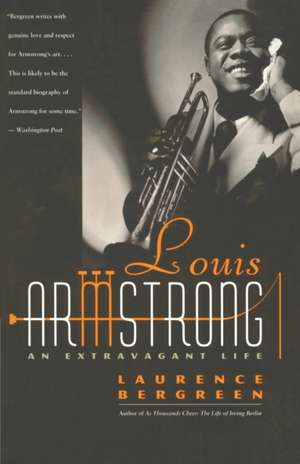

Louis Armstrong: An Extravagant Life

Autor Laurence Bergreenen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mai 1998

Born in 1901 to the sixteen-year-old daughter of a slave, he came of age among the prostitutes, pimps, and rag-and-bone merchants of New Orleans. He married four times and enjoyed countless romantic involvements in and around his marriages. A believer in marijuana for the head and laxatives for the bowels, he was also a prolific diarist and correspondent, a devoted friend to celebrities from Bing Crosby to Ella Fitzgerald, a perceptive social observer, and, in his later years, an international goodwill ambassador.

And, of course, he was a dazzling musician. From the bordellos and honky-tonks of Storyville--New Orleans's red light district--to the upscale nightclubs in Chicago, New York, and Hollywood, Armstrong's stunning playing, gravelly voice, and irrepressible personality captivated audiences and critics alike. Recognized and beloved wherever he went, he nonetheless managed to remain vigorously himself.

Now Laurence Bergreen's remarkable book brings to life the passionate, courageous, and charismatic figure who forever changed the face of American music.

Preț: 170.61 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 256

Preț estimativ în valută:

32.65€ • 33.88$ • 27.29£

32.65€ • 33.88$ • 27.29£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 22 februarie-08 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780767901567

ISBN-10: 0767901568

Pagini: 564

Dimensiuni: 140 x 213 x 36 mm

Greutate: 0.75 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0767901568

Pagini: 564

Dimensiuni: 140 x 213 x 36 mm

Greutate: 0.75 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

Recenzii

"Bergreen writes with genuine love and respect for Armstrong's art....This is likely to be the standard biography of Armstrong for some time."

--Washington Post

"A full-bodied portrait of the artist and the man that is far more interesting than his already colorful legend."

--USA Today

"No one has done a better job than Bergreen of making emotional sense of Armstrong's four marriages and uncounted affairs. . . . The fullest and frankest account of Armstrong to date."

--Boston Sunday Globe

"A meticulously researched, vibrant biography, which has the potential to become the definitive word on Armstrong's life and remarkable career."

--Variety

--Washington Post

"A full-bodied portrait of the artist and the man that is far more interesting than his already colorful legend."

--USA Today

"No one has done a better job than Bergreen of making emotional sense of Armstrong's four marriages and uncounted affairs. . . . The fullest and frankest account of Armstrong to date."

--Boston Sunday Globe

"A meticulously researched, vibrant biography, which has the potential to become the definitive word on Armstrong's life and remarkable career."

--Variety

Notă biografică

Laurence Bergreen was born in New York City and educated at Harvard University. He is the author of As Thousands Cheer: The Life of Irving Berlin (winner of the Ralph J. Gleason Music Book Award); James Agee: A Life; and Capone: The Man and the Era. A frequent contributor to Esquire, Newsweek, the New York Times, and other publications, he lives in New York City with his family.

Extras

In the beginning, he was a sound, and only a sound: a strange blend of happy cacophony and tormented caterwauling. Nothing like it had ever been heard before, not in New Orleans, where he was born in 1901, or Chicago or St. Louis, where he played as an emerging virtuoso cornetist, and certainly not in New York, where Duke Ellington said of his first exposure to that sound, "Nobody had ever heard anything like it, and his impact cannot be put into words." Nor had it ever been heard in Europe, or South America, or Africa, but everywhere it would be known as the sound of America.

