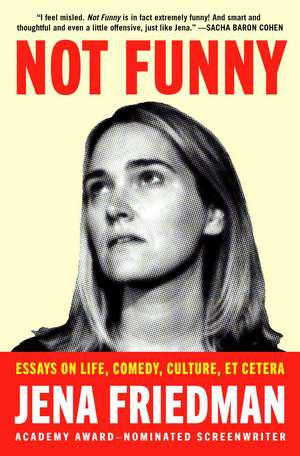

Not Funny: Essays on Life, Comedy, Culture, Et Cetera

Autor Jena Friedmanen Limba Engleză Hardback – 11 mai 2023

Jena Friedman’s life in comedy began with her senior thesis on inequity in the Chicago comedy scene. It was, in short, not funny, but it anticipated her career as a writer and comedian with acerbic wit and a keen, cutting eye for social observation. Now, she brings her trademark whip-smart humor and cultural criticism to this brainy and laugh-out-loud funny essay collection.

Friedman effortlessly takes us just beyond the edge of the uncomfortable with explorations on everything from why some celebrities get buried for their indiscretions while others get a second (third, and fourth…) chance, how we should think about lines of appropriateness crossed decades ago, living in the post- (post-) #MeToo world of today, and the power we hand to silence when we’re told not to joke about reproductive rights, gender, privilege, or class.

Not Funny is a witty and bold collection, challenging us to deeply consider why we do and do not laugh, from a rising star of comedy always ready to call out hypocrisy wherever she finds it. And knows how to get a laugh while she does it.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (1) | 69.69 lei 3-5 săpt. | +9.33 lei 4-10 zile |

| Atria/One Signal Publishers – 14 aug 2024 | 69.69 lei 3-5 săpt. | +9.33 lei 4-10 zile |

| Hardback (1) | 87.17 lei 25-37 zile | +37.63 lei 4-10 zile |

| Atria/One Signal Publishers – 11 mai 2023 | 87.17 lei 25-37 zile | +37.63 lei 4-10 zile |

Preț: 87.17 lei

Preț vechi: 108.30 lei

-20% Nou

Puncte Express: 131

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.69€ • 18.13$ • 14.02£

16.69€ • 18.13$ • 14.02£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 04-16 aprilie

Livrare express 14-20 martie pentru 47.62 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781982178284

ISBN-10: 1982178280

Pagini: 256

Ilustrații: b&w images throughout

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.4 kg

Editura: Atria/One Signal Publishers

Colecția Atria/One Signal Publishers

ISBN-10: 1982178280

Pagini: 256

Ilustrații: b&w images throughout

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.4 kg

Editura: Atria/One Signal Publishers

Colecția Atria/One Signal Publishers

Notă biografică

Jena Friedman is a comedian, filmmaker, and creator of AMC’s Indefensible and Soft Focus with Jena Friedman on Adult Swim. She has worked on The Daily Show with Jon Stewart and Late Show with David Letterman, and her writing has appeared in The New Yorker, Artnet, and The Guardian. She was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay and won a Writers Guild of America Award for her work on Borat Subsequent Moviefilm. She splits her time between Los Angeles and New York. Find out more at JenaFriedman.com and follow her on Twitter @JenaFriedman.

Extras

1. Not FunnyNot Funny

You don’t look funny. How the hell did you end up being a comedian?”

I get asked this question a lot, and every time I take it as a compliment. The short answer? I failed at every other job I tried.I The long answer is a little more complicated.

Part of the reason I titled this book Not FunnyII is because it perfectly encapsulates my origin story. It begins my senior year at Northwestern, while I was researching and writing my undergraduate thesis in cultural anthropology. The thesis was called “Whose Truth and Comedy: An Ethnography of Race, Class and Gender in Chicago’s Improv Comedy Scene,” and it was just as hilarious as it sounds.

The discipline of anthropology has a pretty shady history, involving white men with names like Bronislaw and Claude who traveled to remote villages in the farthest corners of the world to “study” the “natives” and then made careers out of writing racist ethnographies about their subjects. I didn’t want to go that route, so when it came time to find a topic for my yearlong ethnographic essay—a qualitative research project that involves immersing oneself in a community to observe their behaviors and interactions—I picked a tribe I thought I could blend into easily: female comedians.

I had always been fascinated by comedy, but my left-brained parents would never encourage me to pursue such an unorthodox and unstable profession. In fact, when I finally “came out” to my mother as a comedian, she treated the news like there had been a death in the family. “I’d rather you be gay,” she whimpered, “because at least that’s something you can’t control.” She was always the funny one.

At the time I was researching my thesis, I was living in Chicago with three friends who had all studied abroad in various countries the previous year. We built a bond on our life-changing experiences overseas (I had spent a semester in Santiago, Chile) and the determination to avoid moving back to our suburban campus, where social life was constructed around the fraternity basement beer-pong circuit. During the summer, we moved into a carriage house in the back of a bar on Halsted and Roscoe, a few blocks from the L train and an easy commute to our classes in Evanston.

