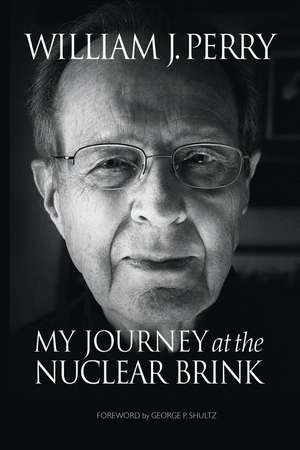

My Journey at the Nuclear Brink

Autor William Perryen Limba Engleză Paperback – 10 noi 2015

In a remarkable career, Perry has dealt firsthand with the changing nuclear threat. Decades of experience and special access to top-secret knowledge of strategic nuclear options have given Perry a unique, and chilling, vantage point from which to conclude that nuclear weapons endanger our security rather than securing it.

This book traces his thought process as he journeys from the Cuban Missile Crisis, to crafting a defense strategy in the Carter Administration to offset the Soviets' numeric superiority in conventional forces, to presiding over the dismantling of more than 8,000 nuclear weapons in the Clinton Administration, and to his creation in 2007, with George Shultz, Sam Nunn, and Henry Kissinger, of the Nuclear Security Project to articulate their vision of a world free from nuclear weapons and to lay out the urgent steps needed to reduce nuclear dangers.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (1) | 172.50 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| Stanford University Press – 10 noi 2015 | 172.50 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| Hardback (1) | 645.98 lei 6-8 săpt. | |

| Stanford University Press – 10 noi 2015 | 645.98 lei 6-8 săpt. |

Preț: 172.50 lei

Nou

33.01€ • 34.62$ • 27.48£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 11-25 martie

Specificații

ISBN-10: 0804797129

Pagini: 276

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.39 kg

Editura: Stanford University Press

Colecția Stanford Security Studies

Recenzii

"In clear, detailed but powerful prose, Perry's new book, My Journey at the Nuclear Brink, tells the story of his seventy-year experience of the nuclear age. Beginning with his firsthand encounter with survivors living amid 'vast wastes of fused rubble' in the aftermath of World War II, his account takes us up to today when Perry is on an urgent mission to alert us to the dangerous nuclear road we are traveling."—Jerry Brown, The New York Review of Books

Notă biografică

Cuprins

This chapter underscores the enormous danger of nuclear weapons, especially in conditions of hostility and noncooperation among nuclear powers, by recounting the Cuban Missile Crisis. It shows that the world neared a nuclear holocaust, threatening civilization itself. A member of the analysis team providing daily crisis reports to President Kennedy and his advisors, Perry, contrary to public post mortems on the crisis, reflects that catastrophe was averted as much by luck as by successful crisis management. US decision makers' knowledge was imperfect and sometimes wrong. Some local commanders had discretion to begin armed conflict and nearly did. Operational mistakes as well as normal military activities elsewhere in the world could have been interpreted as a nuclear attack. It is shown that there was no precedent for resolving the risk of history's gravest war. Perry decides to pursue a career mitigating the nuclear threat.

This chapter recounts Perry's experiences as a young soldier in the Army of Occupation in Japan just after the end of World War II, and shows how he began to change his thinking about national security in the era of nuclear weapons as well as his thinking about his own calling. The devastation he witnesses in Tokyo and Naha, together with the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, "changed everything" and demands new modes of thinking about national security. After discharge from the Army, Perry marries, begins a family, and pursues degrees in mathematics, possibly as a prelude to an academic career, but the Korean War and the onset of the Cold War with its nuclear arsenals and "overkill" in increasingly destructive nuclear weapons lead him into defense work, specifically the pioneering of a powerful new reconnaissance capability to curtail miscalculations of Soviet nuclear weapons and catastrophic decisions.

