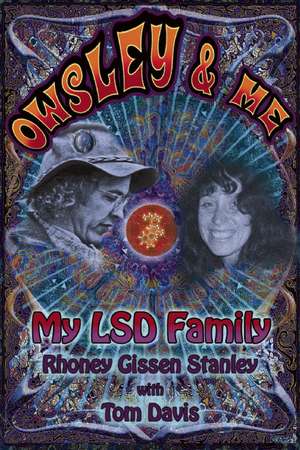

Owsley and Me

Autor Rhoney Gissen Stanleyen Limba Engleză Paperback – 15 apr 2013

Owsley and Me is a love story set against the background of the Psychedelic Revolution of the '60s. Owsley "Bear" Stanley met her in Berkeley in 1965, when LSD was still legal and he was the world's largest producer and distributor of LSD. Rhoney found herself working in an LSD laboratory, and the third corner in a love triangle. We all know the stories from the '60s—but never from the point of view of a woman finding her way through twisted trails of love, jealousy, and paranoia, all the while personally connecting to the most iconic events and people of her time.

Bear supported the Grateful Dead in their early years and gave away as much LSD as he sold—millions of hits. He designed and engineered the infamous Wall of Sound system of the early '70s, just before he began his two years in prison, with Rhoney raising their infant son. He died one year ago, but the era he helped create is now being rediscovered by a new generation interested in the meaning of it all.

Today Rhoney Stanley is a practicing holistic orthodontist in Woodstock, New York. This is her first book.

Tom Davis was an Emmy Award–winning American writer and comedian. He is best known for being one of the original writers for Saturday Night Live and for his former partnership with Al Franken, as half of the comedy duo "Franken & Davis." His memoir Thirty-Nine Years of Short-Term Memory Loss: The Early Days of SNL from Someone Who Was There was published in 2010 by Grove Press.

Bear supported the Grateful Dead in their early years and gave away as much LSD as he sold—millions of hits. He designed and engineered the infamous Wall of Sound system of the early '70s, just before he began his two years in prison, with Rhoney raising their infant son. He died one year ago, but the era he helped create is now being rediscovered by a new generation interested in the meaning of it all.

Today Rhoney Stanley is a practicing holistic orthodontist in Woodstock, New York. This is her first book.

Tom Davis was an Emmy Award–winning American writer and comedian. He is best known for being one of the original writers for Saturday Night Live and for his former partnership with Al Franken, as half of the comedy duo "Franken & Davis." His memoir Thirty-Nine Years of Short-Term Memory Loss: The Early Days of SNL from Someone Who Was There was published in 2010 by Grove Press.

Preț: 108.44 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 163

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.75€ • 21.66$ • 17.17£

20.75€ • 21.66$ • 17.17£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 14-28 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780983358930

ISBN-10: 0983358931

Pagini: 271

Ilustrații: black & white illustrations, black & white line drawings

Dimensiuni: 140 x 213 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.41 kg

Editura: Monkfish Book Publishing

ISBN-10: 0983358931

Pagini: 271

Ilustrații: black & white illustrations, black & white line drawings

Dimensiuni: 140 x 213 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.41 kg

Editura: Monkfish Book Publishing

Recenzii

“Owsley was a key 1960s figure, who some would say "turned on" a generation more so than even Tim Leary, but his own life has long been shrouded in mystery. Here's a firsthand recollection, as "intimate" as is likely to be penned…Here are firsthand backstage accounts of the Monterey Pop Festival, Woodstock, Altamont, and much more … with various Beatles, Stones, San Francisco musicians, of course, and other famed counterculture figures popping in and out.”--Huffington Post

“OWSLEY AND ME is totally geared toward people who have an interest in the music of the time, but also one of the most influential characters of all of drug culture. Think of it as the real BREAKING BAD, just with more peace and love, and a whole lot less guns and dead bodies.”--Bookgasm

“Famous people—Timothy Leary, Jerry Garcia, Ravi Shankar, Jimi Hendrix, Ken Kesey—wander in and out of the story, which delivers a vivid, behind-the-scenes look at the 1960s counterculture. A nostalgia trip for many, to be sure, but also an involving love story that chronicles the sometimes turbulent relationship between Rhoney and Owsley.”--Booklist

Vanity Fair – April issue “Hot Type”

“My LSD Family is an oddly sweet-hearted and heartwarming tome, while also bringing back enough memories to hopefully fuel many memories long forgotten on others’ parts.”--Woodstock Times

