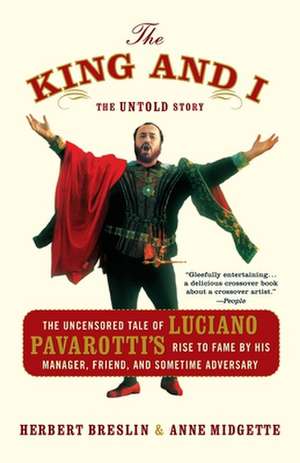

The King and I: The Uncensored Tale of Luciano Pavarotti's Rise to Fame by His Manager, Friend, and Sometime Adversary

Autor Herbert H. Breslin, Anne Midgetteen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 2005

The name “Luciano Pavarotti” is as central to the world of opera as high C’s and dueling sopranos. Pavarotti has had, quite inarguably, the most successful career in the history of the operatic profession, having gone from a once-reserved but brilliant tenor to a media-stupefying superstar. In The King and I, Herbert Breslin, Pavarotti’s publicist, manager, and friend for thirty-six years, reveals, in a fashion that is witty and bitingly frank, the truth about that white-hot career in all its delicious grandeur. Full of jaw-dropping anecdotes about the most famous divas and disputes of the past three decades, The King and I even features an afterword by the famed tenor himself. A one-of-a-kind read, The King and I is the ultimate backstage book about the greatest opera star ever.

Preț: 115.92 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 174

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.18€ • 23.22$ • 18.35£

22.18€ • 23.22$ • 18.35£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780767915083

ISBN-10: 0767915089

Pagini: 308

Dimensiuni: 140 x 217 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.44 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0767915089

Pagini: 308

Dimensiuni: 140 x 217 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.44 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

Recenzii

“A fascinating, often funny account of life with a full-blown diva.” —New York Post

“One of the most talked-about musical books of the [season] . . . offers considerable insight into the fiercely competitive world of opera.” —Tim Page, Washington Post

“Nasty and amusing . . . a wondrous orgy of Schadenfreude.” —Financial Times

“One of the most talked-about musical books of the [season] . . . offers considerable insight into the fiercely competitive world of opera.” —Tim Page, Washington Post

“Nasty and amusing . . . a wondrous orgy of Schadenfreude.” —Financial Times

Notă biografică

HERBERT BRESLIN has been a classical music publicist and manager for many of the greatest performers of our time for the past forty years.

ANNE MIDGETTE is a regular reviewer of classical music for the New York Times and has contributed to Opera News and many other music magazines.

ANNE MIDGETTE is a regular reviewer of classical music for the New York Times and has contributed to Opera News and many other music magazines.

Extras

chapter I

FROM CHRYSLER TO CARNEGIE HALL

Midlife Crisis: My Start in the Business

Here's how not to begin your brilliant professional career. In 1957, I was thirty-three years old. I was married, with a child on the way. And I was working as a speechwriter for the Chrysler Corporation. In Detroit, Michigan.

Detroit, Michigan. Who would even want to think about it? Misery.

People suppose that to succeed in the classical music business you should be very highly directed. You should have experience as a performer, so you know what it's like on the other side of the footlights. You should get your foot in the door early and work in a number of different areas so you get to know all sides of the performing arts. Ultimately, you'll gather the experience you need to set up your own company and manage top-level artists.

Well, that's all bullshit.

I came out of nowhere. I was smart. I was full of energy. And I had no idea what I wanted to do with my life. All I knew was that I loved music.

How much did I love music? I'd been obsessed with opera since I was eight years old. The beauty, the glamour, the excitement, and the tremendous voices pulled me into another world. I had a huge collection of records I listened to constantly. I had scrapbooks of the performances I'd seen and the artists I loved. Whatever else was going on around me, opera served as my own private support system and gave me tremendous sustenance. So much sustenance, in fact, that it became my life.

The problem I had when I was thirty-three was that it had nothing to do with my life. Especially not my life in Detroit. There's a little bit of music in Detroit, but nothing you would really want to seriously consider. I'm a New Yorker. I was starved for opera. I would get the New York Times and wistfully scan the cast lists at the Metropolitan Opera, which the Times used to print every Monday, for the two weeks ahead.

