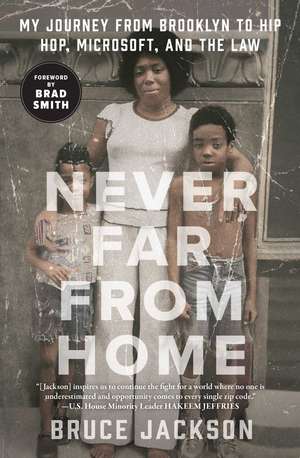

Never Far from Home: My Journey from Brooklyn to Hip Hop, Microsoft, and the Law

Autor Bruce Jackson Cuvânt înainte de Brad Smithen Limba Engleză Paperback – 13 mar 2024

As an accomplished Microsoft executive, Bruce Jackson handles billions of dollars of commerce as its associate general counsel while he plays a crucial role in the company’s corporate diversity efforts. But few of his colleagues can understand the weight he carries with him to the office each day. He kept his past hidden from sight as he ascended the corporate ladder but shares it in full for the first time here.

Born in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, Jackson moved to Manhattan’s Amsterdam housing projects as a child, where he had already been falsely accused and arrested for robbery by the age of ten. At the age of fifteen, he witnessed the homicide of his close friend. Taken in by the criminal justice system, seduced by a burgeoning drug trade, and burdened by a fractured, impoverished home life, Jackson stood on the edge of failure. But he was saved by an offer. That offer set him on a better path, off the streets and eventually on the way to Georgetown Law, but not without hard knocks along the way.

From public housing to working for Microsoft’s president, Brad Smith, and its founder, Bill Gates, to advising some of the biggest stars in music, Bruce Jackson’s Never Far from Home is “an important story, extremely well told, that should serve as a lesson on how we got here and where we need to go” (Fred D. Gray, activist and civil rights attorney).

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (1) | 69.42 lei 3-5 săpt. | +8.41 lei 7-13 zile |

| ATRIA – 13 mar 2024 | 69.42 lei 3-5 săpt. | +8.41 lei 7-13 zile |

| Hardback (1) | 101.38 lei 28-40 zile | |

| ATRIA – 30 mar 2023 | 101.38 lei 28-40 zile |

Preț: 69.42 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 104

Preț estimativ în valută:

13.28€ • 13.87$ • 10.99£

13.28€ • 13.87$ • 10.99£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 14-28 martie

Livrare express 28 februarie-06 martie pentru 18.40 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781982191160

ISBN-10: 1982191163

Pagini: 272

Dimensiuni: 140 x 213 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: ATRIA

Colecția Atria Books

ISBN-10: 1982191163

Pagini: 272

Dimensiuni: 140 x 213 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: ATRIA

Colecția Atria Books

Notă biografică

Bruce Jackson is an associate general counsel at Microsoft and managing director for strategic partnerships out of the office of the president at Microsoft. Born in Brooklyn, he studied law at Georgetown University and spent a decade working in entertainment law with some of the top music talent in the country. Since then, he has received Microsoft’s diversity award, participated in Microsoft’s law and corporate affairs’ diversity efforts, helped launch Microsoft’s Elevate American Veterans Initiative, and worked to develop its diverse recruitment pipeline. Never Far from Home is his first book.

Extras

Prologue: New York, 2010Prologue NEW YORK, 2010

The Amsterdam Houses never change. The sprawling housing project comes into view as I make the familiar left turn from Eleventh Avenue onto Sixty-First Street and climb uphill from Manhattan’s west side. The Houses are a city within a city: nine acres, more than a thousand residents, and countless stories that never see the light of day. The mass of brick towers feels as foreboding as ever—bad enough for me when I get pulled back for an extended residency every few years, but worse still for my mother, who remains as stuck to this place as the memories of my youth on the edge. This time, I’ve been brought back by the twin traumas of an imploding marriage and a house fire that has rendered uninhabitable my home in Mount Vernon, New York.

