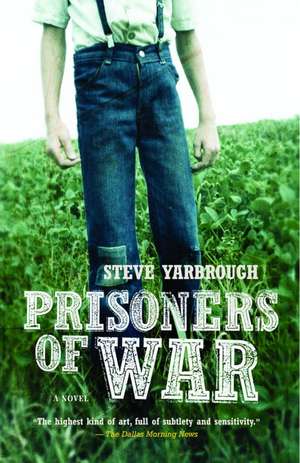

Prisoners of War: Vintage Contemporaries

Autor Steve Yarbroughen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2004

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

PEN/Faulkner Award (2005)

Din seria Vintage Contemporaries

-

Preț: 109.95 lei

Preț: 109.95 lei -

Preț: 101.80 lei

Preț: 101.80 lei -

Preț: 125.21 lei

Preț: 125.21 lei -

Preț: 107.46 lei

Preț: 107.46 lei -

Preț: 105.38 lei

Preț: 105.38 lei -

Preț: 119.87 lei

Preț: 119.87 lei -

Preț: 111.51 lei

Preț: 111.51 lei -

Preț: 96.11 lei

Preț: 96.11 lei -

Preț: 99.75 lei

Preț: 99.75 lei -

Preț: 96.52 lei

Preț: 96.52 lei -

Preț: 111.92 lei

Preț: 111.92 lei -

Preț: 117.87 lei

Preț: 117.87 lei -

Preț: 95.92 lei

Preț: 95.92 lei -

Preț: 113.56 lei

Preț: 113.56 lei -

Preț: 100.35 lei

Preț: 100.35 lei -

Preț: 108.09 lei

Preț: 108.09 lei -

Preț: 115.42 lei

Preț: 115.42 lei -

Preț: 106.04 lei

Preț: 106.04 lei -

Preț: 91.77 lei

Preț: 91.77 lei -

Preț: 90.64 lei

Preț: 90.64 lei -

Preț: 81.66 lei

Preț: 81.66 lei -

Preț: 99.60 lei

Preț: 99.60 lei -

Preț: 96.93 lei

Preț: 96.93 lei -

Preț: 99.30 lei

Preț: 99.30 lei -

Preț: 120.26 lei

Preț: 120.26 lei -

Preț: 103.74 lei

Preț: 103.74 lei -

Preț: 100.98 lei

Preț: 100.98 lei -

Preț: 100.76 lei

Preț: 100.76 lei -

Preț: 89.09 lei

Preț: 89.09 lei -

Preț: 115.94 lei

Preț: 115.94 lei -

Preț: 101.24 lei

Preț: 101.24 lei -

Preț: 125.13 lei

Preț: 125.13 lei -

Preț: 89.50 lei

Preț: 89.50 lei -

Preț: 101.88 lei

Preț: 101.88 lei -

Preț: 139.63 lei

Preț: 139.63 lei -

Preț: 93.85 lei

Preț: 93.85 lei -

Preț: 106.45 lei

Preț: 106.45 lei -

Preț: 89.91 lei

Preț: 89.91 lei -

Preț: 107.92 lei

Preț: 107.92 lei -

Preț: 77.02 lei

Preț: 77.02 lei -

Preț: 111.76 lei

Preț: 111.76 lei -

Preț: 132.88 lei

Preț: 132.88 lei -

Preț: 112.11 lei

Preț: 112.11 lei -

Preț: 83.94 lei

Preț: 83.94 lei -

Preț: 88.62 lei

Preț: 88.62 lei -

Preț: 105.41 lei

Preț: 105.41 lei -

Preț: 87.84 lei

Preț: 87.84 lei -

Preț: 97.34 lei

Preț: 97.34 lei -

Preț: 129.78 lei

Preț: 129.78 lei -

Preț: 100.57 lei

Preț: 100.57 lei

Preț: 90.72 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 136

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.36€ • 18.85$ • 14.58£

17.36€ • 18.85$ • 14.58£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400030620

ISBN-10: 1400030625

Pagini: 306

Dimensiuni: 140 x 203 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Vintage Publishing

Seria Vintage Contemporaries

ISBN-10: 1400030625

Pagini: 306

Dimensiuni: 140 x 203 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Vintage Publishing

Seria Vintage Contemporaries

Notă biografică

Steve Yarbrough’s honors include the Mississippi Authors Award, the California Book Award, and a third from the Mississippi Institute of Arts and Letters. The author of two previous novels and three collections of stories, he is a native of the Delta town of Indianola and now lives in Fresno, California.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

ONE

The rolling store was one of two old school buses his uncle Alvin had bought after they were deemed unsafe to haul children. The one Dan drove in the summer of 1943 had a couple holes in the floorboard. Half the time the starter wouldn't work, and then he'd have to put the transmission in neutral, get out and turn the hand crank. The rear wheels, which had been pulled off a cotton trailer, were bigger than the ones in front, so the bus always looked like it was headed downhill.

