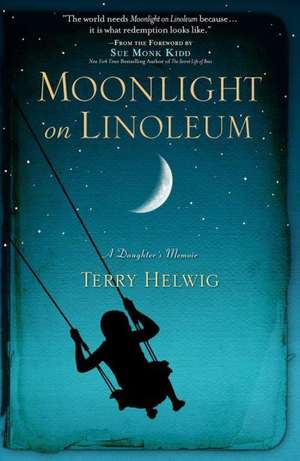

Moonlight on Linoleum: A Daughter's Memoir

Autor Terry Helwig Cuvânt înainte de Sue Monk Kidden Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2012

This simple truth became Terry Helwig’s lifeline as she was forced to grow up too soon.

Terry grew up the oldest of six girls in the big-sky country of the American Southwest, where she attended twelve schools in eleven years. Helwig’s stepfather Davy, a good-hearted and loving man, proudly purchased a mobile home to enable his family to move more easily from one oil town to another, where Davy eked out a living in the oil fields.

Terry’s mother, Carola Jean, a wild rose whose love often pierced those who tried to claim her, had little interest in the confines of home and motherhood. In Davy’s absence, she sought companionship in local watering holes—a pastime she dubbed “visiting Timbuktu.” She repeatedly left Terry in charge of the household and her five younger sisters.

Despite Carola Jean’s genuine attempts to “better herself,” her life spiraled ever downward as Terry struggled to keep the family whole. In the midst of transience and upheaval, Terry and her sisters forged an uncommon bond of sisterhood that withstood the erosion of Davy and Carola Jean’s marriage. But ultimately, to keep her own dreams alive, Terry had to decide when to hold on to what she loved and when to let go.

Unflinching in its portrayal, yet told with humor and compassion, Terry Helwig’s luminous memoir, Moonlight on Linoleum, explores a family’s inner and outer landscapes of hope, despair, and redemption. It will make you laugh, cry, and hunger for more.

Preț: 112.93 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 169

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.61€ • 22.39$ • 18.04£

21.61€ • 22.39$ • 18.04£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-15 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781451628678

ISBN-10: 1451628676

Pagini: 304

Ilustrații: 8 pg b-w insert

Dimensiuni: 140 x 214 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Howard Books

Colecția Howard Books

ISBN-10: 1451628676

Pagini: 304

Ilustrații: 8 pg b-w insert

Dimensiuni: 140 x 214 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Howard Books

Colecția Howard Books

Notă biografică

Teresa Helwig graduated with an MA in counseling psychology and for many years was a human development specialist, writing, lecturing, and leading workshops on personal growth and spiritual development. She is the founder and curator of The Thread Project and she and her husband currently divide their time between South Carolina and Florida.

Extras

Emerson, Iowa

1950

“I left your Dad,” Mama told me more than once, “because I didn’t want to kill him.”

She wasn’t kidding.

Mama said she stood at the kitchen counter, her hand touching the smooth wooden handle of a butcher knife. In an argument that grew more heated, Mama felt her fist close around the handle. For a brief moment, she deliberated between slashing our father with the knife or releasing it harmlessly back onto the counter and walking away.

My sister Vicki was ten months old; I was two. Mama was seventeen.

By all accounts, Mom and Dad loved one another, even though Mama lied about her age. Mama told my dad that she had celebrated her eighteenth birthday; Dad, twenty-two, believed her. But the State of Iowa insisted on seeing Mama’s record of birth before granting them a marriage license. Only then did Mama confess her lie to my dad. He broke down and cried. Mama was fourteen, not eighteen. Still, despite the deceit and age difference, on Wednesday, May 26, 1948, Carola Jean Simmonds and Donald Lee Skinner said “I do.” Mama’s mother signed her consent.

Mama definitely looked older than fourteen. She had thick black hair that fell around her face, accenting the widow’s peak she inherited from her mother. Her hazel eyes reflected not a shy, timid girl, but held a womanly gaze that belied her years. Physically, she was curved and bosomed. But she was not pregnant. According to my birth certificate, I came along a full eleven months after they married, proving their union sprang from something other than necessity.