This chapter dramatizes the development of a sophisticated US reconnaissance capability to monitor the secretive Soviet missile and space program during the nuclear arms build-up in the Cold War. Although it could not guarantee deterrence of a catastrophic war, knowledge of the size, deployment, and performance characteristics of the USSR nuclear weapons lent perspective and lessened the danger of miscalculation in an era of concern over the threat of a Soviet nuclear first-strike. Perry begins work at a defense company and studies countermeasures against Soviet missiles, assesses that defense against an attacking nuclear force is ineffective, and becomes a member of the high-ranking government Telemetry and Beacon Analysis Committee (TEBAC) charged with determining the overall Soviet nuclear threat and decides to start a new company, ESL, devoted exclusively to the Cold War reconnaissance mission.

This chapter describes the formation and strong growth of ESL, Inc. beginning in the 1960s in Silicon Valley, Perry's pioneering company in developing sophisticated Cold War reconnaissance capabilities exploiting new digital technology. Special lessons Perry learned about management and cooperation in a successful enterprise of mitigating the danger from nuclear weapons are analyzed, lessons that carried over to his later career beyond the corporate in pursuing that quest. Of ESL's large base of projects, emphasis is placed on intercepting telemetry of Soviet ICBM tests and obtaining signals intelligence on Soviet ballistic missile defense (BMD) systems together with data interpretation, including the often highly innovative measures needed to intercept the data. The chapter also describes Perry's involvement with the US Arms Control and Disarmament Agency in its foundational work at the dawn of the crucial period of arms reduction agreements with the Soviets.

This chapter chronicles Perry's move from corporate life to government service in his journey at the nuclear brink. As undersecretary of defense for research and engineering in the Carter administration, Perry now found himself charged with revolutionizing US tactical battlefield capabilities to offset the Soviet numerical advantage in conventional forces, an advantage threatening nuclear deterrence now that the Soviets had reached nuclear parity with the US. Perry's expertise in digital technology brought him to this role, and he proceeded to assemble a powerful team, most notably Air Force Lt. Col Paul Kaminski as his personal assistant, to meet the immense challenge of upgrading US systems, a challenge that meant exploiting state-of-the-art technology, performing innovations much more quickly than ordinarily done in military weapon development, and "getting things right the first time." Perry gained his initial experience in international diplomacy, an experience crucial in his later career.

This chapter describes implementation of the Offset Strategy to shore-up and strengthen nuclear deterrence. A crucial US accomplishment in the age of nuclear weapons, this development of the "system of systems"¿stealth, smart sensors, smart weapons¿made the US battlefield performance superior and remains the foundation of our premiere military forces, with the later Desert Storm campaign serving as a convincing proving ground for its success. The "force multiplier" effects of the new technology are immensely efficient and economical: even when numerically inferior, US forces can prevail by striking targets with great accuracy while experiencing exceedingly low losses in their own forces and equipment. The Offset Strategy showed the power of revolutionary technology to create conditions of enhanced nuclear deterrence and to point the way to mitigating future dangers, as well as the ability of smart and talented people to respond to the issue of deterrence.

This chapter recounts the buildup of US nuclear forces¿bombers, SLBMs and ICBMs¿led by Perry as undersecretary of defense. Soviet nuclear forces had improved, raising concerns of weakening deterrence and new US vulnerability, especially with the aging of our deployed nuclear triad.Perry rescued the faltering Trident submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) program to replace the aging US Polaris fleet and insured deployment of a superb upgraded force. He extended the lifetime of the US B-52 bomber force against the huge buildup in Soviet air defense by introducing air-launched cruise missiles (ALCMs) fired from B-52s well outside the reach of Soviet air defense systems. Improving the third leg of the triad, essentially the creation of a basing scheme for the new MX ICBM, a problem Perry inherited, was never resolved then or in future administrations, after which the MX was retired.

This chapter shows an example of the awesome danger of nuclear miscalculation and the need for arms control agreements as a means of dialog between nuclear powers, thereby enhancing security through a context of mutual understanding. Perry describes the sudden alert he received as under secretary in the middle of the night on November 9, 1979, when the watch officer at NORAD (North American Air Defense Command) reported his warning computer showed 200 Soviet missiles approaching the US. Although it was a false alarm caused by human error, Perry reflects on the fearsome difficulties of making rational assessments under such duress. This chapter also describes early US-Soviet strategic arms agreements¿the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaties (SALT I and II), their politics and technical evolution¿and missed opportunities to limit proliferation to other countries.

