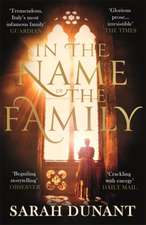

Mapping The Edge

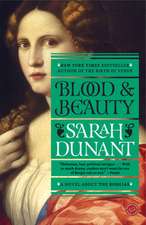

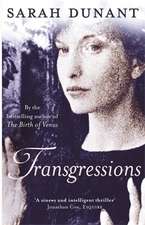

Autor Sarah Dunanten Limba Engleză Paperback – 7 iul 2005

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 49.46 lei 3-5 săpt. | +25.98 lei 6-12 zile |

| Little Brown Book Group – 7 iul 2005 | 49.46 lei 3-5 săpt. | +25.98 lei 6-12 zile |

| Random House Trade – 31 ian 2002 | 106.86 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 49.46 lei

Preț vechi: 64.11 lei

-23% Nou

Puncte Express: 74

Preț estimativ în valută:

9.46€ • 10.12$ • 7.89£

9.46€ • 10.12$ • 7.89£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 27 martie-10 aprilie

Livrare express 12-18 martie pentru 35.97 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781844081769

ISBN-10: 1844081761

Pagini: 352

Dimensiuni: 128 x 196 x 26 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Editura: Little Brown Book Group

Locul publicării:United Kingdom

ISBN-10: 1844081761

Pagini: 352

Dimensiuni: 128 x 196 x 26 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Editura: Little Brown Book Group

Locul publicării:United Kingdom

Notă biografică

Sarah Dunant has written six suspense novels, three of which have been shortlisted for Britain’s prestigious Golden Dagger award. Her novel Fatlands won the Silver Dagger. As a journalist and critic, she has worked extensively in print, radio, and television, where for many years she hosted her own show on the BBC. She lives in London with her family.

Extras

Departure lounge, South Terminal, Gatwick Airport. A shopper's paradise: two floors of superior retail space connected by gliding glass lifts and peopled by an endless stream of travelers, processed to have time on their hands and a permanent discount at the wave of a boarding card. If you are smart you come here with an empty case and do your packing as you walk: cosmetics, toiletries, clothes, shoes, books, perfumes, booze, cameras, films. For many the holiday starts here. You can see it in their faces. People shop differently, none of that suburban mall madness. Instead they stroll and browse, couples with their arms around each other, the beach saunter already in their stride, children dancing behind their parents in the hermetic safety of a controlled environment. When did you last read a horror story about a child abducted in a departure lounge?

Second floor, a cappuccino bar with tables out on the concourse, next to the Body Shop and Accessorize. A woman is sitting alone at a table, a small holdall by her side, her boarding card lying near to a plastic cup in front of her. She has no carrier bags, no duty free. She is not interested in shopping. Instead she is watching others and thinking about how it was twenty years before when she came to this airport as a teenager, on her first solo flight to Europe. None of this existed then. Before the invention of niche marketing, air travel had been a serious, more reverent affair. People wore their best clothes for flying then, and duty free meant two hundred Rothmans and a bottle of Elizabeth Arden perfume. It seems as far away as black-and-white photography. At that time her flight had been delayed for three hours. Too young for cheap booze and too poor for perfume, she had sat in a row of red bucket chairs nailed to the ground and read her guidebooks, mapping a city she had only ever visited in her mind, trying to quieten the tumbling adrenaline inside her. The rest of her life had been waiting on the other side of Gate 3 and she had been aching to walk into it.

It is not the same now. Now, though there is adrenaline it has no playfulness within it. Instead it burns the insides of her stomach, feeding off apprehension and caffeine. There are moments when she wishes she hadn't come. Or that she had brought Lily with her. Lily would have loved the circus of it all; her chatter would have filled up the silence, her curiosity would have nudged the cynicism toward wonder. But this is not Lily's journey. Her absence is part of the point.

She pushes the coffee cup away from her and slips the boarding card back into her pocket. When she last looked at the monitor the Pisa flight was still waiting to board. Now it is flashing last call. Gate 37. She gets up and walks toward the glass lift.

Twenty years ago as she made this last walk there had been a Beatles track playing in her head. "She's Leaving Home." It was dated by then, already ironic. It had made her smile. Maybe that was her problem. She was no longer comforted by irony.

Amsterdam

Friday p.m.

On Friday evenings I like to take drugs. I suppose you could call it a habit, though hardly a serious one. I see it, rather, as a way to relax; the end of work, the need to let go, welcome the weekend, that kind of thing. Sometimes it's dope, sometimes it's alcohol. Like most things in my life it has a routine. I come in, turn on the radio, roll a spliff, sit at the kitchen table, and wait for the world to uncurl. I like the way life becomes when I'm stoned: more malleable, softer at the edges. It feels familiar to me. Reassuring. I've been doing it a long time. I started smoking when I was in my teens. I got my first stash from the boyfriend of a friend: an early example of adolescent free enterprise. The first time I smoked there were other people around, but it didn't take me long to discover solitude. I used to sit upstairs and blow the smoke out of my bedroom window. If my father knew (and it seems impossible to me now that he didn't) he was smart enough not to call me on it. I was never into rebellion, only into solitude. And being stoned. And so it has continued throughout my life. Though you probably wouldn't know it from meeting me. I don't look the type, you see. It has always been one of my greatest talents, that in the nine-to-five game I come over as the professional to my fingertips, brain like my clothes: sharp lines and no frills. Straight, in other words. One of life's good girls. The kind you can depend on. But everyone has to slip off their shoulder pads sometimes.