His uncle had outfitted each bus with display cases, candy counters, a soft-drink box and a Deepfreeze. Dan and the other driver, L.C., sold farmers and hoe hands everything from chocolate bars and Nehi sodas to coal-oil lamps and radios. Gas rationing had made the routes more successful than they otherwise might have been, since a lot of folks couldn't get into town very often.

Alvin never had any trouble getting gas, because he never had any trouble getting sugar, something the bootleggers couldn't do without. He traded them hundred-pound sacks of it for cases of bootleg whiskey, which in turn he passed on to the members of the local rationing board. "Seem like making tough decisions gives a fellow a case of cotton mouth," Dan had heard him say. "That's the thirstiest bunch of doctors and lawyers and bankers I ever saw."

His uncle had a special knack for handling people, which usually involved satisfying their appetites. You could tell a lot about a man, he always said, by watching what he put in his mouth.

Dan drove into the lot behind Alvin's country store and parked next to the other bus. L.C. finished first every day. His route was shorter, his bus drove a little better and he generally ignored the thirty-five-mile-an-hour speed limit.

Dan had asked him once if he didn't feel bad about breaking the law when everybody else was trying to conserve gas for the troops, and L.C. had wrinkled his nose, as he was apt to whenever something amused him. "Let me ask you, Dan," he said. "Do your uncle feel bad about breaking the law?"

"He don't break it. He just bends it a little."

L.C. laughed. "For him, it bends. But for a nigger, it just too stiff. We working with a lot less flexibility than y'all are."

L.C. said y'all a lot, and we, constantly calling attention to the differences between them. He also liked to employ a phrase he'd heard last Easter, when his momma made him go to church: parallel universes. "That's what the preacher say we living in, Dan. You got your universe, I got mine. I see you spinning by, you see me, time to time we both wave, say hey. But never the twain shall meet--and that last part come straight from the Bible." When Dan protested that he couldn't see what the parallel-universe theory had to do with Easter, L.C. said, "Course not. Over there in y'all's universe, Easter mean colored eggs. But we ain't got no eggs to color. Sure enough interested in that rising part, though."

Today, as always, L.C. was waiting for him, sitting atop the propane tank, his dusty work shoes lying on the ground and his big toe protruding from a hole in one sock. "How much you sold, Dan?"

"Took in close to thirty dollars."

L.C. whistled. "That's the profitable route. I had me that route, I'd be tempted to steal your old uncle blind."

"You could steal from him anyway, if you got a mind to."

"Naw. I take from him, he might take from me."

"What could he take? You ain't got nothing anyway, far as I can tell."

"Got myself. He could take and give it to the army."

"Army don't want it. They got all the bus drivers they need. Army wants fighting men."

"Army'll make the niggers fight, before it's all said and done. You know old Jeff Davis wanted the same thing in the Civil War, make the niggers march with Robert Lee?"

"Who told you that?"

L.C. looked at him. "Just imagine my granddaddy covering your granddaddy's ass while he go crawling out the bushes toward them Yankees."

"You ain't got a granddaddy."

"Everybody got a granddaddy," L.C. said. You could almost see the curtain falling over his face. Sooner or later, the banter always turned serious, and Dan could never quite figure out when it was going to happen in time to shut his mouth.

L.C. jumped down, all business now, and slipped on his shoes. Together, they carried the small Deepfreezes off the buses and balanced them, one at a time, on a handcart, then rolled them over to the tractor shed that served as his uncle's warehouse and plugged them in. Next day they'd restock them with ice-cream sandwiches, fruit Popsicles, pig tails and neck bones.

After they washed up at the sink, L.C. said he was going home, and he set off down the road. Dan walked around to the front of the store and saw his father's old pickup parked near the porch. He opened the screen door and stepped inside.