This chapter describes Perry's activities in diplomacy as undersecretary, experiences vital in his later career in seeking cooperative international measures to mitigate the danger of nuclear weapons. Perry recounts his diplomatic mission to China to implement President Carter's initiative to improve China's conventional military forces as one of the means of containment of the USSR, an initiative cancelled after the Tiananmen Square massacre. The chapter also describes Perry's policy to improve the battlefield capabilities of NATO, and thereby enhance deterrence of a nuclear war, through cooperative defense acquisition programs and enhanced interoperability of the weapons of NATO members and hence their ability to operate jointly in combat operations. Perry also reflects on the lessons learned about international cooperation through his exposure to, and participation in aspects of, the Camp David Accords among Israel, Egypt, and the US.

This chapter describes Perry's return to civilian life and his continuing quest to reduce the nuclear danger. His work with the San Francisco investment banker, Hambrecht & Quist, specializing in venture capital support of entrepreneurial high technology companies, is recalled, together with his professorship at Stanford University teaching a popular course on the history of technology in defense. Perry becomes a prominent critic of the Strategic Defense Initiative as unworkable. He undertakes Track 2 diplomacy, designed to open the way for formal government initiatives on reducing the nuclear danger and which takes him to the USSR and other nations, gaining him contacts valuable in his later diplomacy as secretary of defense. As the Soviet Union breaks apart, Perry joins Senators Sam Nunn and Richard Lugar, Harvard professor Ash Carter, and others to develop the Nunn-Lugar legislation to remove "loose nukes" from former Soviet republics.

This chapter describes Perry's return to government service as deputy defense secretary in the first term of the Clinton Administration. The challenge of removing "loose nukes" from former Soviet republics was paramount for Perry in his general quest to prevent the use of nuclear weapons and was a prime motive in his return to the Pentagon. He also considered defense acquisition reform essential to fielding a nimble military, an imperative for maintaining nuclear deterrence in a volatile and dangerous international order, and was determined to carry out a reform program. The chapter relates Perry's successful efforts to fund the Nunn-Lugar program to deal with "loose nukes" and his assembling of an effective team to carry out the work, as well as his forming an experienced and effective senior management team in the Pentagon to lead the defense acquisition reforms.

This chapter describes the work of Perry and colleagues to develop agreements to remove "loose nukes" in former Soviet republics, for example, through the Trilateral Statement and the later agreement it foreshadowed, the Budapest Memorandum, which addressed Ukrainian concerns about the sanctity of its borders. The chapter then turns to events leading up to Perry's confirmation as Secretary of Defense to succeed Les Aspin after he had been asked to step down by President Clinton. Perry relates his discussions with President Clinton and Vice President Gore, the latter crucial in his decision to accept the position. The chapter describes the press conference President Clinton held to announce Perry's appointment and the resultant process of Perry's unanimous confirmation by the Senate. Perry's swearing in ceremony is described.

This chapter describes the dismantling of nuclear weapon systems under the Nunn-Lugar initiative. First-hand accounts of the dismantling activity at weapon sites such as Pervomaysk in Ukraine as well as at military bases in the US are detailed. The broad reach of Nunn-Lugar to include control of fissionable material is indicated together with the provisions for removal of chemical weapons. Perry describes the technical aspects of the dismantling and removal of ICBMs, ICBM silos, nuclear submarines, and strategic bombers. More broadly, he reflects on the remarkable significance of the Nunn-Lugar legislation as a signature development in the nuclear era to support the reduction of the danger from nuclear weapons. Key contributions to the success of Nunn-Lugar by the principal people in the program are called out.