Originally, I wanted to write my thesis about female stand-up comedians, but there was a dearth of women in stand-up comedy in Chicago back then and not enough of a sample size for me to study. There was also an improvisational comedy theater a few blocks from where I lived. I had no idea what improv was, but I had always been a sucker for anything within walking distance, and the place was always brimming with activity.

And just like that, I shifted my focus to improv. The site of my ethnography was called ImprovOlympic, later changed to iO after the International Olympic Committee threatened to sue. For a year it was my home—until it wasn’t.

You may have heard about iO from alums like Tina Fey, Amy Poehler, Mike Myers, Chris Farley, Tim Meadows, Adam McKay, or countless other famous comedians who have trained there. When I stumbled upon this cultIII—I mean “comedy theater and training center”—I had no idea what I was getting into. When I stopped by the place to see how much it would cost to purchase tickets to watch a bunch of shows, the young woman behind the desk—the hilarious Katie Rich, who later went on to write for Saturday Night Live—informed me that if I signed up for classes, I could see all the shows for free (that’s how they reel you in). I signed up for Level One Improv under the guise of “research,” and two months later, I was hooked.

Before improv became a punch line, largely due to the mainstream success of improviser-heavy hit shows like The Office and 30 Rock, Chicago’s improv comedy scene was the coolest thing I had ever been part of. The iO classes were full of such interesting and funny students. Many of them had moved to Chicago instead of or right after college to follow their dreams and pursue improv full-time. And my improv teachers were all really kind and encouraging, too. They were obsessed with the art form and always happy to talk to me about it over (many, many) drinks at the theater’s bar.

These were also the first adults I had ever met who had been able to make a living (in Chicago, which was an affordable city in 2005) out of teaching and playing what was essentially make believe for adults. Coming from my university, where most aspired to investment banking or consulting, this world felt like a much-needed breath of fresh air.

Most fascinating was long-form improv itself, a comedic, physically active art form that at its best evokes the pure, inspirational inventiveness of a jazz ensemble. The creative potential was limitless. You could be your own writer, performer, and director all at the same time. It felt as if a portal to another world had opened, and I never wanted to leave. To this day, I’ve never experienced as much unbridled joy as I did when creating something out of nothing with my friends and “teammates” onstage at iO.

It’s a shame that within a year the same research paper that lured me into this fascinating subculture would be what forced me out of it. My paper had unwittingly amounted to something no private business wants to see: an audit. I looked at this theater-slash-bar-slash-work-environment under a microscope, through a feminist-Marxist lens, and recorded what I found. Obviously, it pissed some people off.

ABSTRACT

Race, gender, and socioeconomic privilege are key elements in the production and consumption of long-form improvisational comedy in Chicago. The bulk of my research includes observations, interviews, and my own experiences performing and working at Chicago’s ImprovOlympic Theater and Training Center.

In this essay, I examine how college-educated white women have become a major force in Chicago’s improvisational comedy community, on and off the stage. I analyze the ways in which white women’s socialization into Chicago’s improvisational comedy scene differs from that of nonwhite men and women. I document the experiences of racially and ethnically marginalized individuals working in Chicago improv’s mainstream to reveal this improvised comedic performance as a reflection of societal inequalities in America’s urban political economy.

HA HA LOL! I know the paper sounds wonky, and that’s because it was. I wasn’t a comedian when I wrote my undergraduate thesis, just an overeager, idealistic college student trying to document an honest account of a lived experience under the guidance of a radical feminist–Marxist college adviser. We’ve all done crazy things in college, right?

Professor Micaela di Leonardo is a rock star in the field of cultural anthropology. I really wanted to impress her. She was beloved and equally feared by her students and would often make essays I turned in hemorrhage with red ink from her critical pen. I remember during our first class, she told her students about a pencil-drawing course she once took as a kid that taught her to draw. She explained that after a few classes, when she would look at a tree, she wouldn’t just see a tree but rather the series of pencil lines that would enable her to render the tree accurately on paper. That’s also how she explained feminist-Marxist anthropology. By teaching her students about race, gender, and structural inequality in certain populations, we would start to see it everywhere. She was right.

With Professor di Leonardo on board as my thesis adviser, I wasn’t just studying improv; I was looking at the ways in which the performance of Chicago-style long-form improvisational comedy and the culture around it reflected a stalled affirmative action agenda in a Bush-era political economy (I know, it’s a lot). Translation: Why, after so many decades of “social progress,” were these “liberal” spaces still so… white? She encouraged me to probe deeper into issues of structural inequality and not hold back when documenting my own enculturation into this magical but flawed subculture. Her teachings had a profound impact on me back then and are still evident in so much of my work to this day.

The thesis was well received, and I even worked toward graduating early from my anthropology program, with honors, so that I could dedicate even more time that spring and summer to my new drug—I mean improv comedy habit.

