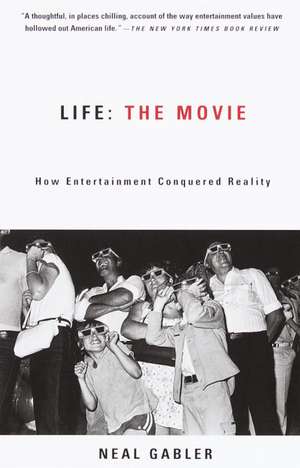

Life the Movie: How Entertainment Conquered Reality

Autor Neal Gableren Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 ian 2000

From one of America's most original cultural critics and the author of Winchell, the story of how our bottomless appetite for novelty, gossip, glamour, and melodrama has turned everything of importance-from news and politics to religion and high culture-into one vast public entertainment.

Neal Gabler calls them "lifies," those blockbusters written in the medium of life that dominate the media and the national conversation for weeks, months, even years: the death of Princess Diana, the trial of O.J. Simpson, Kenneth Starr vs. William Jefferson Clinton. Real Life as Entertainment is hardly a new phenomenon, but the movies, and now the new information technologies, have so accelerated it that it is now the reigning popular art form. How this came to pass, and just what it means for our culture and our personal lives, is the subject of this witty, concerned, and sometimes eye-opening book.

Preț: 115.65 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 173

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.13€ • 24.03$ • 18.59£

22.13€ • 24.03$ • 18.59£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-15 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375706530

ISBN-10: 0375706534

Pagini: 320

Dimensiuni: 132 x 201 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Ediția:Vintage Books.

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 0375706534

Pagini: 320

Dimensiuni: 132 x 201 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Ediția:Vintage Books.

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

Neal Gabler lives in Amagansett, New York.

Extras

Perhaps the most difficult adjustments to the imperatives of entertainment were those undergone by the arts which had, by definition, been arrayed against entertainment and had denied its sensationalist aesthetic. These had tried to hold the line even as everything else seemed to be succumbing around them, but not even art could finally resist the siren call of show business. The arts were forced either to surrender or to be marginalized to the point where they would cease to matter to any but a handful of devotees.

In literature the erosion of will began early. Some critics blamed paperback books for driving publishing into the arms of entertainment, seeing them, in effect, as the television of literature; they made books available, but they also cheapened them. One publisher, complaining about sensational paperback covers, opined, "The contents of the book . . . were relatively unimportant. What mattered was that its lurid exterior should ambush the customer." Others traced the decline even further back to the rise of magazine serialization as a major source of book revenue and the need for books to adapt themselves to this method of distribution, which entailed bold characters, strong plots, cliffhangers and other sensationalist appurtenances.

Still others saw the decline of serious literature in direct proportion to the rise of commerce in publishing. When the Book-of-the-Month Club, itself a commercial institution dedicated to selling books rather than promoting literature, eased out its editor in chief in 1996 and transferred his duties to the head of marketing, a former club juror, Brad Leithauser, dejectedly said they could just as easily be selling kitchen supplies now. It was an increasingly common plaint among writers that books had become another commodity to be marketed, but the blame on commercialism was misplaced. Since no one expected publishing to be an eleemosynary institution, the problem wasn't commercialism per se; it was the kinds of books that commerce demanded. What empowered the forces of marketing was entertainment because quite simply, entertaining books were more likely to sell than nonentertaining ones, or more accurately, books that could become part of an entertainment process were more likely to sell.

In a way the real entertainment hurdle for literature, even trashy popular literature, was the fact of the word. Words, as Neil Postman has written, demanded much more effort than visuals, and even if one were to expend that effort, there were obvious limitations to the sensation generated by words compared with the seemingly limitless sensation generated by the visuals and sounds of the movies, television and computers. None of this was lost on publishers. Just as newspapers realized their insufficiency versus television news, so publishers realized their insufficiency versus the entertainment competition, and they sought to do something about it.