"Stanley isn't preaching about redemption, salvation, or crawling out of the pits of drug abuse. She's taking us on a tour of her youth and, fortunately for us, the sights and sounds are colorful and vividly described. If you weren't there yourself, after reading this memoir, odds are, you'll wish you had been."-Blogcritics

"In this wild memoir of life with the media-crowned "Acid King," she (Gissen Stanley) captures the perfectionist genius who also transformed audio technology, created jewelry, advocated a carnivorous diet and studied to be a ballet dancer."--High Times Magazine

"Stanley's memoir is an impressionistic kaleidoscope of the tumultuous times that informed the birth of the Haight and the genesis of the Dead, and her reminiscences help us better understand the complex currents that made that era so iconic, powerful, and still misunderstood."--Grateful Dead Archive

"Owsley and Me: My LSD Family” is a heartfelt memoir of the author’s college years and her love affair with Owsley “Bear” Stanley, who was the pre-eminent producer of LSD in the United States in the 1960s."--Poughkeepsie Journal

“OWSLEY AND ME is totally geared toward people who have an interest in the music of the time, but also one of the most influential characters of all of drug culture. Think of it as the real BREAKING BAD, just with more peace and love, and a whole lot less guns and dead bodies.”--Bookgasm

“Famous people—Timothy Leary, Jerry Garcia, Ravi Shankar, Jimi Hendrix, Ken Kesey—wander in and out of the story, which delivers a vivid, behind-the-scenes look at the 1960s counterculture. A nostalgia trip for many, to be sure, but also an involving love story that chronicles the sometimes turbulent relationship between Rhoney and Owsley.”--Booklist

Vanity Fair – April issue “Hot Type”

“My LSD Family is an oddly sweet-hearted and heartwarming tome, while also bringing back enough memories to hopefully fuel many memories long forgotten on others’ parts.”--Woodstock Times

"Stanley isn't preaching about redemption, salvation, or crawling out of the pits of drug abuse. She's taking us on a tour of her youth and, fortunately for us, the sights and sounds are colorful and vividly described. If you weren't there yourself, after reading this memoir, odds are, you'll wish you had been."-Blogcritics

"In this wild memoir of life with the media-crowned "Acid King," she (Gissen Stanley) captures the perfectionist genius who also transformed audio technology, created jewelry, advocated a carnivorous diet and studied to be a ballet dancer."--High Times Magazine

"Stanley's memoir is an impressionistic kaleidoscope of the tumultuous times that informed the birth of the Haight and the genesis of the Dead, and her reminiscences help us better understand the complex currents that made that era so iconic, powerful, and still misunderstood."--Grateful Dead Archive

"Owsley and Me: My LSD Family” is a heartfelt memoir of the author’s college years and her love affair with Owsley “Bear” Stanley, who was the pre-eminent producer of LSD in the United States in the 1960s."--Poughkeepsie Journal

Notă biografică

Rhoney Stanley lived & worked side by side with Owsley Stanley, one of the pioneers of the psychedelic revolution of the sixties. During their time together, he produced 1.25 million doses of LSD. Together, they raised a son, Starfinder. She is a Columbia University graduate.

Tom Davis was an Emmy Award-winning American writer and comedian. He is best known for being one of the original writers for Saturday Night Live and for his former partnership with Al Franken, as half of the comedy duo "Franken & Davis." His memoir, "Thirty-Nine Years of Short-Term Memory Loss: The Early Days of SNL from Someone Who Was There" was published in 2010 by Grove.

Brief Bio of “Owsley”

Owsley Stanley (better known as “Owsley” or “Bear” to his friends and family) played a key role during the’ psychedelic revolution’ of the sixties. He was the first person to mass manufacture LSD and is reputed to have produced more than 1.25 million doses between the years 1965 to 1967. In 1965 Owsley became the key supplier of LSD to Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters. He was later featured in Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. He also provided LSD to the Beatles during the filming of Magical Mystery Tour.

In 1966 during the Acid tests Owsley met the members of the Grateful Dead. He became their first soundman as well as financier. Along with his close friend Bob Thomas, he designed the Lightning Bolt Skull Logo often referred to by fans as the’ Steal Your Face’ which predated the album of the same name by 8 years. Stanley began a long- term practice of recording the Dead while they rehearsed and performed. Stanley also made numerous live recordings of other leading 1960s and 1970s artists appearing in San Francisco, including Quicksilver Messenger Service, Jefferson Airplane, early Jefferson Starship, Janis Joplin, Big Brother and the Holding Company, Taj Mahal, Santana, Miles Davis, Jimi Hendrix, Johnny Cash, Blue Cheer (a band that took its name from the nickname of Stanley's LSD), and many others. While many Owsley recordings have been released, many more remain unissued.

