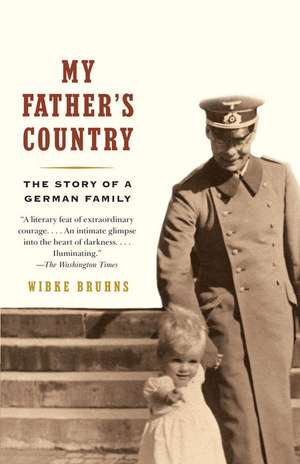

My Father's Country: The Story of a German Family

Autor Wibke Bruhns Traducere de Shaun Whitesideen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2009

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 100.41 lei 6-8 săpt. | |

| Vintage Books USA – 31 iul 2009 | 133.06 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| CORNERSTONE – 7 mar 2016 | 100.41 lei 6-8 săpt. |

Preț: 133.06 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 200

Preț estimativ în valută:

25.47€ • 27.67$ • 21.41£

25.47€ • 27.67$ • 21.41£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 31 martie-14 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400096701

ISBN-10: 1400096707

Pagini: 361

Ilustrații: 8 PP. B&W PHOTOS

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 21 mm

Greutate: 0.37 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 1400096707

Pagini: 361

Ilustrații: 8 PP. B&W PHOTOS

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 21 mm

Greutate: 0.37 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

Wibke Bruhns was born in 1938 in Halberstadt. She has worked as a journalist in both TV and print and as a TV presenter and news reader. She worked as a correspondent for Stern magazine in the United States and Israel and headed the culture section at one of Germany’s largest television stations, ORB. She has two grown daughters and now lives and works as a freelance writer in Berlin.

Extras

I can immerse myself in the early photographs-the half-timbering, the baroque, ramshackle stables, the courtyards. The town had 43,000 inhabitants in 1900, the pictures suggest affluence and above all industry. Shops everywhere, markets, awnings outside the shops. The Kaiserhof patisserie by the fish market served its customers under parasols on a second-floor terrace. From 1887 there was a horse tram, replaced in 1903 by the electric one. From 1888 the people of Halberstadt were able to use the telephone. Charlemagne himself had established the diocese in 804, and even today when I drive across the incredibly flat North German landscape I see churches in the distance, many, many churches.

For me Halberstadt is a metaphor. Halberstadt is "before." My memory of the town where I was born, the town of my early childhood, begins on April 8, 1945, the Sunday after Easter, at 11:25 in the morning. Allied bombers, supposedly 215 of them, reduced 82 percent of the old town to rubble. I was six at the time. All my memories prior to that are buried under ruins, consumed in the conflagration that raged for days. After that I remember a difficult postwar time everywhere and nowhere-that was the beginning of what became my life. Halberstadt isn't part of it. Whenever I drove there later on, what I found was gray, decaying everyday life in East Germany, brightened by family friends, but still strange to me. Today Halberstadt is a pleasure. The town always picks itself up, as it did after the destruction wrought by Henry the Lion, the Peasant War and the Reformation, the Thirty Years' War, French rule, and its storming by the Cossacks.

At some point in the meantime the Klamroths arrived. "For when our forefather came out of the woods near Börnecke in the Harz . . . dapp-i-dee," they sang later at their family parties. The forefather appeared sometime around 1500. Thereafter Klamroths were living in the villages of the Harz mountains as foresters and saddlers to the court of Saxony, master brewers, and even one town councillor in Ermsleben. Things really got intriguing with Johann Gottlieb. He was a trained businessman, he traveled with the certificate of the "Honorable Guild of Grocers and Canvas Tailors" from Quedlinburg to Halberstadt, "at which place" he founded the company I.G. Klamroth in 1790. He was twenty-two; in 1788 he first sealed his letters with the family crest that we still use today.

There was one infallible way for me to put Else in a fury. Like everyone who marries into a family of stature she was a convinced convert: the honor of the Klamroth family was sacred to her. If I compared this family-not inaccurately-with the Buddenbrooks, Else foamed at the mouth. If I described the company-that company!-as a shop selling hop poles and jute bags, there was serious trouble. Yet it's not a completely inaccurate description either.