What publishers discovered was that given the right circumstances, a book was ultimately incidental to its own sales. It was yet another macguffin for a larger show. What publishing houses were really selling was a phenomenon--something the media would flog the way media flogged any Hollywood blockbuster. The object was to get people talking about a book, get them feeling that they had missed something if they didn't know about it, even though they were responding not to the book itself, which few of then probably had read or would read, but rather to the frenzy whipped up around the book--a controversy or novel feature or eye-catching angle like a seven-figure advance to the author or a big-money sale of the film rights. The frenzy assumed a life of its own even as the alleged object of the frenzy kept receding further and further into the background. The novelist David Foster Wallace, bemused when the media began championing his immense novel Infinite Jest and making Wallace himself a literary star, called this the "excitement about the excitement." It was one of the principal marketing tools for anything in the Republic of Entertainment.

As far as literature went, most of the initial excitement was stirred not by the book but by its author, whose life movie would promote the book the way Olympic athletes' life movies promoted the Olympics for NBC. The tradition actually stretched back at least as far as Byron, who was canny enough to cultivate a bohemian persona as the Romantic poet and then actively exploit it. As Dwight Macdonald described it, "Byron's reputation was different from that of Chaucer, Spenser, Shakespeare, Milton, Dryden and Pope because it was based on the man--on what the public conceived to be the man--rather than on his work. His poems were taken not as artistic objects in themselves but as expressions of their creator's personality."

Walt Whitman did the same and to the same effect. He wanted to be seen as a character whose personality would advertise his poetry. A friend once described him as a "poseur of truly colossal proportions, one to whom playing a part had long before become so habitual that he ceased to be conscious that he was doing it." In fact, the idea that celebrity could create a best-seller more easily than a best-seller could create celebrity was enough of a commonplace by the end of the nineteenth century that the protagonist of New Grub Street, an 1891 novel, could say, "If I am an unknown man, and publish a wonderful book, it will make its way very slowly, or not at all. If I become a known man, publish that very same book, its praise will echo over both hemispheres "

However true it was then, it became even truer in the age of mass media. No one, though, seemed to have as ready a grasp of this as Ernest Hemingway, who was actually compared to Byron for his flagrant self-promotion. Just as thoroughly as any fictional character he created in his novels, Hemingway created a persona for himself and authored a life movie in which he could star on the screens of the media. This was Hemingway the artist roughneck, expatriate war hero, bullfight lover, big-game hunter, deep-sea fisherman, world-class drinker, womanizer, brawler--a man so outsized that he dwarfed the writer and his books even though this movie was the main reason anyone but litterateurs was likely to pay his books any heed. Critic Edmund Wilson churlishly called this persona "the Hemingway of the handsome photographs with the sportsman's tan and the outdoor grin, with the ominous resemblance to Clark Gable, who poses with giant marlin which he has just hauled off Key West," as opposed to Hemingway the writer.

Of course Hemingway knew the value of all this, and though critics continued to lament that he had sacrificed his art on the altar of celebrity or that he was, as Leo Braudy put it, "the prime case of someone fatally caught between his genius and his publicity," he realized that there might have been very little art if it weren't for the celebrity--at least very little art that anyone would buy, much less read. As he metamorphosed into "Papa Hemingway," the grizzled macho icon with his beard stubble and peak cap, he became more popular than ever and even gained a certain immunity from the critics, who now routinely disparaged his work. The public who defended him didn't really care whether he was a good writer. They cared that he was a bold personality--a movie's idea of a good writer.

In the end, Hemingway would be one of the most influential writers of the twentieth century, but it was not as the proponent of lean literary modernism; it was as the proponent of literary celebrity. Where he led, virtually every writer trying to make his mark followed. "The way to save your work and reach more readers is to advertise yourself, steal your own favorite page out of Hemingway's unwritten Notes from Papa on How the Working Novelist Can Get Ahead," Norman Mailer wrote in Advertisements for Myself, thus acknowledging his debt to Hemingway while also granting that he himself had a "changeable personality, a sullen disposition, and a calculating mind" that would seem to disqualify him from celebrity. (Of course, far from being disqualified, Mailer turned these very qualities into his own salable persona.)