Part of Mama’s motivation may have sprung from her eagerness to leave home. Her older brother, my Uncle Gaylen, witnessed the difficult relationship Mama had with their mother.

“This is hard to tell,” he said. “When your mom was just a baby, I remember walking alongside her baby carriage with our mom. I must have been about eight. Carola was crying and crying and Mom got so mad. She stopped the carriage, walked to a nearby tree, and yanked off a switch. She returned to the carriage and whipped your mom for crying. I couldn’t believe she was whipping a baby.”

Uncle Gaylen fumbled for words, attributing his mom’s state of mind to my grandfather Gashum’s infidelity. “I think Mom took out all her frustrations on Carola,” he said.

I wish I could scrub that stain from our family’s history. I wish I could reach back in time, snatch the switch from Grandma’s raised fist, and snap it across my knee. It might have made a difference. Mama’s life might have taken a different turn.

She might not have been so desperate for tenderness.

By the time Mama turned fourteen, she had fallen for my dad. Instead of protesting when Mama asked to marry him, Grandma extolled my father’s family, told Mama she was lucky to have him, and readily signed permission for Mama to marry. With the words “I do” uttered in the sleepy town of Glenwood, Iowa, Mama became a fourteen-year-old tenant farmer’s wife.

Around that time, Mama wrote a couple of jingles and sold them to Burma Shave as part of their road-side advertising campaign. Mama liked to drive by a particular set of red and white signs posted successively along the highway near Glenwood. The words on the signs, which built toward a punchline farther down the road, were Mama’s words, right there in plain daylight, for the whole world to see.

His cheek

Was rough

His chick vamoosed

And now she won’t

Come home to roost

Burma Shave

It’s impossible to know which jingles Mama wrote, but, all her life, she loved the word vamoose.

During the first year of their marriage, my parents moved into a house without running water, off County Road L-45 not far from the Waubonsie Church and Cemetery outside Glenwood. Dad, a farmer, loved the land and spent long hours plowing, planting, and tending the livestock. His mother, my Grandma Skinner, lived four miles down the gravel road. Grandma Skinner had raised six children while slopping the pigs, sewing, planting a garden, canning, baking, and putting hearty meals on the table three times a day. I think Dad assumed all women inherited Grandma’s Hestian gene.

But not his child-bride, Carola Jean. She could write a jingle, but she knew nothing about cooking, gardening, cleaning, or running a household—not even how to iron.

“Your mom couldn’t keep up with the house or the laundry,” Aunt Dixie, my dad’s sister, said years later. “If she ran out of diapers, she’d pin curtains or dishtowels on you, anything she could get her hands on.”

I doubt Mama knew what to do with a screaming colicky baby either, one who smelled of sour milk and required little sleep. In a house without running water, I must have contributed to a legion of laundry and fatigue. The doctor finally determined I suffered from a milk allergy and switched me to soy milk, which cured my colic, but not my aversion to sleep.

“In desperation,” Mama recounted many times, “I scooted your crib close enough to the bed to reach my hand through the slats to hold your hand. Finally you’d settle down, but—” Mama would draw in a long breath here—“if I let go, you’d wake up and start crying all over again. You always wanted to be near me. Sometimes I cried, too.”

Without fail, the next part of her story included a comparison between me and my sister Vicki, born fourteen months later.

“Now, Vicki was just the opposite,” Mama marveled. “I’d have to keep thumping her on her heel just to keep her awake long enough to eat.”

Mama’s retelling of that story during our growing-up years made me feel like thumping Vicki, too, and it had nothing to do with staying awake. I pictured Vicki sleeping peacefully and wished I had been an easier child. More than once I wanted to shout, I can’t help what I did as a baby! But I held my tongue; I was good at that.

By the time Vicki joined our household, we lived in a former rural schoolhouse near Emerson, Iowa. It was here that Mama broke.

She was sixteen.

No matter how you do the math, the equation always comes out the same; Mama was little more than a child herself. The rigors of marriage, farm life, and two girls under the age of two finally came crashing down on her.

Mama had adopted a kitten, much to my delight and my dad’s dismay. Dad did not want animals in the house. But Mama stood her ground; the kitten stayed. Mama loved watching it pounce on a string and lap milk from a bowl. She loved hearing it purr and worked with me to be gentle with it.

