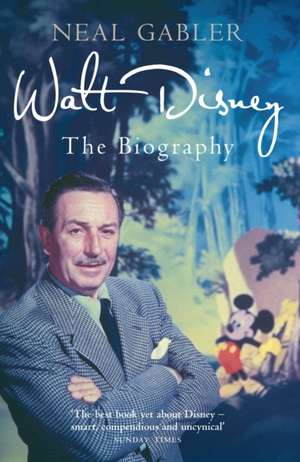

Walt Disney

Autor Neal Gableren Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mai 2011

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 98.03 lei 3-5 săpt. | +23.64 lei 7-11 zile |

| AURUM PRESS – 31 mai 2011 | 98.03 lei 3-5 săpt. | +23.64 lei 7-11 zile |

| Vintage Books USA – 30 sep 2007 | 169.10 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 98.03 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 147

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.76€ • 20.37$ • 15.76£

18.76€ • 20.37$ • 15.76£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-15 aprilie

Livrare express 18-22 martie pentru 33.63 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781845136741

ISBN-10: 1845136748

Pagini: 750

Ilustrații: black & white illustrations

Dimensiuni: 155 x 234 x 55 mm

Greutate: 0.57 kg

Editura: AURUM PRESS

ISBN-10: 1845136748

Pagini: 750

Ilustrații: black & white illustrations

Dimensiuni: 155 x 234 x 55 mm

Greutate: 0.57 kg

Editura: AURUM PRESS

Recenzii

“Mesmerizing. . . . There’s nothing Mickey Mouse about this terrific biography. . . . The definitive portrait of Walt Disney, the Dream-King.” —Washington Post Book World“Gabler’s restless eye invigorates each page. . . . Part of the author’s formidable achievement is to take the intricacies of Disney’s devoted artistry and intertwine them with [his] life.” —Los Angeles Times Book Review “Far outshines any previous Disney bio, both in scope and in specificity. The domestic details are revelatory. . . . Walt Disney is looking at us–seemingly for the first time.” —Entertainment Weekly “Illuminating. . . . Engrossing. . . . Gabler paints a vivid portrait.”—The New York Times Book Review

Notă biografică

Neal Gabler is the author of An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood, which won the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for history. His biography Winchell: Gossip, Power and the Culture of Celebrity was named best nonfiction book of the year by Time. He appears regularly on the media review program Fox News Watch, and writes often for The New York Times and the Los Angeles Times. He is currently a senior fellow at the Norman Lear Center for the Study of Entertainment and Society in the Annenberg School for Communications at the University of Southern California. He lives with his wife in Amagansett, New York.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter One

Escape

Elias Disney was a hard man. He worked hard, lived modestly, and worshiped devoutly. His son would say that he believed in “walking a straight and narrow path,” and he did, neither smoking nor drinking nor cursing nor carousing. The only diversion he allowed himself as a young man was playing the fiddle, and even then his upbringing was so strict that as a boy he would have to sneak off into the woods to practice. He spoke deliberately, rationing his words, and generally kept his emotions in check, save for his anger, which could erupt violently. He looked hard too, his body thin and taut, his arms ropy, his blue eyes and copper-colored hair offset by his stern visage—long and gaunt, sunken-cheeked and grim-mouthed. It was a pioneer’s weathered face—a no-nonsense face, the face of American Gothic.

But it was also a face etched with years of disappointment—disappointment that would shade and shape the life of his famous son, just as the Disney tenacity, drive, and pride would. The Disneys claimed to trace their lineage to the d’Isignys of Normandy, who had arrived in England with William the Conqueror and fought at the Battle of Hastings. During the English Restoration in the late seventeenth century, a branch of the family, Protestants, moved to Ireland, settling in County Kilkenny, where, Elias Disney would later boast, a Disney was “classed among the intellectual and well-to-do of his time and age.” But the Disneys were also ambitious and opportunistic, always searching for a better life. In July 1834, a full decade before the potato famine that would trigger mass migrations, Arundel Elias Disney, Elias Disney’s grandfather, sold his holdings, took his wife and two young children to Liverpool, and set out for America aboard the New Jersey with his older brother Robert and Robert’s wife and their two children.