With this sound, he established more popular songs than any other musician. The sound had two components. There was, initially, a cornet--and later a trumpet--that was more expressive than a mere instrument: sweet, stinging, lilting, cajoling, teasing, ebullient. And then there was his voice, the unforgettable voice that behaved like a huge instrument: growling, laughing, demented, soothing, fierce. The combination of the voice that sounded like an instrument and the instrument that sounded like a voice created the universally recognized persona of Satchmo. He looked and felt like a glowing lump of coal, hot and alive and capable of igniting everything around him. For him, music was a heightened form of existence, and he sang and he played as if it could never be loud enough, or last long enough, or go deep enough, or reach high enough. He believed there could never be enough music in the world, and he did his damnedest to fill the silence with all the stomping, roaring, screeching, sighing polyphony he could muster.

He was not just America's greatest musical performer, he was also a character of epic proportions: married four times, with countless romantic involvements in and around his marriages ("Take your shoes off, Lucy, and let's get juicy," he growls in "Baby, It's Cold Outside"); a lifelong believer in marijuana for the head and laxatives for the bowels; an accomplished storyteller who tossed off letters and memoirs with the same abandon he tossed off riffs; and an enthusiastic correspondent who as a young man turned to his typewriter to record his experiences and his glorious hard times, the record of a black man trying to make his way in twentieth-century America.

It would be pleasant to memorialize Louis this way, as a happy innocent, his life an unbroken arc from the streets, dance halls, and brothels of New Orleans to the nightclubs, vaudeville theaters, and concert halls of Chicago, and New York, and then on to the sound stages of Hollywood and all the other venues and cradles of popular culture from Scandinavia to Africa, where he is revered. It would be heartwarming to envision him effortlessly breaking "color barriers" everywhere he went, with audiences screaming, "Satchmo, Satchmo," as he smiled and blew his horn and wiped his perspiring brow with his spotless white handkerchief and sang "Ain't Misbehavin'" and growled a few words of filthy comic asides to the band, and then smiled again and eagerly pumped the valves on his gleaming trumpet, and raised it to his scarred yet indestructible chops, and blew his horn some more.

It would be convenient if his life were that simple, but of course it wasn't, not at all.

It was, in all externals, a wretched childhood, yet Louis was obsessed with it and returned to it throughout his maturity as the wellspring of his identity, of his music, of jazz itself. From the time he purchased his first typewriter in 1922, Louis tapped out his reminiscences, observations, dirty stories, bawdy puns and limericks, and most anything else that popped into his superheated mind. Sometimes he wrote in his hotel rooms, and sometimes he wrote between sets, in the dressing room of whatever nightclub or theater he happened to be performing in. He spent almost as much time pounding the keys of his typewriter as he did pumping the valves of his trumpet. And he told the same tales with each instrument, which only made sense, because in his mind, he was jazz; to prove his point, he titled the first chapter of his autobiography, "Jazz and I Get Born Together." He was driven to review and renew the sources of his inspiration whenever he could. The further his ambitions, accomplishments, and fame took him from his childhood, the more avidly he sought to return to it--to re-create it onstage night after night, to reminisce compulsively about it with friends, and to recapture it in an outpouring of letters and memoirs both published and unpublished, that spare nothing and relish every amusing, odd, or gruesome detail of his boyhood. His cherished memories preserve a vanished, and, to many, unknown way of life--that of poor black people in New Orleans in the early decades of this century.[fcmps]

Louis wrote as he spoke, in torrents of phrases linked by ellipses, as if he were writing an endless gossip column, the gossip of his life. He preferred to write on his stationery, in green ink on yellow paper, and when that was not available, on hotel stationery, even on the back of an envelope containing a letter inside. He distributed his confessional letters across the world to his correspondents, and some of them later appeared in popular magazines such as True, Esquire, and Ebony, which were willing to run his raw tales of his youth and sexual adventures pretty much as he wrote them. Many others have found their way into libraries and archives, and countless others languish in private hands. Eventually, in his early fifties, he summoned the confidence to write his autobiography, published under the title Satchmo: My Life in New Orleans. He wrote it by himself, without the aid of a ghostwriter, secretary, or amanuensis, and the book became a summation of all the letters he had ever written and stories he had ever told about the good old, bad old days in New Orleans.