The place smelled of molasses, salt meat, leather and patent medicine. Horse collars, trace chains and hame straps hung on the walls, and the shelves were filled with canned goods and hardware. Toward the rear, stacked almost to the ceiling, were several hundred cases of sanitary napkins--all the sanitary napkins, his uncle said, in the Delta. He'd concocted some deal with a distributor over in Greenville that allowed him, at least briefly, to corner the market, and women had been streaming into the store for days, coming in groups of four and five from as far away as Clarksdale and Yazoo City, buying in bulk.

The store was empty except for L.C.'s momma, Rosetta, who sat behind the cash register, fanning herself with a copy of Negro Digest. "Where L.C. go off to?" she asked.

"Went on home."

"Now that ain't nothing but a bald-face lie." Her eyes followed a fly that buzzed back and forth above the till. "Question is, L.C. lie to you or get you to lie to me?"

Dan walked over to the counter, lifted the top off a big jar and grabbed a handful of oatmeal cookies. "I don't believe L.C. lies to me," he said.

"Course he do. And lying within limits is all right."

"That ain't what it says in the Bible."

"Colored folks' Bible or white folks'?"

"I thought we was all using the same one."

The fly made the mistake of lighting on the counter. Rosetta reached over with her magazine and swatted it. "Y'all's Bible may be the same book," she said, flicking the body off the cover, "but the words got a whole different meaning."

"You saying it's all right for L.C. to lie to white folks but not colored?"

"There's niggers I've knowed forty years and ain't yet spoke a word of truth to. I'm saying it's not all right to lie to his momma."

"Our Bible don't make them kinds of distinctions," Dan said. "I reckon the Lord was scared we'd get confused." Stuffing a cookie into his mouth, he walked over to the back of the store and opened the door to his uncle's office.

His mother was sitting on the edge of his desk, her long, smooth legs hanging off the far side, and his uncle was in the coaster chair. It looked like maybe they'd been disagreeing about something, because his mother's face was flushed. She had the milky white complexion that often accompanies red hair, and if she got agitated, you could always tell.

His uncle, though, seemed perfectly calm, maybe even a little amused. His hands were locked behind his head, and he'd rocked back in the coaster chair and crossed his legs. One end of his mustache was arched just a little, like he was doing his best not to grin. "How'd it go today, partner?" he said.

"Not too bad. I'm starting to have a problem with that Deepfreeze, though."

"What kind of problem?"

"Had to throw out a few Popsicles and some of the ice cream--the stuff thawed out and started running. That freezer may have a bad seal on it."

"Naw, there ain't nothing wrong with that freezer. It's just too damn hot. Thermometer on the wall outside hit a hundred by three o'clock." Alvin's eyes had that little gleam that appeared whenever he'd figured out a way to get something for nothing. "Tell you what you do, Daniel. You know the old gin up there at Fairway Crossroads?"

"The one that went out of business?"

"Yep. You probably get to Fairway along about eating time. Well, I happen to know the power's still on at the gin. So tomorrow, carry you an extension cord and pull up there to the loading dock. The outlet's right there beside the door to the press room. Plug that Deepfreeze in and set back and eat you a good long lunch, and when you're through, that freezer'll be nice and cold again."

His mother looked over at him. "You may have to run me up to Memphis the beginning of next week, Dan. I was trying to get your uncle to do it, but he claims he doesn't have time."

"No," Alvin said, "I didn't say I don't have time. I said I may not have time. I said just wait a little while and we'll see."

"I don't know that I can wait. That ad in the Commercial said they'd be getting the fabric on Monday. It'll go in no time." She got down off the desk and picked up her purse. "I guess pretty soon, the direction things are headed, we'll all be naked."

The springs in Alvin's chair squeaked as he rocked forward and stood up. Taking his cup, giving it a quick sniff, he walked over to the metal urn, drew himself some coffee and took a long swallow. "I seriously doubt," he said, "that anybody's going naked."

TWO

Behind the wheel, his mother posed a threat to herself as well as everybody else, so he drove home. When they pulled into the yard, he cut the motor, and for a minute or two they just sat there. More often than not, neither one of them wanted to go inside the house, preferring instead to postpone walking through the door into all that silence.

He thought of that instant as one of confrontation and imagined she did, too, though what she confronted, he suspected, was a lot different from what he had to face. He believed, too, that she could name her problem and could've recited in her mind a whole set of specific actions or nonactions that had brought it to pass. Whereas his problems were vague, ill-defined. He didn't like where he was, and he didn't like what he'd most likely become if he managed to survive the war that was waiting for him a few months down the road. But he didn't know where else, or what else, he'd rather be. His imagination, he guessed, was a lot like an acre of buckshot. Nothing much grew there.