They had intended to settle in America, but Arundel Elias did not stay there long. The next year he moved to the township of Goderich in the wilderness of southwestern Ontario, Canada, just off Lake Huron, and bought 149 acres along the Maitland River. In time Arundel Elias built the area’s first grist mill and a sawmill, farmed his land, and fathered sixteen children—eight boys and eight girls. In 1858 the eldest of them, twenty-five-year-old Kepple, who had come on the boat with his parents, married another Irish immigrant named Mary Richardson and moved just north of Goderich to Bluevale in Morris Township, where he bought 100 acres of land and built a small pine cabin. There his first son, Elias, was born on February 6, 1859.

Though he cleared the stony land and planted orchards, Kepple Disney was a Disney, with airs and dreams, and not the kind of man inclined to stay on a farm forever. He was tall, nearly six feet, and in his nephew’s words “as handsome a man as you would ever meet.” For a religious man he was also vain, sporting long black whiskers, the ends of which he liked to twirl, and jet-black oiled hair, always well coifed. And he was restless—a trait he would bequeath to his most famous descendant as he bequeathed his sense of self-importance. When oil was struck nearby in what came to be known as Oil Springs, Kepple rented out his farm, deposited his family with his wife’s sister, and joined a drilling crew. He was gone for two years, during which time the company struck no oil. He returned to Bluevale and his farm, only to be off again, this time to drill salt wells. He returned a year later, again without his fortune, built himself a new frame house on his land, and reluctantly resumed farming.

But that did not last either. Hearing of a gold strike in California, he set out in 1877 with eighteen-year-old Elias and his second-eldest son, Robert. They got only as far as Kansas when Kepple changed plans and purchased just over three hundred acres from the Union Pacific Railroad, which was trying to entice people to settle at division points along the train route it was laying through the state. (Since the Disneys were not American citizens, they could not acquire land under the Homestead Act.) The area in which the family settled, Ellis County in the northwestern quadrant of Kansas about halfway across the state, was frontier and rough. Indian massacres were fresh in memory, and the Disneys themselves waited out one Indian scare by stationing themselves all night at their windows with guns. Crime was rampant too. One visitor called the county seat, Hays, the “Sodom of the Plains.”

The climate turned out to be as inhospitable as the inhabitants—dry and bitter cold. At times it was so difficult to farm that the men would join the railroad crews while their wives scavenged for buffalo bones to sell to fertilizer manufacturers. Most of those who stayed on the land turned to livestock since the fields rippled with yellow buffalo grass on which sheep and cows could graze. Farming there either broke men or hardened them, as Elias would be hardened, but being as opportunistic as his Disney forebears, he had no more interest in farming than his father had. He wanted escape.

Father and son now set their sights on Florida. The winter of 1885–86 had been especially brutal in Ellis. Will Disney, Kepple’s youngest son, remembered the snow drifting into ten-to-twelve-foot banks, forcing the settlers from the wagon trains heading west to camp in the schoolhouse for six weeks until the weather broke. The snow was so deep that the train tracks were cleared only when six engines were hitched to a dead locomotive with a snowplow and made run after run at the drifts, inching forward and backing up, gradually nudging through. Kepple, tired of the cruel Kansas weather, decided to join a neighbor family on a reconnaissance trip to Lake County, in the middle of Florida, where the neighbors had relatives. Elias went with him.

For Elias, Florida held another inducement besides the promise of warm weather and new opportunities. The neighbor family they had accompanied, the Calls, had a sixteen-year-old daughter named Flora. The Calls, like the Disneys, were pioneers who nevertheless disdained the hardscrabble life. Their ancestors had arrived in America from England in 1636, settling first outside Boston and then moving to upstate New York. In 1825 Flora’s grandfather, Eber Call, reportedly to escape hostile Indians and bone-chilling cold, left with his wife and three children for Huron County in Ohio, where he cleared several acres and farmed. But Eber Call, like Kepple Disney, had higher aspirations. Two of his daughters became teachers, and his son, Charles, was graduated from Oberlin College in 1847 with high honors. After heading to California to find gold and then drifting through the West for several years, Charles wound up outside Des Moines, Iowa, where he met Henrietta Gross, a German immigrant. They married on September 9, 1855, and returned to his father’s house in Ohio. Charles became a teacher.