But this place is home, always will be. To me and countless friends and relatives here and gone, too many now lost to drugs and violence and crime. Yesterday, a Sunday, I broke bread with some of the folks in this neighborhood and joined with them in prayer at Sunday service. Today, my team closed a hundred-million-dollar deal for Microsoft, where I’ve worked for more than a decade. We held a party in the office to mark the win. Then I met a friend and drove to the grocery store to pick up a batch of crab legs and some beers—for a celebration party with family and friends.

Some people—and this is especially true of those who grew up poor—like to dig at their roots until they give way completely, and there is nothing to draw them back. Makes it easier to shape-shift into something else; to blend in at corporate functions or black-tie charity events.

I want to help these people. But don’t get the wrong idea. I was never one of them.

Not me, but I get it. If you’re uncomfortable with who and what you were, you want to pretend it never happened. But as far as I’m concerned, everything I’ve accomplished grew from the roots of the city and projects and distressed neighborhoods that raised me. The Houses are no less a part of me than the blood that flows through my veins. Hell, I’m proud of it. But I also know it could have turned out like it did for many of my friends: dead or incarcerated. Reality has a way of shaking me awake whenever I’m tempted to forget about that fact.

Right on cue: Blue and red lights dance kaleidoscopically in the rearview mirror, revealing the unmistakable outline of an NYPD cruiser. Then two quick burps of a siren, as if I hadn’t already gotten the message. I pull my gray BMW X5 to the curb, cut the engine, and wait. Hands on the wheel. Ten and two. Eyes ahead. I am an attorney, so I know my rights. I am also a Black man in America, so I know the drill.

“Relax,” I say to my passenger, an old friend, to my right. “It’ll be okay.”

Two officers, both fair-skinned, approach the vehicle. I roll down the window, try to remain calm. The officers are cordial but firm.

“Been following you since the bottom of the hill,” one of them explains.

They say something is wrong with the taillight.

This is not true, but it falls under the vast umbrella of “probable cause.” A taillight that appears to be flickering is as useful a tool to law enforcement, when so inclined, as blacked-out windows or a rumbling muffler. It is an excuse to detain, to intrude and violate. And so the dance begins. I turn over my license and registration. The officers retreat to their cruiser. Five minutes pass… ten… fifteen. By the time they return and declare flatly that “something” showed up on my license, and that they need to wait for their sergeant to report back, my friend skips from agitation straight to anger.

“This is bullshit!”

She may be right, but the outburst—continuous, peppered with expletives and accusations of racism—is not helping matters.

“You’re just stopping him because he’s a Black man.”

“Ma’am, you keep running your mouth,” one of the cops says, “I’m going to arrest you.”

There is a standoff—the cop looks at me, with an unspoken Get your friend under control—before he walks away again. A crowd begins to gather on this pleasant spring night, ready for an unexpected show after dinner. Suddenly a backup patrol car hits the scene, and there are now four cops investigating an allegedly busted taillight. My hopes of a simple ticket and a talking-to are fading fast.

“Look,” I say to my friend, “I think they’re going to take me downtown. Maybe it’s best if you leave.”

“Leave?”

“Yeah. Take my keys and my car. Go home. I’ll stay with the cops. Let’s not make this any worse than it is. I’ll be okay.”

The officer strolls back over to the driver’s side window. After a brief discussion, my friend is allowed to leave, right before I am handcuffed and placed in the back seat of a cruiser. More will be revealed in due time, they promise, but for now, There is a problem with your license is all I’ll get.

First stop: Twentieth Precinct, West Eighty-Second Street. I am placed in a holding area with four other men and then moved to a cell all my own.

“Want a newspaper?” one officer asks.

“Sure. Thanks.”

Time passes. Time to think about the fact that it’s been nearly forty years since the last time I found myself in this situation, detained by law enforcement. So much has changed in my life, and apparently, so little. The officer returns. There are two women outside, he explains, and they aren’t happy. He tells me their names—Adrienne and Diane. One, my friend and passenger from earlier, the other, my sister. They arrived together at the Twentieth Precinct to raise hell.

“Do me a favor,” I say. “Tell them I’m sleeping.”

He laughs. “Sleeping?”