Owsley was born (1935) into a prominent political family from Kentucky. His father was a government attorney. His grandfather, A. Owsley Stanley, a member of the United States Senate after serving as Governor of Kentucky and in the U.S. House of Representatives, campaigned against alcohol Prohibition. Owsley studied engineering at the University of Virginia before dropping out in 1956.He enlisted in the U.S. Air Force and served for eighteen months before being discharged in 1958. Later, inspired by a 1958 performance of the Bolshoi Ballet, he began studying ballet in Los Angeles, supporting himself for a time as a professional dancer. In 1963, he enrolled at the University of California, Berkeley where he became involved in the psychoactive drug scene. He dropped out after a semester, took a technical job at KGO-TV, and began producing LSD in a small lab located in the bathroom of a house near campus. His makeshift laboratory was raided by police on February 21, 1965. He beat the charges and successfully sued for the return of his equipment. The police were looking for methamphetamine but found only LSD, which was not illegal at the time.

In 1970, 19 members of the Grateful Dead and crew were busted at a French Quarter hotel after returning from a concert at "The Warehouse" in New Orleans, Louisiana for a combination of drugs.. Everybody in the band, except Pigpen and Tom Constanten, was included in the bust including s a man listed as Owsley Stanley, 35, of Alexandria, Virginia, a technician for the band, booked with illegal possession of narcotics, dangerous non-narcotics, LSD, and barbiturates. Ultimately Owsley was confined to Federal prison from 1970 to 1972, after a Federal judge intervened by revoking his release from the 1967 case. Stanley took advantage of the opportunity there to learn metalwork and jewelry-making.

Owsley died after an automobile accident in Australia on March 12, 2011. The statement released on behalf of Stanley's family said the car crash occurred near his home, on a rural stretch of highway near Mareeba, Queensland. He is survived by his wife Sheila, four children, eight grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren.

Tom Davis was an Emmy Award-winning American writer and comedian. He is best known for being one of the original writers for Saturday Night Live and for his former partnership with Al Franken, as half of the comedy duo "Franken & Davis." His memoir, "Thirty-Nine Years of Short-Term Memory Loss: The Early Days of SNL from Someone Who Was There" was published in 2010 by Grove.

Brief Bio of “Owsley”

Owsley Stanley (better known as “Owsley” or “Bear” to his friends and family) played a key role during the’ psychedelic revolution’ of the sixties. He was the first person to mass manufacture LSD and is reputed to have produced more than 1.25 million doses between the years 1965 to 1967. In 1965 Owsley became the key supplier of LSD to Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters. He was later featured in Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. He also provided LSD to the Beatles during the filming of Magical Mystery Tour.

In 1966 during the Acid tests Owsley met the members of the Grateful Dead. He became their first soundman as well as financier. Along with his close friend Bob Thomas, he designed the Lightning Bolt Skull Logo often referred to by fans as the’ Steal Your Face’ which predated the album of the same name by 8 years. Stanley began a long- term practice of recording the Dead while they rehearsed and performed. Stanley also made numerous live recordings of other leading 1960s and 1970s artists appearing in San Francisco, including Quicksilver Messenger Service, Jefferson Airplane, early Jefferson Starship, Janis Joplin, Big Brother and the Holding Company, Taj Mahal, Santana, Miles Davis, Jimi Hendrix, Johnny Cash, Blue Cheer (a band that took its name from the nickname of Stanley's LSD), and many others. While many Owsley recordings have been released, many more remain unissued.

Owsley was born (1935) into a prominent political family from Kentucky. His father was a government attorney. His grandfather, A. Owsley Stanley, a member of the United States Senate after serving as Governor of Kentucky and in the U.S. House of Representatives, campaigned against alcohol Prohibition. Owsley studied engineering at the University of Virginia before dropping out in 1956.He enlisted in the U.S. Air Force and served for eighteen months before being discharged in 1958. Later, inspired by a 1958 performance of the Bolshoi Ballet, he began studying ballet in Los Angeles, supporting himself for a time as a professional dancer. In 1963, he enrolled at the University of California, Berkeley where he became involved in the psychoactive drug scene. He dropped out after a semester, took a technical job at KGO-TV, and began producing LSD in a small lab located in the bathroom of a house near campus. His makeshift laboratory was raided by police on February 21, 1965. He beat the charges and successfully sued for the return of his equipment. The police were looking for methamphetamine but found only LSD, which was not illegal at the time.