Johann Gottlieb ran a business selling "fabric and victuals." That was how it started. He wore his hair in the style of Napoleon-how did they do that in those days, long before hairspray was invented? When he got up in the morning, did he look as handsome as he does in his oil painting? How often were the lace ruffs under his velvet collar washed? And did he wear them at the counter? We don't really know anything.

In 1802 he married sensibly into a flourishing leather company. His wife's father had passed away, and Johann Gottlieb moved his business into his late father-in-law's residence at No. 3 An der Woort-"house fit for a brewery, with 5 large rooms, 8 smaller rooms, 2 alcoves, 1 plaster and 2 tiled floors and 2 vaulted cellars, valued at a total of 2,011 thaler 14 groschen." It was in the ruins of this glorious building, frequently rebuilt and finally flattened, that the company continued to vegetate after the Second World War.

For Johann Gottlieb and his vivacious wife, Frau Johanne, things went from strength to strength. There were no paralyzing guild regulations; instead there was freedom of trade. The peasants were liberated in 1807 by Friedrich Wilhelm III and his Baron von Stein. Somehow, herring barrels and dibbles were no longer of the moment. The trade now moved to peas and wheat, poppy seeds and hemp, far beyond the boundaries of Halberstadt. Industry! It's a joy to follow the traces of these early family entrepreneurs, who efficiently absorbed each economic change, spotted each innovation on the horizon just in time, and converted it into profit.

In 1828, at the age of twenty-five, Johann Gottlieb's son Louis joined the company. He was as ugly as sin and a gifted businessman. With various different partners and a complex network of companies, he sold seeds imported from all over Europe, agricultural implements, grains, and fertilizer. In his own factories he produced beet sugar, spirits, and vinegar; he traded in cement, wine, and even money. His flourishing pawnbroker's firm bought its customers' family jewels for good cash and gave them credit on favorable terms.

Louis bought farmland that he leased out to his own factories for the planting of sugar beet. He owned houses, properties, farms, and a manor. His transport company carried goods from the new railway to the buyer; agricultural products were stacked up in warehouses for sale even beyond the boundaries of Prussia. He was one of the first to equip his factories and farms with new steam-operated machinery, sowing machines, and harvesters-Louis was heavily into the new technology. By 1840 he had in his private office a desk with a built-in copying press of which he was particularly proud, because it meant that he didn't have to have his letters copied out by his apprentices.

Louis Klamroth advised the region's farmers of the advantages of Victoria or giant-yield peas ("a yield of 16-18 Berliner Scheffel"-about fifty-five liters-"per Magdeburg acre, the softer, longer straw is very healthy feed for cattle"), and Hungarian seed corn ("has proven in our last harvest to be ideal for our climatic conditions"). He included "red clover, green fescue, and timothy grass" in his assortment, and sold "English riddles," coarse-meshed sieves for separating wheat and chaff.

In his youth, Louis traveled on horseback to visit business colleagues in Leipzig and Frankfurt am Main, finding the express post chaise too slow. On these journeys he carried large sums of money in a belt wrapped around his body. It hasn't been recorded whether he carried a weapon as well, but horse riding has stayed in the family. In 1861 Louis Klamroth-his actual name was Wilhelm Ludwig-was appointed to the Royal Prussian Chamber of Commerce, and when he died twenty years later he left a princely fortune. Holding in my hands the will that he drew up together with his wife, Bertha, I was impressed. Even their young granddaughter Martha Löbbecke, whose mother had died in childbirth, was promised 330,000 marks, a vast sum of money at that time-and their son Gustav, Louis's successor in the company, paid the sum in a single installment. Gustav was also able to perform a similar service for his three living brothers and sisters, and nowhere is there any suggestion that these disbursements brought the company to its knees.

Gustav is educated like a crown prince--a year at the renowned Beyersches Trade Institute in Braunschweig, a four-year apprenticeship with the import-export business of the von Fischers in Bremen, extended internships with companies in London and Paris. Finally in 1861, at the age of twenty-four, he becomes a partner in the firm. New brooms sweep clean, and like his father before him, Gustav now seeks to ensure that an already impressive business grows even bigger.