When a comedy blogger asked to read my thesis, I didn’t hesitate to share. Of course she could read my little college paper, a dry academic analysis of this comedy institution. What was the worst that could happen?

Man, was I wrong.

Once I gave the blogger permission to post my paper to her site, everyone in our tight-knit comedy scene read it. And because I had disguised my interview subjects’ identities through pseudonyms, all the criticism of the “controversial views” expressed throughout my thesis, mostly about racism and sexism I observed at iO, piled onto me.

The fallout was immediate, and in 2005, there was no social media to have my back (I never thought I’d write this, but sometimes social media can be harnessed for good!). Charna Halpern, the owner of the theater, canceled my weekly show from the calendar and kicked me off my improv team. A few days later, two of my favorite former (female) improv teachers called me on the phone and reprimanded me for writing about sexual harassment in my paper rather than keeping it under wraps and reporting it to them directly.

“Women in this community don’t make waves offstage,” one lectured as I struggled to hold back tears. “We make waves onstage.”

I was devastated, and I was confused. I never intended my college paper to make the people I admired and respected most in that scene so angry, or for it to alienate me from a world I had grown to love. Why was it the women in this community—Charna and my two female teachers—who were coming down on me the hardest?IV It would take me years to understand why they reacted the way they did, but at the time I felt like I had failed them, that it was I who had done something wrong.

One specific passage of the forty-three-page thesis seemed to provoke the most outrage. It was a short paragraph where I documented a minor encounter I had as an intern.

I was reading Barbara Bergmann’s The Economic Emergence of Women, specifically her chapter on sexual harassment in the workplace, while on my break between performance sets. I was wearing my red and black ImprovOlympic employee T-shirt when a male director and teacher at the theater approached me and initiated conversation by asking me what I was reading. He feigned acknowledgment of the author, grazed my lower back with his hand, and in all seriousness proceeded, “Does your hair naturally flip like that?” When I hesitated to respond, he continued, “Do you know how many women try to make their hair look like that?” I shrugged, laughed uncomfortably at his arbitrary remarks, and continued to read. After three months working at ImprovOlympic, I realized that my socialization offstage was interfering with my ability to “play” onstage. That is, as a female intern I could not repel frequent sexual harassment in the way that I would be expected to—“playing strong”—onstage. I ended my work-study internship prematurely because I had the economic means to pay for classes.

I specifically chose that anecdote to write about because it was so benign. I also found humor in the fact that I got lightly harassed while reading about sexual harassment, and I wanted to add some levity to the otherwise heavy subject matter. It’s not an easy topic to joke about, people!

But in reality, the harassment I experienced and observed during my internship at that theater was so much more insidious than what I had revealed in my report. Teachers often slept with students and in some cases, gave them stage time in return. Male and female interns were constantly groped and harassed in ways that I didn’t find offensive (compared to frat parties) but that I could see how other students might have.

Once when I was working, a male teacher pushed me into a storage closet and asked to feel my arm muscles. I thought it was weird, but I let him. I thought to myself, At least he asked, right? Male improvisers were often so handsy and boundaryless with female improvisers onstage that doing so offstage barely registered as inappropriate.

The subtle racism I witnessed at this very white comedy theater was worse. Onstage, white improvisers often tokenized their nonwhite scene partners to milk laughs out of mostly white audiences. Many marginalized students, men and women, ended up leaving the mainstream comedy theaters, like iO and Second City, to form their own separate improv troupes where they wouldn’t be subjected to constant racist microaggressions (and macroaggressions) from their mostly white improviser teammates or the mostly white crowds.

For decades, ImprovOlympic had been a pipeline to Saturday Night Live as well as many other major comedy career opportunities. If marginalized and underrepresented groups were being pushed out of this community before they ever got a chance to succeed, how did that affect mainstream production of comedy in the larger culture?

A journalist for the Chicago Reader reached out to interview me after she heard that backlash to the research paper got me kicked out of iO. I declined her request. I was afraid to speak to her. I didn’t want to “make waves offstage” or look like I was trying to get attention. I had already been made to feel like a traitor to a community that had been so welcoming to me, and I didn’t want to feel like that again.

I quietly made my exit from iO and looked for ways to get my improv fix elsewhere. For a little while, I performed improv with friends in bars and at smaller, less venerated improv clubs and black-box theaters around Chicago, but it wasn’t the same. Nothing could compare to the thrill of performing on a sold-out show on iO’s main stage. I still think about how different my career path might have been if I had just kept that paper to anthropology class and never unleashed it into the wilds of Chicago’s insular improv comedy community. If I hadn’t been blacklisted, maybe I would have eventually gotten more stage time at iO and possibly been invited to perform on one of many highly coveted industry showcases there. Maybe from there I could have gotten a job writing or performing on SNL, and hell, maybe now I’d be… probably fired from that hypothetical job at SNL. I hear it’s a tough place to work.