One week I saw that Renata Tebaldi was scheduled to sing Tosca, and I couldn't help myself. Tebaldi was one of the greatest sopranos singing. People portrayed her as a rival of Maria Callas: Tebaldi's pure vocal beauty against Callas's dramatic brilliance. Myself, I liked Callas fine, but I was a fierce fan of Renata Tebaldi. Intoxicating things happened when the woman opened her mouth. It was enough to make you fly to New York. I said to my wife, Carol, "We're going to see that Tosca," and I bought tickets.

Carol is a New Yorker, too, so she was game for a weekend in the city. She herself was prone to making dramatic pronouncements that she didn't want our first child to be born in Detroit. She was no happier living there than I was. She didn't completely share my passion for opera, but she was certainly happy to go, especially to see a performance as great as I promised her this one was going to be. By the time we walked into the old Met on Thirty-ninth Street, I was beside myself with excitement.

Imagine my feelings when I saw a notice in the lobby announcing that Madame Tebaldi was indisposed. Tosca would be sung by Antonietta Stella.

I went cold with disappointment. By today's standards, Antonietta Stella is nothing to sneeze at; but I hadn't flown in all the way from Detroit to hear Antonietta Stella sing Tosca. I couldn't believe my plans had been thwarted so cruelly, and I didn't want to accept it. I completely lost my temper. I said, "I do not want to hear this performance."

Opera houses, of course, don't refund a patron's ticket money if an artist cancels. Cancelations are practically part of opera routine. A singer's instrument--as any singer will be the first to tell you, and the second to tell you, and the last to tell you, so often do they reiterate it--is extremely fragile. A mild cold, a touch of allergies, a dry hotel room: any one of these things, and a thousand more, can keep them offstage. If opera houses refunded ticket money every time a big singer got sick, they'd all be even more broke than they already are.

I knew this, or some of this, at the time, but I didn't care. I let the box office know it. I said, "I do not want to hear anybody else. I do not want to have anything to do with this performance. I want my money back."

"We can't give you your money back," said the man at the box office window.

"I want my money back!" I said. By this point, I was raving like a banshee. Nobody knew what to do with me. My wife was standing by, looking a little bewildered at my behavior.

I made such a stink that they finally summoned Francis Robinson, who was the head of the box office in those days, to come out and deal with me. Francis was a lovely guy and extremely knowledgeable about all things operatic; he wrote a lot about the opera, and he ran the Met's public relations department. But I barely knew who he was that night, and he sure as hell didn't know who I was. I wasn't even in the music business. I was just some crank from Detroit making a ruckus in the lobby.

"How can I help you?" said Francis.

I said, "Mr. Robinson, I am not as insane as I may sound, but the fact of the matter is that I came in from Detroit to hear Madame Tebaldi, and I was looking forward to it so much. I know that she's sick. But I do not want to go and listen to this."

"Well," Francis said with a smile, "unfortunately there's not much we can do to bring Madame Tebaldi to tonight's performance. Listen. Go to the performance now, and we'll see about getting you a pair of tickets to Madame Tebaldi's next appearance."

He did, too. He was a lovely guy.

Later in my life, I always remembered that incident whenever fans got upset at a Luciano Pavarotti cancelation. You come all that way for something you're really excited to see, and then your hopes are dashed. It's like having the rug pulled out from under you. I knew exactly how they felt.

Not that I ever gave any of them a free pair of tickets as compensation. I'd be in the poorhouse.

Little did I know that night at the Met that within a few years I would be Renata Tebaldi's press agent. I might have felt better.

As I said, I was hooked on opera from childhood--from the day my father took me to see Carmen at the New York Hippodrome, on Sixth Avenue at Forty-fourth Street. I don't know exactly why he took me; it wasn't as if we went to performances all the time. We were not people of great means. But he did love music. And Carmen, with its rousing tunes and gripping drama, was a great first opera. My father couldn't have suspected what he had started.

