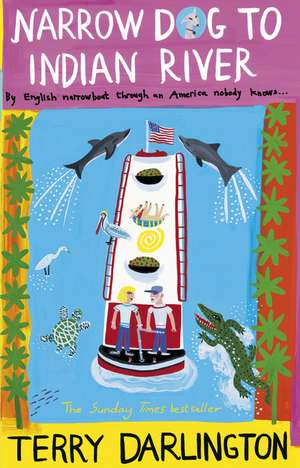

Narrow Dog to Indian River

Autor Terry Darlingtonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 8 apr 2009

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 69.45 lei 24-30 zile | +25.36 lei 4-10 zile |

| Transworld Publishers Ltd – 8 apr 2009 | 69.45 lei 24-30 zile | +25.36 lei 4-10 zile |

| DELTA – 31 mar 2009 | 112.23 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 69.45 lei

Preț vechi: 82.68 lei

-16% Nou

Puncte Express: 104

Preț estimativ în valută:

13.29€ • 13.82$ • 10.97£

13.29€ • 13.82$ • 10.97£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 27 martie-02 aprilie

Livrare express 07-13 martie pentru 35.35 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780553818161

ISBN-10: 0553818163

Pagini: 432

Ilustrații: Line drawings

Dimensiuni: 126 x 198 x 40 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: Transworld Publishers Ltd

Locul publicării:United Kingdom

ISBN-10: 0553818163

Pagini: 432

Ilustrații: Line drawings

Dimensiuni: 126 x 198 x 40 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: Transworld Publishers Ltd

Locul publicării:United Kingdom

Descriere

Takes readers on a dangerous, surprising and entertaining journey as a thousand miles of the little-known South-East Seaboard unfold at six miles an hour - the golden marshes of the Carolinas, the incomparable cities of Charleston and Savannah, and the lost arcadias of Georgia and Florida.

Notă biografică

Terry Darlington was raised in Wales. He likes boating but doesn't know much about it. Monica Darlington has run thirty marathons and leaps tall buildings in a single bound. She likes boating. Brynula Great Expectations (Jim) is sprung from a long line of dogs with ridiculous names. Cowardly, thieving, and disrespectful, he hates boating.

Extras

Thier gods are not our gods

THE TROUBLE WITH YOU IS YOU ARE OBSESSED with the USA, said Monica. The GIs gave you too much gum in the war and you read too many comics and saw too many films-too much Captain Marvel, too much Tarzan, too much Terry and the Pirates, too much Alan Ladd. But America will crush you like it always has. Remember after the New York Marathon, when that gay fireman went off with you over his shoulder? If I hadn't come along you would be Tits Magee now, the Limey Queen of Greenwich Village. I was in a bit of a state, I said. He was trying to help-he was very nice.

What about when you opened an office on Madison Avenue and lost us a fortune twice? Now you want to sail down the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway. It is eleven hundred miles long. There are sea crossings bigger than the English Channel. There are flies. There are alligators. There are winds that blow at two hundred miles an hour. Ten thousand people drowned in Galveston and look what happened to New Orleans. And you want to sail down it in a canal boat six feet ten inches wide. There's no such thing as a wind of two hundred miles an hour, I said-the air would catch fire. And Galveston and New Orleans are somewhere else-they are on the Gulf of Mexico.

But that's where you want us to go, isn't it? A narrowboat on the Gulf of Mexico, and you have conquered the US or died in the attempt. And Jim has to die with us. You and me are seventy; we've had our lives, but Jim's only five. He knows you are going boating again-the way he looks at us and shivers. This isn't the Trent and Mersey Canal, it's not the Thames at Henley, it's not the Rhône-this is a bloody wilderness, halfway round the world. You could stay at home, I said.

You would never come back. Your bloated corpse will be found in some deserted bayou, half eaten by alligators, with three times the permitted alcohol level.

We'll go over and do a recce-check out both ends of the journey:Virginia and Florida. Trust me-I would never do anything to upset my Mon. Slightest problem, we'll stay at home. How about rednecks and bikers, are they a slightest problem? How about gun nuts and gangsters? How about snakes and poison ivy and rip tides? How about hip-hop and preachers on the radio for a year? How about you have always buggered it up in America and now you are going to do it again? I knew there was something funny about you from the start- just because you went to Oxford and liked poetry I thought you were OK. In fact you are a bloody lunatic, and I don't know what I ever saw in you.

It was my pilgrim soul, I said, and my commanding presence, and my wild, careless laugh.

I could have married that Frenchman, said Monica. He looked like Yves Montand.

HALFWAY UP THE EAST COAST OF THE USA, Chesapeake Bay reaches a hundred miles towards Washington. At the mouth of Chesapeake Bay you turn south into the Elizabeth River. On the left is Norfolk, and on the right, Portsmouth. From our hotel room over Norfolk we looked down the river, a quarter of a mile wide. The Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway begins here, and follows the river for seven miles, and then sets out across the Great Dismal Swamp. We didn't know much about the Great Dismal Swamp, but we were not sure we liked the sound of it.