Gustav admires the chemist Justus von Liebig, who revolutionized agriculture with his artificial fertilizer. After less than three years with the company, and much earlier than his hesitant competitors, Klamroth junior begins manufacturing superphosphates, which would very swiftly lead to the establishment of an extremely profitable fertilizer factory in Nienburg an der Weser. The Liebig label was still a presence in my childhood: in my parents' library there were imposing albums of pictures collected from Liebig's meat extract packages, and everything I know about the legend of King Arthur or the battle of Königgrätz I have gleaned from these trading cards.

The 1866 war--Prussia versus the rest of the German-speaking world--was resolved in Königgrätz after just four weeks. In those days wars tended not to last very long. Two or three big battles--I imagine them as being something like a soccer final, with brightly colored uniforms, foaming horses, banners, flags. On the com-manders' mound Wilhelm I and his leather-faced General Helmuth von Moltke. "March apart, strike together," was his credo: three Prussian armies came from different directions, to the bafflement of the Austrians and the Saxons.

Things got going on July 3, 1866. The different sides lined up in the open field-the town of Königgrätz was a long way from the tumult-a trumpet sounded, and a murderous clanging of weaponry began and lasted till evening, when messengers on horseback appeared with white flags and the horrors were over. A single day. That was it. At least that was how "the greatest battle of the century," as it has since come to be known, was told in Liebig's meat extract pictures.

There was great agitation at I.G. Klamroth. The kingdom of Hanover had sided with Austria against Prussia, and relations between Prussian Halberstadt and Nienburg in Hanover were difficult. Banks had stopped credit, imports from England were being held on the River Weser, trains weren't allowed to cross the border, which was guarded with great suspicion by the Cuirassiers of Halberstadt. Louis and young Gustav walked about with concerned expressions, while packages for Bohemia were assembled at the company's headquarters, and workers picked rags for lint. But then Hanover was swallowed up by Prussia, and soon everyone was friends again.

Bismarck's North German Alliance was formed, and trade barriers fell-a blessing for business. Gustav made use of whatever could be used: steam-driven plows were brought in, there was a steam thresher, Gustav's wife, Anna, was given-long before it turned into an industry-a mechanical sewing machine. But Gustav was useful to others, too: in 1867 he became a town councillor, and remained so until 1904. He oversaw the foundation of the Halberstadt Chamber of Commerce, and became its second chairman. He represented the interests of Halberstadt in the provincial parliament and the provincial council, and he was an active member of the National Liberal Party, for many years one of Bismarck's chief parliamentary supports.

Gustav donated stained-glass windows to the reformed Liebfrauenkirche in Halberstadt, and a magnificent banner to the local grammar school, the Königliches Domgymnasium. He bought a large plot of land for a new imperial post office, donated a convalescent home to what would later become St. Cecilia's convent, and financed the building of the infant school. He was on the committee of the Fatherland Women's Association-what was he doing there?-the Shelter to Home Association-whatever that was?-and the Halberstadt Art Society. For the company's one hundredth anniversary in 1890, the town was given 30,000 marks to establish a Klamroth Memorial Foundation for distressed businessfolk, and Gustav was awarded the additional honorary title of Königlicher Kommerzienrath, or councillor of commerce.

He was a very kind man. Even the late photographs showing him as a patriarch, taken around the turn of the century, give a sense of the warmth that he radiated around his wife and the five surviving children. In Gustav's accounts you constantly come across special gifts, presents, and rewards for the company employees and the family's domestic staff. There was always some member of the extended family who was ill, and Frau Anna describes her husband wandering comfortingly around the house at night with babies in his arms. Two of the couple's sons died very young, and in Gustav's household accounts book I found an entry for 1868, under the heading "miscellaneous," mentioning 2 thaler 15 silver groschen for a child's coffin. The cross for Johannes Gott-fried's grave cost 25 thaler. Gustav's wife, Anna, had the following words for her son inscribed on it:

Short was your life, beloved,

But filled with pain and woe,

Rest in the peace of God,

You dearest little soul.

