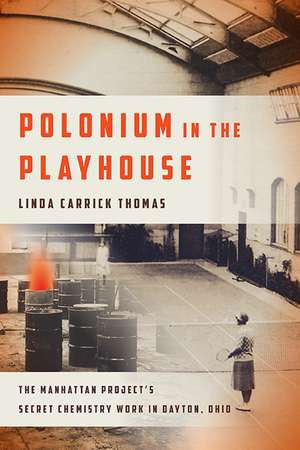

Polonium in the Playhouse: The Manhattan Project’s Secret Chemistry Work in Dayton, Ohio

Autor Linda Carrick Thomasen Limba Engleză Paperback – 21 mai 2017

At the height of the race to build an atomic bomb, an indoor tennis court in one of the Midwest’s most affluent residential neighborhoods became a secret Manhattan Project laboratory. Polonium in the Playhouse: The Manhattan Project's Secret Chemistry Work in Dayton, Ohio presents the intriguing story of how this most unlikely site in Dayton, Ohio, became one of the most classified portions of the Manhattan Project.

Seized by the War Department in 1944 for the bomb project, the Runnymede Playhouse was transformed into a polonium processing facility, providing a critical radioactive ingredient for the bomb initiator—the mechanism that triggered a chain reaction. With the help of a Soviet spy working undercover at the site, it was also key to the Soviet Union’s atomic bomb program.

The work was directed by industrial chemist Charles Allen Thomas who had been chosen by J. Robert Oppenheimer and General Leslie Groves to coordinate Manhattan Project chemistry and metallurgy. As one of the nation’s first science administrators, Thomas was responsible for choreographing the plutonium work at Los Alamos and the Project’s key laboratories. The elegant glass-roofed building belonged to his wife’s family.

Weaving Manhattan Project history with the life and work of the scientist, industrial leader and singing-showman Thomas, Polonium in the Playhouse offers a fascinating look at the vast and complicated program that changed world history and introduces the men and women who raced against time to build the initiator for the bomb.

Seized by the War Department in 1944 for the bomb project, the Runnymede Playhouse was transformed into a polonium processing facility, providing a critical radioactive ingredient for the bomb initiator—the mechanism that triggered a chain reaction. With the help of a Soviet spy working undercover at the site, it was also key to the Soviet Union’s atomic bomb program.

The work was directed by industrial chemist Charles Allen Thomas who had been chosen by J. Robert Oppenheimer and General Leslie Groves to coordinate Manhattan Project chemistry and metallurgy. As one of the nation’s first science administrators, Thomas was responsible for choreographing the plutonium work at Los Alamos and the Project’s key laboratories. The elegant glass-roofed building belonged to his wife’s family.

Weaving Manhattan Project history with the life and work of the scientist, industrial leader and singing-showman Thomas, Polonium in the Playhouse offers a fascinating look at the vast and complicated program that changed world history and introduces the men and women who raced against time to build the initiator for the bomb.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (1) | 139.32 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| Ohio State University Press – 21 mai 2017 | 139.32 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| Hardback (1) | 218.90 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| Ohio State University Press – 21 mai 2017 | 218.90 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 139.32 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 209

Preț estimativ în valută:

26.66€ • 28.51$ • 22.23£

26.66€ • 28.51$ • 22.23£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 28 martie-11 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780814254042

ISBN-10: 0814254047

Pagini: 272

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.4 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Trillium

ISBN-10: 0814254047

Pagini: 272

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.4 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Trillium

Recenzii

“It’s not easy to write a book that will fascinate history buffs, science enthusiasts, and the merely curious alike, but Linda Carrier Thomas succeeds admirably in Polonium in the Playhouse.” —Susan Waggoner, Foreword Reviews

“In her highly readable Polonium in the Playhouse, Linda Carrick Thomas sheds light on a deliciously eccentric piece of WWII home-front history.” —Susan Waggoner, Foreword Reviews

"Polonium in the Playhouse is an engagingly written volume that deserves a place on the bookshelf of any serious student of the Manhattan Project.” —Cameron Reed, author of The History and Science of the Manhattan Project

“With many lively firsthand accounts, Polonium in the Playhouse appeals to a broad audience and makes an important contribution to Manhattan Project history. Highly recommended!” —Cynthia C. Kelly, President, Atomic Heritage Foundation

“Linda Thomas has filled an important gap in the historiography of the atomic bomb by describing the highly secret polonium project in Dayton, Ohio. The man in charge, Charles A. Thomas, is one of many unsung heroes of the Manhattan Project and has finally gotten the recognition he deserves.” —Robert S. Norris, author of Racing for the Bomb: General Leslie R. Groves, the Manhattan Project’s Indispensable Man

Notă biografică

Linda Carrick Thomas is a freelance writer and editor. A former newspaper journalist and assistant director in higher education communications, she was raised in Boston and San Diego and lives in Indiana. She is the granddaughter of Manhattan Project administrator and industrial chemist Charles Allen Thomas.