Exactly why at the age of fifty-six he decided to leave Ohio in January 1879, after roughly twenty years there and ten children, is a mystery, though a daughter later claimed it was because he was fearful that one of his eight girls might marry into a neighbor family with eight sons, none of whom were sober enough for the devout teacher. Why he chose to become a farmer is equally mysterious, and why he chose Ellis, Kansas, is more mysterious still. The rough-hewn frontier town was nothing like the tranquil Ohio village he had left, and it had little to offer save for cheap land. But Ellis proved no more hospitable to the Calls than it had to the Disneys. Within a year the family had begun to scatter. Flora, scarcely in her teens, was sent to normal school in Ellsworth to be trained as a teacher, and apparently roomed with Albertha Disney, Elias’s sister, though it is likely he had already taken notice of her since the families’ farms were only two miles from each other.

Within a few years the weather caught up to the Calls—probably the legendary storm of January 1886. In all likelihood it was the following autumn that they left for Florida by train with Elias and Kepple Disney as company. Kepple returned to Ellis shortly thereafter. Elias stayed on with the Calls. The area where they settled, in the middle of the state, was by one account “howling wilderness” at the time. Even so, after their Kansas experience the Calls found it “beautiful” and thought their new life there would be “promising.” It was known generally as Pine Island for its piney woods on the wet, high rolling land and for the rivers that isolated it, but it was dotted with new outposts. Elias settled in Acron, where there were only seven families; the Calls settled in adjoining Kismet. Charles cleared some acreage to raise oranges and took up teaching again in neighboring Norristown, while Flora became the teacher in Acron her first year and Paisley her second. Meanwhile Elias delivered mail from a horse-drawn buckboard and courted Flora.

Their marriage, at the Calls’ home in Kismet on New Year’s Day 1888, wedded the intrepid determination of the Disneys with the softer, more intellectual temper of the Calls—two strains of earthbound romanticism that would merge in their youngest son. The couple even looked the part, Elias’s flinty gauntness contrasting with Flora’s amiable roundness, as his age—he was nearly thirty at the time of the wedding—contrasted with the nineteen-year-old bride’s youth. Marriage, however, didn’t change his fortunes. He had bought an orange grove, but a freeze destroyed most of his crop, forcing him back into delivering the mail. In the meantime Charles Call had an accident while clearing some land of pines, never fully recovered, and died early in 1890. His death loosened the couple’s bond to Florida. “Elias was very much like his father; he couldn’t be contented very long in any one place,” Elias’s cousin, Peter Cantelon, observed. The Disney wanderlust and the need to escape would send Elias back north—this time to a nine-room house in Chicago.

He had been preceded to Chicago by someone who seemed just as blessed as Elias was cursed. Robert Disney, Elias’s younger brother by two-and-a-half years, was viewed by the family as the successful one. He was big and handsome—tall, broad, and fleshy where Elias was short, slim, and wiry, and he had an expansive, voluble, glad-handing manner to match his appearance. The “real dandy of the family,” his nephew would say. But if Robert Disney looked the very picture of a man of means, the image obscured the fact that he was actually a schemer with talents for convincing and cajoling that Elias could never hope to match. Six months after Elias married Flora, Robert had married a wealthy Boston girl named Margaret Rogers and embarked on his career of speculation in real estate, oil, and even gold mines—anything he could squeeze for a profit. He had come to Chicago in 1889 in anticipation of the 1893 Columbian Exposition, which would celebrate the four-hundredth anniversary of Columbus’s discovery of America, and had built a hotel there. Elias had also come for the promise of employment from the fair, but his dreams were humbler. Living in his brother’s shadow, he was hoping for work not as a magnate but as a carpenter, a skill he had apparently acquired while laboring on the railroad in his knockabout days.

The Disneys arrived in Chicago late in the spring of 1890, a few months after Charles Call’s death, with their infant son, Herbert, and with Flora pregnant again. Elias rented a one-story frame cottage at 3515 South Vernon on the city’s south side, an old mid-nineteenth-century farmhouse now isolated amid much more expensive residences; its chief recommendation was that it was only twenty blocks from the site of the exposition. Construction on the fair began early the next year, after Flora had given birth that December to a second son, Ray. The family enjoyed few extravagances. Elias earned only a dollar a day as a carpenter. But he was industrious and frugal, and by the fall he had saved enough to purchase a plot of land for $700 through his brother’s real estate connections. By the next year he had applied for a building permit at 1249 Tripp Avenue* to construct a two-story wooden cottage for his family, which the following June would add another son, Roy O. Disney.