This chapter describes dealing with North Korea in a crisis brought on during Perry's days as defense secretary by that country's move toward nuclear weapons. North Korea was a member of the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty and had agreed to International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) inspections to confirm compliance. Perry recounts how North Korea had prospects of using spent fuel from its "peaceful" reactor at Yongbon in a covert nuclear weapon program, and how the nation suspiciously was threatening to withdraw from the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty and was blocking IAEA inspections. Perry describes his interaction with General Luck, the US commander in South Korea, and his discussions with President Clinton and US officials about US options. The chapter chronicles how the crisis was averted through firm coercive diplomacy and the work of former President Carter in meeting directly with the North Koreans in Pyongyang.

This chapter describes the problems and prospects of ratifying the START II arms control treaty with the Russians, a goal set by President Clinton. Perry recounts the challenging processes in obtaining legislative approval in both the US and Russia for ratification, including his unprecedented address to the Russian Duma spelling out the advisability of ratification, and discusses the lengthy process of ratification in Russia. The chapter also describes the efforts of Perry and others to obtain ratification of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, and chronicles the ultimate failure to do so in the US Senate. Perry reflects on the detriment to efforts to reduce the danger of nuclear weapons by political failures to realize successful arms control initiatives. He analyzes the problems in old modes of thinking in the nuclear era with its demand for innovative, cooperative solutions.

This chapter, pivotal in Perry's journey, dramatizes the failure to balance competing interests among the Cold War foes in Europe in the postwar era of reduced tensions and greater opportunities for cooperation. A natural pull had arisen among NATO nations and the former Soviet republics and Warsaw Pact for working together on regional interests such as peacekeeping in Bosnia. The Partnership for Peace was instituted, a process for previous enemies of NATO to join the alliance, all eager to do so. Perry chronicles the unfortunate politics that ultimately rushed a premature enlargement of NATO, an unenlightened outcome that insufficiently accounted for traditional Russian concerns and soured what were becoming much improved relations with Russia, to the detriment of prospects for greater cooperation on nuclear issues.

This chapter describes the raising of concerns for Western Hemispheric security in the post Cold War world when the danger from nuclear weapons began to grow global and US national security concerns broadened, certainly to include contingencies close to home. It was an enlargement of focus beyond previous practices in the Defense Department. The need was especially dramatized when a military junta overthrew the democratically elected government in Haiti. Perry recounts the superb US military intervention planning that convinced the coup leaders to step aside for a peaceful resolution in Haiti and the restoration of the legitimate leader. In addition, other initiatives by Perry to enhance Western hemispheric security are described, such as regularly scheduled meetings of all hemispheric defense ministers and establishment of a center for hemispheric defense studies (later renamed the William J. Perry Center for Hemispheric Studies).

This chapter describes a major initiative of Perry: instituting policies and procedures to enhance the quality of life of enlisted soldiers and their families, the key principle being the "iron logic" linking a successful quality of life to the superior military capability of our forces. Perry recounts the very successful program he established to allow him direct contact with enlisted personnel in all services at many bases and installations to hear firsthand their concerns and suggestions. Perry describes an innovative program to enlist commercial building contractors to conduct successful business by building greatly improved base housing, a program continuing today. Perry's wife, Lee, extended the humanitarian philosophy to Albania by recommending that State National Guards take their summer tour there to improve greatly an underfunded military hospital, for which she received the Mother Teresa Medal from the president of Albania.

This chapter describes Perry's transition from secretary of defense to civilian life. After carefully considering the decision, Perry, now 70, opted to return to California after one term in the cabinet role, satisfied that he had met goals and objectives, certainly including the compliment that he had been "the GI's general" as reflected by a touching special personal award given for the first time to a departing secretary of defense by senior NCOs. He resumed his teaching at Stanford, full-time and under an endowed chair, the Michael and Barbara Berberian Chair. He and Ash Carter, the latter at Harvard, resumed their collaboration, co-authoring a book dramatizing their ideas on foreign policy in the nuclear era, Preventive Defense, together with a joint study program. He began devoting most of his time to a worldwide series of Track 2 diplomatic missions on national security and the nuclear issue.

