floradora girl might have worn: a short-sleeved, knee-length dress trimmed in garlands of flowers repeated in her hat and on the open fan in her right hand, cocked saucily on her hip. She told Leni that she had prayed while carrying her, “Dear God, give me a beautiful daughter who will become a famous actress.” The seed planted, grew. What young girl could resist thinking herself the answer to a prayer?

“I dreamed my dreams,” Leni said, creating meadowland theatrics in which she played the leading role and the obliging Heinz became her willing prop. Like her poems and daily life, her plays excluded companionship and outsiders. “I allowed no people into my verses, only trees, birds and even insects.”

As she entered adolescence, she fantasized becoming a nun, but the cloister sounded confining and self-denial dreary. News reports of aviation exploits during the Great War excited images of adventure and daring. They also inspired her to imagine an entire airline industry on paper, scheduling flights between European cities and even calculating the price of tickets, as if emulating Alfred’s administration of his plumbing business. “There was in me some organizational talent struggling to emerge,” she remembered later, an aptitude that would prove indispensable when competing in the real world as a woman in a man’s universe.

From the Hardcover edition.

I want to become something quite great.

—Leni Riefenstahl

Leni Riefenstahl created images from light and shadow, from movement, rhythm, passion, prodigious energy, physical courage, and driving, epic ambition. She had, she said, one subject—beauty—and searched for it in the natural world, mountain high and underwater deep; in the flags and torches of massed multitudes; in the struggle and transcendence of athletic competition; in the physical and erotic perfection of primitive warriors; and—from the beginning—in herself.

She was born Helene Amalia Bertha Riefenstahl on August 22, 1902, in Wedding, a sooty workers’ district on the industrial edges of Berlin. The population of the city was then two million going on four, with growth so rapid that street maps were obsolete before printers could produce them. Disgruntled civic planners disparaged Berlin as a “nowhere city,” a city “always becoming” that “never is,” but advocates of change hailed “progress” and thrilled to restless urban rhythms as full of expectancy as its air—the fabled Berliner Luft—and just as vital and intoxicating.

The onetime river trading post and its mushrooming suburbs would incorporate as Greater Berlin in 1920, by which time the boundaries of “Athens on the Spree” were vast enough to embrace Frankfurt, Stuttgart, and Munich put together. It was a parvenu metropolis compared to Paris, London, or Vienna with their Roman roots and ruins, but it was also—quite suddenly—the third largest metropolitan area in the world: loud, aggressive, and going places.

“The fastest city in the world!” they called Berlin when Leni was born there. It had been the capital of Germany, of what was grandly styled the Second Reich, for only thirty years, but empire builders in a hurry boasted of its modernity, unperturbed that horses still pulled trolleys through gaslit streets, that running water (hot or cold) was seldom encountered above the ground floor, and that the Berlin telephone directory was a twenty-six-page pamphlet. Crime and vice were no more rampant and no less colorful than in London, Paris, Buenos Aires, or New York. News of the day—or the minute—rolled off the presses in every political persuasion from the hundred dailies and weeklies that were published there in a babel of languages, making Berlin the liveliest, most densely concentrated center of journalism in all Europe.

Berlin’s boosters were too focused on the future to give more than a backward glance to such slums and laborers’ districts as Wedding or to the workers’ children, like Leni, growing up in them. Civic do-gooders nodded dutifully as Kaiser Wilhelm II reminded them of “the duty to offer to the toiling classes the possibility of elevating themselves to the beautiful.” One had only to point inferiors in the direction of the Hohenzollern Palace, the Tiergarten, the Victory Column, the broad canals and their 957 bridges (more than in Venice), the Pergamon Museum with its antiquities, the Reichstag with its “To the German People” promise carved in stone beneath its sheltering dome of steel and glass; or to the glittering theaters, operas, and hotels, the promenade streets such as tree-canopied Unter den Linden or the racier Kurfürstendamm (Bismarck’s answer to the Champs-Élysées) lined with shops and sidewalk cafés. If the toiling class infrequently abandoned the factory floors for tours of the more elegant venues of imperial Berlin, the kaiser graciously imparted his notions of art and the beautiful to them. “An art which transgresses the laws and barriers outlined by Me,” he explained, “ceases to be an art.” This rang with reassuring certainty to the aesthetically insecure and was a viewpoint that a later leader—a onetime painter of picture postcards and aspiring architect—would echo and that millions would accept with awed docility.