Extras

Setting the Scene

During the spring of 1944, delivery trucks began rolling in and out of the affluent Dayton neighborhood of Oakwood, navigating winding streets and passing leafy estates such as that of aviation pioneer Orville Wright. The trucks came and went at all hours from the Talbott Playhouse at 715 Runnymede Road, a prominent family’s indoor tennis court and recreation facility. They drew the attention of neighbors who knew not to ask too much. It was wartime and the nation was involved in defense activity.

Residents were told the trucks were going to and from a government film processing facility. They were, in fact, couriers transporting one of the world’s most dangerous elements, polonium, which was purified in Oakwood and then shipped to Los Alamos for use in the trigger of the plutonium bomb first tested at the Trinity site in the New Mexico desert and conclusively detonated over Nagasaki on August 9, 1945. The work, known as the Dayton Project, was the most closely guarded portion of the Manhattan Project because its product—refined polonium for the trigger—was so essential to the bomb. Its history is not widely known.

The work in Dayton was hidden in plain sight. The main Manhattan Project sites were built in remote areas—Site Y (Los Alamos) in the New Mexico desert; Clinton (now known as Oak Ridge) in the hills of Tennessee; and Hanford on the plains of Washington. The work in Dayton, by comparison, took place in the middle of a busy metropolitan area. Laboratories were located downtown in a former elementary school and on an estate in a residential neighborhood. Industrial chemist Charles Allen Thomas, the MIT-educated director of Dayton’s Monsanto Central Research, directed this work. As coordinator of chemistry and metallurgy for the Manhattan Project, he also oversaw the plutonium research and development in laboratories at Los Alamos; the University of California, Berkeley; the University of Chicago’s Metallurgical lab (Met Lab); and at Iowa State College.

The highly classified nature of the work in Dayton may well have obscured its place in history. Shortly after the war, Manhattan Project director General Leslie Groves acknowledged this in a letter to Monsanto chairman Edgar Queeny, stating that information on the Dayton Project must remain publicly unreleased. “A detailed description of your efforts must still remain undisclosed because of security considerations,” Groves wrote.1 The work was so essential and buried so deep within the overall project that Dayton Project personnel could not obtain supplies through the usual priority rating given Manhattan Project sites, lest the work be associated with the bomb project. “It was considered very secret. It was part of the weapon (but) we gave very little indication to anybody we needed it,” recalled Major General Kenneth Nichols, who served as Manhattan District Engineer, overseeing the uranium and plutonium production at Oak Ridge and Hanford.2 Records for the Dayton Project remain among the most highly classified of Manhattan Project documents and have not been readily available to those exploring the vast map of the Manhattan Project. It is as if the Dayton Project never existed. And yet it did.

During the spring of 1944, delivery trucks began rolling in and out of the affluent Dayton neighborhood of Oakwood, navigating winding streets and passing leafy estates such as that of aviation pioneer Orville Wright. The trucks came and went at all hours from the Talbott Playhouse at 715 Runnymede Road, a prominent family’s indoor tennis court and recreation facility. They drew the attention of neighbors who knew not to ask too much. It was wartime and the nation was involved in defense activity.

Residents were told the trucks were going to and from a government film processing facility. They were, in fact, couriers transporting one of the world’s most dangerous elements, polonium, which was purified in Oakwood and then shipped to Los Alamos for use in the trigger of the plutonium bomb first tested at the Trinity site in the New Mexico desert and conclusively detonated over Nagasaki on August 9, 1945. The work, known as the Dayton Project, was the most closely guarded portion of the Manhattan Project because its product—refined polonium for the trigger—was so essential to the bomb. Its history is not widely known.

The work in Dayton was hidden in plain sight. The main Manhattan Project sites were built in remote areas—Site Y (Los Alamos) in the New Mexico desert; Clinton (now known as Oak Ridge) in the hills of Tennessee; and Hanford on the plains of Washington. The work in Dayton, by comparison, took place in the middle of a busy metropolitan area. Laboratories were located downtown in a former elementary school and on an estate in a residential neighborhood. Industrial chemist Charles Allen Thomas, the MIT-educated director of Dayton’s Monsanto Central Research, directed this work. As coordinator of chemistry and metallurgy for the Manhattan Project, he also oversaw the plutonium research and development in laboratories at Los Alamos; the University of California, Berkeley; the University of Chicago’s Metallurgical lab (Met Lab); and at Iowa State College.

The highly classified nature of the work in Dayton may well have obscured its place in history. Shortly after the war, Manhattan Project director General Leslie Groves acknowledged this in a letter to Monsanto chairman Edgar Queeny, stating that information on the Dayton Project must remain publicly unreleased. “A detailed description of your efforts must still remain undisclosed because of security considerations,” Groves wrote.1 The work was so essential and buried so deep within the overall project that Dayton Project personnel could not obtain supplies through the usual priority rating given Manhattan Project sites, lest the work be associated with the bomb project. “It was considered very secret. It was part of the weapon (but) we gave very little indication to anybody we needed it,” recalled Major General Kenneth Nichols, who served as Manhattan District Engineer, overseeing the uranium and plutonium production at Oak Ridge and Hanford.2 Records for the Dayton Project remain among the most highly classified of Manhattan Project documents and have not been readily available to those exploring the vast map of the Manhattan Project. It is as if the Dayton Project never existed. And yet it did.