Though it was set within the city, the area to which they moved the spring of 1893, in the northwestern section, was primitive. It had only two paved roads and had just begun to be platted for construction, which made it a propitious place for a carpenter. Elias contracted to help build homes, and one of his sons recalled that Flora too would go out to the sites and “hammer and saw planks with the men.” Still, by his wife’s estimate Elias averaged only seven dollars a week. But he was a Disney, and he had not surrendered his dreams. Using Robert’s contacts and leveraging his own house through mortgages, he began buying plots in the subdivision, designing residences with Flora’s help and then building them—small cottages for workingmen like himself. By the end of the decade he and a contracting associate had built at least two additional homes on the same street on which he lived—one of which he sold for $2,500 and the other of which he and his partner rented out for income. In effect, under Robert’s tutelage, Elias had become a real estate maven, albeit an extremely modest one.

But by this time, already in his forties, he had begun to place his hope less in success, which seemed hard-won and capricious, than in faith. Both the Disneys and the Calls had been deeply religious, and Elias and Flora’s social life in Chicago now orbited the nearby Congregational church, of which they were among the most devoted members. When the congregation decided to reorganize and then voted to erect a new building just two blocks from the Disneys’ home, Elias was named a trustee as well as a member of the building committee. By the time the new church, St. Paul’s, was dedicated in October 1900, the family was attending services not only on Sundays but during the week. Occasionally, when the minister was absent, Elias would even take the pulpit. “[H]e was a pretty good preacher,” Flora would remember. “[H]e did a lot of that at home, you know.”

From the Hardcover edition.

Escape

Elias Disney was a hard man. He worked hard, lived modestly, and worshiped devoutly. His son would say that he believed in “walking a straight and narrow path,” and he did, neither smoking nor drinking nor cursing nor carousing. The only diversion he allowed himself as a young man was playing the fiddle, and even then his upbringing was so strict that as a boy he would have to sneak off into the woods to practice. He spoke deliberately, rationing his words, and generally kept his emotions in check, save for his anger, which could erupt violently. He looked hard too, his body thin and taut, his arms ropy, his blue eyes and copper-colored hair offset by his stern visage—long and gaunt, sunken-cheeked and grim-mouthed. It was a pioneer’s weathered face—a no-nonsense face, the face of American Gothic.

But it was also a face etched with years of disappointment—disappointment that would shade and shape the life of his famous son, just as the Disney tenacity, drive, and pride would. The Disneys claimed to trace their lineage to the d’Isignys of Normandy, who had arrived in England with William the Conqueror and fought at the Battle of Hastings. During the English Restoration in the late seventeenth century, a branch of the family, Protestants, moved to Ireland, settling in County Kilkenny, where, Elias Disney would later boast, a Disney was “classed among the intellectual and well-to-do of his time and age.” But the Disneys were also ambitious and opportunistic, always searching for a better life. In July 1834, a full decade before the potato famine that would trigger mass migrations, Arundel Elias Disney, Elias Disney’s grandfather, sold his holdings, took his wife and two young children to Liverpool, and set out for America aboard the New Jersey with his older brother Robert and Robert’s wife and their two children.

They had intended to settle in America, but Arundel Elias did not stay there long. The next year he moved to the township of Goderich in the wilderness of southwestern Ontario, Canada, just off Lake Huron, and bought 149 acres along the Maitland River. In time Arundel Elias built the area’s first grist mill and a sawmill, farmed his land, and fathered sixteen children—eight boys and eight girls. In 1858 the eldest of them, twenty-five-year-old Kepple, who had come on the boat with his parents, married another Irish immigrant named Mary Richardson and moved just north of Goderich to Bluevale in Morris Township, where he bought 100 acres of land and built a small pine cabin. There his first son, Elias, was born on February 6, 1859.

Though he cleared the stony land and planted orchards, Kepple Disney was a Disney, with airs and dreams, and not the kind of man inclined to stay on a farm forever. He was tall, nearly six feet, and in his nephew’s words “as handsome a man as you would ever meet.” For a religious man he was also vain, sporting long black whiskers, the ends of which he liked to twirl, and jet-black oiled hair, always well coifed. And he was restless—a trait he would bequeath to his most famous descendant as he bequeathed his sense of self-importance. When oil was struck nearby in what came to be known as Oil Springs, Kepple rented out his farm, deposited his family with his wife’s sister, and joined a drilling crew. He was gone for two years, during which time the company struck no oil. He returned to Bluevale and his farm, only to be off again, this time to drill salt wells. He returned a year later, again without his fortune, built himself a new frame house on his land, and reluctantly resumed farming.