In 1970, 19 members of the Grateful Dead and crew were busted at a French Quarter hotel after returning from a concert at "The Warehouse" in New Orleans, Louisiana for a combination of drugs.. Everybody in the band, except Pigpen and Tom Constanten, was included in the bust including s a man listed as Owsley Stanley, 35, of Alexandria, Virginia, a technician for the band, booked with illegal possession of narcotics, dangerous non-narcotics, LSD, and barbiturates. Ultimately Owsley was confined to Federal prison from 1970 to 1972, after a Federal judge intervened by revoking his release from the 1967 case. Stanley took advantage of the opportunity there to learn metalwork and jewelry-making.

Owsley died after an automobile accident in Australia on March 12, 2011. The statement released on behalf of Stanley's family said the car crash occurred near his home, on a rural stretch of highway near Mareeba, Queensland. He is survived by his wife Sheila, four children, eight grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren.

Extras

Robert Hunter Meets Owsleystein

At the Fillmore West, formerly the Carousel Ballroom, my nickname was Electric. I would share my LSD. I loved getting high. I was good at it. I had my freak-out early in the game, but after more than a hundred acid trips, my familiarization changed the experience. I still had hallucinatory visuals, but my free-associative inner thoughts were now the place of transformation. My self got high.

In 1969, on the night of June 7, I gyrated on the dance floor under the strobe light, losing my self in the rhythm section of the Grateful Dead. Then Janis Joplin came on stage and joined Pigpen for “Turn On Your Love Light.”

“Turn on your love light,” I screamed, inaudible in the ocean of amplified music. Onstage Pigpen and Janis reveled in the lyrics and each other. On the floor, everyone danced with abandon. Bear appeared and gravitated to me. We moved in circles around each other, faster and faster.

The song ended, the house lights came on, and hundreds of stoned hippies looked

for each other. We went backstage where Janis was sprawled on a velvet upholstered chair with her legs over the arm rest. The three-gallon stainless steel punch bowl on the table was empty. Wow, I thought. Bear had spiked the Kool-Aid with LSD and it was all gone. No wonder everyone was so stoned.

Janis sprang up from the chair, shook out her bell-bottoms, and angrily approached Bear. “Man,” she roared, “What the fuck did you put in that Kool-Aid?” She pointed her finger at Bear’s face, her voice hoarse from singing. Her bracelets jangled. “My saxophone player is in the hospital. Your fucking Kool-Aid freaked him out. Man, you know these cats are studio musicians. They don’t know from your fuckin’ psychedelic scene.”

Bear was suddenly sober to make sense of this onslaught. “I put the usual in the Kool-Aid. If your sax man can’t handle a little pure LSD, he might not be up to your standard.” Bear was still pissed at Janis for leaving Big Brother. He was convinced that Big Brother had been a better band.

Janis was insulted. “He’s a great sax man, and now he’s in the hospital overdosed on your fuckin’ LSD.”

“What did he do—drink half the bowl?” Bear twittered provocatively.

Janis and Bear argued—two confrontational Capricorns who shared a January

19th birthday. Bear explained with his usual dose, 270 micrograms, drinking a glassful, as most people did, was ideal. Still, how much Kool-Aid is in a punchbowl? Bear would have put his aluminum briefcase down on the table with assorted cookies, paper cups, and the punchbowl. Opening his bountiful man-purse, he would have pulled out a glycine paper bindle of crystalline LSD and added a measure to the punchbowl like a chef adding stock to the soup du jour. As he had on other occasions, he might have stirred the liquid with his finger, then put it in his mouth, testing the taste for the slightly acerbic presence

of lysergic acid.

“With more than a cup, you’d have a sugar meltdown. The insulin release is

worse on your system,” Bear declared. “The dose in a glass of punch is too small to send your sax man to the hospital. Something else must have happened.”

“A lot of people got too stoned,” someone joined in. Bear questioned a few prominent entities backstage and found that Goldfinger had been there before the show. “He must have spiked the Kool-Aid too. What an asshole. He didn’t even check with me.”

Owsley was furious but continued to methodically pack up the equipment. When we were ready to leave, no one was left in the ballroom except Bill Graham standing on the stairway with his arms crossed. Owsley was vexed but silent as we slid past and out the door. The night air was cold and clear. The stars were out and beckoning. The music was still playing in my head. My feet barely touched the ground.

“Let’s go to OJ’s for a steak.”