Anna was profoundly religious, yet despite her grief over her dead sons and her own serious illnesses, she was a very cheerful woman. She wrote enchanting children's stories in her picturesque handwriting, preserved in four well-tended leather volumes, and also love poems to Gustav. When she fell dangerously ill once again, she allowed him to weep tears of despair in the event of her death, but asked:

When you have granted pain its rights,

Come back, rejoin your life,

And give the children soon a mother;

Choose yourself a wife.

Man should not walk lonely on the earth,

A true heart should be by your side.

In time one spring succeeds another

And in time you shall have a new bride.

She was just fifty years old when she died in 1890, and Gustav did not replace her. He lived alone for another fifteen years, looked after and admired by his children, his friends, and the dignitaries of the town, an intelligent man and a sagacious voice of caution, who was worried to see Bismarck, the "Chancellor of Peace," deposed by Wilhelm II. Husband and wife had celebrated the foundation of the Reich in 1871; when the victorious troops returned, the euphoria in Halberstadt was uncontainable, too. Anna's lines on the welcoming of the Halberstadt Cuirassiers were sung in every street: "High flies the banner, in wild, warlike dance; onward, bold horsemen, to victory advance."

Business was thriving. At I.G. Klamroth, things were consolidated and expanded. The Company Chronicle, published in 1908, records soaring profits from 1871 until 1880, the company having been spared the serious downturns that affected many firms in the early years of the Reich. Its author, Gustav's son and successor, Kurt, enthusiastically describes "the foundation of the German Reich, which with its patriotic verve roused all the slumbering powers of the national economy." Because, he continued, "the five billion of 1871"-referring to the war reparations demanded from France, a fresh spur for Franco-German hostility-"was, so to speak, the oil with which the rigid masses of the national workforce were transformed into living power, they set the big machine in motion and now it's working at full steam." May Kurt be forgiven. He had spent the first half of his life in a state of national drama. He was sixteen in 1888, when Wilhelm II ascended the throne-how could he have been any different?

I become aware that I'm gradually approaching the pain threshold. On the way to Hans Georg I would have liked still to linger with Louis and Gustav, to wander around that wonderful era in this cool Prussia, when the world was laid out in front of the forebears like a ripe field of sugar beet. If you had done your homework, all you needed to do was reap the harvest.

From the Hardcover edition.

For me Halberstadt is a metaphor. Halberstadt is "before." My memory of the town where I was born, the town of my early childhood, begins on April 8, 1945, the Sunday after Easter, at 11:25 in the morning. Allied bombers, supposedly 215 of them, reduced 82 percent of the old town to rubble. I was six at the time. All my memories prior to that are buried under ruins, consumed in the conflagration that raged for days. After that I remember a difficult postwar time everywhere and nowhere-that was the beginning of what became my life. Halberstadt isn't part of it. Whenever I drove there later on, what I found was gray, decaying everyday life in East Germany, brightened by family friends, but still strange to me. Today Halberstadt is a pleasure. The town always picks itself up, as it did after the destruction wrought by Henry the Lion, the Peasant War and the Reformation, the Thirty Years' War, French rule, and its storming by the Cossacks.

At some point in the meantime the Klamroths arrived. "For when our forefather came out of the woods near Börnecke in the Harz . . . dapp-i-dee," they sang later at their family parties. The forefather appeared sometime around 1500. Thereafter Klamroths were living in the villages of the Harz mountains as foresters and saddlers to the court of Saxony, master brewers, and even one town councillor in Ermsleben. Things really got intriguing with Johann Gottlieb. He was a trained businessman, he traveled with the certificate of the "Honorable Guild of Grocers and Canvas Tailors" from Quedlinburg to Halberstadt, "at which place" he founded the company I.G. Klamroth in 1790. He was twenty-two; in 1788 he first sealed his letters with the family crest that we still use today.