“Yeah, if they think I’m comfortable and not bothered by this, that will put them at ease.”

He shrugs, leaves, returns a while later. “They’re gone. Guess you were right.”

It is close to midnight when my attorney, Paul Martin, shows up. By this time, I have been informed of the charges—driving with a suspended license. Apparently my brother had picked up a parking ticket while driving my car and had failed to pay the fine. This transgression was news to me, but it was my responsibility, since the ticket was attached to a vehicle registered in my name.

Fair enough, but the truth is that no one—or almost no one—spends any time at all behind bars for nonpayment of a parking ticket or even a suspended license. The US judicial system is already choked to the point of immobility without tossing parking tickets into the blender. Typically, this kind of infraction merits a desk ticket and a future date with the state on the court docket. But, of course, justice is not blind, and here I am, a middle-aged man with a career on the rise and no criminal record, suddenly thrown into the system.

“Prints didn’t come back yet,” Paul says glumly.

I nod, knowing exactly what this means. If fingerprints don’t clear the system by midnight, you’re spending the night in jail.

“Hang in there,” he says. “I’ll see you tomorrow.”

Moments later I am in handcuffs again, and leg irons, one of four men chained together, shuffling out a back door. They load us into a van and drive us uptown, to 126th Street, home of the Twenty-Sixth, a larger and more heavily staffed precinct. More cops. More cells. More criminals. We pass through metal door after metal door, the deafening CLANG of each a reminder of the fading light and intensifying odor as we fall deeper into the system.

I can feel my heart race. This is not exactly Rikers Island, but make no mistake—the tone and tenor of this facility shares little with my time reading a newspaper at the comparatively genteel Twentieth Precinct. The sense of dread is palpable. The four of us are divided and placed in different cells, all within view of one another. There is one other occupant in mine, a man who appears to be in his early thirties, wearing a ragged T-shirt and jeans. He is sprawled out on the cell’s only bench, snoring away. I stand at the door, leaning against the bars, wondering how long I’ll be here, how I got here. Until this night, I’ve never spent a minute behind bars, but I know enough about the streets and jailhouse protocol to know that if I stand here all night, peering out of the cell like a puppy in a kennel, a couple bad things will happen. One, I’ll be exhausted. Two, I’ll become a target in the eyes of my cellmate and anyone else who might join us later.

“Yo, man,” I say as I walk to the bench. “Wake up.”

The guy moans, rolls over, looks at me through dead eyes. He says nothing.

“I’m tired, too,” I say. “I can’t stand here all night. You gotta move over and give me some room.”

He nods, sits up, and slides to the end of the bench. Then curls into himself again. I take a seat at the other end and begin my fight with the anxiety of incarceration. My chest is tight, my throat dry. Suddenly I am nearly overcome with the urge to scream, to let everyone within earshot know that I DON’T BELONG HERE! My hands are clammy. The room is spinning.

Get a grip, I tell myself. It isn’t that bad, you’ll be out in the morning. But the lack of control is terrifying: the sense that I am buried deep within this maze of broken dreams and violence and no one gives a shit.

“Sandwich?”

There is an officer at the gate, passing out food, or something like it, anyway. Flattened slices of white bread wrapped in cellophane.

“No, thanks.”

He holds out a bottled water. I consider it briefly. I’m thirsty, scared. But there is a single, open toilet in a corner of the cell, and anything that needs to leave my body will be doing so for an audience.

“Nah.”

He shrugs, walks away.

I close my eyes and withdraw into a fantasy world: a meditative trance, of sorts. Summoning up a long-lost part of my past, from adolescent flirtations with the theater, I slip into character. In this scenario, I am not a criminal. I am a correspondent, working undercover; an intrepid investigative journalist rooting out inequities and racial injustice by placing himself on the front lines of the war. I tell myself that I am merely a visitor to this universe, not a resident. I am here to observe and report. I am here to learn.

And then go home.

It’s all nonsense, but in a weird way it helps. After a while, my pulse slackens. My skin dries. I can breathe again. An hour passes, maybe two.