Over the river a US Navy aircraft carrier, and nearer to us a ferry crawling between the two cities; wood and rails, its false paddle-wheel turning. The sun came up quicker than in Stone, and the river went to flame then deepest blue.

There were seventeen breakfasts in the hotel, and lots of African-American waitresses who said y'all all the time. We knew most of the breakfasts, except for the biscuits and gravy. The biscuits were scones, and the gravy was a salty white sauce. There were funny little sausages and hills of crispy bacon. So that's what happened, I said, to the crispy bacon we used to have before the war.

If you stood at the buffet an African-American gentleman would cook you a waffle, and you could have sauce made from fake cherries, or syrup made from fake maples. We'll get fat, said Monica. And we are already fat after sailing through France.

No doubt, I said, but what can you do? The North American continent is blessed with the riches of nature, and covered thinly with maple syrup.

DAVE, THE OPERATIONS MANAGER OF ATLANTIC Containers at Portsmouth Marine Terminal, was a nice man with a beard. So that's a narrowboat, he said, looking at a photograph of the Phyllis May. Never seen one before-my God she's thin.

Most of the canal boats in England are like this, I said-the locks on the main system are only seven feet wide. The original barges were seventy feet long, ten feet longer than the Phyllis May. They were pulled by horses. The boating families lived in the little cabin at the back. It was a culture of its own and it died out when the railways and lorries took over. Then in the nineteen fifties people started making narrowboats out of steel as leisure boats.

How much does she weigh?

Seventeen tons. Ten-millimetre flat bottom: paving stones for ballast. Draws two feet-on a wet day you can sail her up Stafford High Street.

What's she like to steer?

You stand on that counter at the stern, and hold the tiller behind your back. She has no bow thrusters but I can do most of what I want if there are no big waves or winds or currents.

There are big waves and winds and currents on the Intracoastal, said Dave.

He took us round the terminal. Containers in piles, and machines a hundred feet high with two legs that pick up the containers between their knees and roar about and put them down somewhere else. Yachts on trolleys, and lorries and helicopters and tanks, waiting for the fifty-thousand-ton roll-on roll-off container ship that will carry them off around the world.

This is your crane, said Dave-the little one. We call him Clyde. He's only two hundred feet high. I guess you will want to be on your boat when we drop her in. Yes, said Monica, he will, and Jim and I will stay on the wharf.

I tried to take a photo of Clyde but I couldn't get far enough away.

Dave introduced us to the ladies in the Portsmouth Marine Terminal office. We can't wait to meet Jim, said Nice Amy. We have eleven dogs between five of us. Tell Jim that we will have several bags of pork skins waiting when y'all arrive-are they the same as pork scratchings?

In June, I said, Jim will give us an opinion.

DOWN THE INTRACOASTAL WATERWAY AT thirty thousand feet. A thread of silver across the Great Dismal Swamp, which looked like the weather map on the telly when it's raining. Then sunlight on Albemarle Sound, and on Pamlico Sound, both wider than the English Channel. Along North Carolina the chalk line of Atlantic surf, and just inland the silver thread welling into lagoons and swamps and meanders. In South Carolina, past Charleston, and then through Georgia, the coastline is a madman's jigsaw, and it doesn't get much better in Florida. Now Lake Okeechobee is on our right, misty blue to the horizon, and the Everglades draining in endless patterns to the south.

We turn along Alligator Alley, the motorway across the peninsula, hold to the fast lane, and glide into the long slow afternoon of western Florida.

THE TROUBLE WITH YOU IS YOU ARE OBSESSED with the USA, said Monica. The GIs gave you too much gum in the war and you read too many comics and saw too many films-too much Captain Marvel, too much Tarzan, too much Terry and the Pirates, too much Alan Ladd. But America will crush you like it always has. Remember after the New York Marathon, when that gay fireman went off with you over his shoulder? If I hadn't come along you would be Tits Magee now, the Limey Queen of Greenwich Village. I was in a bit of a state, I said. He was trying to help-he was very nice.

What about when you opened an office on Madison Avenue and lost us a fortune twice? Now you want to sail down the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway. It is eleven hundred miles long. There are sea crossings bigger than the English Channel. There are flies. There are alligators. There are winds that blow at two hundred miles an hour. Ten thousand people drowned in Galveston and look what happened to New Orleans. And you want to sail down it in a canal boat six feet ten inches wide. There's no such thing as a wind of two hundred miles an hour, I said-the air would catch fire. And Galveston and New Orleans are somewhere else-they are on the Gulf of Mexico.

But that's where you want us to go, isn't it? A narrowboat on the Gulf of Mexico, and you have conquered the US or died in the attempt. And Jim has to die with us. You and me are seventy; we've had our lives, but Jim's only five. He knows you are going boating again-the way he looks at us and shivers. This isn't the Trent and Mersey Canal, it's not the Thames at Henley, it's not the Rhône-this is a bloody wilderness, halfway round the world. You could stay at home, I said.