“Good,” I answered. “I’m hungry, too.”

The street was deserted. Then I heard a moan, a guttural utterance as if an animal were in distress. At first I thought I was hallucinating, but then I heard it again. It seemed to come from below. I saw a naked human form, flesh and hair lying in the gutter. I bent closer and recognized Robert Hunter’s face. He was dirty, distressed, muttering to himself. When Bear walked up, Hunter jumped to his feet.

“Owsleystein!” He grabbed Bear in a headlock.

“Hunter,” I cried, “What are you doing? That’s Bear.”

He acted like he couldn’t hear me and responded, “I will annihilate you, Owsleystein!”

Bear was trying not to struggle with his freaked-out friend.

“The monster you created destroyeth you.” Hunter was bulky and strong, and I pulled at his arm around Bear’s neck, and suddenly he fell to the ground. His eyes were wide and so dilated I couldn’t see their color. Bear got away and quietly walked in the direction of the car. I stood by the stricken poet.

“No, Bear, we can’t leave Hunter like this.”

Bear stopped in his tracks and stared at the sidewalk, his hands clenched at his

sides. “Fuck it! Now we can’t go to Original Joe's. Let’s take Hunter to Goldfinger’s house. I’ll get the car.”

Hunter was speaking in his deep voice of dire predictions, dreaded consequences,

crackups, and wrecks. He was in a time warp, an alternate reality on Market Street. Hunter thought I was sharing his vision, but I had no idea what planet he was on. I knew enough not to drink from an open punch bowl. My own supply had given me the choice of how high I wanted to get. To me Hunter looked like a prehistoric man, a Neanderthal,as he lay down once more in the gutter on Market Street. I couldn’t help staring at his penis.

“Hunter,” I asked, “Where are your clothes?”

He pointed. About thirty feet further up the street were his jeans, white briefs, socks, and boots. Here was the poet who translated Rilke’s poetry, the intellectual who embraced the philosophy of Edmund Husserl, believing that perception alters fact. Boy, was he dusted. I offered him his jeans. “Put on your clothes!”He accepted the pants, then threw them into the street. “Don’t tell me what to do. You are not my mother.”

He was right. I was being judgmental and critical at a time when love was needed. I had fallen back into old behavior patterns from my own fucked-up mother. I had not transformed. Oy vey iz mir.

Bear pulled up in the car. I opened the door to the back seat. “Hunter, come on.

Get in.”

Hunter looked at me without recognition. Bear helped me get Hunter on his feet

but he resisted, pointing his finger at Bear, howling, “Owsleystein.”

“Hunter does not want to come with us. Let’s go.”

“No, Bear. We can’t leave him here.” I stood before the caveman and looked into

his eyes. “Hunter, it’s Rhoney, Rhoney. See, me.” I took his hand and tapped it on my head. “You can’t stay on the street. It’s late. The gig is over. Everyone’s gone.”

His face became the mask of tragedy. “She’s gone,” he moaned, tears welling.

“Hunter, what’s the matter? Is it Christie you’ve lost?” He shook his head yes. He and his gorgeous girlfriend were inseparable. Where was she?

“Don’t worry. We’ll find her. Come with us now. Hunter, please,” I pleaded. “Get

into the car. We’ll look for Christie. I promise. Everything will be okay. Come on, baby. ‘Come on baby, do the locomotion.’” I sung to him in my raspy voice and wiggled my butt like a choo-choo train. My voice soothed him enough to get him into the backseat.

Bear drove in his haphazard fashion through a maze of back streets until we

pulled up in front of Goldfinger’s Victorian flat on Nob Hill. Hunter was crouched down and quiet, but when the engine stopped he wailed, “She always will be in the shadow of my heart. Where, where did she go?”

“Hunter, it’s okay. We’ll find her.”

“Hunter’s a Cancer. He can’t help worrying about his home and family,” observed

Bear. “Let’s dump him on Goldfinger.”

Hunter was a big guy and it was a struggle to get him halfway up the long

stairway to Goldfinger’s front door. I held up Hunter as Bear scrambled to the top and returned with Goldfinger’s girl, Nicki. Goldfinger wasn’t there, but Nicki was cool. The three of us guided Hunter up the remaining climb, his deep voice calling out, “Gone,” as we made it inside.

Nicki said, “She could be at Garcia’s. I’ll call out there.”

Hunter sat on the sofa by the bay window looking out at the Golden Gate Bridge.

He shook his head. “No, no!”