He opened his door and got out, as did his mother. Brushing a loose strand from her eyes, she looked at him across the hood of the truck. "I thawed out a couple pork chops," she said. "How does that sound?"

"All right."

"Just all right?"

"It sounds good," he said.

"Good," she said. "I'm glad you think so."

Inside, she stepped quickly into the kitchen. He kicked off his shoes and set them on a few sheets of old newspaper in the corner of the living room. His father had always done that when he came in from the field, and Dan wanted everything left just the way it had been when his father was alive.

The one time he and his mother had fought was the day he saw her boxing up a bunch of his father's pants and shirts, getting ready to carry them to the church for the clothing drive. He'd pulled the box from her hands, dumped the clothes on the bed, thrown the box on the floor and stomped it flat. She slapped his face that day, then burst into tears and locked herself in the bathroom. She didn't come out for hours, no matter how hard he begged. When she finally did emerge, her eyes were dry and her voice steady. "Okay, have it your way," she said. "But if you mean to be treated like the man of the house, you need to go ahead and be one."

She'd opened a bottle of his uncle's whiskey, and Dan had sat beside her on the couch, sipping at his drink while she poured herself one after another. He'd drunk beer a couple times but had never tasted whiskey and didn't know how it burned in your nose; his mother laughed every time he took a swallow.

She told a lot of stories that night about folks he'd never heard of, people she'd known growing up down in Jackson or met at dances she'd been to. Some colored musicians from New Orleans, she said, used to come through once a year, and she and a few of her friends would slip off to a roadhouse just outside Raymond and watch them play instruments she'd never seen before. One of them had some kind of long silver pipe that made the eeriest sounds you'd ever heard; he'd get down on his knees while he played, blowing sound right into the floor.

She talked until she began to slur her words, then yawned and tried to stand. After helping her to bed, he walked out back and made himself throw up, just to get the taste out of his mouth.

Tonight they ate without saying much, and while he was clearing the dishes, she went into the living room and stuck a Roy Acuff record on the phonograph. "Come on in here," she called. "Let's listen to some music."

He figured she'd have the whiskey out again, and he was right. A bottle and a pair of glasses stood on the coffee table, next to the illustrated Bible that had belonged to his grandmother. He walked over, picked the bottle up and set it on an end table.

She watched him the whole time. "Jesus turned the water into wine," she said.

"He didn't turn it into moonshine."

"This is not moonshine." She examined the label on the bottle. "This is bonded whiskey, a hundred and one proof, made legally in Claremont, Kentucky."

"Maybe it's legal to make it there, but it ain't to drink it here."

She poured some into one of the glasses. "Well, then go ahead and turn me in." She lifted the glass and took a swallow, then coughed and held a hand to her mouth, her eyes watering.

From the Hardcover edition.

The rolling store was one of two old school buses his uncle Alvin had bought after they were deemed unsafe to haul children. The one Dan drove in the summer of 1943 had a couple holes in the floorboard. Half the time the starter wouldn't work, and then he'd have to put the transmission in neutral, get out and turn the hand crank. The rear wheels, which had been pulled off a cotton trailer, were bigger than the ones in front, so the bus always looked like it was headed downhill.

His uncle had outfitted each bus with display cases, candy counters, a soft-drink box and a Deepfreeze. Dan and the other driver, L.C., sold farmers and hoe hands everything from chocolate bars and Nehi sodas to coal-oil lamps and radios. Gas rationing had made the routes more successful than they otherwise might have been, since a lot of folks couldn't get into town very often.

Alvin never had any trouble getting gas, because he never had any trouble getting sugar, something the bootleggers couldn't do without. He traded them hundred-pound sacks of it for cases of bootleg whiskey, which in turn he passed on to the members of the local rationing board. "Seem like making tough decisions gives a fellow a case of cotton mouth," Dan had heard him say. "That's the thirstiest bunch of doctors and lawyers and bankers I ever saw."

His uncle had a special knack for handling people, which usually involved satisfying their appetites. You could tell a lot about a man, he always said, by watching what he put in his mouth.

Dan drove into the lot behind Alvin's country store and parked next to the other bus. L.C. finished first every day. His route was shorter, his bus drove a little better and he generally ignored the thirty-five-mile-an-hour speed limit.

Dan had asked him once if he didn't feel bad about breaking the law when everybody else was trying to conserve gas for the troops, and L.C. had wrinkled his nose, as he was apt to whenever something amused him. "Let me ask you, Dan," he said. "Do your uncle feel bad about breaking the law?"