Still, Hemingway and Mailer had talent, and their personas as brawling artists ultimately depended upon it. A more impressive feat was to create a persona so entertaining that there didn't have to be any talent. Editor Michael Korda credited writer Jacqueline Susann with this advance. Having emerged from public relations--Susann's husband, Irving Mansfield, was an old PR man--she hawked her books by hawking herself as a celebrity, though she had done nothing to earn that status. "When we expressed anxiety about the manuscript," Korda wrote in a reminiscence of Susann, "Irving told us that it was Jackie (and the example of 'Valley [of the Dolls],' then approaching ten million copies sold) that he was selling, and not, as he put it indignantly, 'a goddam pile of paper.'" His point was that the book was absolutely irrelevant once the name was on the cover.

It was a relatively small step from this to designer publishing, in which the author's name, like a fashion designer's label, sold the book even if the author hadn't written the book. This in fact was what technothriller author Tom Clancy achieved. In 1995 Clancy signed to publish a line of paperback thrillers targeted at teenagers, the first of which was to be titled Tom Clancy's Net Force. Despite the possessive case, however, Clancy wasn't necessarily going to write the story. As the New York Times put it in its announcement of the deal, his role would be to "oversee the book's production"--in the event, the byline read "created by Tom Clancy"--which gave the author an entirely new function. He was no longer a writer; he was an imprimatur.

With all this effort devoted to creating personalities who could sell books, the next logical step was to drop the middlemen--that is, writers--entirely and go directly to celebrities themselves, as publishers increasingly did through the 1980s and 1990s. Actors and actresses, singers, comedians, war heroes, anchormen and protagonists of scandals signed huge publishing contracts clearly not because anyone expected them to produce great books but because they carried ready-made entertainment value from other media which they could vest in this one. They were, in show business parlance, "crossover artists."

As it turned out, it was no guarantee. The trouble with celebrity as a sales device was that it was volatile, as Random House discovered after giving aging television-soap-opera diva Joan Collins $4 million to write a novel. Collins, however, delivered that the publisher deemed an unacceptable manuscript, and Random House sued to recover $1.2 million of the advance it had paid. Collins's editor, Joni Evans, testified that the novel was "very primitive, very much off base.... it was jumbled and disjointed"--as if she had been expecting Collins to submit a real book and not just put her name on the jacket. Collins told reporters afterwards, "They were begging for me!" and quoted Evans as having told agent Irving "Swifty" Lazar, "I want Joan Collins in my stable so much I can taste it!" But that was when Joan Collins was still a marketable name. By the time she submitted her manuscript, her star had fallen, and from the perspective of some outsiders at least, Random House seemed to be placed in the uncomfortable position of rejecting her for her decline. Or to put it another way, the book itself seemed to become relevant only when Collins wasn't.

With publishers essentially selling so many books on the backs of their authors' lives because these were the only things that could trigger the conventional media's interest, it almost became a requirement that noncelebrities have great life stories or be condemned to midlist, the Siberia of publishing. Even a dense and difficult literary novel like Salman Rushdie's The Satanic Verses became a best-seller when Iran's Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini issued a fatwa, or religious edict, imposing a death sentence on the author for allegedly having insulted the Muslim faith in the book. The fatwa thrust Rushdie into a terrifying life movie and forced him into hiding, but it also gave him a name recognition that very few literary novelists could possibly hope to match. When he appeared publicly in New York to promote a new novel, the cognoscenti showed up in force as they never would have had Rushdie been just an author rather than the celebrity star of his very own thriller. Columnist Frank Rich called the display "fatwa chic."