We are cuffed and chained together again, only this time there are eight of us, led out of the basement jail and into a waiting van. Accompanied fore and aft by NYPD patrol cars, we rumble down the West Side Highway beneath the cover of night, the city eerily still and quiet. There is a small window in the back of the vehicle, and through it I see the city lights flickering off the Hudson, splashing fingers of yellow and orange across the black water. A few of the guys around me manage to fall asleep, even as the van bobs and weaves along the rutted highway. We are on our way to Central Booking, stop number three on the night, and I can’t help but think about the fact that absolutely no one who cares about me has any idea where I am at this moment. But I’m lucky: at least I know they’re out there somewhere, friends and family who love me and who would be horrified to see me like this. I wonder if the same can be said of my fellow travelers.

Central Booking, 100 Centre Street, is a sprawling short-term lockup and courthouse in Lower Manhattan that serves as a way station for hundreds of inmates as they are fed into one of the penal system’s many tributaries. If you get to Central Booking, the thinking goes, you probably did… something. The holding cells are bigger, nastier, louder. The guards and officers are tougher, more cynical.

I am tossed into a cage with roughly a dozen other men, most of whom appear to be half my years (forty-eight). But it’s easier this time, even with a crowd. It’s the middle of the night, but I walk over, tap one of the kids on the back, and tell him to make room. He grunts, moves down. I take a seat.

“The fuck you doin’ here, old man?” one of them says to me.

“I ain’t that old.”

He laughs. The conversation ends. Everyone in jail is innocent, but I see no reason to explain myself. It’s not going to help my credibility, or enhance my safety, to tell anyone that I’ve been arrested for failing to pay a traffic ticket. Better to let them assume the worst.

Time passes. More food and water are offered and rejected. The sun rises, although I can’t see it. Attorneys begin showing up, court-appointed mostly. They speak to clients, accompany them into the courtroom. It goes on like this for hours, a steady march of the accused and the arraigned. Some post bail and leave. Some see their cases dismissed. Quite a few remain on site or are shipped out to serve bids elsewhere or to wait for resolution of more complicated matters. My attorney, Paul, arrives midmorning. He’s calm, reassuring.

“I’ve already spoken to the DA,” he says. “They’re going to dismiss the charges. You just have to pay the ticket, and a fine, and it all gets wiped away.”

“That’s it?”

“Well, you still have to go in front of the judge, acknowledge culpability—”

“It wasn’t my ticket. I didn’t even know about it.”

He sighs. “Come on, Bruce. Doesn’t matter.”

“Uh-huh.”

Soon, it’s all over. I am one of a hundred or more people who will stand in front of the judge, a fleeting and forgotten face. A name on an impossibly long ledger. Outside, Paul and I shake hands and go our separate ways. He offers me a ride uptown, but I decline. I need some time alone to clear my head.

I walk across the street and grab a Big Mac at a McDonald’s on Broadway, polish it off while walking through SoHo. Eventually, I hop on the subway heading north. It has never felt better, the rocking of the car, the clacking of the wheels against the rails. With the exception of college, law school, and a brief, uncomfortable stint in the Pacific Northwest, I’ve lived in and around New York City my entire life. Even on the bad days, it’s home.

I exit at Lincoln Center, the stop nearest the Amsterdam Houses. By now it’s almost noon. Still time to get into work and make something of the day. It’s not until I’m standing in the shower, trying to wash away the stench of eighteen hours in limbo, that the anger and anxiety rise up within me. I feel it all again—the hopelessness. The vile conditions. The stench of urine, of vomit, of nicotine, of sweat. I gag, choke it back.

A few minutes later I am neatly dressed and walking out the front door of one of Manhattan’s largest housing projects, briefcase in hand, on my way to Microsoft Corporation’s New York headquarters on Sixth Avenue. I’ve thought about this juxtaposition more than a few times since moving back home—the distance from here to there, physically and metaphorically—but there is a new poignancy to it today. As I rise through the glistening complex on an elevator to my sixth-floor office, I am nearly broken by the weight of a secret life, of the burden that most of my colleagues cannot possibly understand. Politeness rules. Pleasantries are exchanged, small talk is made. I am overwhelmed by the urge to tell everyone what happened, to share the gory details of a life they can’t imagine.