There was one infallible way for me to put Else in a fury. Like everyone who marries into a family of stature she was a convinced convert: the honor of the Klamroth family was sacred to her. If I compared this family-not inaccurately-with the Buddenbrooks, Else foamed at the mouth. If I described the company-that company!-as a shop selling hop poles and jute bags, there was serious trouble. Yet it's not a completely inaccurate description either.

Johann Gottlieb ran a business selling "fabric and victuals." That was how it started. He wore his hair in the style of Napoleon-how did they do that in those days, long before hairspray was invented? When he got up in the morning, did he look as handsome as he does in his oil painting? How often were the lace ruffs under his velvet collar washed? And did he wear them at the counter? We don't really know anything.

In 1802 he married sensibly into a flourishing leather company. His wife's father had passed away, and Johann Gottlieb moved his business into his late father-in-law's residence at No. 3 An der Woort-"house fit for a brewery, with 5 large rooms, 8 smaller rooms, 2 alcoves, 1 plaster and 2 tiled floors and 2 vaulted cellars, valued at a total of 2,011 thaler 14 groschen." It was in the ruins of this glorious building, frequently rebuilt and finally flattened, that the company continued to vegetate after the Second World War.

For Johann Gottlieb and his vivacious wife, Frau Johanne, things went from strength to strength. There were no paralyzing guild regulations; instead there was freedom of trade. The peasants were liberated in 1807 by Friedrich Wilhelm III and his Baron von Stein. Somehow, herring barrels and dibbles were no longer of the moment. The trade now moved to peas and wheat, poppy seeds and hemp, far beyond the boundaries of Halberstadt. Industry! It's a joy to follow the traces of these early family entrepreneurs, who efficiently absorbed each economic change, spotted each innovation on the horizon just in time, and converted it into profit.

In 1828, at the age of twenty-five, Johann Gottlieb's son Louis joined the company. He was as ugly as sin and a gifted businessman. With various different partners and a complex network of companies, he sold seeds imported from all over Europe, agricultural implements, grains, and fertilizer. In his own factories he produced beet sugar, spirits, and vinegar; he traded in cement, wine, and even money. His flourishing pawnbroker's firm bought its customers' family jewels for good cash and gave them credit on favorable terms.

Louis bought farmland that he leased out to his own factories for the planting of sugar beet. He owned houses, properties, farms, and a manor. His transport company carried goods from the new railway to the buyer; agricultural products were stacked up in warehouses for sale even beyond the boundaries of Prussia. He was one of the first to equip his factories and farms with new steam-operated machinery, sowing machines, and harvesters-Louis was heavily into the new technology. By 1840 he had in his private office a desk with a built-in copying press of which he was particularly proud, because it meant that he didn't have to have his letters copied out by his apprentices.

Louis Klamroth advised the region's farmers of the advantages of Victoria or giant-yield peas ("a yield of 16-18 Berliner Scheffel"-about fifty-five liters-"per Magdeburg acre, the softer, longer straw is very healthy feed for cattle"), and Hungarian seed corn ("has proven in our last harvest to be ideal for our climatic conditions"). He included "red clover, green fescue, and timothy grass" in his assortment, and sold "English riddles," coarse-meshed sieves for separating wheat and chaff.

In his youth, Louis traveled on horseback to visit business colleagues in Leipzig and Frankfurt am Main, finding the express post chaise too slow. On these journeys he carried large sums of money in a belt wrapped around his body. It hasn't been recorded whether he carried a weapon as well, but horse riding has stayed in the family. In 1861 Louis Klamroth-his actual name was Wilhelm Ludwig-was appointed to the Royal Prussian Chamber of Commerce, and when he died twenty years later he left a princely fortune. Holding in my hands the will that he drew up together with his wife, Bertha, I was impressed. Even their young granddaughter Martha Löbbecke, whose mother had died in childbirth, was promised 330,000 marks, a vast sum of money at that time-and their son Gustav, Louis's successor in the company, paid the sum in a single installment. Gustav was also able to perform a similar service for his three living brothers and sisters, and nowhere is there any suggestion that these disbursements brought the company to its knees.