But Rushdie, a serious novelist, was simply the most glaring example of a publishing industry in hostage to entertainment, an industry in which authors' own stories superseded their books. Poet Ted Hughes's Birthday Letters became a best-seller because the poems addressed the suicide of his wife Sylvia Plath. A slender volume of verse titled Ants on the Melon by Virginia Hamilton Adair, an eighty-three-year-old blind woman who had gone largely unpublished, made Adair a minor celebrity and won her a New Yorker profile, though the poet J.D. McClatchy, unimpressed by the quality of the poetry, said, "Her story seems to be the story, not the work," which could also have been said about so many of the new literary phenomena. Even Adair herself agreed: "I think part of it is this old nut, a character."

Or there was Michael Palmer, the doctor who, inspired by the example of medical suspense novelist Robin Cook, decided to try his hand at a medical thriller. When he was about to embark on his book tour, however, he realized he wasn't getting what he called high-profile bookings. So Palmer decided to reveal that he was a recovering alcoholic and Demerol addict and was now helping other, similarly afflicted physicians. His publicists beamed over the disclosure, knowing it would generate press. Palmer's addictions thus became what he himself called a marketing device.

Slightly more savvy writers decided that if they were going to make their lives their marketing tools, they might as well make the life the book too. In part this may explain the craze for literary confessions in which writers divulge their deepest and occasionally dirtiest secrets--the autobiographical equivalent to the entertainingly lurid biographies dedicated to detailing a subject's pathologies. No matter how high-minded their professed motives, one suspects these memoirists also know the entertainment value of their tales: a poet who is a sex addict and child molester, a mopey young woman who is committed to a mental institution and another who battles anorexia, a young novelist addicted to anxiety inhibitors, another attractive young novelist who had an incestuous relationship with her father. Needless to say, plots like these make every bit as good entertainment as similar stories in the supermarket tabloids--which is to say that while confession may be good for the soul, it is also good for book sales.

But the final surrender of literature to entertainment may have come with the discovery that a book needn't even be a vehicle for its author's life; it could be a vehicle for the author's photo. Publishers had long preferred writers who were telegenic and glib, able to hawk their books where it counted: on television. By the mid-1990s, however, there was a group of young author pinups--Paul Watkins, Douglas Coupland, Tim Willocks, movie star/novelist Ethan Hawke--whose basic selling point was their appearance. "He had a rock-star type aura that these young women project onto the author," was how a promotions director at the Waterstone bookstore in Boston described Coupland's reading there before a large audience. Playing off his aura, Tim Willocks's publisher enclosed a photo of the writer with an invitation to a promotional lunch. "He's definitely a cute author," a features editor at Mademoiselle enthused. "We're definitely biased toward cute guys."

Perhaps it was inevitable that with literature drawn into the entertainment vortex, it would also generate ancillary merchandise just as movies generated toys, clothing, books and other products. Robert James Waller, whose The Bridges of Madison County became the very paradigm of a publishing phenomenon, wound up issuing a compact disc of himself singing his own compositions inspired by his own novel. Following his trail, novelist Joyce Maynard released a compact disc of music to accompany her book Where Love Goes, Elizabeth Wurtzel planned to provide a CD soundtrack for the paperback edition of her memoir Prozac Nation, James Redfield's inspirational book The Celestine Prophecy spawned The Celestine Prophecy: A Musical Voyage and Warner Bros. signed self-help writer Deepak Chopra to a recording contract. "Each of Deepak's seven spiritual laws of success could be distilled into a song," explained a record executive. "Then the theme of each law could be distilled into a mantra."

Viewing these developments with concern, the critic Jack Miles predicted that publishing would eventually find itself divided between a very small audience of readers seeking knowledge and a much larger audience seeking entertainment--in effect, another sacralization of the sort that had divided culture in the late nineteenth century. "What is offered for everybody will be entertainment and entertainment only, and then only at a level that excludes nobody," Miles wrote. "What is offered as knowledge, by contrast, will be offered, usually not for everybody but rather for professionals who will 'consume' it as (and mostly at) work." Extrapolating from Miles's vision, one could even imagine a day when there would be for everyone what had already long existed in Hollywood: designated readers to summarize plots, so that no one would ever have to tax himself by reading more than a few pages, as Hollywood executives were never taxed.