Once when I was a student intern at iO, I got an inside tip that Lorne Michaels was on his way to the theater that night to scout for potential cast members; Charna had set up a showcase of her favorite improvisers for him to check out. It was crazy to be a fly on the wall; I can still recall the nervous energy in the room as students crowded on the floor to watch our favorite improv heroes audition for the biggest role of their lives. Some veteran performers barely broke a sweat during their scenes, while others completely choked, all while Lorne sat in stone-faced judgment. While no one ended up getting their big break that night, years later some of my iO friends and heroes—Michael Patrick O’Brien, Vanessa Bayer, Paul Brittain, and Tim Robinson—would get the call to write and perform on SNL.

It was heartbreaking to leave that community, and I still get sad thinking about it, but if I hadn’t been cast out of my cushy, tight-knit improv bubble, I might never have had the guts to go out on my own. Over the next few years, I focused most of my creative energy on stand-up and sketch writing. The people who had been my friends at iO stayed my friends. After tensions had cooled, I would occasionally stop by the theater to see shows, but I never again performed at the place that I used to consider my second home.

A decade later, I came across an article about women in Chicago’s comedy scene fighting back against sexual harassment. The piece was about iO. In 2015 the sexual harassment that I had written about in my college paper had become the subject of multiple articles in mainstream news outlets like Jezebel, BuzzFeed, the Chicago Reader, and the Chicago Tribune. According to the pieces, iO management had ignored multiple reports of sexual harassment. When one student who had reported her sexual harassment demanded accountability, Charna—still a central figure at the club—offered her free classes. But this time, the student had the power to take the story to social media. Outraged, dozens of other students and former students came forward with their own experiences of sexual harassment at iO and at other comedy theaters in Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles.

Seeing all the press coverage felt vindicating, but it was also frustrating—a decade later, how could this all still be going on? Around that time, one of the female iO teachers who had initially reprimanded me when my paper first came out reached out on social media to say hi and to tell me that she was proud of all my success (her words; I will never not have imposter syndrome). She didn’t apologize for what she’d said to me years earlier, but she didn’t have to. I recognized what she must have been dealing with from her employer or whatever baggage she might have accumulated in her years in the trenches, and I didn’t hold it against her. It was also just nice to hear from her.

Comedy, and art in general, is often a step ahead of the culture, and although it was a few years shy of the explosion of the #MeToo movement, after that 2015 sexual harassment shitstorm at iO, some improv comedy clubs around the US finally began to take sexual harassment seriously.

At the Upright Citizens Brigade Theatre in New York, where I performed stand-up regularly, a male performer was kicked out of the community after being credibly accused of rape by multiple women who performed there. The guy ended up suing UCB for reverse gender discrimination (which sounds about right, the rapists always sue), and the court ultimately sided in the comedy club’s favor. The landmark ruling echoed throughout the whole community, finally providing a legal framework to make comedy clubs safer for the people who work and perform in those spaces.

At the time I write this, both iO Theaters in Chicago and Los Angeles, the Upright Citizens Brigade Theatres in New York and Los Angeles, and dozens of other performance venues around the country have shuttered in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic. But I have confidence they’ll be back, if nothing else, because cults are a proven and durable business model. And if not those actual theaters, some other incarnation of them will emerge on the scene. And I hope that when they do, the next crop of improv-comedy-theaters-slash-training-centers-slash-bars learn from the mistakes of their predecessors and make their spaces safer and more inclusive, at the very least so that their students can be spared from ever venturing into stand-up.

You don’t look funny. How the hell did you end up being a comedian?”

I get asked this question a lot, and every time I take it as a compliment. The short answer? I failed at every other job I tried.I The long answer is a little more complicated.

Part of the reason I titled this book Not FunnyII is because it perfectly encapsulates my origin story. It begins my senior year at Northwestern, while I was researching and writing my undergraduate thesis in cultural anthropology. The thesis was called “Whose Truth and Comedy: An Ethnography of Race, Class and Gender in Chicago’s Improv Comedy Scene,” and it was just as hilarious as it sounds.

The discipline of anthropology has a pretty shady history, involving white men with names like Bronislaw and Claude who traveled to remote villages in the farthest corners of the world to “study” the “natives” and then made careers out of writing racist ethnographies about their subjects. I didn’t want to go that route, so when it came time to find a topic for my yearlong ethnographic essay—a qualitative research project that involves immersing oneself in a community to observe their behaviors and interactions—I picked a tribe I thought I could blend into easily: female comedians.

I had always been fascinated by comedy, but my left-brained parents would never encourage me to pursue such an unorthodox and unstable profession. In fact, when I finally “came out” to my mother as a comedian, she treated the news like there had been a death in the family. “I’d rather you be gay,” she whimpered, “because at least that’s something you can’t control.” She was always the funny one.