By the time I was a teenager, every spare penny I had was going for opera. From our home in the Bronx, I'd take the subway down to Manhattan and wait on the line for standing-room tickets. There was a real camaraderie on that line in those days. My friend Myron Egan, who was killed in the war, and I went together and saw everything and everybody that we could. After the show, we'd wait for the artists to come out and get their autographs. And what artists. In those days, it was the ladies who ruled opera: we went to hear the sopranos. Grace Moore, the glamorous American soprano, killed in a plane crash at age forty-eight: I heard her debut as Tosca. Zinka Milanov, the Yugoslavian who looked like a potato and sang like a goddess: somewhere I still have a picture that she autographed for me sixty years ago.

I fantasized about being a singer myself. But since I didn't have a lot of financial resources, I also had to pay close attention to what was practical. To help pay for all of my opera activity, I occasionally took a job in opera itself--as a supernumerary in the big operas, like Aida, that call for a lot of warm bodies onstage. In those days, you got paid something like two dollars for being a super. I got a little extra, because I always tried to take home a piece of my costume as a souvenir. I soon added a wig, a helmet, and a number of other items to my collection of opera memorabilia. I saw myself as a self-supporter, which was something that turned out to be very useful to me.

When I look back, all the dates in my life are marked by the music I heard. Well, nearly all. When I first went into the army in 1943, I was stationed in Nebraska, and there was no music there at all. My job was to guard the German and Italian POWs as they worked in the fields. My great contribution to the war effort was overseeing the harvest of the sugar beet crop in western Nebraska. The Italians were very lazy; you had to push them to get the work done. Come to think of it, this first exposure to the Italian mentality may have stood me in good stead in my professional life.

Later in the war, I did get music. In 1944, I was transferred to Camp Crowder, Missouri, and I went to Joplin, Missouri, to hear a recital by a wonderful soprano named Miliza Korjus, a lovely looking woman, if a little zaftig, who had starred in the film The Great Waltz, about Johann Strauss. It should have been called The Great Schmaltz, but she sang well. She could venture into a stratospheric range to which few singers could aspire.

In 1945, I went to Europe as a cryptographer with the army signal corps, following right behind Eisenhower. Army HQ was in Reims, France, and I took a day trip to Paris and went to the Opera-Comique, where I heard Puccini's Madama Butterfly with a soprano named Jeanne Segala. Eisenhower moved on to Frankfurt, where all the theaters were bombed out; they were putting on opera performances in the basement of the Borsensaal, the stock exchange, and I attended a Tosca and Mozart's Nozze di Figaro down there. On my furlough, I went to Rome, where at the Teatro Reale I heard Maria Caniglia, the soaring Italian soprano, in Verdi's La Traviata. I adored Europe. I even found a voice teacher in Reims named Madame Patou, who gave me lessons once or twice a week in exchange for money, as well as coffee and sugar and other things I brought her that were very hard to get in those days. I would say I was a tenor of some kind. I was a rather immature student; I had never studied music, and I couldn't read music. She tried to teach me solfège, the art of sight-reading with musical syllables, and I didn't know what the hell she was talking about. But I still remember some of the songs she taught me.

In 1948, I heard Giuseppe di Stefano, the great Italian tenor, and the mezzo-soprano Risë Stevens in Ambroise Thomas's sentimental opera Mignon. That was back in New York. I didn't necessarily want to be back in New York, but when the war ended, I was twenty-one years old and I didn't know what to do with my life. I was so full of drive and energy that I knew I wanted to do something, but I had no marketable skills. I wasn't an artist, I wasn't a writer, and I didn't have much experience doing much of anything. I was just a person, with no way to express myself. I tried to tell my parents that all I wanted to do was stay in Europe, but they wouldn't hear of it. What would I do in Europe? they wanted to know. I didn't really have an answer to that, other than "Sweep the streets," so I got on a boat and sailed back to the States, with no idea what was going to be happening to me. I was completely lost. I stood on the upper deck of the ship--the Ernie Pyle--as it was pulling out of Le Havre, and I looked out over the port, and at France behind it, and I said to myself, "I'm coming back." It was my first concrete ambition.

