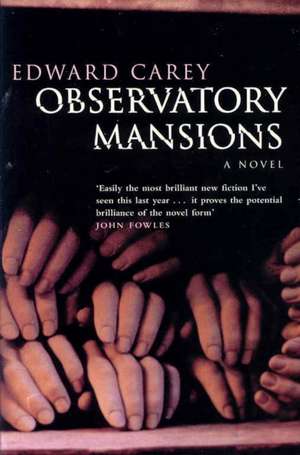

Observatory Mansions

Autor Edward Careyen Limba Engleză Paperback – 21 mar 2019

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 45.01 lei 22-36 zile | +31.64 lei 6-12 zile |

| Pan Macmillan – 21 mar 2019 | 45.01 lei 22-36 zile | +31.64 lei 6-12 zile |

| Vintage Publishing – 31 ian 2002 | 95.45 lei 22-36 zile |

Preț: 45.01 lei

Preț vechi: 64.39 lei

-30% Nou

Puncte Express: 68

Preț estimativ în valută:

8.61€ • 9.02$ • 7.17£

8.61€ • 9.02$ • 7.17£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 10-24 martie

Livrare express 22-28 februarie pentru 41.63 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781529031331

ISBN-10: 1529031338

Pagini: 368

Dimensiuni: 133 x 195 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: Pan Macmillan

ISBN-10: 1529031338

Pagini: 368

Dimensiuni: 133 x 195 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: Pan Macmillan

Notă biografică

Edward Carey is a novelist, visual artist and playwright. Born in England, Edward Carey teaches Creative Writing at the University of Austin, Texas. He was awarded the prestigious Italian Fernanda Pivano Prize in 2016. His novels include Observatory Mansions, Alva & Irva, The Iremonger Trilogy, Little, and The Swallowed Man.

Descriere

Edward Carey's debut is a novel of immense originality - a strangely haunting landscape occupied by compelling and unforgettable characters.

Extras

Our first rumour of the new resident came to us in the form of a little note pinned on to the noticeboard in the entrance hall. It said:

Flat 18 —

To be occupied.

One week.

A simple note that filled us with fear. The Porter placed the note there. He knew what we wanted to know: we wanted to know who it was that wanted to occupy flat eighteen. He placed the note there because he knew it would upset us. He could merely have kept quiet and a week later we would be stunned to hear someone busy about the living business in flat eighteen, unannounced. But he warned us, knowing how it would upset us. His only motive was to upset us. He knew that we would all separately be spending the week worrying over the mysterious person who was to occupy flat eighteen, and that he alone would keep the secret because no one ever spoke to him.

The Porter would not open his mouth, except to hiss. The Porter hissed at us if we came too near to him. That hiss meant — Go away. And we did. It was not pleasant to come too close to the Porter’s hiss. It was not pleasant to come too close to the Porter. So even if we had enquired about the new resident the reply would have been a hiss. Go away. We had to wait. And more than anything we hated waiting. Suspense was bad for our unfit hearts. We were left to imagine the future occupant of flat eighteen — for a whole week.

And for a whole week we were terrified. We slept short nights. We would find each other examining flat eighteen, as if by simply being in that specific section of the building which filled us with disquiet we would immediately understand what sort of person it was that was soon to occupy it. When we saw each other there we backed away, ashamed. If we entered the flat while the Porter was cleaning it, he would hiss us out of the place. We would run back to our own homes, shaking.

… A bespectacled blur.

When I returned from work, I climbed the stairs past flat six, where I lived with my parents, up to the third floor. The door of flat eighteen was closed. The new occupant had occupied. The door was shut and I did not knock to introduce myself. I put my ear to the door. I heard nothing. All that I could hear on the third floor was Miss Higg’s television set.

I returned home.

I had a visitor.

The visitor, who also kept a key to our flat, had let himself in. He was sitting in our largest room, a room that was a kitchen, a dining room and a sitting room. He was sitting on an upright pine chair facing a large red leather armchair. He was holding the hand of Father sitting in his armchair. The visitor was crying and sweating and smelling of a hundred different smells: Peter Bugg. Beads of sweat, islands, a-top his white shining skull.