At the time I was researching my thesis, I was living in Chicago with three friends who had all studied abroad in various countries the previous year. We built a bond on our life-changing experiences overseas (I had spent a semester in Santiago, Chile) and the determination to avoid moving back to our suburban campus, where social life was constructed around the fraternity basement beer-pong circuit. During the summer, we moved into a carriage house in the back of a bar on Halsted and Roscoe, a few blocks from the L train and an easy commute to our classes in Evanston.

Originally, I wanted to write my thesis about female stand-up comedians, but there was a dearth of women in stand-up comedy in Chicago back then and not enough of a sample size for me to study. There was also an improvisational comedy theater a few blocks from where I lived. I had no idea what improv was, but I had always been a sucker for anything within walking distance, and the place was always brimming with activity.

And just like that, I shifted my focus to improv. The site of my ethnography was called ImprovOlympic, later changed to iO after the International Olympic Committee threatened to sue. For a year it was my home—until it wasn’t.

You may have heard about iO from alums like Tina Fey, Amy Poehler, Mike Myers, Chris Farley, Tim Meadows, Adam McKay, or countless other famous comedians who have trained there. When I stumbled upon this cultIII—I mean “comedy theater and training center”—I had no idea what I was getting into. When I stopped by the place to see how much it would cost to purchase tickets to watch a bunch of shows, the young woman behind the desk—the hilarious Katie Rich, who later went on to write for Saturday Night Live—informed me that if I signed up for classes, I could see all the shows for free (that’s how they reel you in). I signed up for Level One Improv under the guise of “research,” and two months later, I was hooked.

Before improv became a punch line, largely due to the mainstream success of improviser-heavy hit shows like The Office and 30 Rock, Chicago’s improv comedy scene was the coolest thing I had ever been part of. The iO classes were full of such interesting and funny students. Many of them had moved to Chicago instead of or right after college to follow their dreams and pursue improv full-time. And my improv teachers were all really kind and encouraging, too. They were obsessed with the art form and always happy to talk to me about it over (many, many) drinks at the theater’s bar.

These were also the first adults I had ever met who had been able to make a living (in Chicago, which was an affordable city in 2005) out of teaching and playing what was essentially make believe for adults. Coming from my university, where most aspired to investment banking or consulting, this world felt like a much-needed breath of fresh air.

Most fascinating was long-form improv itself, a comedic, physically active art form that at its best evokes the pure, inspirational inventiveness of a jazz ensemble. The creative potential was limitless. You could be your own writer, performer, and director all at the same time. It felt as if a portal to another world had opened, and I never wanted to leave. To this day, I’ve never experienced as much unbridled joy as I did when creating something out of nothing with my friends and “teammates” onstage at iO.

It’s a shame that within a year the same research paper that lured me into this fascinating subculture would be what forced me out of it. My paper had unwittingly amounted to something no private business wants to see: an audit. I looked at this theater-slash-bar-slash-work-environment under a microscope, through a feminist-Marxist lens, and recorded what I found. Obviously, it pissed some people off.

ABSTRACT

Race, gender, and socioeconomic privilege are key elements in the production and consumption of long-form improvisational comedy in Chicago. The bulk of my research includes observations, interviews, and my own experiences performing and working at Chicago’s ImprovOlympic Theater and Training Center.

In this essay, I examine how college-educated white women have become a major force in Chicago’s improvisational comedy community, on and off the stage. I analyze the ways in which white women’s socialization into Chicago’s improvisational comedy scene differs from that of nonwhite men and women. I document the experiences of racially and ethnically marginalized individuals working in Chicago improv’s mainstream to reveal this improvised comedic performance as a reflection of societal inequalities in America’s urban political economy.

HA HA LOL! I know the paper sounds wonky, and that’s because it was. I wasn’t a comedian when I wrote my undergraduate thesis, just an overeager, idealistic college student trying to document an honest account of a lived experience under the guidance of a radical feminist–Marxist college adviser. We’ve all done crazy things in college, right?

Professor Micaela di Leonardo is a rock star in the field of cultural anthropology. I really wanted to impress her. She was beloved and equally feared by her students and would often make essays I turned in hemorrhage with red ink from her critical pen. I remember during our first class, she told her students about a pencil-drawing course she once took as a kid that taught her to draw. She explained that after a few classes, when she would look at a tree, she wouldn’t just see a tree but rather the series of pencil lines that would enable her to render the tree accurately on paper. That’s also how she explained feminist-Marxist anthropology. By teaching her students about race, gender, and structural inequality in certain populations, we would start to see it everywhere. She was right.

With Professor di Leonardo on board as my thesis adviser, I wasn’t just studying improv; I was looking at the ways in which the performance of Chicago-style long-form improvisational comedy and the culture around it reflected a stalled affirmative action agenda in a Bush-era political economy (I know, it’s a lot). Translation: Why, after so many decades of “social progress,” were these “liberal” spaces still so… white? She encouraged me to probe deeper into issues of structural inequality and not hold back when documenting my own enculturation into this magical but flawed subculture. Her teachings had a profound impact on me back then and are still evident in so much of my work to this day.