One afternoon, in the driveway, Dad ran over the kitten. Mama could not stop crying.

“He said it was an accident and he was sorry,” Mama told me years later. “But I never believed him.” She jutted out her jaw. “He didn’t want that kitten in the house.”

I find it unlikely that my dad intentionally ran over a kitten. He had a reputation for being soft when it came to killing animals, even to put food on the table. But I do believe some part of their marriage died with that kitten.

When Mama found herself clutching the butcher knife, she said she thought about me and Vicki, what using the knife would mean, how it would carve a different course for each of us. I’ll be forever grateful that Mama fast-forwarded to the consequences in her mind. She released her grip on the handle and chose divorce over murder.

I have only a single flash of memory of leaving Iowa.

I’m sitting on the plush seat of a train, the nappy brocade scratching my thighs. I’m not afraid, because I’m pressed against Mama’s arm; I can feel the warmth of her against my side as she rocks rhythmically. She holds Vicki (who no doubt was sleeping). I repeatedly click my black patent shoes together and apart, together and apart, noticing the folded lace tops of my anklets hanging just over the edge of the cushion. The world is a blur passing by the train window. Clickety-clack. Clickety-clack. Watch your back. We are headed west to Fort Morgan, Colorado.

1950

“I left your Dad,” Mama told me more than once, “because I didn’t want to kill him.”

She wasn’t kidding.

Mama said she stood at the kitchen counter, her hand touching the smooth wooden handle of a butcher knife. In an argument that grew more heated, Mama felt her fist close around the handle. For a brief moment, she deliberated between slashing our father with the knife or releasing it harmlessly back onto the counter and walking away.

My sister Vicki was ten months old; I was two. Mama was seventeen.

By all accounts, Mom and Dad loved one another, even though Mama lied about her age. Mama told my dad that she had celebrated her eighteenth birthday; Dad, twenty-two, believed her. But the State of Iowa insisted on seeing Mama’s record of birth before granting them a marriage license. Only then did Mama confess her lie to my dad. He broke down and cried. Mama was fourteen, not eighteen. Still, despite the deceit and age difference, on Wednesday, May 26, 1948, Carola Jean Simmonds and Donald Lee Skinner said “I do.” Mama’s mother signed her consent.

Mama definitely looked older than fourteen. She had thick black hair that fell around her face, accenting the widow’s peak she inherited from her mother. Her hazel eyes reflected not a shy, timid girl, but held a womanly gaze that belied her years. Physically, she was curved and bosomed. But she was not pregnant. According to my birth certificate, I came along a full eleven months after they married, proving their union sprang from something other than necessity.

Part of Mama’s motivation may have sprung from her eagerness to leave home. Her older brother, my Uncle Gaylen, witnessed the difficult relationship Mama had with their mother.

“This is hard to tell,” he said. “When your mom was just a baby, I remember walking alongside her baby carriage with our mom. I must have been about eight. Carola was crying and crying and Mom got so mad. She stopped the carriage, walked to a nearby tree, and yanked off a switch. She returned to the carriage and whipped your mom for crying. I couldn’t believe she was whipping a baby.”

Uncle Gaylen fumbled for words, attributing his mom’s state of mind to my grandfather Gashum’s infidelity. “I think Mom took out all her frustrations on Carola,” he said.

I wish I could scrub that stain from our family’s history. I wish I could reach back in time, snatch the switch from Grandma’s raised fist, and snap it across my knee. It might have made a difference. Mama’s life might have taken a different turn.

She might not have been so desperate for tenderness.

By the time Mama turned fourteen, she had fallen for my dad. Instead of protesting when Mama asked to marry him, Grandma extolled my father’s family, told Mama she was lucky to have him, and readily signed permission for Mama to marry. With the words “I do” uttered in the sleepy town of Glenwood, Iowa, Mama became a fourteen-year-old tenant farmer’s wife.