Gustav is educated like a crown prince--a year at the renowned Beyersches Trade Institute in Braunschweig, a four-year apprenticeship with the import-export business of the von Fischers in Bremen, extended internships with companies in London and Paris. Finally in 1861, at the age of twenty-four, he becomes a partner in the firm. New brooms sweep clean, and like his father before him, Gustav now seeks to ensure that an already impressive business grows even bigger.

Gustav admires the chemist Justus von Liebig, who revolutionized agriculture with his artificial fertilizer. After less than three years with the company, and much earlier than his hesitant competitors, Klamroth junior begins manufacturing superphosphates, which would very swiftly lead to the establishment of an extremely profitable fertilizer factory in Nienburg an der Weser. The Liebig label was still a presence in my childhood: in my parents' library there were imposing albums of pictures collected from Liebig's meat extract packages, and everything I know about the legend of King Arthur or the battle of Königgrätz I have gleaned from these trading cards.

The 1866 war--Prussia versus the rest of the German-speaking world--was resolved in Königgrätz after just four weeks. In those days wars tended not to last very long. Two or three big battles--I imagine them as being something like a soccer final, with brightly colored uniforms, foaming horses, banners, flags. On the com-manders' mound Wilhelm I and his leather-faced General Helmuth von Moltke. "March apart, strike together," was his credo: three Prussian armies came from different directions, to the bafflement of the Austrians and the Saxons.

Things got going on July 3, 1866. The different sides lined up in the open field-the town of Königgrätz was a long way from the tumult-a trumpet sounded, and a murderous clanging of weaponry began and lasted till evening, when messengers on horseback appeared with white flags and the horrors were over. A single day. That was it. At least that was how "the greatest battle of the century," as it has since come to be known, was told in Liebig's meat extract pictures.

There was great agitation at I.G. Klamroth. The kingdom of Hanover had sided with Austria against Prussia, and relations between Prussian Halberstadt and Nienburg in Hanover were difficult. Banks had stopped credit, imports from England were being held on the River Weser, trains weren't allowed to cross the border, which was guarded with great suspicion by the Cuirassiers of Halberstadt. Louis and young Gustav walked about with concerned expressions, while packages for Bohemia were assembled at the company's headquarters, and workers picked rags for lint. But then Hanover was swallowed up by Prussia, and soon everyone was friends again.

Bismarck's North German Alliance was formed, and trade barriers fell-a blessing for business. Gustav made use of whatever could be used: steam-driven plows were brought in, there was a steam thresher, Gustav's wife, Anna, was given-long before it turned into an industry-a mechanical sewing machine. But Gustav was useful to others, too: in 1867 he became a town councillor, and remained so until 1904. He oversaw the foundation of the Halberstadt Chamber of Commerce, and became its second chairman. He represented the interests of Halberstadt in the provincial parliament and the provincial council, and he was an active member of the National Liberal Party, for many years one of Bismarck's chief parliamentary supports.

Gustav donated stained-glass windows to the reformed Liebfrauenkirche in Halberstadt, and a magnificent banner to the local grammar school, the Königliches Domgymnasium. He bought a large plot of land for a new imperial post office, donated a convalescent home to what would later become St. Cecilia's convent, and financed the building of the infant school. He was on the committee of the Fatherland Women's Association-what was he doing there?-the Shelter to Home Association-whatever that was?-and the Halberstadt Art Society. For the company's one hundredth anniversary in 1890, the town was given 30,000 marks to establish a Klamroth Memorial Foundation for distressed businessfolk, and Gustav was awarded the additional honorary title of Königlicher Kommerzienrath, or councillor of commerce.

He was a very kind man. Even the late photographs showing him as a patriarch, taken around the turn of the century, give a sense of the warmth that he radiated around his wife and the five surviving children. In Gustav's accounts you constantly come across special gifts, presents, and rewards for the company employees and the family's domestic staff. There was always some member of the extended family who was ill, and Frau Anna describes her husband wandering comfortingly around the house at night with babies in his arms. Two of the couple's sons died very young, and in Gustav's household accounts book I found an entry for 1868, under the heading "miscellaneous," mentioning 2 thaler 15 silver groschen for a child's coffin. The cross for Johannes Gott-fried's grave cost 25 thaler. Gustav's wife, Anna, had the following words for her son inscribed on it:

Short was your life, beloved,

But filled with pain and woe,

Rest in the peace of God,

You dearest little soul.