But even these divisions were not as clean as Miles suggested, because entertainment could not be kept so easily at bay. Books that purported to be informational were increasingly invaded by entertainment, so that one had to make a new distinction between real or traditional information and entertainment in the form of information--what has been called faction. The latter was the sort of thing in which best-selling celebrity biographer Kitty Kelley specialized. When she revealed in her 1997 biography of the Windsors that the queen mother was artificially inseminated, to cite just one example of many, her evidence seemed to be that everyone knew the king's brother Edward was impotent, that impotency ran in the Windsor family and so that therefore the logical conclusion was the one she drew. It was certainly a stretch, bur Kelley could get away with it because she knew accuracy was of little consequence to her readers; entertainment was. The most important thing in the Republic of Entertainment was that the facts be provocative enough to provide a sensational show.

In literature the erosion of will began early. Some critics blamed paperback books for driving publishing into the arms of entertainment, seeing them, in effect, as the television of literature; they made books available, but they also cheapened them. One publisher, complaining about sensational paperback covers, opined, "The contents of the book . . . were relatively unimportant. What mattered was that its lurid exterior should ambush the customer." Others traced the decline even further back to the rise of magazine serialization as a major source of book revenue and the need for books to adapt themselves to this method of distribution, which entailed bold characters, strong plots, cliffhangers and other sensationalist appurtenances.

Still others saw the decline of serious literature in direct proportion to the rise of commerce in publishing. When the Book-of-the-Month Club, itself a commercial institution dedicated to selling books rather than promoting literature, eased out its editor in chief in 1996 and transferred his duties to the head of marketing, a former club juror, Brad Leithauser, dejectedly said they could just as easily be selling kitchen supplies now. It was an increasingly common plaint among writers that books had become another commodity to be marketed, but the blame on commercialism was misplaced. Since no one expected publishing to be an eleemosynary institution, the problem wasn't commercialism per se; it was the kinds of books that commerce demanded. What empowered the forces of marketing was entertainment because quite simply, entertaining books were more likely to sell than nonentertaining ones, or more accurately, books that could become part of an entertainment process were more likely to sell.

In a way the real entertainment hurdle for literature, even trashy popular literature, was the fact of the word. Words, as Neil Postman has written, demanded much more effort than visuals, and even if one were to expend that effort, there were obvious limitations to the sensation generated by words compared with the seemingly limitless sensation generated by the visuals and sounds of the movies, television and computers. None of this was lost on publishers. Just as newspapers realized their insufficiency versus television news, so publishers realized their insufficiency versus the entertainment competition, and they sought to do something about it.

What publishers discovered was that given the right circumstances, a book was ultimately incidental to its own sales. It was yet another macguffin for a larger show. What publishing houses were really selling was a phenomenon--something the media would flog the way media flogged any Hollywood blockbuster. The object was to get people talking about a book, get them feeling that they had missed something if they didn't know about it, even though they were responding not to the book itself, which few of then probably had read or would read, but rather to the frenzy whipped up around the book--a controversy or novel feature or eye-catching angle like a seven-figure advance to the author or a big-money sale of the film rights. The frenzy assumed a life of its own even as the alleged object of the frenzy kept receding further and further into the background. The novelist David Foster Wallace, bemused when the media began championing his immense novel Infinite Jest and making Wallace himself a literary star, called this the "excitement about the excitement." It was one of the principal marketing tools for anything in the Republic of Entertainment.

As far as literature went, most of the initial excitement was stirred not by the book but by its author, whose life movie would promote the book the way Olympic athletes' life movies promoted the Olympics for NBC. The tradition actually stretched back at least as far as Byron, who was canny enough to cultivate a bohemian persona as the Romantic poet and then actively exploit it. As Dwight Macdonald described it, "Byron's reputation was different from that of Chaucer, Spenser, Shakespeare, Milton, Dryden and Pope because it was based on the man--on what the public conceived to be the man--rather than on his work. His poems were taken not as artistic objects in themselves but as expressions of their creator's personality."