Peter Bugg proceeded to tell me about the person who had occupied flat eighteen. I knew this was the reason for his visit. He did not usually come to me on that day. He arrived, punctually, twice a week to help me change Father. And he looked in on Father when I was at work (Mother, who lived in the largest bedroom of our flat, mercifully changed herself). Peter Bugg’s visit was an exception then. Peter Bugg spoke.

The new resident in flat eighteen, he explained, was not:

Old.

Dying.

Male.

The first two I had, I suppose, been expecting. It was unlikely that we would be so fortunate. The third was a shock. I had always considered that my imaginings of the new resident might be wildly inaccurate. I tried to allow for that. But I had never considered, even for a moment, that the new resident would be a female. As to whether she was pretty, ugly, obese, skeletal, slim, freckled, fair-skinned or dark, Peter Bugg was unable to inform me. Nor could he remember her age.

I can see her. I just can’t see what it is that I should see, what it is that I should describe.

What do you see?

I see … I see … a vague mass. Blurred. The mass was smoking a cigarette. There was smoke in my eyes. I was crying. Wait! There were two slight reflections around the region of the head. Yes! She was wearing spectacles.

Anything more? There must be more.

The poor weeping bundle had never, he elucidated, never been able to focus his eyes around the female form. It was a complete mystery to him. Even his mother? His mother, yes, he could remember better. She was the one married to his father, wasn’t she? Yes, he supposed that was her. A vague, well-meaning fog.

It transpired that Peter Bugg had met the new resident on the stairs and even spoken to her. He saw immediately, though not precisely, that she was not the sort of resident we could ever be happy with and told her so. He had twisted his face into a mask of bitterness and hate, a particular expression that had always horrified his pupils, and pointed words decisively and unpleasantly around the place whre he believed a head might normally be expected to be placed on the female anatomy.

Go back to your home. Go away.

And Peter Bugg believed that his intentions had been perfectly met in those two sentences. He was quite satisfied. But he had not expected a reply:

This is my home now.

It was her home now, she announced, and apparently she considered it to be. She continued up the stairs. Peter Bugg, appalled by her response, found himself a virtual waterfall of sweat and tears and nervously scrambled back into his home, flat ten.

Frustrated by the selective nature of Bugg’s remembrances, I decided the first night that the new resident of flat eighteen spent with us to call on someone else in Observatory Mansions to try and discover more. We would visit Miss Higg of flat sixteen. But not immediately since it was then the time when Miss Higg would be watching one of her favourite transmissions and we would certainly not be granted admission. We would politely wait until the transmission had finished. We ate. Why, I wondered aloud, and I had never considered this before, why was it that Peter Bugg could so effortlessly spend time with Miss Higg? She was, after all, female. He winced, sighed and then explained:

I have never considered there to be anything remotely feminine about Claire Higg.

Flat 18 —

To be occupied.

One week.

A simple note that filled us with fear. The Porter placed the note there. He knew what we wanted to know: we wanted to know who it was that wanted to occupy flat eighteen. He placed the note there because he knew it would upset us. He could merely have kept quiet and a week later we would be stunned to hear someone busy about the living business in flat eighteen, unannounced. But he warned us, knowing how it would upset us. His only motive was to upset us. He knew that we would all separately be spending the week worrying over the mysterious person who was to occupy flat eighteen, and that he alone would keep the secret because no one ever spoke to him.

The Porter would not open his mouth, except to hiss. The Porter hissed at us if we came too near to him. That hiss meant — Go away. And we did. It was not pleasant to come too close to the Porter’s hiss. It was not pleasant to come too close to the Porter. So even if we had enquired about the new resident the reply would have been a hiss. Go away. We had to wait. And more than anything we hated waiting. Suspense was bad for our unfit hearts. We were left to imagine the future occupant of flat eighteen — for a whole week.

And for a whole week we were terrified. We slept short nights. We would find each other examining flat eighteen, as if by simply being in that specific section of the building which filled us with disquiet we would immediately understand what sort of person it was that was soon to occupy it. When we saw each other there we backed away, ashamed. If we entered the flat while the Porter was cleaning it, he would hiss us out of the place. We would run back to our own homes, shaking.

… A bespectacled blur.