The thesis was well received, and I even worked toward graduating early from my anthropology program, with honors, so that I could dedicate even more time that spring and summer to my new drug—I mean improv comedy habit.

When a comedy blogger asked to read my thesis, I didn’t hesitate to share. Of course she could read my little college paper, a dry academic analysis of this comedy institution. What was the worst that could happen?

Man, was I wrong.

Once I gave the blogger permission to post my paper to her site, everyone in our tight-knit comedy scene read it. And because I had disguised my interview subjects’ identities through pseudonyms, all the criticism of the “controversial views” expressed throughout my thesis, mostly about racism and sexism I observed at iO, piled onto me.

The fallout was immediate, and in 2005, there was no social media to have my back (I never thought I’d write this, but sometimes social media can be harnessed for good!). Charna Halpern, the owner of the theater, canceled my weekly show from the calendar and kicked me off my improv team. A few days later, two of my favorite former (female) improv teachers called me on the phone and reprimanded me for writing about sexual harassment in my paper rather than keeping it under wraps and reporting it to them directly.

“Women in this community don’t make waves offstage,” one lectured as I struggled to hold back tears. “We make waves onstage.”

I was devastated, and I was confused. I never intended my college paper to make the people I admired and respected most in that scene so angry, or for it to alienate me from a world I had grown to love. Why was it the women in this community—Charna and my two female teachers—who were coming down on me the hardest?IV It would take me years to understand why they reacted the way they did, but at the time I felt like I had failed them, that it was I who had done something wrong.

One specific passage of the forty-three-page thesis seemed to provoke the most outrage. It was a short paragraph where I documented a minor encounter I had as an intern.

I was reading Barbara Bergmann’s The Economic Emergence of Women, specifically her chapter on sexual harassment in the workplace, while on my break between performance sets. I was wearing my red and black ImprovOlympic employee T-shirt when a male director and teacher at the theater approached me and initiated conversation by asking me what I was reading. He feigned acknowledgment of the author, grazed my lower back with his hand, and in all seriousness proceeded, “Does your hair naturally flip like that?” When I hesitated to respond, he continued, “Do you know how many women try to make their hair look like that?” I shrugged, laughed uncomfortably at his arbitrary remarks, and continued to read. After three months working at ImprovOlympic, I realized that my socialization offstage was interfering with my ability to “play” onstage. That is, as a female intern I could not repel frequent sexual harassment in the way that I would be expected to—“playing strong”—onstage. I ended my work-study internship prematurely because I had the economic means to pay for classes.

I specifically chose that anecdote to write about because it was so benign. I also found humor in the fact that I got lightly harassed while reading about sexual harassment, and I wanted to add some levity to the otherwise heavy subject matter. It’s not an easy topic to joke about, people!

But in reality, the harassment I experienced and observed during my internship at that theater was so much more insidious than what I had revealed in my report. Teachers often slept with students and in some cases, gave them stage time in return. Male and female interns were constantly groped and harassed in ways that I didn’t find offensive (compared to frat parties) but that I could see how other students might have.

Once when I was working, a male teacher pushed me into a storage closet and asked to feel my arm muscles. I thought it was weird, but I let him. I thought to myself, At least he asked, right? Male improvisers were often so handsy and boundaryless with female improvisers onstage that doing so offstage barely registered as inappropriate.

The subtle racism I witnessed at this very white comedy theater was worse. Onstage, white improvisers often tokenized their nonwhite scene partners to milk laughs out of mostly white audiences. Many marginalized students, men and women, ended up leaving the mainstream comedy theaters, like iO and Second City, to form their own separate improv troupes where they wouldn’t be subjected to constant racist microaggressions (and macroaggressions) from their mostly white improviser teammates or the mostly white crowds.

For decades, ImprovOlympic had been a pipeline to Saturday Night Live as well as many other major comedy career opportunities. If marginalized and underrepresented groups were being pushed out of this community before they ever got a chance to succeed, how did that affect mainstream production of comedy in the larger culture?

A journalist for the Chicago Reader reached out to interview me after she heard that backlash to the research paper got me kicked out of iO. I declined her request. I was afraid to speak to her. I didn’t want to “make waves offstage” or look like I was trying to get attention. I had already been made to feel like a traitor to a community that had been so welcoming to me, and I didn’t want to feel like that again.

I quietly made my exit from iO and looked for ways to get my improv fix elsewhere. For a little while, I performed improv with friends in bars and at smaller, less venerated improv clubs and black-box theaters around Chicago, but it wasn’t the same. Nothing could compare to the thrill of performing on a sold-out show on iO’s main stage. I still think about how different my career path might have been if I had just kept that paper to anthropology class and never unleashed it into the wilds of Chicago’s insular improv comedy community. If I hadn’t been blacklisted, maybe I would have eventually gotten more stage time at iO and possibly been invited to perform on one of many highly coveted industry showcases there. Maybe from there I could have gotten a job writing or performing on SNL, and hell, maybe now I’d be… probably fired from that hypothetical job at SNL. I hear it’s a tough place to work.