Nicki frisked her long brown hair off her face as she sat before the heavy black

telephone on the table. She concentrated on the matter at hand. The babysitter answered. No, Mountain Girl and Garcia were not home.

“Someone at the Airplane House will know where he is.” Bear sat next to Nicki

and commandeered the phone, but no Goldfinger.

Hunter pointed at Bear. “Owsleystein!” Then his arm fell back and he stared at

the Persian carpet.

“I think he’s better,” Owsley said.

“Hunter,” I asked, “Would you like some water?”

No answer. I went into the kitchen and brought back a glass of water. I handed

Hunter the heavy, ornate glass. He eyed it suspiciously and gave it back. Nicki propped a pillow behind him, and he slumped on the couch. She joined me at the table. Bear rummaged through the refrigerator, looking for food, ruminating on his options, “Rabbit food. Nothing but rabbit food.” He turned to us. “Where is Goldfinger? I hope he just put acid in that Kool-Aid. But with Goldfinger, you never know.” Bear chuckled.

I realized I was getting hungry, too. I found bread, cereal, milk, and bananas.

Comfort food was just fine with me.

“Carbs, nothing but carbs,” Bear commented. “There’s nothing to eat.”

I contradicted him. “There’s a jar of peanut butter.”

“Where?”

“The second shelf on the door.”

Just then Hunter walked in and ranted about the way reality looked to him, “Only

perception gives an object dimension, that the mind creates. I am not your creation. I am not your trip. I control my presentation in time. You only control your perception of me.”

I was still very high myself. I was in that clear mental state when the mind feels like a planet-sized chamber. “Hunter,” I asked, engaging his thought processes, “is it the viewer’s perception of consciousness, not consciousness itself, which is critical?”

Suddenly Hunter looked happy.

“It is not the object but the perception of the object. There are distinctions and there are connections.” I felt as if I finally had done something to help. I smiled too. But just as quickly, Hunter returned to the darkness; his words became incoherent. He dropped to the couch, put his hands over his mouth, and became lachrymose.

Nicki suggested taking Hunter to the hospital, but Bear and I knew that was a bad idea. In hospitals, they put freak-outs on Thorazine.

“Thorazine is the wrong way to go,” Bear said, “but niacinamide—it sometimes

works. I’ve got some here, I think.”

Niacinamide is a B vitamin that has antianxiety effects. In 1956, Abram Hoffer,

one of Bear’s heroes, a Canadian biochemist and MD, had successfully reversed all LSD symptoms by intravenously injecting one gram of niacinamide into subjects high on LSD; however, the government quashed LSD research before the start of clinical trials. Bear went to his aluminum briefcase and produced a bottle of 1,000-microgram pills.

“Works better if injected, but . . .” Bear counted out ten.

Hunter was so weak, I helped him put the pills in his mouth, but

At the Fillmore West, formerly the Carousel Ballroom, my nickname was Electric. I would share my LSD. I loved getting high. I was good at it. I had my freak-out early in the game, but after more than a hundred acid trips, my familiarization changed the experience. I still had hallucinatory visuals, but my free-associative inner thoughts were now the place of transformation. My self got high.

In 1969, on the night of June 7, I gyrated on the dance floor under the strobe light, losing my self in the rhythm section of the Grateful Dead. Then Janis Joplin came on stage and joined Pigpen for “Turn On Your Love Light.”

“Turn on your love light,” I screamed, inaudible in the ocean of amplified music. Onstage Pigpen and Janis reveled in the lyrics and each other. On the floor, everyone danced with abandon. Bear appeared and gravitated to me. We moved in circles around each other, faster and faster.

The song ended, the house lights came on, and hundreds of stoned hippies looked

for each other. We went backstage where Janis was sprawled on a velvet upholstered chair with her legs over the arm rest. The three-gallon stainless steel punch bowl on the table was empty. Wow, I thought. Bear had spiked the Kool-Aid with LSD and it was all gone. No wonder everyone was so stoned.

Janis sprang up from the chair, shook out her bell-bottoms, and angrily approached Bear. “Man,” she roared, “What the fuck did you put in that Kool-Aid?” She pointed her finger at Bear’s face, her voice hoarse from singing. Her bracelets jangled. “My saxophone player is in the hospital. Your fucking Kool-Aid freaked him out. Man, you know these cats are studio musicians. They don’t know from your fuckin’ psychedelic scene.”

Bear was suddenly sober to make sense of this onslaught. “I put the usual in the Kool-Aid. If your sax man can’t handle a little pure LSD, he might not be up to your standard.” Bear was still pissed at Janis for leaving Big Brother. He was convinced that Big Brother had been a better band.