You would never come back. Your bloated corpse will be found in some deserted bayou, half eaten by alligators, with three times the permitted alcohol level.

We'll go over and do a recce-check out both ends of the journey:Virginia and Florida. Trust me-I would never do anything to upset my Mon. Slightest problem, we'll stay at home. How about rednecks and bikers, are they a slightest problem? How about gun nuts and gangsters? How about snakes and poison ivy and rip tides? How about hip-hop and preachers on the radio for a year? How about you have always buggered it up in America and now you are going to do it again? I knew there was something funny about you from the start- just because you went to Oxford and liked poetry I thought you were OK. In fact you are a bloody lunatic, and I don't know what I ever saw in you.

It was my pilgrim soul, I said, and my commanding presence, and my wild, careless laugh.

I could have married that Frenchman, said Monica. He looked like Yves Montand.

HALFWAY UP THE EAST COAST OF THE USA, Chesapeake Bay reaches a hundred miles towards Washington. At the mouth of Chesapeake Bay you turn south into the Elizabeth River. On the left is Norfolk, and on the right, Portsmouth. From our hotel room over Norfolk we looked down the river, a quarter of a mile wide. The Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway begins here, and follows the river for seven miles, and then sets out across the Great Dismal Swamp. We didn't know much about the Great Dismal Swamp, but we were not sure we liked the sound of it.

Over the river a US Navy aircraft carrier, and nearer to us a ferry crawling between the two cities; wood and rails, its false paddle-wheel turning. The sun came up quicker than in Stone, and the river went to flame then deepest blue.

There were seventeen breakfasts in the hotel, and lots of African-American waitresses who said y'all all the time. We knew most of the breakfasts, except for the biscuits and gravy. The biscuits were scones, and the gravy was a salty white sauce. There were funny little sausages and hills of crispy bacon. So that's what happened, I said, to the crispy bacon we used to have before the war.

If you stood at the buffet an African-American gentleman would cook you a waffle, and you could have sauce made from fake cherries, or syrup made from fake maples. We'll get fat, said Monica. And we are already fat after sailing through France.

No doubt, I said, but what can you do? The North American continent is blessed with the riches of nature, and covered thinly with maple syrup.

DAVE, THE OPERATIONS MANAGER OF ATLANTIC Containers at Portsmouth Marine Terminal, was a nice man with a beard. So that's a narrowboat, he said, looking at a photograph of the Phyllis May. Never seen one before-my God she's thin.

Most of the canal boats in England are like this, I said-the locks on the main system are only seven feet wide. The original barges were seventy feet long, ten feet longer than the Phyllis May. They were pulled by horses. The boating families lived in the little cabin at the back. It was a culture of its own and it died out when the railways and lorries took over. Then in the nineteen fifties people started making narrowboats out of steel as leisure boats.

How much does she weigh?

Seventeen tons. Ten-millimetre flat bottom: paving stones for ballast. Draws two feet-on a wet day you can sail her up Stafford High Street.

What's she like to steer?

You stand on that counter at the stern, and hold the tiller behind your back. She has no bow thrusters but I can do most of what I want if there are no big waves or winds or currents.

There are big waves and winds and currents on the Intracoastal, said Dave.

He took us round the terminal. Containers in piles, and machines a hundred feet high with two legs that pick up the containers between their knees and roar about and put them down somewhere else. Yachts on trolleys, and lorries and helicopters and tanks, waiting for the fifty-thousand-ton roll-on roll-off container ship that will carry them off around the world.

This is your crane, said Dave-the little one. We call him Clyde. He's only two hundred feet high. I guess you will want to be on your boat when we drop her in. Yes, said Monica, he will, and Jim and I will stay on the wharf.

I tried to take a photo of Clyde but I couldn't get far enough away.

Dave introduced us to the ladies in the Portsmouth Marine Terminal office. We can't wait to meet Jim, said Nice Amy. We have eleven dogs between five of us. Tell Jim that we will have several bags of pork skins waiting when y'all arrive-are they the same as pork scratchings?

In June, I said, Jim will give us an opinion.

DOWN THE INTRACOASTAL WATERWAY AT thirty thousand feet. A thread of silver across the Great Dismal Swamp, which looked like the weather map on the telly when it's raining. Then sunlight on Albemarle Sound, and on Pamlico Sound, both wider than the English Channel. Along North Carolina the chalk line of Atlantic surf, and just inland the silver thread welling into lagoons and swamps and meanders. In South Carolina, past Charleston, and then through Georgia, the coastline is a madman's jigsaw, and it doesn't get much better in Florida. Now Lake Okeechobee is on our right, misty blue to the horizon, and the Everglades draining in endless patterns to the south.

We turn along Alligator Alley, the motorway across the peninsula, hold to the fast lane, and glide into the long slow afternoon of western Florida.