“This is what can happen,” I want to say, “if you are a person of color.” This is what will happen if we aren’t all vigilant, aware, persistent. Things have changed, mostly for the better. I know that. When I started at Microsoft a decade earlier, I was the third Black person ever hired in the company’s legal department. With diversity and inclusion high on the company agenda, those numbers have improved, and I’ve done my best to help the cause. But up here, in the ivory tower, it’s easy to forget the truth: that when I leave this office, I am not a Microsoft executive.

I want to tell them where I spent the night. I want to explain exactly how my reality differs from theirs when I leave this office. But I don’t. I put my head down and go to work, crunching numbers, reviewing contracts, vetting deals. Someday, maybe I’ll tell them what happened.

Someday.

The Amsterdam Houses never change. The sprawling housing project comes into view as I make the familiar left turn from Eleventh Avenue onto Sixty-First Street and climb uphill from Manhattan’s west side. The Houses are a city within a city: nine acres, more than a thousand residents, and countless stories that never see the light of day. The mass of brick towers feels as foreboding as ever—bad enough for me when I get pulled back for an extended residency every few years, but worse still for my mother, who remains as stuck to this place as the memories of my youth on the edge. This time, I’ve been brought back by the twin traumas of an imploding marriage and a house fire that has rendered uninhabitable my home in Mount Vernon, New York.

But this place is home, always will be. To me and countless friends and relatives here and gone, too many now lost to drugs and violence and crime. Yesterday, a Sunday, I broke bread with some of the folks in this neighborhood and joined with them in prayer at Sunday service. Today, my team closed a hundred-million-dollar deal for Microsoft, where I’ve worked for more than a decade. We held a party in the office to mark the win. Then I met a friend and drove to the grocery store to pick up a batch of crab legs and some beers—for a celebration party with family and friends.

Some people—and this is especially true of those who grew up poor—like to dig at their roots until they give way completely, and there is nothing to draw them back. Makes it easier to shape-shift into something else; to blend in at corporate functions or black-tie charity events.

I want to help these people. But don’t get the wrong idea. I was never one of them.

Not me, but I get it. If you’re uncomfortable with who and what you were, you want to pretend it never happened. But as far as I’m concerned, everything I’ve accomplished grew from the roots of the city and projects and distressed neighborhoods that raised me. The Houses are no less a part of me than the blood that flows through my veins. Hell, I’m proud of it. But I also know it could have turned out like it did for many of my friends: dead or incarcerated. Reality has a way of shaking me awake whenever I’m tempted to forget about that fact.

Right on cue: Blue and red lights dance kaleidoscopically in the rearview mirror, revealing the unmistakable outline of an NYPD cruiser. Then two quick burps of a siren, as if I hadn’t already gotten the message. I pull my gray BMW X5 to the curb, cut the engine, and wait. Hands on the wheel. Ten and two. Eyes ahead. I am an attorney, so I know my rights. I am also a Black man in America, so I know the drill.

“Relax,” I say to my passenger, an old friend, to my right. “It’ll be okay.”

Two officers, both fair-skinned, approach the vehicle. I roll down the window, try to remain calm. The officers are cordial but firm.

“Been following you since the bottom of the hill,” one of them explains.

They say something is wrong with the taillight.

This is not true, but it falls under the vast umbrella of “probable cause.” A taillight that appears to be flickering is as useful a tool to law enforcement, when so inclined, as blacked-out windows or a rumbling muffler. It is an excuse to detain, to intrude and violate. And so the dance begins. I turn over my license and registration. The officers retreat to their cruiser. Five minutes pass… ten… fifteen. By the time they return and declare flatly that “something” showed up on my license, and that they need to wait for their sergeant to report back, my friend skips from agitation straight to anger.

“This is bullshit!”

She may be right, but the outburst—continuous, peppered with expletives and accusations of racism—is not helping matters.

“You’re just stopping him because he’s a Black man.”