No city in Europe made such a cult of modernity. Berlin was rushing at the turn of the century to make up in future what it lacked in past, while custodians of nostalgia mourned “a vanished Arcadia” that had never truly been. Velocity, anonymity, and the cheek-by-jowl juxtaposition of promise and peril inspired songs, paintings, novels, plays, and—already flickering silently when Leni was born—films. Most of these works inspired awe and alienation, too, as ordinary Berliners wondered uneasily where all this urban energy would lead. Ambivalence would find disturbing graphic expression in the 1920s, but prophetic, ominous visions of city life that were dubbed “degenerate” from the start began appearing in the teens from such painters as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Emil Nolde, and Ludwig Meidner, who labeled his urban paintings “apocalyptic landscapes.”

Berlin-Wedding had scant time for art or musings on modernity. It was a dense warren of factories, foundries, and labor. It was blocks of tenements—called Mietskaserne, rent barracks—crowding blue-collar families into one- or two-room flats stacked five or six stories high around sunless courtyards where life was harsh and suicide a daily occurrence. “Tenement sickness” was shorthand for tuberculosis and rickets in Berlin, where the infant mortality rate was almost 20 percent when the nineteenth century ended and more than double that in Wedding, where it reached a high of 42 percent just after Leni was delivered there.

Wedding was poor but not without altruism and aspiration. Its mean streets offered shelter to the homeless in a spartan doss-house, and there was a small pond for ice-skating. Someone in 1905 rented out part of a courtyard shed as a photographer’s studio, and it wasn’t long before one-reel movies were being shot there. In 1912, Wedding established Berlin’s first crematorium to compensate for the scarcity and cost of open burial ground. Children played in courtyards; geraniums grew on windowsills; music and love got made; and by 1918, nearly 40 percent of all Berliners lived in tenement districts like it. We see their faces in the etchings and prints of Käthe Kollwitz; their bawdy, earthy pleasures titillate still in the sketches of Heinrich Zille, the poetic folk satirist and painter who knew them best and once observed that you can kill a man with his lodgings as well as you can with an ax.

“I hated the class system,” Leni Riefenstahl confided to a friend. She was turning ninety then, living in a sheltered lakeside villa in Bavaria, distant enough in every way from Wedding to give perspective on her birthplace, a basic tenement flat in the two-block-long Prinz-Eugen-Strasse. The rooms were first lodgings for first-time parents who were almost newlyweds, married in a civil ceremony on April 5, 1902, nearly five months before their daughter saw first light in August.

Leni’s father, Alfred Theodor Paul Riefenstahl, was not yet twenty-four when she was born. He was one of three boys and a girl born to Gustav and Amalie (née Lehmann) Riefenstahl in 1878 in the rural Brandenburg district surrounding Berlin. His father had been a blacksmith like his father before him, but Alfred—blond and burly and wearing an upturned Kaiser Wilhelm mustache—had been drawn to Berlin by economic opportunity. He styled himself “salesman” on documents, but in fact he was a plumber. He would in time build his own sanitation and ventilation business as domestic plumbing became standard: niceties turned into necessities, and a plumber into an entrepreneur.

Leni’s mother, Bertha Ida Scherlach Riefenstahl, was almost twenty-two when her daughter was born. Bertha was a willowy beauty with dark eyes, curly dark hair, and a determined jawline, all of which she passed on to her only daughter, who was born cross-eyed. Bertha herself was the eighteenth child of a mother who died giving birth to her in Wloclawek (now in Poland) on October 9, 1880. Shortly after Bertha’s mother died, her father—Leni’s carpenter grandfather—married his children’s nanny and fathered three more children, for a total of twenty-one.