And I achieved it. In 1949, I heard the German soprano Maria Reining, a fantastic singer, as the Marschallin in Richard Strauss's Der Rosenkavalier. I was back in Paris. In New York, I had gotten my college degree in business administration from the City University of New York and had taken a job in an import-export company. From my princely salary of $35 a week, I saved $10 a week, religiously, and at the end of two years I had $1,000 and was ready to go back to Europe. I still didn't have any idea what I was going to do when I got there, but I learned that the GI Bill would pay you $75 a month if you went to school, so I decided to enroll at the Sorbonne and take a course in la civilisation francaise. I didn't speak any French, but I didn't let that worry me. I figured I would pick it up. So I sailed back to Europe in June of 1949 on the George Washington, an old troopship that had been reconverted for passenger use. It wasn't that easy to find passage in those days--a lot of people wanted to go, and the possibilities were limited--but I did. I think I would have swum if I'd had to. When I got on that boat, I was in a state of excitement and anticipation that words can hardly bring across. I was beside myself. Until that point in my life, I had never had exactly what I wanted, but I knew that this, now, was the real me, going where I wanted, and I had made it happen.

My stay in Paris was everything I'd hoped for. I found lodgings at the Maison Francaise at the Cité Universitaire, where all the students lived; I hung out at Le Select, the famous cafe in Montparnasse; I went to some of the political rallies that were going on in France at that very turbulent time, led by people like Maurice Thorez, the head of the French Communist Party. I felt I was in the thick of things, which was a place I was very anxious to be in those days, even though I never was actually in the thick of anything. But once my time was up, I had to go home again--and think of another way to get myself back.

FROM CHRYSLER TO CARNEGIE HALL

Midlife Crisis: My Start in the Business

Here's how not to begin your brilliant professional career. In 1957, I was thirty-three years old. I was married, with a child on the way. And I was working as a speechwriter for the Chrysler Corporation. In Detroit, Michigan.

Detroit, Michigan. Who would even want to think about it? Misery.

People suppose that to succeed in the classical music business you should be very highly directed. You should have experience as a performer, so you know what it's like on the other side of the footlights. You should get your foot in the door early and work in a number of different areas so you get to know all sides of the performing arts. Ultimately, you'll gather the experience you need to set up your own company and manage top-level artists.

Well, that's all bullshit.

I came out of nowhere. I was smart. I was full of energy. And I had no idea what I wanted to do with my life. All I knew was that I loved music.

How much did I love music? I'd been obsessed with opera since I was eight years old. The beauty, the glamour, the excitement, and the tremendous voices pulled me into another world. I had a huge collection of records I listened to constantly. I had scrapbooks of the performances I'd seen and the artists I loved. Whatever else was going on around me, opera served as my own private support system and gave me tremendous sustenance. So much sustenance, in fact, that it became my life.

The problem I had when I was thirty-three was that it had nothing to do with my life. Especially not my life in Detroit. There's a little bit of music in Detroit, but nothing you would really want to seriously consider. I'm a New Yorker. I was starved for opera. I would get the New York Times and wistfully scan the cast lists at the Metropolitan Opera, which the Times used to print every Monday, for the two weeks ahead.

One week I saw that Renata Tebaldi was scheduled to sing Tosca, and I couldn't help myself. Tebaldi was one of the greatest sopranos singing. People portrayed her as a rival of Maria Callas: Tebaldi's pure vocal beauty against Callas's dramatic brilliance. Myself, I liked Callas fine, but I was a fierce fan of Renata Tebaldi. Intoxicating things happened when the woman opened her mouth. It was enough to make you fly to New York. I said to my wife, Carol, "We're going to see that Tosca," and I bought tickets.

Carol is a New Yorker, too, so she was game for a weekend in the city. She herself was prone to making dramatic pronouncements that she didn't want our first child to be born in Detroit. She was no happier living there than I was. She didn't completely share my passion for opera, but she was certainly happy to go, especially to see a performance as great as I promised her this one was going to be. By the time we walked into the old Met on Thirty-ninth Street, I was beside myself with excitement.

Imagine my feelings when I saw a notice in the lobby announcing that Madame Tebaldi was indisposed. Tosca would be sung by Antonietta Stella.

I went cold with disappointment. By today's standards, Antonietta Stella is nothing to sneeze at; but I hadn't flown in all the way from Detroit to hear Antonietta Stella sing Tosca. I couldn't believe my plans had been thwarted so cruelly, and I didn't want to accept it. I completely lost my temper. I said, "I do not want to hear this performance."