This chapter describes the deteriorating relationship with Russia in the years after Perry had left the Pentagon. Social/political turmoil in Russia is pivotal, fostering nostalgia for "the good old days." Perry recounts how the transfer of power to Vladimir Putin increased hostility. The US European BMD system heightened mistrust. Perry presents this chapter as a parable of how fast relations can turn sour between great nations when they operate in opposition to one another. Perry characterizes the downturn as one of the most unfortunate blows to cooperative resolution of the nuclear issue. He categorizes the issue as potentially a most dangerous one in the nuclear era. His major Track 2 emphasis lies in improving the impasse.

This chapter highlights one of the most profound insights into preventing use of nuclear weapons, namely, MAED (Mutual Assured Economic Destruction), which in our post Cold War time of a global economy with especially critical regional economic relationships, has become an effective deterrent. Perry describes and analyzes such initiatives as cultivating major economic trade between such regional foes as India and Pakistan and China and Taiwan, creating a deterrence of military conflict in the interests of mutual prosperity. The chapter includes description of the tension between China, Taiwan, and Japan over unpopulated islands located between Taiwan and Okinawa, with insistent claims and counter claims. Likewise, Perry recounts concerns over another Mumbai-like terrorist attack by a Pakistani terror group against India. MAED is discussed as deterring the arising of a dangerous military conflict between nuclear powers.

This chapter describes complex diplomacy surrounding the North Korean nuclear crisis commencing in 1998, notably their threatening missile developments. Although the Agreed Framework Perry established with North Korea had earlier resolved nuclear issues, new risks appeared since he had left the Pentagon. President Clinton asks Perry to lead a North Korean Policy Review, Perry assembles a superb team to include Ash Carter, and takes a collaborative approach by inviting major Japanese and South Korean officials to join in the diplomacy. Perry chronicles how time overtook his effort, a most promising one, with the end of the Clinton Administration. Believed excellent during the work of the North Korean Policy Review, prospects of success diminished under the Bush Administration until now we face an angry and defiant North Korea expanding its nuclear weapons capability. In Perry's words, it is "perhaps the most unsuccessful exercise of diplomacy in our country's history."

Asa member of the Iraq Study Group (ISG), Perry cites the invasion as a prime example of how not to succeed in controlling the spread of nuclear weapons. The chapter describes the twin failures of assuming Iraq (a) possessed weapons of mass destruction (WMD) and (b) was supporting Al Queda to mount further terror strikes. The chapter recounts how the ISG's recommendations provided a basis for the Bush Administration to change the losing strategy in Iraq by adopting the Petraeus strategy stressing support of Sunnis in Anwar Province. However, Perry points out that an overall turn for the better in Iraq, notably a more inclusive politics, remains but a remote possibility, most probably beyond accomplishing in the short run.

This chapter describes the advocacy of an international program whose sequence of steps could lead to a world without nuclear weapons. The chapter chronicles how veteran national security experts George Schultz, Sam Nunn, Henry Kissinger, and Perry joined forces to raise international awareness of the dynamics in which the US and Russia might take the lead in reducing the nuclear threat. Measures include providing more time for leaders to work through possible crises, accelerate nuclear reduction through arms control agreements, and establish global systems to secure and control fissionable material. The chapter recounts how op-eds by the four experts attracted great attention, including in the Obama White House, and led to promising further participation by other advocates for a safer world. The chapter concludes with a call to further action to prevent a decline in interest and a return to passivity on this crucial issue.

This chapter describes the basis for hope that removing nuclear weapons from the world becomes an idea whose time has come. The chapter indicates that there are more than a few obstacles that may make that possibility unlikely, the result eventually becoming dire. But Perry reviews the considerable progress that has been made during the nuclear era from the 1940s to the present: significant reductions in weapon inventories, greater awareness of the common good in reducing the threat, serious and growing efforts to secure fissionable material from falling into the hands of terror groups. In the final analysis, Perry points out that much comes down to the faith in humans, in the words of William Faulkner, that "man will not merely endure: he will prevail."