But that did not last either. Hearing of a gold strike in California, he set out in 1877 with eighteen-year-old Elias and his second-eldest son, Robert. They got only as far as Kansas when Kepple changed plans and purchased just over three hundred acres from the Union Pacific Railroad, which was trying to entice people to settle at division points along the train route it was laying through the state. (Since the Disneys were not American citizens, they could not acquire land under the Homestead Act.) The area in which the family settled, Ellis County in the northwestern quadrant of Kansas about halfway across the state, was frontier and rough. Indian massacres were fresh in memory, and the Disneys themselves waited out one Indian scare by stationing themselves all night at their windows with guns. Crime was rampant too. One visitor called the county seat, Hays, the “Sodom of the Plains.”

The climate turned out to be as inhospitable as the inhabitants—dry and bitter cold. At times it was so difficult to farm that the men would join the railroad crews while their wives scavenged for buffalo bones to sell to fertilizer manufacturers. Most of those who stayed on the land turned to livestock since the fields rippled with yellow buffalo grass on which sheep and cows could graze. Farming there either broke men or hardened them, as Elias would be hardened, but being as opportunistic as his Disney forebears, he had no more interest in farming than his father had. He wanted escape.

Father and son now set their sights on Florida. The winter of 1885–86 had been especially brutal in Ellis. Will Disney, Kepple’s youngest son, remembered the snow drifting into ten-to-twelve-foot banks, forcing the settlers from the wagon trains heading west to camp in the schoolhouse for six weeks until the weather broke. The snow was so deep that the train tracks were cleared only when six engines were hitched to a dead locomotive with a snowplow and made run after run at the drifts, inching forward and backing up, gradually nudging through. Kepple, tired of the cruel Kansas weather, decided to join a neighbor family on a reconnaissance trip to Lake County, in the middle of Florida, where the neighbors had relatives. Elias went with him.

For Elias, Florida held another inducement besides the promise of warm weather and new opportunities. The neighbor family they had accompanied, the Calls, had a sixteen-year-old daughter named Flora. The Calls, like the Disneys, were pioneers who nevertheless disdained the hardscrabble life. Their ancestors had arrived in America from England in 1636, settling first outside Boston and then moving to upstate New York. In 1825 Flora’s grandfather, Eber Call, reportedly to escape hostile Indians and bone-chilling cold, left with his wife and three children for Huron County in Ohio, where he cleared several acres and farmed. But Eber Call, like Kepple Disney, had higher aspirations. Two of his daughters became teachers, and his son, Charles, was graduated from Oberlin College in 1847 with high honors. After heading to California to find gold and then drifting through the West for several years, Charles wound up outside Des Moines, Iowa, where he met Henrietta Gross, a German immigrant. They married on September 9, 1855, and returned to his father’s house in Ohio. Charles became a teacher.

Exactly why at the age of fifty-six he decided to leave Ohio in January 1879, after roughly twenty years there and ten children, is a mystery, though a daughter later claimed it was because he was fearful that one of his eight girls might marry into a neighbor family with eight sons, none of whom were sober enough for the devout teacher. Why he chose to become a farmer is equally mysterious, and why he chose Ellis, Kansas, is more mysterious still. The rough-hewn frontier town was nothing like the tranquil Ohio village he had left, and it had little to offer save for cheap land. But Ellis proved no more hospitable to the Calls than it had to the Disneys. Within a year the family had begun to scatter. Flora, scarcely in her teens, was sent to normal school in Ellsworth to be trained as a teacher, and apparently roomed with Albertha Disney, Elias’s sister, though it is likely he had already taken notice of her since the families’ farms were only two miles from each other.

Within a few years the weather caught up to the Calls—probably the legendary storm of January 1886. In all likelihood it was the following autumn that they left for Florida by train with Elias and Kepple Disney as company. Kepple returned to Ellis shortly thereafter. Elias stayed on with the Calls. The area where they settled, in the middle of the state, was by one account “howling wilderness” at the time. Even so, after their Kansas experience the Calls found it “beautiful” and thought their new life there would be “promising.” It was known generally as Pine Island for its piney woods on the wet, high rolling land and for the rivers that isolated it, but it was dotted with new outposts. Elias settled in Acron, where there were only seven families; the Calls settled in adjoining Kismet. Charles cleared some acreage to raise oranges and took up teaching again in neighboring Norristown, while Flora became the teacher in Acron her first year and Paisley her second. Meanwhile Elias delivered mail from a horse-drawn buckboard and courted Flora.