Opera houses, of course, don't refund a patron's ticket money if an artist cancels. Cancelations are practically part of opera routine. A singer's instrument--as any singer will be the first to tell you, and the second to tell you, and the last to tell you, so often do they reiterate it--is extremely fragile. A mild cold, a touch of allergies, a dry hotel room: any one of these things, and a thousand more, can keep them offstage. If opera houses refunded ticket money every time a big singer got sick, they'd all be even more broke than they already are.

I knew this, or some of this, at the time, but I didn't care. I let the box office know it. I said, "I do not want to hear anybody else. I do not want to have anything to do with this performance. I want my money back."

"We can't give you your money back," said the man at the box office window.

"I want my money back!" I said. By this point, I was raving like a banshee. Nobody knew what to do with me. My wife was standing by, looking a little bewildered at my behavior.

I made such a stink that they finally summoned Francis Robinson, who was the head of the box office in those days, to come out and deal with me. Francis was a lovely guy and extremely knowledgeable about all things operatic; he wrote a lot about the opera, and he ran the Met's public relations department. But I barely knew who he was that night, and he sure as hell didn't know who I was. I wasn't even in the music business. I was just some crank from Detroit making a ruckus in the lobby.

"How can I help you?" said Francis.

I said, "Mr. Robinson, I am not as insane as I may sound, but the fact of the matter is that I came in from Detroit to hear Madame Tebaldi, and I was looking forward to it so much. I know that she's sick. But I do not want to go and listen to this."

"Well," Francis said with a smile, "unfortunately there's not much we can do to bring Madame Tebaldi to tonight's performance. Listen. Go to the performance now, and we'll see about getting you a pair of tickets to Madame Tebaldi's next appearance."

He did, too. He was a lovely guy.

Later in my life, I always remembered that incident whenever fans got upset at a Luciano Pavarotti cancelation. You come all that way for something you're really excited to see, and then your hopes are dashed. It's like having the rug pulled out from under you. I knew exactly how they felt.

Not that I ever gave any of them a free pair of tickets as compensation. I'd be in the poorhouse.

Little did I know that night at the Met that within a few years I would be Renata Tebaldi's press agent. I might have felt better.

As I said, I was hooked on opera from childhood--from the day my father took me to see Carmen at the New York Hippodrome, on Sixth Avenue at Forty-fourth Street. I don't know exactly why he took me; it wasn't as if we went to performances all the time. We were not people of great means. But he did love music. And Carmen, with its rousing tunes and gripping drama, was a great first opera. My father couldn't have suspected what he had started.

By the time I was a teenager, every spare penny I had was going for opera. From our home in the Bronx, I'd take the subway down to Manhattan and wait on the line for standing-room tickets. There was a real camaraderie on that line in those days. My friend Myron Egan, who was killed in the war, and I went together and saw everything and everybody that we could. After the show, we'd wait for the artists to come out and get their autographs. And what artists. In those days, it was the ladies who ruled opera: we went to hear the sopranos. Grace Moore, the glamorous American soprano, killed in a plane crash at age forty-eight: I heard her debut as Tosca. Zinka Milanov, the Yugoslavian who looked like a potato and sang like a goddess: somewhere I still have a picture that she autographed for me sixty years ago.

I fantasized about being a singer myself. But since I didn't have a lot of financial resources, I also had to pay close attention to what was practical. To help pay for all of my opera activity, I occasionally took a job in opera itself--as a supernumerary in the big operas, like Aida, that call for a lot of warm bodies onstage. In those days, you got paid something like two dollars for being a super. I got a little extra, because I always tried to take home a piece of my costume as a souvenir. I soon added a wig, a helmet, and a number of other items to my collection of opera memorabilia. I saw myself as a self-supporter, which was something that turned out to be very useful to me.

When I look back, all the dates in my life are marked by the music I heard. Well, nearly all. When I first went into the army in 1943, I was stationed in Nebraska, and there was no music there at all. My job was to guard the German and Italian POWs as they worked in the fields. My great contribution to the war effort was overseeing the harvest of the sugar beet crop in western Nebraska. The Italians were very lazy; you had to push them to get the work done. Come to think of it, this first exposure to the Italian mentality may have stood me in good stead in my professional life.