The outcome of all this ceaseless literary activity, which neatly complemented his musical outpouring, was a kind of self-analysis, for his writing always returned to the same cluster of themes: how I became who I am; how my experiences, especially as a boy, have left indelible marks on me; and, implicitly, how I learned to turn adversity into happiness most of the time, and music all the time. Though confessional, his writing was never intended to be private. Except when he was intent on saving his energy for a performance, Louis was exceptionally gregarious--too gregarious to confine his writing to a diary, and too much of an exhibitionist not to tell everybody, if only for sheer shock value. Writing was for him a transactional process, a conversation with another person, and his conversation always came back to the same point: how the grim circumstances into which he had been born and raised in fact constituted a charmed life, the ideal childhood for a jazz musician.

Louis's consciousness was unique and all-encompassing. He held nothing back. People who knew him well invariably use the same word to describe him: "natural." He always said exactly what was on his mind, usually a mixture of music, sex, food, laxatives, and childhood memories. Even at the age of seventy, he boasted of his sexual prowess, and throughout his life he happily described who he had just gone to bed with, whether it was his wife or a girlfriend, and what they had done, and how he felt about it--usually delighted. He also reveled in his bowel movements. These were occasions for rejoicing, and he was not shy about sharing his enthusiasm for them with the world. His stationery, for instance, showed him sitting on a toilet, pants down around his ankles, grinning, glimpsed as if through a keyhole, with the legend underneath: SATCHMO SAYS: LEAVE IT ALL BEHIND YA! He urged his friends to take the strong laxative he used, Swiss Kriss, a herbal remedy sold by the physical culturist Gayelord Hauser, and he distributed small cellophane packages of it to everyone he met, enthusiastically explaining its benefits.

He loved marijuana, too. He smoked it in vast quantities from his early twenties until the end of his life; wrote songs in praise of it; and persuaded his musician friends to smoke it when they played. He planned to call an unpublished sequel to his autobiography Gage, his pet name for marijuana, but once his manager found out about the title and the subject of the work, he suppressed the manuscript, trying to protect Louis's reputation. Sections of the work that survived the censorship show that he regarded it as an essential element in his life and beneficial to his health.

Louis had many nicknames throughout his life. They were part of the legacy of New Orleans, where, he said, "it was a pleasure to nickname someone and be named yourself. Fellers would greet each other, "Hello, Gate,' or 'Face' or whatever it was. Characters were called Nicodemus, Slippers, Sweet Child, Bo' Hog, so many more names. They'd be calling me Dipper, Gatemouth, Satchelmouth, all kinds of things, you know, Shadowmouth, any kind of name for a laugh....I had a million of 'em. Then I got Satchmo and I'm stuck with it. I like it." After journalists dubbed him "Satchmo," a corruption of "Satchelmouth," in the 1930s, it became his more or less official nickname, and it was the one he printed on his canary yellow stationery. Record companies called him Satchmo, too, because they recognized that it was good marketing. Who could resist a name like Satchmo? It was almost a trademark. In private, around friends, he referred to himself as Gate or Dipper, and he called them Daddy and Gate to express his affection and recognition. Most everyone who knew Louis called him Pops.

He made few enemies, if any. He loved to amuse, to startle, and to entertain, but as Duke Ellington pointed out, he "never hurt anyone" along the way. Most everyone liked him, or loved him, or forgave his addiction to crude clowning, or gradually succumbed to it because Louis Armstrong was a genius as well as a jester, and part of his genius was his exuberant temperament. He occasionally raged or lost his temper, usually with good reason, but never for long; there was nothing malicious about him. At times, he could be naive and reckless, but he always relied on his buoyant personality to rescue him from any jam he happened to find himself in, and his irrepressible optimism usually came to his rescue. He was the pursuit of happiness personified.