Walt Whitman did the same and to the same effect. He wanted to be seen as a character whose personality would advertise his poetry. A friend once described him as a "poseur of truly colossal proportions, one to whom playing a part had long before become so habitual that he ceased to be conscious that he was doing it." In fact, the idea that celebrity could create a best-seller more easily than a best-seller could create celebrity was enough of a commonplace by the end of the nineteenth century that the protagonist of New Grub Street, an 1891 novel, could say, "If I am an unknown man, and publish a wonderful book, it will make its way very slowly, or not at all. If I become a known man, publish that very same book, its praise will echo over both hemispheres "

However true it was then, it became even truer in the age of mass media. No one, though, seemed to have as ready a grasp of this as Ernest Hemingway, who was actually compared to Byron for his flagrant self-promotion. Just as thoroughly as any fictional character he created in his novels, Hemingway created a persona for himself and authored a life movie in which he could star on the screens of the media. This was Hemingway the artist roughneck, expatriate war hero, bullfight lover, big-game hunter, deep-sea fisherman, world-class drinker, womanizer, brawler--a man so outsized that he dwarfed the writer and his books even though this movie was the main reason anyone but litterateurs was likely to pay his books any heed. Critic Edmund Wilson churlishly called this persona "the Hemingway of the handsome photographs with the sportsman's tan and the outdoor grin, with the ominous resemblance to Clark Gable, who poses with giant marlin which he has just hauled off Key West," as opposed to Hemingway the writer.

Of course Hemingway knew the value of all this, and though critics continued to lament that he had sacrificed his art on the altar of celebrity or that he was, as Leo Braudy put it, "the prime case of someone fatally caught between his genius and his publicity," he realized that there might have been very little art if it weren't for the celebrity--at least very little art that anyone would buy, much less read. As he metamorphosed into "Papa Hemingway," the grizzled macho icon with his beard stubble and peak cap, he became more popular than ever and even gained a certain immunity from the critics, who now routinely disparaged his work. The public who defended him didn't really care whether he was a good writer. They cared that he was a bold personality--a movie's idea of a good writer.

In the end, Hemingway would be one of the most influential writers of the twentieth century, but it was not as the proponent of lean literary modernism; it was as the proponent of literary celebrity. Where he led, virtually every writer trying to make his mark followed. "The way to save your work and reach more readers is to advertise yourself, steal your own favorite page out of Hemingway's unwritten Notes from Papa on How the Working Novelist Can Get Ahead," Norman Mailer wrote in Advertisements for Myself, thus acknowledging his debt to Hemingway while also granting that he himself had a "changeable personality, a sullen disposition, and a calculating mind" that would seem to disqualify him from celebrity. (Of course, far from being disqualified, Mailer turned these very qualities into his own salable persona.)

Still, Hemingway and Mailer had talent, and their personas as brawling artists ultimately depended upon it. A more impressive feat was to create a persona so entertaining that there didn't have to be any talent. Editor Michael Korda credited writer Jacqueline Susann with this advance. Having emerged from public relations--Susann's husband, Irving Mansfield, was an old PR man--she hawked her books by hawking herself as a celebrity, though she had done nothing to earn that status. "When we expressed anxiety about the manuscript," Korda wrote in a reminiscence of Susann, "Irving told us that it was Jackie (and the example of 'Valley [of the Dolls],' then approaching ten million copies sold) that he was selling, and not, as he put it indignantly, 'a goddam pile of paper.'" His point was that the book was absolutely irrelevant once the name was on the cover.

It was a relatively small step from this to designer publishing, in which the author's name, like a fashion designer's label, sold the book even if the author hadn't written the book. This in fact was what technothriller author Tom Clancy achieved. In 1995 Clancy signed to publish a line of paperback thrillers targeted at teenagers, the first of which was to be titled Tom Clancy's Net Force. Despite the possessive case, however, Clancy wasn't necessarily going to write the story. As the New York Times put it in its announcement of the deal, his role would be to "oversee the book's production"--in the event, the byline read "created by Tom Clancy"--which gave the author an entirely new function. He was no longer a writer; he was an imprimatur.