Second floor, a cappuccino bar with tables out on the concourse, next to the Body Shop and Accessorize. A woman is sitting alone at a table, a small holdall by her side, her boarding card lying near to a plastic cup in front of her. She has no carrier bags, no duty free. She is not interested in shopping. Instead she is watching others and thinking about how it was twenty years before when she came to this airport as a teenager, on her first solo flight to Europe. None of this existed then. Before the invention of niche marketing, air travel had been a serious, more reverent affair. People wore their best clothes for flying then, and duty free meant two hundred Rothmans and a bottle of Elizabeth Arden perfume. It seems as far away as black-and-white photography. At that time her flight had been delayed for three hours. Too young for cheap booze and too poor for perfume, she had sat in a row of red bucket chairs nailed to the ground and read her guidebooks, mapping a city she had only ever visited in her mind, trying to quieten the tumbling adrenaline inside her. The rest of her life had been waiting on the other side of Gate 3 and she had been aching to walk into it.

It is not the same now. Now, though there is adrenaline it has no playfulness within it. Instead it burns the insides of her stomach, feeding off apprehension and caffeine. There are moments when she wishes she hadn't come. Or that she had brought Lily with her. Lily would have loved the circus of it all; her chatter would have filled up the silence, her curiosity would have nudged the cynicism toward wonder. But this is not Lily's journey. Her absence is part of the point.

She pushes the coffee cup away from her and slips the boarding card back into her pocket. When she last looked at the monitor the Pisa flight was still waiting to board. Now it is flashing last call. Gate 37. She gets up and walks toward the glass lift.

Twenty years ago as she made this last walk there had been a Beatles track playing in her head. "She's Leaving Home." It was dated by then, already ironic. It had made her smile. Maybe that was her problem. She was no longer comforted by irony.

Amsterdam

Friday p.m.

On Friday evenings I like to take drugs. I suppose you could call it a habit, though hardly a serious one. I see it, rather, as a way to relax; the end of work, the need to let go, welcome the weekend, that kind of thing. Sometimes it's dope, sometimes it's alcohol. Like most things in my life it has a routine. I come in, turn on the radio, roll a spliff, sit at the kitchen table, and wait for the world to uncurl. I like the way life becomes when I'm stoned: more malleable, softer at the edges. It feels familiar to me. Reassuring. I've been doing it a long time. I started smoking when I was in my teens. I got my first stash from the boyfriend of a friend: an early example of adolescent free enterprise. The first time I smoked there were other people around, but it didn't take me long to discover solitude. I used to sit upstairs and blow the smoke out of my bedroom window. If my father knew (and it seems impossible to me now that he didn't) he was smart enough not to call me on it. I was never into rebellion, only into solitude. And being stoned. And so it has continued throughout my life. Though you probably wouldn't know it from meeting me. I don't look the type, you see. It has always been one of my greatest talents, that in the nine-to-five game I come over as the professional to my fingertips, brain like my clothes: sharp lines and no frills. Straight, in other words. One of life's good girls. The kind you can depend on. But everyone has to slip off their shoulder pads sometimes.

Recenzii

“Very smart . . . a riveting thriller.” —Baltimore Sun

“What if we cannot know even those we love best? In Mapping the Edge, Sarah Dunant writes with wonderful intelligence about the dark intricacies of motherhood, friendship, love, and obsession. A brilliantly plotted, ruthlessly intelligent, and highly readable novel.”

—Margot Livesey, author of Eva Moves the Furniture

“[Dunant] plots with remarkable intricacy [and] is a master at creating anxiety and mystery.” —The Washington Post

“Thoroughly satisfying . . . departs from the usual thriller formula . . . but it contains its own full array of surprises. . . . Dunant’s feel for the geography of bed and willing flesh is a pleasure. . . . In moments . . . that delve into the subtleties and varieties of love and desire, Dunant emerges as a shrewd observer.”

—The New York Times Book Review

“What if we cannot know even those we love best? In Mapping the Edge, Sarah Dunant writes with wonderful intelligence about the dark intricacies of motherhood, friendship, love, and obsession. A brilliantly plotted, ruthlessly intelligent, and highly readable novel.”

—Margot Livesey, author of Eva Moves the Furniture

“[Dunant] plots with remarkable intricacy [and] is a master at creating anxiety and mystery.” —The Washington Post

“Thoroughly satisfying . . . departs from the usual thriller formula . . . but it contains its own full array of surprises. . . . Dunant’s feel for the geography of bed and willing flesh is a pleasure. . . . In moments . . . that delve into the subtleties and varieties of love and desire, Dunant emerges as a shrewd observer.”

—The New York Times Book Review