"He don't break it. He just bends it a little."

L.C. laughed. "For him, it bends. But for a nigger, it just too stiff. We working with a lot less flexibility than y'all are."

L.C. said y'all a lot, and we, constantly calling attention to the differences between them. He also liked to employ a phrase he'd heard last Easter, when his momma made him go to church: parallel universes. "That's what the preacher say we living in, Dan. You got your universe, I got mine. I see you spinning by, you see me, time to time we both wave, say hey. But never the twain shall meet--and that last part come straight from the Bible." When Dan protested that he couldn't see what the parallel-universe theory had to do with Easter, L.C. said, "Course not. Over there in y'all's universe, Easter mean colored eggs. But we ain't got no eggs to color. Sure enough interested in that rising part, though."

Today, as always, L.C. was waiting for him, sitting atop the propane tank, his dusty work shoes lying on the ground and his big toe protruding from a hole in one sock. "How much you sold, Dan?"

"Took in close to thirty dollars."

L.C. whistled. "That's the profitable route. I had me that route, I'd be tempted to steal your old uncle blind."

"You could steal from him anyway, if you got a mind to."

"Naw. I take from him, he might take from me."

"What could he take? You ain't got nothing anyway, far as I can tell."

"Got myself. He could take and give it to the army."

"Army don't want it. They got all the bus drivers they need. Army wants fighting men."

"Army'll make the niggers fight, before it's all said and done. You know old Jeff Davis wanted the same thing in the Civil War, make the niggers march with Robert Lee?"

"Who told you that?"

L.C. looked at him. "Just imagine my granddaddy covering your granddaddy's ass while he go crawling out the bushes toward them Yankees."

"You ain't got a granddaddy."

"Everybody got a granddaddy," L.C. said. You could almost see the curtain falling over his face. Sooner or later, the banter always turned serious, and Dan could never quite figure out when it was going to happen in time to shut his mouth.

L.C. jumped down, all business now, and slipped on his shoes. Together, they carried the small Deepfreezes off the buses and balanced them, one at a time, on a handcart, then rolled them over to the tractor shed that served as his uncle's warehouse and plugged them in. Next day they'd restock them with ice-cream sandwiches, fruit Popsicles, pig tails and neck bones.

After they washed up at the sink, L.C. said he was going home, and he set off down the road. Dan walked around to the front of the store and saw his father's old pickup parked near the porch. He opened the screen door and stepped inside.

The place smelled of molasses, salt meat, leather and patent medicine. Horse collars, trace chains and hame straps hung on the walls, and the shelves were filled with canned goods and hardware. Toward the rear, stacked almost to the ceiling, were several hundred cases of sanitary napkins--all the sanitary napkins, his uncle said, in the Delta. He'd concocted some deal with a distributor over in Greenville that allowed him, at least briefly, to corner the market, and women had been streaming into the store for days, coming in groups of four and five from as far away as Clarksdale and Yazoo City, buying in bulk.

The store was empty except for L.C.'s momma, Rosetta, who sat behind the cash register, fanning herself with a copy of Negro Digest. "Where L.C. go off to?" she asked.

"Went on home."

"Now that ain't nothing but a bald-face lie." Her eyes followed a fly that buzzed back and forth above the till. "Question is, L.C. lie to you or get you to lie to me?"

Dan walked over to the counter, lifted the top off a big jar and grabbed a handful of oatmeal cookies. "I don't believe L.C. lies to me," he said.

"Course he do. And lying within limits is all right."

"That ain't what it says in the Bible."

"Colored folks' Bible or white folks'?"

"I thought we was all using the same one."

The fly made the mistake of lighting on the counter. Rosetta reached over with her magazine and swatted it. "Y'all's Bible may be the same book," she said, flicking the body off the cover, "but the words got a whole different meaning."

"You saying it's all right for L.C. to lie to white folks but not colored?"

"There's niggers I've knowed forty years and ain't yet spoke a word of truth to. I'm saying it's not all right to lie to his momma."

"Our Bible don't make them kinds of distinctions," Dan said. "I reckon the Lord was scared we'd get confused." Stuffing a cookie into his mouth, he walked over to the back of the store and opened the door to his uncle's office.

His mother was sitting on the edge of his desk, her long, smooth legs hanging off the far side, and his uncle was in the coaster chair. It looked like maybe they'd been disagreeing about something, because his mother's face was flushed. She had the milky white complexion that often accompanies red hair, and if she got agitated, you could always tell.