The grin was so endearing, and the growl so comforting, that it is easy to overlook Armstrong's essential subversiveness. Although he seemed to belong wholly to the mainstream, his principal allegiances were to the underground of American existence, from which he had emerged. His whole life can be read as a rebuke to bourgeois proprieties. Louis played, smoked, ate, made love, and lived as he damn well pleased. Although he wanted everyone to love him, at the same time, he didn't care much what people, especially those in authority, thought of him. He welcomed everyone into his orbit, especially outcasts--pimps, hustlers, hangers-on, even critics. He loved whores, having grown up among them. "Yeah, those were my people," he said in their defense, "and still are. Real people who never told me anything that wasn't right." He loved whores so much that he even married one. They met when he was her customer, and she tried to keep him in line with a small arsenal of knives and razors. Although he wasn't religious in any explicit sense, he believed he saw the spirit as plainly in sinners, thieves, and whores as he did in more conventional people.

In all, his was a distinctly American brand of optimism and striving. By reexamining his childhood and recasting it in the best possible light, he became the persona he employed to beguile the world, "Laughin' Louie." But there was more to his laughter than simple mirth. There was power and even an edge of anger to the laughter. It was a cosmic shout of defiance, a refusal to accept the status quo, and a determination to remake the world of his childhood and by extension, the world at large, as he believed it ought to be.

He thought he could accomplish this feat of legerdemain with his horn, his voice, and the jazz idiom, but in the end, it was Louis's animating spirit of joy, as much as his music, that was responsible for his transforming vision. No matter how much he suffered from the brutality of a caste system that consigned him to its lowest rank, he remained convinced his childhood was not the worst imaginable, but the best, overflowing with love, joy, and inspiration. "Every time I close my eyes blowing that trumpet of mine--I look right in the heart of good old New Orleans," he said. "It has given me something to live for."

To hear Louis tell it, or sing it, or blow it, no one else had ever enjoyed as privileged an existence as his New Orleans boyhood.

With this sound, he established more popular songs than any other musician. The sound had two components. There was, initially, a cornet--and later a trumpet--that was more expressive than a mere instrument: sweet, stinging, lilting, cajoling, teasing, ebullient. And then there was his voice, the unforgettable voice that behaved like a huge instrument: growling, laughing, demented, soothing, fierce. The combination of the voice that sounded like an instrument and the instrument that sounded like a voice created the universally recognized persona of Satchmo. He looked and felt like a glowing lump of coal, hot and alive and capable of igniting everything around him. For him, music was a heightened form of existence, and he sang and he played as if it could never be loud enough, or last long enough, or go deep enough, or reach high enough. He believed there could never be enough music in the world, and he did his damnedest to fill the silence with all the stomping, roaring, screeching, sighing polyphony he could muster.

He was not just America's greatest musical performer, he was also a character of epic proportions: married four times, with countless romantic involvements in and around his marriages ("Take your shoes off, Lucy, and let's get juicy," he growls in "Baby, It's Cold Outside"); a lifelong believer in marijuana for the head and laxatives for the bowels; an accomplished storyteller who tossed off letters and memoirs with the same abandon he tossed off riffs; and an enthusiastic correspondent who as a young man turned to his typewriter to record his experiences and his glorious hard times, the record of a black man trying to make his way in twentieth-century America.

It would be pleasant to memorialize Louis this way, as a happy innocent, his life an unbroken arc from the streets, dance halls, and brothels of New Orleans to the nightclubs, vaudeville theaters, and concert halls of Chicago, and New York, and then on to the sound stages of Hollywood and all the other venues and cradles of popular culture from Scandinavia to Africa, where he is revered. It would be heartwarming to envision him effortlessly breaking "color barriers" everywhere he went, with audiences screaming, "Satchmo, Satchmo," as he smiled and blew his horn and wiped his perspiring brow with his spotless white handkerchief and sang "Ain't Misbehavin'" and growled a few words of filthy comic asides to the band, and then smiled again and eagerly pumped the valves on his gleaming trumpet, and raised it to his scarred yet indestructible chops, and blew his horn some more.

It would be convenient if his life were that simple, but of course it wasn't, not at all.