With all this effort devoted to creating personalities who could sell books, the next logical step was to drop the middlemen--that is, writers--entirely and go directly to celebrities themselves, as publishers increasingly did through the 1980s and 1990s. Actors and actresses, singers, comedians, war heroes, anchormen and protagonists of scandals signed huge publishing contracts clearly not because anyone expected them to produce great books but because they carried ready-made entertainment value from other media which they could vest in this one. They were, in show business parlance, "crossover artists."

As it turned out, it was no guarantee. The trouble with celebrity as a sales device was that it was volatile, as Random House discovered after giving aging television-soap-opera diva Joan Collins $4 million to write a novel. Collins, however, delivered that the publisher deemed an unacceptable manuscript, and Random House sued to recover $1.2 million of the advance it had paid. Collins's editor, Joni Evans, testified that the novel was "very primitive, very much off base.... it was jumbled and disjointed"--as if she had been expecting Collins to submit a real book and not just put her name on the jacket. Collins told reporters afterwards, "They were begging for me!" and quoted Evans as having told agent Irving "Swifty" Lazar, "I want Joan Collins in my stable so much I can taste it!" But that was when Joan Collins was still a marketable name. By the time she submitted her manuscript, her star had fallen, and from the perspective of some outsiders at least, Random House seemed to be placed in the uncomfortable position of rejecting her for her decline. Or to put it another way, the book itself seemed to become relevant only when Collins wasn't.

With publishers essentially selling so many books on the backs of their authors' lives because these were the only things that could trigger the conventional media's interest, it almost became a requirement that noncelebrities have great life stories or be condemned to midlist, the Siberia of publishing. Even a dense and difficult literary novel like Salman Rushdie's The Satanic Verses became a best-seller when Iran's Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini issued a fatwa, or religious edict, imposing a death sentence on the author for allegedly having insulted the Muslim faith in the book. The fatwa thrust Rushdie into a terrifying life movie and forced him into hiding, but it also gave him a name recognition that very few literary novelists could possibly hope to match. When he appeared publicly in New York to promote a new novel, the cognoscenti showed up in force as they never would have had Rushdie been just an author rather than the celebrity star of his very own thriller. Columnist Frank Rich called the display "fatwa chic."

But Rushdie, a serious novelist, was simply the most glaring example of a publishing industry in hostage to entertainment, an industry in which authors' own stories superseded their books. Poet Ted Hughes's Birthday Letters became a best-seller because the poems addressed the suicide of his wife Sylvia Plath. A slender volume of verse titled Ants on the Melon by Virginia Hamilton Adair, an eighty-three-year-old blind woman who had gone largely unpublished, made Adair a minor celebrity and won her a New Yorker profile, though the poet J.D. McClatchy, unimpressed by the quality of the poetry, said, "Her story seems to be the story, not the work," which could also have been said about so many of the new literary phenomena. Even Adair herself agreed: "I think part of it is this old nut, a character."

Or there was Michael Palmer, the doctor who, inspired by the example of medical suspense novelist Robin Cook, decided to try his hand at a medical thriller. When he was about to embark on his book tour, however, he realized he wasn't getting what he called high-profile bookings. So Palmer decided to reveal that he was a recovering alcoholic and Demerol addict and was now helping other, similarly afflicted physicians. His publicists beamed over the disclosure, knowing it would generate press. Palmer's addictions thus became what he himself called a marketing device.

Slightly more savvy writers decided that if they were going to make their lives their marketing tools, they might as well make the life the book too. In part this may explain the craze for literary confessions in which writers divulge their deepest and occasionally dirtiest secrets--the autobiographical equivalent to the entertainingly lurid biographies dedicated to detailing a subject's pathologies. No matter how high-minded their professed motives, one suspects these memoirists also know the entertainment value of their tales: a poet who is a sex addict and child molester, a mopey young woman who is committed to a mental institution and another who battles anorexia, a young novelist addicted to anxiety inhibitors, another attractive young novelist who had an incestuous relationship with her father. Needless to say, plots like these make every bit as good entertainment as similar stories in the supermarket tabloids--which is to say that while confession may be good for the soul, it is also good for book sales.