There is a mystery here, one that might amount only to a niggling biographical puzzle were it not a hint of the shifting images of the past that Leni would manipulate as times changed and perspectives with them. Her background unavoidably aroused curiosity in the 1930s among powerful figures of the Third Reich as she rose to prominence among them. Rumors that she was Jewish—or partly so—gained currency in this period and traced an alleged line of Jewish descent through Bertha. Once aired, the rumors gained wide circulation in the European and American press during the early years of the Third Reich, though the allegations were never proved and were officially repudiated by the ultimate Third Reich authority, the Führer himself. Leni brushed the subject aside then and later as the poisoned residue of a malicious campaign orchestrated against her by Nazi propaganda minister Dr. Joseph Goebbels.

While some of the rumors were almost certainly inspired by Goebbels or others jealous of her position and privileges in the 1930s, not all of them were. Some of Leni’s closest friends and colleagues, including Dr. Arnold Fanck, the film director credited with Leni’s discovery, believed that Bertha was Jewish. As Leni’s onetime mentor and lover—and later a Nazi Party member—Fanck’s objectivity and veracity are not beyond challenge. Less equivocal is the testimony of art director Isabella Ploberger, who worked and lived with Leni and Bertha during World War II and took for granted that Bertha—“a lovely person, a fine person”—was Jewish. Ploberger believed that Goebbels knew, which accounted for his animosity.

There are documents, to be sure. Chief among them is Leni’s “Proof of Descent” (“Abstammungs-Nachweis”), the genealogical record of ancestry she prepared and submitted to the Reich’s film office in 1933 to validate Aryan descent, necessary to work in the German film industry. This document has long been available but never fully scrutinized, not even by the Nazis for whom it was prepared. Bertha is inscribed there as the child of the carpenter Karl Ludwig Friedrich Scherlach (born 1842) and Ottilie Auguste Scherlach (née Boia), born out of wedlock on January 24, 1863, to Friederika Boia and an unknown father. Though Ottilie Boia and Karl Scherlach are said to have married in the Silesian town of Woldenburg (Dobiegniew in modern Poland), no record of the marriage is known to exist, and their union may have been by common law. But what has gone unnoticed and unremarked is that Ottilie Boia could not possibly have been Bertha’s mother. Born in 1863, she could not have given birth to seventeen children before delivering Bertha in 1880. Ottilie was almost certainly the nanny that Leni’s carpenter grandfather married after his first wife died in delivering Bertha, the birth mother who became a nonperson in the genealogy Leni tendered to the Third Reich. As for Ottilie, she lived out her days as Bertha’s stepmother and Leni’s stepgrandmother in a modest flat in Charlottenburg, the comfortable Berlin suburb where the adolescent Leni ran to her for strudel and sympathy when Alfred Riefenstahl’s strict discipline became intolerable.

Third Reich genealogies required declaration of religion as well as race, and Leni’s states that her forebears were Protestant. They appear not to have been devout. Since 1850, every birth, including Leni’s, was recorded at a registry office rather than at a church after a christening (though Leni was confirmed as Protestant in a Berlin church at fifteen).

The city and culture in which Leni grew up were famously cosmopolitan; Jewish conversion to Christianity and cultural assimilation were commonplace, though racial identity, rather than religious, would be the Nazis’ standard when theirs became the only one that mattered. No known documents fill the gap in Leni’s ancestry, but the substitution of Bertha’s stepmother for her birth mother on a Third Reich genealogical document is hard to fathom without considering a motive touching on race, since defining race was the point of the exercise. What is not speculative is Leni’s ability to define and redefine her past as circumstance or occasion required. As for Bertha, Leni “loved her to distraction” until she died in 1965 at the age of eighty-four.

Alfred Riefenstahl inspired different emotions. He was a striver: rigid, efficient, conservative, and Leni’s rival for Bertha's attention. His business depended on Berlin, though he felt ill at ease there with his provincial background and views of family life, especially after Leni’s only sibling, a brother named Heinz, was born on March 5, 1906. Alfred’s burgeoning business allowed him to move the family to a larger flat in Berlin-Neukölln just before Heinz was born and Leni began school. The old neighborhood and the new were similar (both would be centers of Communist agitation after 1918), so it came as a relief when the family could afford weekend excursions to a lakeside village about an hour southwest of Berlin by suburban rail.