“Ma’am, you keep running your mouth,” one of the cops says, “I’m going to arrest you.”

There is a standoff—the cop looks at me, with an unspoken Get your friend under control—before he walks away again. A crowd begins to gather on this pleasant spring night, ready for an unexpected show after dinner. Suddenly a backup patrol car hits the scene, and there are now four cops investigating an allegedly busted taillight. My hopes of a simple ticket and a talking-to are fading fast.

“Look,” I say to my friend, “I think they’re going to take me downtown. Maybe it’s best if you leave.”

“Leave?”

“Yeah. Take my keys and my car. Go home. I’ll stay with the cops. Let’s not make this any worse than it is. I’ll be okay.”

The officer strolls back over to the driver’s side window. After a brief discussion, my friend is allowed to leave, right before I am handcuffed and placed in the back seat of a cruiser. More will be revealed in due time, they promise, but for now, There is a problem with your license is all I’ll get.

First stop: Twentieth Precinct, West Eighty-Second Street. I am placed in a holding area with four other men and then moved to a cell all my own.

“Want a newspaper?” one officer asks.

“Sure. Thanks.”

Time passes. Time to think about the fact that it’s been nearly forty years since the last time I found myself in this situation, detained by law enforcement. So much has changed in my life, and apparently, so little. The officer returns. There are two women outside, he explains, and they aren’t happy. He tells me their names—Adrienne and Diane. One, my friend and passenger from earlier, the other, my sister. They arrived together at the Twentieth Precinct to raise hell.

“Do me a favor,” I say. “Tell them I’m sleeping.”

He laughs. “Sleeping?”

“Yeah, if they think I’m comfortable and not bothered by this, that will put them at ease.”

He shrugs, leaves, returns a while later. “They’re gone. Guess you were right.”

It is close to midnight when my attorney, Paul Martin, shows up. By this time, I have been informed of the charges—driving with a suspended license. Apparently my brother had picked up a parking ticket while driving my car and had failed to pay the fine. This transgression was news to me, but it was my responsibility, since the ticket was attached to a vehicle registered in my name.

Fair enough, but the truth is that no one—or almost no one—spends any time at all behind bars for nonpayment of a parking ticket or even a suspended license. The US judicial system is already choked to the point of immobility without tossing parking tickets into the blender. Typically, this kind of infraction merits a desk ticket and a future date with the state on the court docket. But, of course, justice is not blind, and here I am, a middle-aged man with a career on the rise and no criminal record, suddenly thrown into the system.

“Prints didn’t come back yet,” Paul says glumly.

I nod, knowing exactly what this means. If fingerprints don’t clear the system by midnight, you’re spending the night in jail.

“Hang in there,” he says. “I’ll see you tomorrow.”

Moments later I am in handcuffs again, and leg irons, one of four men chained together, shuffling out a back door. They load us into a van and drive us uptown, to 126th Street, home of the Twenty-Sixth, a larger and more heavily staffed precinct. More cops. More cells. More criminals. We pass through metal door after metal door, the deafening CLANG of each a reminder of the fading light and intensifying odor as we fall deeper into the system.

I can feel my heart race. This is not exactly Rikers Island, but make no mistake—the tone and tenor of this facility shares little with my time reading a newspaper at the comparatively genteel Twentieth Precinct. The sense of dread is palpable. The four of us are divided and placed in different cells, all within view of one another. There is one other occupant in mine, a man who appears to be in his early thirties, wearing a ragged T-shirt and jeans. He is sprawled out on the cell’s only bench, snoring away. I stand at the door, leaning against the bars, wondering how long I’ll be here, how I got here. Until this night, I’ve never spent a minute behind bars, but I know enough about the streets and jailhouse protocol to know that if I stand here all night, peering out of the cell like a puppy in a kennel, a couple bad things will happen. One, I’ll be exhausted. Two, I’ll become a target in the eyes of my cellmate and anyone else who might join us later.

“Yo, man,” I say as I walk to the bench. “Wake up.”

The guy moans, rolls over, looks at me through dead eyes. He says nothing.