Their marriage, at the Calls’ home in Kismet on New Year’s Day 1888, wedded the intrepid determination of the Disneys with the softer, more intellectual temper of the Calls—two strains of earthbound romanticism that would merge in their youngest son. The couple even looked the part, Elias’s flinty gauntness contrasting with Flora’s amiable roundness, as his age—he was nearly thirty at the time of the wedding—contrasted with the nineteen-year-old bride’s youth. Marriage, however, didn’t change his fortunes. He had bought an orange grove, but a freeze destroyed most of his crop, forcing him back into delivering the mail. In the meantime Charles Call had an accident while clearing some land of pines, never fully recovered, and died early in 1890. His death loosened the couple’s bond to Florida. “Elias was very much like his father; he couldn’t be contented very long in any one place,” Elias’s cousin, Peter Cantelon, observed. The Disney wanderlust and the need to escape would send Elias back north—this time to a nine-room house in Chicago.

He had been preceded to Chicago by someone who seemed just as blessed as Elias was cursed. Robert Disney, Elias’s younger brother by two-and-a-half years, was viewed by the family as the successful one. He was big and handsome—tall, broad, and fleshy where Elias was short, slim, and wiry, and he had an expansive, voluble, glad-handing manner to match his appearance. The “real dandy of the family,” his nephew would say. But if Robert Disney looked the very picture of a man of means, the image obscured the fact that he was actually a schemer with talents for convincing and cajoling that Elias could never hope to match. Six months after Elias married Flora, Robert had married a wealthy Boston girl named Margaret Rogers and embarked on his career of speculation in real estate, oil, and even gold mines—anything he could squeeze for a profit. He had come to Chicago in 1889 in anticipation of the 1893 Columbian Exposition, which would celebrate the four-hundredth anniversary of Columbus’s discovery of America, and had built a hotel there. Elias had also come for the promise of employment from the fair, but his dreams were humbler. Living in his brother’s shadow, he was hoping for work not as a magnate but as a carpenter, a skill he had apparently acquired while laboring on the railroad in his knockabout days.

The Disneys arrived in Chicago late in the spring of 1890, a few months after Charles Call’s death, with their infant son, Herbert, and with Flora pregnant again. Elias rented a one-story frame cottage at 3515 South Vernon on the city’s south side, an old mid-nineteenth-century farmhouse now isolated amid much more expensive residences; its chief recommendation was that it was only twenty blocks from the site of the exposition. Construction on the fair began early the next year, after Flora had given birth that December to a second son, Ray. The family enjoyed few extravagances. Elias earned only a dollar a day as a carpenter. But he was industrious and frugal, and by the fall he had saved enough to purchase a plot of land for $700 through his brother’s real estate connections. By the next year he had applied for a building permit at 1249 Tripp Avenue* to construct a two-story wooden cottage for his family, which the following June would add another son, Roy O. Disney.

Though it was set within the city, the area to which they moved the spring of 1893, in the northwestern section, was primitive. It had only two paved roads and had just begun to be platted for construction, which made it a propitious place for a carpenter. Elias contracted to help build homes, and one of his sons recalled that Flora too would go out to the sites and “hammer and saw planks with the men.” Still, by his wife’s estimate Elias averaged only seven dollars a week. But he was a Disney, and he had not surrendered his dreams. Using Robert’s contacts and leveraging his own house through mortgages, he began buying plots in the subdivision, designing residences with Flora’s help and then building them—small cottages for workingmen like himself. By the end of the decade he and a contracting associate had built at least two additional homes on the same street on which he lived—one of which he sold for $2,500 and the other of which he and his partner rented out for income. In effect, under Robert’s tutelage, Elias had become a real estate maven, albeit an extremely modest one.

But by this time, already in his forties, he had begun to place his hope less in success, which seemed hard-won and capricious, than in faith. Both the Disneys and the Calls had been deeply religious, and Elias and Flora’s social life in Chicago now orbited the nearby Congregational church, of which they were among the most devoted members. When the congregation decided to reorganize and then voted to erect a new building just two blocks from the Disneys’ home, Elias was named a trustee as well as a member of the building committee. By the time the new church, St. Paul’s, was dedicated in October 1900, the family was attending services not only on Sundays but during the week. Occasionally, when the minister was absent, Elias would even take the pulpit. “[H]e was a pretty good preacher,” Flora would remember. “[H]e did a lot of that at home, you know.”

From the Hardcover edition.