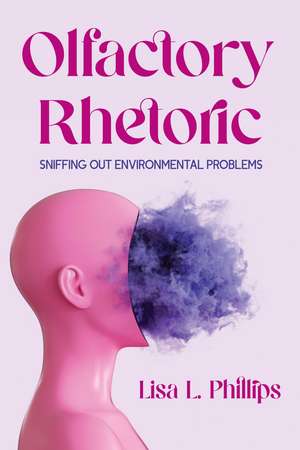

Olfactory Rhetoric: Sniffing Out Environmental Problems: New Directions in Rhetoric and Materiality

Autor Lisa L. Phillipsen Limba Engleză Paperback – 7 aug 2025

Human senses have the potential to play a significant role in inspiring action to combat climate change. When we smell pollutants in the air, for example, or feel the blast of a polar vortex, we are more likely to act in response to these changes in environmental conditions. However, the sensorium—and particularly our sense of smell—is often downplayed when we consider the rhetorics of environmental crises. In Olfactory Rhetoric, Lisa L. Phillips argues that how we sense the world around us should be a crucial piece of rhetorical evidence when evaluating environmental injustices. Specifically, Phillips elevates olfaction (what we smell) and olfactory rhetoric (how we talk about and experience what we smell) when discussing three contemporary environmental crises set in historically marginalized communities: the Sriracha sauce factory controversy, the Salton Sea scent events, and the Blue Ridge Landfill emissions problem. On a broader scale, Phillips develops an intersectional ecofeminist sensory-rhetorical approach for evaluating how olfactory and sensory persuasions work and how they can be used to advocate for environmental justice and a more breathable future.

Preț: 278.27 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 417

Preț estimativ în valută:

53.25€ • 58.02$ • 44.87£

53.25€ • 58.02$ • 44.87£

Carte nepublicată încă

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780814259535

ISBN-10: 0814259537

Pagini: 216

Ilustrații: 2 b&w images, 4 maps

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 mm

Greutate: 0.45 kg

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Ohio State University Press

Seria New Directions in Rhetoric and Materiality

ISBN-10: 0814259537

Pagini: 216

Ilustrații: 2 b&w images, 4 maps

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 mm

Greutate: 0.45 kg

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Ohio State University Press

Seria New Directions in Rhetoric and Materiality

Recenzii

“Olfactory Rhetoric clarifies the necessity of including the sensorium as rhetorical evidence, especially when considering environmental problems. Phillips’s intriguing neologisms like lungscape, smellscape, nosewitnessing, and nosesay will help material rhetorical scholars rethink how our language constructs ocular and language-based biases.” —Emma Frances Bloomfield, author of Science v. Story: Narrative Strategies for Science Communicators

Notă biografică

Lisa L. Phillips is Assistant Professor of English in the Technical Communication and Rhetoric Program at Texas Tech University. She is the coeditor of Grassroots Activisms: Public Rhetorics in Localized Contexts.

Extras

Mediated sensation—technological and fleshy—is the object of this book. Olfaction’s suasive nature and olfactory rhetoric are its subjects. Inciting a riot of “breathable futures” is the aim. Invoking sensation respects embodied experiences of people, nonhumans, and “elemental entities” in our shared molecular melee. Composite sensations—clusters of sensuous activity—unfold in the sensorium and mediated public sphere when environmental problems attract attention and spark future-oriented efforts through deliberative, epideictic, and forensic rhetorics. Deliberative rhetoric grapples with present and future actions and potential outcomes. Epideictic rhetoric assigns praise and/or blame to actors or agents in a network, and it is “a form of social action” meant to instruct publics about future a/effects and past practices. Forensic rhetoric pertains to legal cases, policy debates, grievance hearings, and more directed toward justice, though “justice” bears the unmistakable stamp of socioeconomic and political power. All three are informed by and through sensation. Like Jenny Rice, I link epideictic rhetoric and public memory to current and future deeds among emplaced, embodied publics. Like me, Rice is “interested in how to intervene in the negative aspects of development,” which include harmful environmental results from industrial processes, fast capitalism, racism, colonialism, and a host of associated concerns including unprecedented fossil fuel–driven global heating. However, rather than argue for “more investment” in “ongoing scene[s] of debate” imagined to foster “sustainable futures,” Rice suggests we disrupt “citizen nonparticipation” and circumvent old discursive debates. We can out-logic or out-argue one another, yet the world still burns replete with fumes of our own design.