Once when I was a student intern at iO, I got an inside tip that Lorne Michaels was on his way to the theater that night to scout for potential cast members; Charna had set up a showcase of her favorite improvisers for him to check out. It was crazy to be a fly on the wall; I can still recall the nervous energy in the room as students crowded on the floor to watch our favorite improv heroes audition for the biggest role of their lives. Some veteran performers barely broke a sweat during their scenes, while others completely choked, all while Lorne sat in stone-faced judgment. While no one ended up getting their big break that night, years later some of my iO friends and heroes—Michael Patrick O’Brien, Vanessa Bayer, Paul Brittain, and Tim Robinson—would get the call to write and perform on SNL.

It was heartbreaking to leave that community, and I still get sad thinking about it, but if I hadn’t been cast out of my cushy, tight-knit improv bubble, I might never have had the guts to go out on my own. Over the next few years, I focused most of my creative energy on stand-up and sketch writing. The people who had been my friends at iO stayed my friends. After tensions had cooled, I would occasionally stop by the theater to see shows, but I never again performed at the place that I used to consider my second home.

A decade later, I came across an article about women in Chicago’s comedy scene fighting back against sexual harassment. The piece was about iO. In 2015 the sexual harassment that I had written about in my college paper had become the subject of multiple articles in mainstream news outlets like Jezebel, BuzzFeed, the Chicago Reader, and the Chicago Tribune. According to the pieces, iO management had ignored multiple reports of sexual harassment. When one student who had reported her sexual harassment demanded accountability, Charna—still a central figure at the club—offered her free classes. But this time, the student had the power to take the story to social media. Outraged, dozens of other students and former students came forward with their own experiences of sexual harassment at iO and at other comedy theaters in Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles.

Seeing all the press coverage felt vindicating, but it was also frustrating—a decade later, how could this all still be going on? Around that time, one of the female iO teachers who had initially reprimanded me when my paper first came out reached out on social media to say hi and to tell me that she was proud of all my success (her words; I will never not have imposter syndrome). She didn’t apologize for what she’d said to me years earlier, but she didn’t have to. I recognized what she must have been dealing with from her employer or whatever baggage she might have accumulated in her years in the trenches, and I didn’t hold it against her. It was also just nice to hear from her.

Comedy, and art in general, is often a step ahead of the culture, and although it was a few years shy of the explosion of the #MeToo movement, after that 2015 sexual harassment shitstorm at iO, some improv comedy clubs around the US finally began to take sexual harassment seriously.

At the Upright Citizens Brigade Theatre in New York, where I performed stand-up regularly, a male performer was kicked out of the community after being credibly accused of rape by multiple women who performed there. The guy ended up suing UCB for reverse gender discrimination (which sounds about right, the rapists always sue), and the court ultimately sided in the comedy club’s favor. The landmark ruling echoed throughout the whole community, finally providing a legal framework to make comedy clubs safer for the people who work and perform in those spaces.

At the time I write this, both iO Theaters in Chicago and Los Angeles, the Upright Citizens Brigade Theatres in New York and Los Angeles, and dozens of other performance venues around the country have shuttered in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic. But I have confidence they’ll be back, if nothing else, because cults are a proven and durable business model. And if not those actual theaters, some other incarnation of them will emerge on the scene. And I hope that when they do, the next crop of improv-comedy-theaters-slash-training-centers-slash-bars learn from the mistakes of their predecessors and make their spaces safer and more inclusive, at the very least so that their students can be spared from ever venturing into stand-up.

Recenzii

"In fact very funny. And [Friedman] somehow manages to do that while taking on some of the, shall we say, darker topics, like sexism, celebrity worship, and women's rights."

—Cosmopolitan

“Not Funny feels as if you're having a direct conversation with Jena. A mix of lethal deadpan delivery and biting sarcasm with impressive intelligence not only makes this book phenomenal, but announces the arrival of a singular voice." —Phoebe Robinson, New York TImes bestselling author of You Can't Touch My Hair

“Jena Friedman is brilliant at mining the darkness for a joke you'd never dare say, that makes you jealous you didn't think of it yourself. I am here for every word of this hilarious and much needed book.” —Samantha Bee, Emmy Award-winning comedian, actor, commentator and author of I Know I Am, But What Are You?

“I feel misled. Not Funny is in fact extremely funny! And smart and thoughtful and even a little offensive, just like Jena” —Sacha Baron Cohen, actor, writer, producer, and creator and star of Borat

“Jena dares you to laugh at things we're told not to laugh at, perhaps because that's how they keep us from seeing the truth. A page-turner through and through: Just when I'm thinking 'it can't be!' Jena tells you it is. And I'm laughing through it. Jena proves with her writing that not only is laughing at dark truths important, it's revolutionary.”

