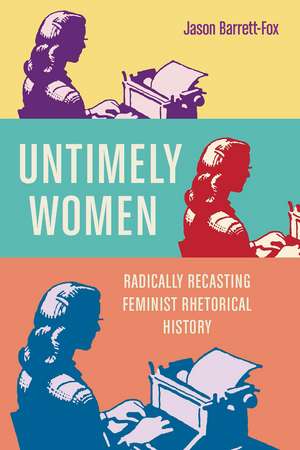

Untimely Women: Radically Recasting Feminist Rhetorical History: New Directions in Rhetoric and Materiality

Autor Jason Barrett-Foxen Limba Engleză Paperback – 18 apr 2022

Untimely Women recovers the work of three early-twentieth-century working women, none of whom history has understood as feminists or rhetors: cinema icon and memoirist, Mae West; silent film screenwriter and novelist, Anita Loos; and journalist and mega-publisher, Marcet Haldeman-Julius. While contemporary scholarship tends to highlight and recover women who most resemble academic feminists in their uses of propositional rhetoric, Jason Barrett-Fox uses what he terms a medio-materialist historiography to emphasize the different kinds of political and ontological gender-power that emerged from the inscriptional strategies these women employed to navigate and critique male gatekeepers––from movie stars to directors to editors to abusive husbands.

In recasting the work of West, Loos, and Haldeman-Julius in this way, Barrett-Fox reveals the material and ontological ramifications of their forms of invention, particularly their ability to tell trauma in ways that reach beyond their time to raise the consciousness of audiences unavailable to them in their lifetimes. Untimely Women thus accomplishes important historical and rhetorical work that not only brings together feminist historiography, rhetorical materialism, and posthumanism but also redefines what counts as feminist rhetoric.

In recasting the work of West, Loos, and Haldeman-Julius in this way, Barrett-Fox reveals the material and ontological ramifications of their forms of invention, particularly their ability to tell trauma in ways that reach beyond their time to raise the consciousness of audiences unavailable to them in their lifetimes. Untimely Women thus accomplishes important historical and rhetorical work that not only brings together feminist historiography, rhetorical materialism, and posthumanism but also redefines what counts as feminist rhetoric.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (1) | 319.04 lei 38-44 zile | |

| Ohio State University Press – 18 apr 2022 | 319.04 lei 38-44 zile | |

| Hardback (1) | 650.72 lei 38-44 zile | |

| Ohio State University Press – 18 apr 2022 | 650.72 lei 38-44 zile |

Preț: 319.04 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 479

Preț estimativ în valută:

61.05€ • 63.87$ • 50.71£

61.05€ • 63.87$ • 50.71£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 29 martie-04 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780814258286

ISBN-10: 081425828X

Pagini: 216

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Ohio State University Press

Seria New Directions in Rhetoric and Materiality

ISBN-10: 081425828X

Pagini: 216

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Ohio State University Press

Seria New Directions in Rhetoric and Materiality

Recenzii

“Barrett-Fox’s scholarship is impressively interdisciplinary, and his medio-materialist historiography will be of great interest to feminist rhetorical scholars eager to move past the limiting practice of recovering discrete individuals, and to move past recovery more generally.” —Sarah Hallenbeck, author of Claiming the Bicycle: Women, Rhetoric, and Technology in Nineteenth-Century America

Notă biografică

Jason Barrett-Fox is Associate Professor of English and Director of Composition at Weber State University.

Extras

In Pink-Slipped: What Happened to Women in the Silent Film Industries? feminist historian Jane M. Gaines reminds us that very few women in silent film made it on to the historical record—for reasons of taste, capacity, or constraint—and, most troublingly, because historians “implicitly prioritized the study of women ‘approved’ or preferred by feminism’” (116). More than an oversight of historical sensibility, it turns out, such systematic exclusions tend to define the historical record rather than prove its exception. Diving in, Gaines extrapolates a troubling ontological resonance from this seemingly innocuous lacuna, arguing that “for all intents and purposes there were ‘no women’” (116; emphasis mine). Gaines’s deployment of the existential verb suggests that to be disappeared in this fashion hinges on a prior ontological contingency conferred on women. “We count not one but three disappearances,” she explains, “first from the limelight and second from historical records, the second a function of the first” (18). Finally is the third and most worrying erasure, which is “effectively a disappearance in a movement when they might have been discovered and therefore the most difficult for another generation to fathom (18). Women’s erasure from the historical record feeds and is fed by a self-perpetuating and epicyclic ontological obliteration that demands interruption.

Despite history’s failure to recognize them, we know women not only existed but thrived in the silent film industries, working in far greater proportions—and in more leadership roles—than they did in the studio system only decades later, directing, writing, producing, and distributing films. Industry women inscribed their (own) stories outside the lines of suffragist feminism, creating what this book identifies as an incipient and powerful albeit heterogenous feminism of their own, which conveyed in various ways their struggles with gender-power but tended to demure regarding the constellation of issues around women’s voting rights.