When I returned from work, I climbed the stairs past flat six, where I lived with my parents, up to the third floor. The door of flat eighteen was closed. The new occupant had occupied. The door was shut and I did not knock to introduce myself. I put my ear to the door. I heard nothing. All that I could hear on the third floor was Miss Higg’s television set.

I returned home.

I had a visitor.

The visitor, who also kept a key to our flat, had let himself in. He was sitting in our largest room, a room that was a kitchen, a dining room and a sitting room. He was sitting on an upright pine chair facing a large red leather armchair. He was holding the hand of Father sitting in his armchair. The visitor was crying and sweating and smelling of a hundred different smells: Peter Bugg. Beads of sweat, islands, a-top his white shining skull.

Peter Bugg proceeded to tell me about the person who had occupied flat eighteen. I knew this was the reason for his visit. He did not usually come to me on that day. He arrived, punctually, twice a week to help me change Father. And he looked in on Father when I was at work (Mother, who lived in the largest bedroom of our flat, mercifully changed herself). Peter Bugg’s visit was an exception then. Peter Bugg spoke.

The new resident in flat eighteen, he explained, was not:

Old.

Dying.

Male.

The first two I had, I suppose, been expecting. It was unlikely that we would be so fortunate. The third was a shock. I had always considered that my imaginings of the new resident might be wildly inaccurate. I tried to allow for that. But I had never considered, even for a moment, that the new resident would be a female. As to whether she was pretty, ugly, obese, skeletal, slim, freckled, fair-skinned or dark, Peter Bugg was unable to inform me. Nor could he remember her age.

I can see her. I just can’t see what it is that I should see, what it is that I should describe.

What do you see?

I see … I see … a vague mass. Blurred. The mass was smoking a cigarette. There was smoke in my eyes. I was crying. Wait! There were two slight reflections around the region of the head. Yes! She was wearing spectacles.

Anything more? There must be more.

The poor weeping bundle had never, he elucidated, never been able to focus his eyes around the female form. It was a complete mystery to him. Even his mother? His mother, yes, he could remember better. She was the one married to his father, wasn’t she? Yes, he supposed that was her. A vague, well-meaning fog.

It transpired that Peter Bugg had met the new resident on the stairs and even spoken to her. He saw immediately, though not precisely, that she was not the sort of resident we could ever be happy with and told her so. He had twisted his face into a mask of bitterness and hate, a particular expression that had always horrified his pupils, and pointed words decisively and unpleasantly around the place whre he believed a head might normally be expected to be placed on the female anatomy.

Go back to your home. Go away.

And Peter Bugg believed that his intentions had been perfectly met in those two sentences. He was quite satisfied. But he had not expected a reply:

This is my home now.

It was her home now, she announced, and apparently she considered it to be. She continued up the stairs. Peter Bugg, appalled by her response, found himself a virtual waterfall of sweat and tears and nervously scrambled back into his home, flat ten.

Frustrated by the selective nature of Bugg’s remembrances, I decided the first night that the new resident of flat eighteen spent with us to call on someone else in Observatory Mansions to try and discover more. We would visit Miss Higg of flat sixteen. But not immediately since it was then the time when Miss Higg would be watching one of her favourite transmissions and we would certainly not be granted admission. We would politely wait until the transmission had finished. We ate. Why, I wondered aloud, and I had never considered this before, why was it that Peter Bugg could so effortlessly spend time with Miss Higg? She was, after all, female. He winced, sighed and then explained:

I have never considered there to be anything remotely feminine about Claire Higg.

Recenzii

“A sublime take on the Gothic horror novel, an endearing love story…and a triumphant argument for how brilliant the novel can still be.”–Detroit Free Press

“Readers who complain there’s no originality left in the world should visit Observatory Mansions.”–USA Today

“A funny, sad, and provocative novel.”–The Washington Post Book World

“Observatory Mansions is a strange and beautiful book. . . . That this is a first novel is a wonder.” —The Memphis Flyer

“Readers who complain there’s no originality left in the world should visit Observatory Mansions.”–USA Today

“A funny, sad, and provocative novel.”–The Washington Post Book World

“Observatory Mansions is a strange and beautiful book. . . . That this is a first novel is a wonder.” —The Memphis Flyer