Anna was profoundly religious, yet despite her grief over her dead sons and her own serious illnesses, she was a very cheerful woman. She wrote enchanting children's stories in her picturesque handwriting, preserved in four well-tended leather volumes, and also love poems to Gustav. When she fell dangerously ill once again, she allowed him to weep tears of despair in the event of her death, but asked:

When you have granted pain its rights,

Come back, rejoin your life,

And give the children soon a mother;

Choose yourself a wife.

Man should not walk lonely on the earth,

A true heart should be by your side.

In time one spring succeeds another

And in time you shall have a new bride.

She was just fifty years old when she died in 1890, and Gustav did not replace her. He lived alone for another fifteen years, looked after and admired by his children, his friends, and the dignitaries of the town, an intelligent man and a sagacious voice of caution, who was worried to see Bismarck, the "Chancellor of Peace," deposed by Wilhelm II. Husband and wife had celebrated the foundation of the Reich in 1871; when the victorious troops returned, the euphoria in Halberstadt was uncontainable, too. Anna's lines on the welcoming of the Halberstadt Cuirassiers were sung in every street: "High flies the banner, in wild, warlike dance; onward, bold horsemen, to victory advance."

Business was thriving. At I.G. Klamroth, things were consolidated and expanded. The Company Chronicle, published in 1908, records soaring profits from 1871 until 1880, the company having been spared the serious downturns that affected many firms in the early years of the Reich. Its author, Gustav's son and successor, Kurt, enthusiastically describes "the foundation of the German Reich, which with its patriotic verve roused all the slumbering powers of the national economy." Because, he continued, "the five billion of 1871"-referring to the war reparations demanded from France, a fresh spur for Franco-German hostility-"was, so to speak, the oil with which the rigid masses of the national workforce were transformed into living power, they set the big machine in motion and now it's working at full steam." May Kurt be forgiven. He had spent the first half of his life in a state of national drama. He was sixteen in 1888, when Wilhelm II ascended the throne-how could he have been any different?

I become aware that I'm gradually approaching the pain threshold. On the way to Hans Georg I would have liked still to linger with Louis and Gustav, to wander around that wonderful era in this cool Prussia, when the world was laid out in front of the forebears like a ripe field of sugar beet. If you had done your homework, all you needed to do was reap the harvest.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“A literary feat of extraordinary courage. . . . An intimate glimpse into the heart of darkness. . . . Illuminating.”

—The Washington Times

“A clear-eyed portrait of a flawed man living in complex-and nightmarish-times.”

—Newsday

“In a time of bogus memoirs that, when exposed to air, crumble before Oprah's baleful glare, My Father's Country is the genuine article.”

—Chicago Sun-Times

“Fascinating. . . . For anyone interested in the German psyche between the wars . . . [this] should be compelling reading.”

—Providence Journal

“A searing, painful inquiry.... Riveting and heartbreaking.”

—Booklist

—The Washington Times

“A clear-eyed portrait of a flawed man living in complex-and nightmarish-times.”

—Newsday

“In a time of bogus memoirs that, when exposed to air, crumble before Oprah's baleful glare, My Father's Country is the genuine article.”

—Chicago Sun-Times

“Fascinating. . . . For anyone interested in the German psyche between the wars . . . [this] should be compelling reading.”

—Providence Journal

“A searing, painful inquiry.... Riveting and heartbreaking.”

—Booklist

Descriere

Descriere de la o altă ediție sau format:

Decades later, watching a documentary about the events of 20 July, images of her father in the Third Reich People's Court appeared on the screen - and she realises she never knew him.In My Father's Country, Bruhns tells of her search for her father.

Decades later, watching a documentary about the events of 20 July, images of her father in the Third Reich People's Court appeared on the screen - and she realises she never knew him.In My Father's Country, Bruhns tells of her search for her father.