Janis was insulted. “He’s a great sax man, and now he’s in the hospital overdosed on your fuckin’ LSD.”

“What did he do—drink half the bowl?” Bear twittered provocatively.

Janis and Bear argued—two confrontational Capricorns who shared a January

19th birthday. Bear explained with his usual dose, 270 micrograms, drinking a glassful, as most people did, was ideal. Still, how much Kool-Aid is in a punchbowl? Bear would have put his aluminum briefcase down on the table with assorted cookies, paper cups, and the punchbowl. Opening his bountiful man-purse, he would have pulled out a glycine paper bindle of crystalline LSD and added a measure to the punchbowl like a chef adding stock to the soup du jour. As he had on other occasions, he might have stirred the liquid with his finger, then put it in his mouth, testing the taste for the slightly acerbic presence

of lysergic acid.

“With more than a cup, you’d have a sugar meltdown. The insulin release is

worse on your system,” Bear declared. “The dose in a glass of punch is too small to send your sax man to the hospital. Something else must have happened.”

“A lot of people got too stoned,” someone joined in. Bear questioned a few prominent entities backstage and found that Goldfinger had been there before the show. “He must have spiked the Kool-Aid too. What an asshole. He didn’t even check with me.”

Owsley was furious but continued to methodically pack up the equipment. When we were ready to leave, no one was left in the ballroom except Bill Graham standing on the stairway with his arms crossed. Owsley was vexed but silent as we slid past and out the door. The night air was cold and clear. The stars were out and beckoning. The music was still playing in my head. My feet barely touched the ground.

“Let’s go to OJ’s for a steak.”

“Good,” I answered. “I’m hungry, too.”

The street was deserted. Then I heard a moan, a guttural utterance as if an animal were in distress. At first I thought I was hallucinating, but then I heard it again. It seemed to come from below. I saw a naked human form, flesh and hair lying in the gutter. I bent closer and recognized Robert Hunter’s face. He was dirty, distressed, muttering to himself. When Bear walked up, Hunter jumped to his feet.

“Owsleystein!” He grabbed Bear in a headlock.

“Hunter,” I cried, “What are you doing? That’s Bear.”

He acted like he couldn’t hear me and responded, “I will annihilate you, Owsleystein!”

Bear was trying not to struggle with his freaked-out friend.

“The monster you created destroyeth you.” Hunter was bulky and strong, and I pulled at his arm around Bear’s neck, and suddenly he fell to the ground. His eyes were wide and so dilated I couldn’t see their color. Bear got away and quietly walked in the direction of the car. I stood by the stricken poet.

“No, Bear, we can’t leave Hunter like this.”

Bear stopped in his tracks and stared at the sidewalk, his hands clenched at his

sides. “Fuck it! Now we can’t go to Original Joe's. Let’s take Hunter to Goldfinger’s house. I’ll get the car.”

Hunter was speaking in his deep voice of dire predictions, dreaded consequences,

crackups, and wrecks. He was in a time warp, an alternate reality on Market Street. Hunter thought I was sharing his vision, but I had no idea what planet he was on. I knew enough not to drink from an open punch bowl. My own supply had given me the choice of how high I wanted to get. To me Hunter looked like a prehistoric man, a Neanderthal,as he lay down once more in the gutter on Market Street. I couldn’t help staring at his penis.

“Hunter,” I asked, “Where are your clothes?”

He pointed. About thirty feet further up the street were his jeans, white briefs, socks, and boots. Here was the poet who translated Rilke’s poetry, the intellectual who embraced the philosophy of Edmund Husserl, believing that perception alters fact. Boy, was he dusted. I offered him his jeans. “Put on your clothes!”He accepted the pants, then threw them into the street. “Don’t tell me what to do. You are not my mother.”

He was right. I was being judgmental and critical at a time when love was needed. I had fallen back into old behavior patterns from my own fucked-up mother. I had not transformed. Oy vey iz mir.

Bear pulled up in the car. I opened the door to the back seat. “Hunter, come on.

Get in.”

Hunter looked at me without recognition. Bear helped me get Hunter on his feet

but he resisted, pointing his finger at Bear, howling, “Owsleystein.”

“Hunter does not want to come with us. Let’s go.”

“No, Bear. We can’t leave him here.” I stood before the caveman and looked into

his eyes. “Hunter, it’s Rhoney, Rhoney. See, me.” I took his hand and tapped it on my head. “You can’t stay on the street. It’s late. The gig is over. Everyone’s gone.”