It was, in all externals, a wretched childhood, yet Louis was obsessed with it and returned to it throughout his maturity as the wellspring of his identity, of his music, of jazz itself. From the time he purchased his first typewriter in 1922, Louis tapped out his reminiscences, observations, dirty stories, bawdy puns and limericks, and most anything else that popped into his superheated mind. Sometimes he wrote in his hotel rooms, and sometimes he wrote between sets, in the dressing room of whatever nightclub or theater he happened to be performing in. He spent almost as much time pounding the keys of his typewriter as he did pumping the valves of his trumpet. And he told the same tales with each instrument, which only made sense, because in his mind, he was jazz; to prove his point, he titled the first chapter of his autobiography, "Jazz and I Get Born Together." He was driven to review and renew the sources of his inspiration whenever he could. The further his ambitions, accomplishments, and fame took him from his childhood, the more avidly he sought to return to it--to re-create it onstage night after night, to reminisce compulsively about it with friends, and to recapture it in an outpouring of letters and memoirs both published and unpublished, that spare nothing and relish every amusing, odd, or gruesome detail of his boyhood. His cherished memories preserve a vanished, and, to many, unknown way of life--that of poor black people in New Orleans in the early decades of this century.[fcmps]

Louis wrote as he spoke, in torrents of phrases linked by ellipses, as if he were writing an endless gossip column, the gossip of his life. He preferred to write on his stationery, in green ink on yellow paper, and when that was not available, on hotel stationery, even on the back of an envelope containing a letter inside. He distributed his confessional letters across the world to his correspondents, and some of them later appeared in popular magazines such as True, Esquire, and Ebony, which were willing to run his raw tales of his youth and sexual adventures pretty much as he wrote them. Many others have found their way into libraries and archives, and countless others languish in private hands. Eventually, in his early fifties, he summoned the confidence to write his autobiography, published under the title Satchmo: My Life in New Orleans. He wrote it by himself, without the aid of a ghostwriter, secretary, or amanuensis, and the book became a summation of all the letters he had ever written and stories he had ever told about the good old, bad old days in New Orleans.

The outcome of all this ceaseless literary activity, which neatly complemented his musical outpouring, was a kind of self-analysis, for his writing always returned to the same cluster of themes: how I became who I am; how my experiences, especially as a boy, have left indelible marks on me; and, implicitly, how I learned to turn adversity into happiness most of the time, and music all the time. Though confessional, his writing was never intended to be private. Except when he was intent on saving his energy for a performance, Louis was exceptionally gregarious--too gregarious to confine his writing to a diary, and too much of an exhibitionist not to tell everybody, if only for sheer shock value. Writing was for him a transactional process, a conversation with another person, and his conversation always came back to the same point: how the grim circumstances into which he had been born and raised in fact constituted a charmed life, the ideal childhood for a jazz musician.

Louis's consciousness was unique and all-encompassing. He held nothing back. People who knew him well invariably use the same word to describe him: "natural." He always said exactly what was on his mind, usually a mixture of music, sex, food, laxatives, and childhood memories. Even at the age of seventy, he boasted of his sexual prowess, and throughout his life he happily described who he had just gone to bed with, whether it was his wife or a girlfriend, and what they had done, and how he felt about it--usually delighted. He also reveled in his bowel movements. These were occasions for rejoicing, and he was not shy about sharing his enthusiasm for them with the world. His stationery, for instance, showed him sitting on a toilet, pants down around his ankles, grinning, glimpsed as if through a keyhole, with the legend underneath: SATCHMO SAYS: LEAVE IT ALL BEHIND YA! He urged his friends to take the strong laxative he used, Swiss Kriss, a herbal remedy sold by the physical culturist Gayelord Hauser, and he distributed small cellophane packages of it to everyone he met, enthusiastically explaining its benefits.

He loved marijuana, too. He smoked it in vast quantities from his early twenties until the end of his life; wrote songs in praise of it; and persuaded his musician friends to smoke it when they played. He planned to call an unpublished sequel to his autobiography Gage, his pet name for marijuana, but once his manager found out about the title and the subject of the work, he suppressed the manuscript, trying to protect Louis's reputation. Sections of the work that survived the censorship show that he regarded it as an essential element in his life and beneficial to his health.