Some of these women, silent film scenarist Anita Loos, for example, shoulder part of the blame for their problematic relation with history. When asked during a 1970s silent film retrospective for her take on women’s liberation, Loos decried the women who “keep getting up on soapboxes and proclaiming that women are brighter than men” (Hutchinson par. 1), not because she disagreed with their message but because “it should be kept quiet or it ruins the whole racket” (par. 1). Untimely Women tackles the question of how to approach these long-silenced working women, rhetors and writers who eschewed the feminist zeitgeist or were unintelligible to it. It also seeks to reconfigure historiographical paradigms linked to accepted definitions of women’s agency in the early twentieth century, suggesting that liberal humanism might do more harm than good to women’s rhetorical history.

As a start, we should recognize for this project that all histories, stories of what was, rest (explicitly or not) on some theory of being, some sense of what is, which demands unpacking, perhaps especially if the subjects under investigation are women and their inroads into historical recovery are inscriptional. To put it simply, part of the work of this book comes in using media’s materiality to shore up the relationship between ontology and history, particularly along the lines of expanding what feminism could mean at the beginning of the twentieth century...

In unearthing the oft-obscured relationships between women’s being and doing, this book suggests an approach that relies on women’s uses of the materiality of inscription, which ties their personal and political struggles to the concrete conditions of being, conditions which have been all too often overlooked or downplayed in historical thinking, yet which underscore all of it. In short, this project refuses to contextualize women’s inscription as merely a facet of their humanist individualism. Rather, inscription, not humanist identity, becomes the primary road to being. Ronald E. Day, for instance, urges historians to begin considering “ontology as inscriptionality” (21; emphasis mine) or, at the very least, inscriptionality as a particular, onto-material threshold leading to the dark alleyways of being behind which most of women’s rhetorical history never unfolded.

Despite history’s failure to recognize them, we know women not only existed but thrived in the silent film industries, working in far greater proportions—and in more leadership roles—than they did in the studio system only decades later, directing, writing, producing, and distributing films. Industry women inscribed their (own) stories outside the lines of suffragist feminism, creating what this book identifies as an incipient and powerful albeit heterogenous feminism of their own, which conveyed in various ways their struggles with gender-power but tended to demure regarding the constellation of issues around women’s voting rights.

Some of these women, silent film scenarist Anita Loos, for example, shoulder part of the blame for their problematic relation with history. When asked during a 1970s silent film retrospective for her take on women’s liberation, Loos decried the women who “keep getting up on soapboxes and proclaiming that women are brighter than men” (Hutchinson par. 1), not because she disagreed with their message but because “it should be kept quiet or it ruins the whole racket” (par. 1). Untimely Women tackles the question of how to approach these long-silenced working women, rhetors and writers who eschewed the feminist zeitgeist or were unintelligible to it. It also seeks to reconfigure historiographical paradigms linked to accepted definitions of women’s agency in the early twentieth century, suggesting that liberal humanism might do more harm than good to women’s rhetorical history.

As a start, we should recognize for this project that all histories, stories of what was, rest (explicitly or not) on some theory of being, some sense of what is, which demands unpacking, perhaps especially if the subjects under investigation are women and their inroads into historical recovery are inscriptional. To put it simply, part of the work of this book comes in using media’s materiality to shore up the relationship between ontology and history, particularly along the lines of expanding what feminism could mean at the beginning of the twentieth century...

In unearthing the oft-obscured relationships between women’s being and doing, this book suggests an approach that relies on women’s uses of the materiality of inscription, which ties their personal and political struggles to the concrete conditions of being, conditions which have been all too often overlooked or downplayed in historical thinking, yet which underscore all of it. In short, this project refuses to contextualize women’s inscription as merely a facet of their humanist individualism. Rather, inscription, not humanist identity, becomes the primary road to being. Ronald E. Day, for instance, urges historians to begin considering “ontology as inscriptionality” (21; emphasis mine) or, at the very least, inscriptionality as a particular, onto-material threshold leading to the dark alleyways of being behind which most of women’s rhetorical history never unfolded.

Cuprins

Introduction Future Pasts: Women, Rhetoric, Out of Time Chapter 1 From Oblivion to Eloquence: Repopulating and Refiguring Feminist Rhetorical History Chapter 2 Reinventing the Rules: Anita Loos’s Diffractive Historiography Chapter 3 Following the Forces: Mae West’s Transductive Historiography Chapter 4 Reassembling the Socialist: Marcet Haldeman-Julius’s Metonymic-Archival Historiography Conclusion No More Untellable Stories: Some Prospects for Medio-Materialist Historiography Works Cited Index

Descriere

Recovers feminist rhetors not known for being feminist in their time to offer a more capacious approach to feminist historiography and our definition of feminist rhetoric.