But the final surrender of literature to entertainment may have come with the discovery that a book needn't even be a vehicle for its author's life; it could be a vehicle for the author's photo. Publishers had long preferred writers who were telegenic and glib, able to hawk their books where it counted: on television. By the mid-1990s, however, there was a group of young author pinups--Paul Watkins, Douglas Coupland, Tim Willocks, movie star/novelist Ethan Hawke--whose basic selling point was their appearance. "He had a rock-star type aura that these young women project onto the author," was how a promotions director at the Waterstone bookstore in Boston described Coupland's reading there before a large audience. Playing off his aura, Tim Willocks's publisher enclosed a photo of the writer with an invitation to a promotional lunch. "He's definitely a cute author," a features editor at Mademoiselle enthused. "We're definitely biased toward cute guys."

Perhaps it was inevitable that with literature drawn into the entertainment vortex, it would also generate ancillary merchandise just as movies generated toys, clothing, books and other products. Robert James Waller, whose The Bridges of Madison County became the very paradigm of a publishing phenomenon, wound up issuing a compact disc of himself singing his own compositions inspired by his own novel. Following his trail, novelist Joyce Maynard released a compact disc of music to accompany her book Where Love Goes, Elizabeth Wurtzel planned to provide a CD soundtrack for the paperback edition of her memoir Prozac Nation, James Redfield's inspirational book The Celestine Prophecy spawned The Celestine Prophecy: A Musical Voyage and Warner Bros. signed self-help writer Deepak Chopra to a recording contract. "Each of Deepak's seven spiritual laws of success could be distilled into a song," explained a record executive. "Then the theme of each law could be distilled into a mantra."

Viewing these developments with concern, the critic Jack Miles predicted that publishing would eventually find itself divided between a very small audience of readers seeking knowledge and a much larger audience seeking entertainment--in effect, another sacralization of the sort that had divided culture in the late nineteenth century. "What is offered for everybody will be entertainment and entertainment only, and then only at a level that excludes nobody," Miles wrote. "What is offered as knowledge, by contrast, will be offered, usually not for everybody but rather for professionals who will 'consume' it as (and mostly at) work." Extrapolating from Miles's vision, one could even imagine a day when there would be for everyone what had already long existed in Hollywood: designated readers to summarize plots, so that no one would ever have to tax himself by reading more than a few pages, as Hollywood executives were never taxed.

But even these divisions were not as clean as Miles suggested, because entertainment could not be kept so easily at bay. Books that purported to be informational were increasingly invaded by entertainment, so that one had to make a new distinction between real or traditional information and entertainment in the form of information--what has been called faction. The latter was the sort of thing in which best-selling celebrity biographer Kitty Kelley specialized. When she revealed in her 1997 biography of the Windsors that the queen mother was artificially inseminated, to cite just one example of many, her evidence seemed to be that everyone knew the king's brother Edward was impotent, that impotency ran in the Windsor family and so that therefore the logical conclusion was the one she drew. It was certainly a stretch, bur Kelley could get away with it because she knew accuracy was of little consequence to her readers; entertainment was. The most important thing in the Republic of Entertainment was that the facts be provocative enough to provide a sensational show.

Recenzii

"Mesmerizing.... [It] frames a discussion that seems absolutely vital right now." -The Atlantic Monthly

"[An] engagingly written, often hilarious and well-informed account of the ways in which entertainment creates a Moebius strip world of stories and images." -The San Diego Union-Tribune

"[An] engagingly written, often hilarious and well-informed account of the ways in which entertainment creates a Moebius strip world of stories and images." -The San Diego Union-Tribune

Descriere

"Real life as entertainment" is explored as one of America's most original cultural critics reveals how our bottomless appetite for novelty, gossip, and melodrama has turned everything of importance into one vast public entertainment.