—Atsuko Okatsuka, comedian, actress, and writer

“I’ve skimmed this book and it seems pretty funny. I have every intention of reading it as soon as I finish The History of The Decline and Fall of The Roman Empire.” —Larry David, writer, actor, and co-creator of Seinfeld and Curb Your Enthusiasm

“Jena’s comedy is and has always been radical. She’s dark, unapologetic, and biting. It’s really funny and a little frightening.” —Ilana Glazer, actor, writer, and co-creator of Broad City

“From her sharp and fearless comedy specials, to the deadpan interviews in which she expertly skewers a fine array of sexist miscreants, Jena Friedman is actually not funny--she is hilarious and brilliant.” —Merrill Markoe, New York Times bestselling author of Walking in Circles Before Lying Down

"A funny but critical look at the depradations of life as a woman comic [...] A serious memoir with jokes, self-deprecating yet rarely self-diminishing.”

—Kirkus

"[Jena Friedman] sparkles with the casual brilliance of fellow comedians and humor essayists Lindy West and Sarah Silverman."

—Library Journal

"Entertaining and soulful... this is a blast."

—Publishers Weekly

"Don’t let the footnotes fool you; this isn’t a dry academic treatise. . . . Perfect for fans of dark, feminist comedy such as Hannah Gadsby or Samantha Bee."

—Booklist

"It's no slight against comedian Jena Friedman to say that the title of her first book should be taken largely at face value. . . . For an injection of power and agency, readers could scarcely do better than Not Funny."

—Shelf Awareness

"Jena's always been fiercely honest both onstage and off, and this book is no exception. If you want to laugh and scream, give NOT FUNNY a read."

—Naomi Ekperigin, comedian, actress, and writer

—Cosmopolitan

“Not Funny feels as if you're having a direct conversation with Jena. A mix of lethal deadpan delivery and biting sarcasm with impressive intelligence not only makes this book phenomenal, but announces the arrival of a singular voice." —Phoebe Robinson, New York TImes bestselling author of You Can't Touch My Hair

“Jena Friedman is brilliant at mining the darkness for a joke you'd never dare say, that makes you jealous you didn't think of it yourself. I am here for every word of this hilarious and much needed book.” —Samantha Bee, Emmy Award-winning comedian, actor, commentator and author of I Know I Am, But What Are You?

“I feel misled. Not Funny is in fact extremely funny! And smart and thoughtful and even a little offensive, just like Jena” —Sacha Baron Cohen, actor, writer, producer, and creator and star of Borat

“Jena dares you to laugh at things we're told not to laugh at, perhaps because that's how they keep us from seeing the truth. A page-turner through and through: Just when I'm thinking 'it can't be!' Jena tells you it is. And I'm laughing through it. Jena proves with her writing that not only is laughing at dark truths important, it's revolutionary.”

—Atsuko Okatsuka, comedian, actress, and writer

“I’ve skimmed this book and it seems pretty funny. I have every intention of reading it as soon as I finish The History of The Decline and Fall of The Roman Empire.” —Larry David, writer, actor, and co-creator of Seinfeld and Curb Your Enthusiasm

“Jena’s comedy is and has always been radical. She’s dark, unapologetic, and biting. It’s really funny and a little frightening.” —Ilana Glazer, actor, writer, and co-creator of Broad City

“From her sharp and fearless comedy specials, to the deadpan interviews in which she expertly skewers a fine array of sexist miscreants, Jena Friedman is actually not funny--she is hilarious and brilliant.” —Merrill Markoe, New York Times bestselling author of Walking in Circles Before Lying Down

"A funny but critical look at the depradations of life as a woman comic [...] A serious memoir with jokes, self-deprecating yet rarely self-diminishing.”

—Kirkus

"[Jena Friedman] sparkles with the casual brilliance of fellow comedians and humor essayists Lindy West and Sarah Silverman."

—Library Journal

"Entertaining and soulful... this is a blast."

—Publishers Weekly

"Don’t let the footnotes fool you; this isn’t a dry academic treatise. . . . Perfect for fans of dark, feminist comedy such as Hannah Gadsby or Samantha Bee."

—Booklist

"It's no slight against comedian Jena Friedman to say that the title of her first book should be taken largely at face value. . . . For an injection of power and agency, readers could scarcely do better than Not Funny."

—Shelf Awareness

"Jena's always been fiercely honest both onstage and off, and this book is no exception. If you want to laugh and scream, give NOT FUNNY a read."

—Naomi Ekperigin, comedian, actress, and writer

Descriere

For fans of the perceptive comedy of Hannah Gadsby, Lindy West, and Sarah Silverman, Academy Award–nominated and acclaimed stand-up comedian Jena Friedman presents a witty and insightful collection of essays on the cultural flashpoints of today.