His face became the mask of tragedy. “She’s gone,” he moaned, tears welling.

“Hunter, what’s the matter? Is it Christie you’ve lost?” He shook his head yes. He and his gorgeous girlfriend were inseparable. Where was she?

“Don’t worry. We’ll find her. Come with us now. Hunter, please,” I pleaded. “Get

into the car. We’ll look for Christie. I promise. Everything will be okay. Come on, baby. ‘Come on baby, do the locomotion.’” I sung to him in my raspy voice and wiggled my butt like a choo-choo train. My voice soothed him enough to get him into the backseat.

Bear drove in his haphazard fashion through a maze of back streets until we

pulled up in front of Goldfinger’s Victorian flat on Nob Hill. Hunter was crouched down and quiet, but when the engine stopped he wailed, “She always will be in the shadow of my heart. Where, where did she go?”

“Hunter, it’s okay. We’ll find her.”

“Hunter’s a Cancer. He can’t help worrying about his home and family,” observed

Bear. “Let’s dump him on Goldfinger.”

Hunter was a big guy and it was a struggle to get him halfway up the long

stairway to Goldfinger’s front door. I held up Hunter as Bear scrambled to the top and returned with Goldfinger’s girl, Nicki. Goldfinger wasn’t there, but Nicki was cool. The three of us guided Hunter up the remaining climb, his deep voice calling out, “Gone,” as we made it inside.

Nicki said, “She could be at Garcia’s. I’ll call out there.”

Hunter sat on the sofa by the bay window looking out at the Golden Gate Bridge.

He shook his head. “No, no!”

Nicki frisked her long brown hair off her face as she sat before the heavy black

telephone on the table. She concentrated on the matter at hand. The babysitter answered. No, Mountain Girl and Garcia were not home.

“Someone at the Airplane House will know where he is.” Bear sat next to Nicki

and commandeered the phone, but no Goldfinger.

Hunter pointed at Bear. “Owsleystein!” Then his arm fell back and he stared at

the Persian carpet.

“I think he’s better,” Owsley said.

“Hunter,” I asked, “Would you like some water?”

No answer. I went into the kitchen and brought back a glass of water. I handed

Hunter the heavy, ornate glass. He eyed it suspiciously and gave it back. Nicki propped a pillow behind him, and he slumped on the couch. She joined me at the table. Bear rummaged through the refrigerator, looking for food, ruminating on his options, “Rabbit food. Nothing but rabbit food.” He turned to us. “Where is Goldfinger? I hope he just put acid in that Kool-Aid. But with Goldfinger, you never know.” Bear chuckled.

I realized I was getting hungry, too. I found bread, cereal, milk, and bananas.

Comfort food was just fine with me.

“Carbs, nothing but carbs,” Bear commented. “There’s nothing to eat.”

I contradicted him. “There’s a jar of peanut butter.”

“Where?”

“The second shelf on the door.”

Just then Hunter walked in and ranted about the way reality looked to him, “Only

perception gives an object dimension, that the mind creates. I am not your creation. I am not your trip. I control my presentation in time. You only control your perception of me.”

I was still very high myself. I was in that clear mental state when the mind feels like a planet-sized chamber. “Hunter,” I asked, engaging his thought processes, “is it the viewer’s perception of consciousness, not consciousness itself, which is critical?”

Suddenly Hunter looked happy.

“It is not the object but the perception of the object. There are distinctions and there are connections.” I felt as if I finally had done something to help. I smiled too. But just as quickly, Hunter returned to the darkness; his words became incoherent. He dropped to the couch, put his hands over his mouth, and became lachrymose.

Nicki suggested taking Hunter to the hospital, but Bear and I knew that was a bad idea. In hospitals, they put freak-outs on Thorazine.

“Thorazine is the wrong way to go,” Bear said, “but niacinamide—it sometimes

works. I’ve got some here, I think.”

Niacinamide is a B vitamin that has antianxiety effects. In 1956, Abram Hoffer,

one of Bear’s heroes, a Canadian biochemist and MD, had successfully reversed all LSD symptoms by intravenously injecting one gram of niacinamide into subjects high on LSD; however, the government quashed LSD research before the start of clinical trials. Bear went to his aluminum briefcase and produced a bottle of 1,000-microgram pills.

“Works better if injected, but . . .” Bear counted out ten.

Hunter was so weak, I helped him put the pills in his mouth, but

Descriere

Owsley and Me is an insider's account of sixties counterculture, told by the partner of Owsley "Bear" Stanley.