“I’m tired, too,” I say. “I can’t stand here all night. You gotta move over and give me some room.”

He nods, sits up, and slides to the end of the bench. Then curls into himself again. I take a seat at the other end and begin my fight with the anxiety of incarceration. My chest is tight, my throat dry. Suddenly I am nearly overcome with the urge to scream, to let everyone within earshot know that I DON’T BELONG HERE! My hands are clammy. The room is spinning.

Get a grip, I tell myself. It isn’t that bad, you’ll be out in the morning. But the lack of control is terrifying: the sense that I am buried deep within this maze of broken dreams and violence and no one gives a shit.

“Sandwich?”

There is an officer at the gate, passing out food, or something like it, anyway. Flattened slices of white bread wrapped in cellophane.

“No, thanks.”

He holds out a bottled water. I consider it briefly. I’m thirsty, scared. But there is a single, open toilet in a corner of the cell, and anything that needs to leave my body will be doing so for an audience.

“Nah.”

He shrugs, walks away.

I close my eyes and withdraw into a fantasy world: a meditative trance, of sorts. Summoning up a long-lost part of my past, from adolescent flirtations with the theater, I slip into character. In this scenario, I am not a criminal. I am a correspondent, working undercover; an intrepid investigative journalist rooting out inequities and racial injustice by placing himself on the front lines of the war. I tell myself that I am merely a visitor to this universe, not a resident. I am here to observe and report. I am here to learn.

And then go home.

It’s all nonsense, but in a weird way it helps. After a while, my pulse slackens. My skin dries. I can breathe again. An hour passes, maybe two.

We are cuffed and chained together again, only this time there are eight of us, led out of the basement jail and into a waiting van. Accompanied fore and aft by NYPD patrol cars, we rumble down the West Side Highway beneath the cover of night, the city eerily still and quiet. There is a small window in the back of the vehicle, and through it I see the city lights flickering off the Hudson, splashing fingers of yellow and orange across the black water. A few of the guys around me manage to fall asleep, even as the van bobs and weaves along the rutted highway. We are on our way to Central Booking, stop number three on the night, and I can’t help but think about the fact that absolutely no one who cares about me has any idea where I am at this moment. But I’m lucky: at least I know they’re out there somewhere, friends and family who love me and who would be horrified to see me like this. I wonder if the same can be said of my fellow travelers.

Central Booking, 100 Centre Street, is a sprawling short-term lockup and courthouse in Lower Manhattan that serves as a way station for hundreds of inmates as they are fed into one of the penal system’s many tributaries. If you get to Central Booking, the thinking goes, you probably did… something. The holding cells are bigger, nastier, louder. The guards and officers are tougher, more cynical.

I am tossed into a cage with roughly a dozen other men, most of whom appear to be half my years (forty-eight). But it’s easier this time, even with a crowd. It’s the middle of the night, but I walk over, tap one of the kids on the back, and tell him to make room. He grunts, moves down. I take a seat.

“The fuck you doin’ here, old man?” one of them says to me.

“I ain’t that old.”

He laughs. The conversation ends. Everyone in jail is innocent, but I see no reason to explain myself. It’s not going to help my credibility, or enhance my safety, to tell anyone that I’ve been arrested for failing to pay a traffic ticket. Better to let them assume the worst.

Time passes. More food and water are offered and rejected. The sun rises, although I can’t see it. Attorneys begin showing up, court-appointed mostly. They speak to clients, accompany them into the courtroom. It goes on like this for hours, a steady march of the accused and the arraigned. Some post bail and leave. Some see their cases dismissed. Quite a few remain on site or are shipped out to serve bids elsewhere or to wait for resolution of more complicated matters. My attorney, Paul, arrives midmorning. He’s calm, reassuring.

“I’ve already spoken to the DA,” he says. “They’re going to dismiss the charges. You just have to pay the ticket, and a fine, and it all gets wiped away.”

“That’s it?”

“Well, you still have to go in front of the judge, acknowledge culpability—”

“It wasn’t my ticket. I didn’t even know about it.”