Zeuthen was idyllic, green, and distanced Leni and little Heinz from the city’s dangers. It was tranquil enough for hiking, swimming, and languidly watching clouds roll by. The cottage the family rented—and would eventually acquire—was a short walk through the woods to the railway line to Berlin and just across the lake from the Gasthaus run by Bertha’s older sister Olga, who had alerted them to the area in the first place.

As a child, Leni was contentedly solitary except for her brother, perhaps a trait acquired because the family moved so often. After the apartments in Wedding and Neukölln and the weekend cottage at Zeuthen, there would be other flats in Berlin in the Goltzstrasse and in the Yorckstrasse, nearer the center of the city and her father’s business. But she may have been solitary by choice because she saw herself as special and precocious and needed no supporting cast but Heinz and no audience but the indulgent Bertha, “always my best friend.”

She began reading at an early age, she tells us, and started writing poetry and plays at the age of five after an excursion to the theater to see a performance of Snow White. Though Alfred preferred bowling or hunting with friends, he now and then treated his family to a show, stoutly impervious to the stage magic that would become a “driving force” for his impressionable daughter and remained one for his wife.

Bertha had dreamed as a girl of going on the stage and may actually have done so. A photograph taken before her marriage shows her dressed in the kind of dashing finery a Floradora girl might have worn: a short-sleeved, knee-length dress trimmed in garlands of flowers repeated in her hat and on the open fan in her right hand, cocked saucily on her hip. She told Leni that she had prayed while carrying her, “Dear God, give me a beautiful daughter who will become a famous actress.” The seed planted, grew. What young girl could resist thinking herself the answer to a prayer?

“I dreamed my dreams,” Leni said, creating meadowland theatrics in which she played the leading role and the obliging Heinz became her willing prop. Like her poems and daily life, her plays excluded companionship and outsiders. “I allowed no people into my verses, only trees, birds and even insects.”

As she entered adolescence, she fantasized becoming a nun, but the cloister sounded confining and self-denial dreary. News reports of aviation exploits during the Great War excited images of adventure and daring. They also inspired her to imagine an entire airline industry on paper, scheduling flights between European cities and even calculating the price of tickets, as if emulating Alfred’s administration of his plumbing business. “There was in me some organizational talent struggling to emerge,” she remembered later, an aptitude that would prove indispensable when competing in the real world as a woman in a man’s universe.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Brilliant. . . . It’s difficult to overpraise Bach’s efforts. . . . A compulsively readable and scrupulously crafted work . . . . [Bach created] an almost novelistically compelling narrative of a life endlessly obfuscated by lies.”

—The Los Angeles Times Book Review

“Energetic . . . Serves as [a] much needed corrective to all the spin, evasions and distortions of the record purveyed by Riefenstahl.”

—The New York Times

“Fascinating. . . . The definitive new biography from Steven Bach should silence any lingering Riefenstahl apologists. . . . [He] bravely sorts through the mountain of falsehoods.” —Film Comment

“Fascinating. . . . Leni is a cautionary tale about an artist whose prodigious determination and ambition seem to have been unmediated by the slightest influence of conscience, soul, or heart.”

—O, The Oprah Magazine

—The Los Angeles Times Book Review

“Energetic . . . Serves as [a] much needed corrective to all the spin, evasions and distortions of the record purveyed by Riefenstahl.”

—The New York Times

“Fascinating. . . . The definitive new biography from Steven Bach should silence any lingering Riefenstahl apologists. . . . [He] bravely sorts through the mountain of falsehoods.” —Film Comment

“Fascinating. . . . Leni is a cautionary tale about an artist whose prodigious determination and ambition seem to have been unmediated by the slightest influence of conscience, soul, or heart.”

—O, The Oprah Magazine