Louis had many nicknames throughout his life. They were part of the legacy of New Orleans, where, he said, "it was a pleasure to nickname someone and be named yourself. Fellers would greet each other, "Hello, Gate,' or 'Face' or whatever it was. Characters were called Nicodemus, Slippers, Sweet Child, Bo' Hog, so many more names. They'd be calling me Dipper, Gatemouth, Satchelmouth, all kinds of things, you know, Shadowmouth, any kind of name for a laugh....I had a million of 'em. Then I got Satchmo and I'm stuck with it. I like it." After journalists dubbed him "Satchmo," a corruption of "Satchelmouth," in the 1930s, it became his more or less official nickname, and it was the one he printed on his canary yellow stationery. Record companies called him Satchmo, too, because they recognized that it was good marketing. Who could resist a name like Satchmo? It was almost a trademark. In private, around friends, he referred to himself as Gate or Dipper, and he called them Daddy and Gate to express his affection and recognition. Most everyone who knew Louis called him Pops.

He made few enemies, if any. He loved to amuse, to startle, and to entertain, but as Duke Ellington pointed out, he "never hurt anyone" along the way. Most everyone liked him, or loved him, or forgave his addiction to crude clowning, or gradually succumbed to it because Louis Armstrong was a genius as well as a jester, and part of his genius was his exuberant temperament. He occasionally raged or lost his temper, usually with good reason, but never for long; there was nothing malicious about him. At times, he could be naive and reckless, but he always relied on his buoyant personality to rescue him from any jam he happened to find himself in, and his irrepressible optimism usually came to his rescue. He was the pursuit of happiness personified.

The grin was so endearing, and the growl so comforting, that it is easy to overlook Armstrong's essential subversiveness. Although he seemed to belong wholly to the mainstream, his principal allegiances were to the underground of American existence, from which he had emerged. His whole life can be read as a rebuke to bourgeois proprieties. Louis played, smoked, ate, made love, and lived as he damn well pleased. Although he wanted everyone to love him, at the same time, he didn't care much what people, especially those in authority, thought of him. He welcomed everyone into his orbit, especially outcasts--pimps, hustlers, hangers-on, even critics. He loved whores, having grown up among them. "Yeah, those were my people," he said in their defense, "and still are. Real people who never told me anything that wasn't right." He loved whores so much that he even married one. They met when he was her customer, and she tried to keep him in line with a small arsenal of knives and razors. Although he wasn't religious in any explicit sense, he believed he saw the spirit as plainly in sinners, thieves, and whores as he did in more conventional people.

In all, his was a distinctly American brand of optimism and striving. By reexamining his childhood and recasting it in the best possible light, he became the persona he employed to beguile the world, "Laughin' Louie." But there was more to his laughter than simple mirth. There was power and even an edge of anger to the laughter. It was a cosmic shout of defiance, a refusal to accept the status quo, and a determination to remake the world of his childhood and by extension, the world at large, as he believed it ought to be.

He thought he could accomplish this feat of legerdemain with his horn, his voice, and the jazz idiom, but in the end, it was Louis's animating spirit of joy, as much as his music, that was responsible for his transforming vision. No matter how much he suffered from the brutality of a caste system that consigned him to its lowest rank, he remained convinced his childhood was not the worst imaginable, but the best, overflowing with love, joy, and inspiration. "Every time I close my eyes blowing that trumpet of mine--I look right in the heart of good old New Orleans," he said. "It has given me something to live for."

To hear Louis tell it, or sing it, or blow it, no one else had ever enjoyed as privileged an existence as his New Orleans boyhood.

Descriere

Louis Armstrong was a man of epic proportions: a musical genius; a brilliant innovator; a showman who rose from poverty to international fame. This "full-bodied portrait of the artist and the man (is) far more interesting than his already colorful legend" ("USA Today"). of photos.