Around that time, Mama wrote a couple of jingles and sold them to Burma Shave as part of their road-side advertising campaign. Mama liked to drive by a particular set of red and white signs posted successively along the highway near Glenwood. The words on the signs, which built toward a punchline farther down the road, were Mama’s words, right there in plain daylight, for the whole world to see.

His cheek

Was rough

His chick vamoosed

And now she won’t

Come home to roost

Burma Shave

It’s impossible to know which jingles Mama wrote, but, all her life, she loved the word vamoose.

During the first year of their marriage, my parents moved into a house without running water, off County Road L-45 not far from the Waubonsie Church and Cemetery outside Glenwood. Dad, a farmer, loved the land and spent long hours plowing, planting, and tending the livestock. His mother, my Grandma Skinner, lived four miles down the gravel road. Grandma Skinner had raised six children while slopping the pigs, sewing, planting a garden, canning, baking, and putting hearty meals on the table three times a day. I think Dad assumed all women inherited Grandma’s Hestian gene.

But not his child-bride, Carola Jean. She could write a jingle, but she knew nothing about cooking, gardening, cleaning, or running a household—not even how to iron.

“Your mom couldn’t keep up with the house or the laundry,” Aunt Dixie, my dad’s sister, said years later. “If she ran out of diapers, she’d pin curtains or dishtowels on you, anything she could get her hands on.”

I doubt Mama knew what to do with a screaming colicky baby either, one who smelled of sour milk and required little sleep. In a house without running water, I must have contributed to a legion of laundry and fatigue. The doctor finally determined I suffered from a milk allergy and switched me to soy milk, which cured my colic, but not my aversion to sleep.

“In desperation,” Mama recounted many times, “I scooted your crib close enough to the bed to reach my hand through the slats to hold your hand. Finally you’d settle down, but—” Mama would draw in a long breath here—“if I let go, you’d wake up and start crying all over again. You always wanted to be near me. Sometimes I cried, too.”

Without fail, the next part of her story included a comparison between me and my sister Vicki, born fourteen months later.

“Now, Vicki was just the opposite,” Mama marveled. “I’d have to keep thumping her on her heel just to keep her awake long enough to eat.”

Mama’s retelling of that story during our growing-up years made me feel like thumping Vicki, too, and it had nothing to do with staying awake. I pictured Vicki sleeping peacefully and wished I had been an easier child. More than once I wanted to shout, I can’t help what I did as a baby! But I held my tongue; I was good at that.

By the time Vicki joined our household, we lived in a former rural schoolhouse near Emerson, Iowa. It was here that Mama broke.

She was sixteen.

No matter how you do the math, the equation always comes out the same; Mama was little more than a child herself. The rigors of marriage, farm life, and two girls under the age of two finally came crashing down on her.

Mama had adopted a kitten, much to my delight and my dad’s dismay. Dad did not want animals in the house. But Mama stood her ground; the kitten stayed. Mama loved watching it pounce on a string and lap milk from a bowl. She loved hearing it purr and worked with me to be gentle with it.

One afternoon, in the driveway, Dad ran over the kitten. Mama could not stop crying.

“He said it was an accident and he was sorry,” Mama told me years later. “But I never believed him.” She jutted out her jaw. “He didn’t want that kitten in the house.”

I find it unlikely that my dad intentionally ran over a kitten. He had a reputation for being soft when it came to killing animals, even to put food on the table. But I do believe some part of their marriage died with that kitten.

When Mama found herself clutching the butcher knife, she said she thought about me and Vicki, what using the knife would mean, how it would carve a different course for each of us. I’ll be forever grateful that Mama fast-forwarded to the consequences in her mind. She released her grip on the handle and chose divorce over murder.

I have only a single flash of memory of leaving Iowa.

I’m sitting on the plush seat of a train, the nappy brocade scratching my thighs. I’m not afraid, because I’m pressed against Mama’s arm; I can feel the warmth of her against my side as she rocks rhythmically. She holds Vicki (who no doubt was sleeping). I repeatedly click my black patent shoes together and apart, together and apart, noticing the folded lace tops of my anklets hanging just over the edge of the cushion. The world is a blur passing by the train window. Clickety-clack. Clickety-clack. Watch your back. We are headed west to Fort Morgan, Colorado.