This book shows how people, nonhumans, and more-than-humans are sensitive to environmental issues beyond words, illustrating how people can sense “themselves as public subjects who can and [do] intervene in . . . crises we currently face.” Facing Eastern ontologies and Luce Irigaray’s “respiratory lens,” or to avoid the ocularcentric context, a respiratory sensitivity seems fitting to the task of resuscitating Earth’s clogged airways and other bloody tributaries in need of CPR. In ashen corners where a section of the planetary lungscape collapsed, or an artery clogged, as representative of this book’s case study chapters, we need socially just ways to treat and evaluate the effects of decades of tar and other toxins on Earth’s life support system. We also need ways to unpack the mediating role of sensory persuasion as it bumps up against the “Technopolis,” a space of unrelenting “progress” in which the senses diminish in influence though not in import.

To begin, presuppose two ideas. First, assume nondiscursive sensation and our senses are rhetorical and at work in public memory of environmental hazards. Nondiscursive sensation, or what Debra Hawhee might name the “other than rational,” plays a role in deliberative, epideictic, and forensic acts because it persuades people to do or say something about an environmental issue. Public memory as it relates to nondiscursive sensation relies on the “activity of collectivity . . . in addition to individuated, cognitive work.” Second, consider odors rhetorical. People design and create smellscapes and scents for a variety of persuasive purposes, including to attract, sell, soothe, teach, motivate, delight, warn, threaten, disgust, and disguise. Though truncated, the list shows openings for rhetorical awareness that I address in detail in the “Why Olfaction Matters” section. Nonhuman animals and plants also create and exude odors to persuade. Encountering a skunk’s hindquarters when raised and aimed is one example that may tap some readers’ olfactory imaginations. In the plant realm, the corpse flower (Amorphophallus titanum) fills the air with a putrid smell to attract carnivorous insects, and the dark burgundy color of the flower looks tasty to pollinators. Using thermoregulation, the world’s largest flower can even warm itself up to 98°F (36.7°C) to further tickle a bug’s fancy and spread its smell through self-generated rarefied air. Such marvelous cookery, no?

This book shows how people, nonhumans, and more-than-humans are sensitive to environmental issues beyond words, illustrating how people can sense “themselves as public subjects who can and [do] intervene in . . . crises we currently face.” Facing Eastern ontologies and Luce Irigaray’s “respiratory lens,” or to avoid the ocularcentric context, a respiratory sensitivity seems fitting to the task of resuscitating Earth’s clogged airways and other bloody tributaries in need of CPR. In ashen corners where a section of the planetary lungscape collapsed, or an artery clogged, as representative of this book’s case study chapters, we need socially just ways to treat and evaluate the effects of decades of tar and other toxins on Earth’s life support system. We also need ways to unpack the mediating role of sensory persuasion as it bumps up against the “Technopolis,” a space of unrelenting “progress” in which the senses diminish in influence though not in import.

To begin, presuppose two ideas. First, assume nondiscursive sensation and our senses are rhetorical and at work in public memory of environmental hazards. Nondiscursive sensation, or what Debra Hawhee might name the “other than rational,” plays a role in deliberative, epideictic, and forensic acts because it persuades people to do or say something about an environmental issue. Public memory as it relates to nondiscursive sensation relies on the “activity of collectivity . . . in addition to individuated, cognitive work.” Second, consider odors rhetorical. People design and create smellscapes and scents for a variety of persuasive purposes, including to attract, sell, soothe, teach, motivate, delight, warn, threaten, disgust, and disguise. Though truncated, the list shows openings for rhetorical awareness that I address in detail in the “Why Olfaction Matters” section. Nonhuman animals and plants also create and exude odors to persuade. Encountering a skunk’s hindquarters when raised and aimed is one example that may tap some readers’ olfactory imaginations. In the plant realm, the corpse flower (Amorphophallus titanum) fills the air with a putrid smell to attract carnivorous insects, and the dark burgundy color of the flower looks tasty to pollinators. Using thermoregulation, the world’s largest flower can even warm itself up to 98°F (36.7°C) to further tickle a bug’s fancy and spread its smell through self-generated rarefied air. Such marvelous cookery, no?

Cuprins

List of Illustrations Preface Environmental Injustice Stinks List of Abbreviations Introduction Rhetoric Comes to Its Senses Chapter 1 Proposing a Sensory Rhetorical Approach to Environmental Problems Chapter 2 Is It Pepper Spray or Sriracha Sauce? Chapter 3 Something Smells Fishy at the Salton Sea Chapter 4 Nasal Rangers at the Blue Ridge Landfill Chapter 5 Launching a Call to Sense Acknowledgments Works Cited Index

Descriere

Defines, describes, and deploys olfactory rhetoric to argue that how we sense the world around us offers crucial rhetorical evidence when evaluating environmental injustices.