Later in the war, I did get music. In 1944, I was transferred to Camp Crowder, Missouri, and I went to Joplin, Missouri, to hear a recital by a wonderful soprano named Miliza Korjus, a lovely looking woman, if a little zaftig, who had starred in the film The Great Waltz, about Johann Strauss. It should have been called The Great Schmaltz, but she sang well. She could venture into a stratospheric range to which few singers could aspire.

In 1945, I went to Europe as a cryptographer with the army signal corps, following right behind Eisenhower. Army HQ was in Reims, France, and I took a day trip to Paris and went to the Opera-Comique, where I heard Puccini's Madama Butterfly with a soprano named Jeanne Segala. Eisenhower moved on to Frankfurt, where all the theaters were bombed out; they were putting on opera performances in the basement of the Borsensaal, the stock exchange, and I attended a Tosca and Mozart's Nozze di Figaro down there. On my furlough, I went to Rome, where at the Teatro Reale I heard Maria Caniglia, the soaring Italian soprano, in Verdi's La Traviata. I adored Europe. I even found a voice teacher in Reims named Madame Patou, who gave me lessons once or twice a week in exchange for money, as well as coffee and sugar and other things I brought her that were very hard to get in those days. I would say I was a tenor of some kind. I was a rather immature student; I had never studied music, and I couldn't read music. She tried to teach me solfège, the art of sight-reading with musical syllables, and I didn't know what the hell she was talking about. But I still remember some of the songs she taught me.

In 1948, I heard Giuseppe di Stefano, the great Italian tenor, and the mezzo-soprano Risë Stevens in Ambroise Thomas's sentimental opera Mignon. That was back in New York. I didn't necessarily want to be back in New York, but when the war ended, I was twenty-one years old and I didn't know what to do with my life. I was so full of drive and energy that I knew I wanted to do something, but I had no marketable skills. I wasn't an artist, I wasn't a writer, and I didn't have much experience doing much of anything. I was just a person, with no way to express myself. I tried to tell my parents that all I wanted to do was stay in Europe, but they wouldn't hear of it. What would I do in Europe? they wanted to know. I didn't really have an answer to that, other than "Sweep the streets," so I got on a boat and sailed back to the States, with no idea what was going to be happening to me. I was completely lost. I stood on the upper deck of the ship--the Ernie Pyle--as it was pulling out of Le Havre, and I looked out over the port, and at France behind it, and I said to myself, "I'm coming back." It was my first concrete ambition.

And I achieved it. In 1949, I heard the German soprano Maria Reining, a fantastic singer, as the Marschallin in Richard Strauss's Der Rosenkavalier. I was back in Paris. In New York, I had gotten my college degree in business administration from the City University of New York and had taken a job in an import-export company. From my princely salary of $35 a week, I saved $10 a week, religiously, and at the end of two years I had $1,000 and was ready to go back to Europe. I still didn't have any idea what I was going to do when I got there, but I learned that the GI Bill would pay you $75 a month if you went to school, so I decided to enroll at the Sorbonne and take a course in la civilisation francaise. I didn't speak any French, but I didn't let that worry me. I figured I would pick it up. So I sailed back to Europe in June of 1949 on the George Washington, an old troopship that had been reconverted for passenger use. It wasn't that easy to find passage in those days--a lot of people wanted to go, and the possibilities were limited--but I did. I think I would have swum if I'd had to. When I got on that boat, I was in a state of excitement and anticipation that words can hardly bring across. I was beside myself. Until that point in my life, I had never had exactly what I wanted, but I knew that this, now, was the real me, going where I wanted, and I had made it happen.

My stay in Paris was everything I'd hoped for. I found lodgings at the Maison Francaise at the Cité Universitaire, where all the students lived; I hung out at Le Select, the famous cafe in Montparnasse; I went to some of the political rallies that were going on in France at that very turbulent time, led by people like Maurice Thorez, the head of the French Communist Party. I felt I was in the thick of things, which was a place I was very anxious to be in those days, even though I never was actually in the thick of anything. But once my time was up, I had to go home again--and think of another way to get myself back.

Descriere

"The King and I" is the story of the 36-year business relationship between Luciano Pavarotti and his manager Breslin, during which Breslin guided what he calls, justifiably, "the greatest career in classical music."