He sighs. “Come on, Bruce. Doesn’t matter.”

“Uh-huh.”

Soon, it’s all over. I am one of a hundred or more people who will stand in front of the judge, a fleeting and forgotten face. A name on an impossibly long ledger. Outside, Paul and I shake hands and go our separate ways. He offers me a ride uptown, but I decline. I need some time alone to clear my head.

I walk across the street and grab a Big Mac at a McDonald’s on Broadway, polish it off while walking through SoHo. Eventually, I hop on the subway heading north. It has never felt better, the rocking of the car, the clacking of the wheels against the rails. With the exception of college, law school, and a brief, uncomfortable stint in the Pacific Northwest, I’ve lived in and around New York City my entire life. Even on the bad days, it’s home.

I exit at Lincoln Center, the stop nearest the Amsterdam Houses. By now it’s almost noon. Still time to get into work and make something of the day. It’s not until I’m standing in the shower, trying to wash away the stench of eighteen hours in limbo, that the anger and anxiety rise up within me. I feel it all again—the hopelessness. The vile conditions. The stench of urine, of vomit, of nicotine, of sweat. I gag, choke it back.

A few minutes later I am neatly dressed and walking out the front door of one of Manhattan’s largest housing projects, briefcase in hand, on my way to Microsoft Corporation’s New York headquarters on Sixth Avenue. I’ve thought about this juxtaposition more than a few times since moving back home—the distance from here to there, physically and metaphorically—but there is a new poignancy to it today. As I rise through the glistening complex on an elevator to my sixth-floor office, I am nearly broken by the weight of a secret life, of the burden that most of my colleagues cannot possibly understand. Politeness rules. Pleasantries are exchanged, small talk is made. I am overwhelmed by the urge to tell everyone what happened, to share the gory details of a life they can’t imagine.

“This is what can happen,” I want to say, “if you are a person of color.” This is what will happen if we aren’t all vigilant, aware, persistent. Things have changed, mostly for the better. I know that. When I started at Microsoft a decade earlier, I was the third Black person ever hired in the company’s legal department. With diversity and inclusion high on the company agenda, those numbers have improved, and I’ve done my best to help the cause. But up here, in the ivory tower, it’s easy to forget the truth: that when I leave this office, I am not a Microsoft executive.

I want to tell them where I spent the night. I want to explain exactly how my reality differs from theirs when I leave this office. But I don’t. I put my head down and go to work, crunching numbers, reviewing contracts, vetting deals. Someday, maybe I’ll tell them what happened.

Someday.

Recenzii

“Bruce Jackson's portrait of New York is as nuanced as it is hopeful. In grappling with the complexity of his own childhood—from poverty's pernicious effect on his neighbors to early encounters with a flawed criminal justice system—Jackson asks his readers to confront the systemic inequalities that continue to plague communities of color across our nation. Jackson's own story of success, with the support of a loving extended family and key mentors along the way, inspires us to continue the fight for a world where no one is underestimated and opportunity comes to every single zip code.” —U.S. House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries

“A valuable reminder of the invisible hurdles set in front of every young African American—an important story, extremely well told, that should serve as a lesson on how we got here and where we need to go.” —Fred D. Gray, civil rights attorney for Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, and the Montgomery Bus Boycott

“Jackson is incisive […] he pulls no punches when discussing the racism he’s experience throughout his life, but remains determined to rise above. Readers will be inspired.” —Publisher's Weekly

“A valuable reminder of the invisible hurdles set in front of every young African American—an important story, extremely well told, that should serve as a lesson on how we got here and where we need to go.” —Fred D. Gray, civil rights attorney for Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, and the Montgomery Bus Boycott

“Jackson is incisive […] he pulls no punches when discussing the racism he’s experience throughout his life, but remains determined to rise above. Readers will be inspired.” —Publisher's Weekly

Descriere

A memoir of grit and perseverance as a pre-gentrified Brooklyn native overcomes meager beginnings to find comfort and success, from former entertainment attorney and current Microsoft Associate General Counsel, Bruce Jackson.