His uncle, though, seemed perfectly calm, maybe even a little amused. His hands were locked behind his head, and he'd rocked back in the coaster chair and crossed his legs. One end of his mustache was arched just a little, like he was doing his best not to grin. "How'd it go today, partner?" he said.

"Not too bad. I'm starting to have a problem with that Deepfreeze, though."

"What kind of problem?"

"Had to throw out a few Popsicles and some of the ice cream--the stuff thawed out and started running. That freezer may have a bad seal on it."

"Naw, there ain't nothing wrong with that freezer. It's just too damn hot. Thermometer on the wall outside hit a hundred by three o'clock." Alvin's eyes had that little gleam that appeared whenever he'd figured out a way to get something for nothing. "Tell you what you do, Daniel. You know the old gin up there at Fairway Crossroads?"

"The one that went out of business?"

"Yep. You probably get to Fairway along about eating time. Well, I happen to know the power's still on at the gin. So tomorrow, carry you an extension cord and pull up there to the loading dock. The outlet's right there beside the door to the press room. Plug that Deepfreeze in and set back and eat you a good long lunch, and when you're through, that freezer'll be nice and cold again."

His mother looked over at him. "You may have to run me up to Memphis the beginning of next week, Dan. I was trying to get your uncle to do it, but he claims he doesn't have time."

"No," Alvin said, "I didn't say I don't have time. I said I may not have time. I said just wait a little while and we'll see."

"I don't know that I can wait. That ad in the Commercial said they'd be getting the fabric on Monday. It'll go in no time." She got down off the desk and picked up her purse. "I guess pretty soon, the direction things are headed, we'll all be naked."

The springs in Alvin's chair squeaked as he rocked forward and stood up. Taking his cup, giving it a quick sniff, he walked over to the metal urn, drew himself some coffee and took a long swallow. "I seriously doubt," he said, "that anybody's going naked."

TWO

Behind the wheel, his mother posed a threat to herself as well as everybody else, so he drove home. When they pulled into the yard, he cut the motor, and for a minute or two they just sat there. More often than not, neither one of them wanted to go inside the house, preferring instead to postpone walking through the door into all that silence.

He thought of that instant as one of confrontation and imagined she did, too, though what she confronted, he suspected, was a lot different from what he had to face. He believed, too, that she could name her problem and could've recited in her mind a whole set of specific actions or nonactions that had brought it to pass. Whereas his problems were vague, ill-defined. He didn't like where he was, and he didn't like what he'd most likely become if he managed to survive the war that was waiting for him a few months down the road. But he didn't know where else, or what else, he'd rather be. His imagination, he guessed, was a lot like an acre of buckshot. Nothing much grew there.

He opened his door and got out, as did his mother. Brushing a loose strand from her eyes, she looked at him across the hood of the truck. "I thawed out a couple pork chops," she said. "How does that sound?"

"All right."

"Just all right?"

"It sounds good," he said.

"Good," she said. "I'm glad you think so."

Inside, she stepped quickly into the kitchen. He kicked off his shoes and set them on a few sheets of old newspaper in the corner of the living room. His father had always done that when he came in from the field, and Dan wanted everything left just the way it had been when his father was alive.

The one time he and his mother had fought was the day he saw her boxing up a bunch of his father's pants and shirts, getting ready to carry them to the church for the clothing drive. He'd pulled the box from her hands, dumped the clothes on the bed, thrown the box on the floor and stomped it flat. She slapped his face that day, then burst into tears and locked herself in the bathroom. She didn't come out for hours, no matter how hard he begged. When she finally did emerge, her eyes were dry and her voice steady. "Okay, have it your way," she said. "But if you mean to be treated like the man of the house, you need to go ahead and be one."

She'd opened a bottle of his uncle's whiskey, and Dan had sat beside her on the couch, sipping at his drink while she poured herself one after another. He'd drunk beer a couple times but had never tasted whiskey and didn't know how it burned in your nose; his mother laughed every time he took a swallow.

She told a lot of stories that night about folks he'd never heard of, people she'd known growing up down in Jackson or met at dances she'd been to. Some colored musicians from New Orleans, she said, used to come through once a year, and she and a few of her friends would slip off to a roadhouse just outside Raymond and watch them play instruments she'd never seen before. One of them had some kind of long silver pipe that made the eeriest sounds you'd ever heard; he'd get down on his knees while he played, blowing sound right into the floor.

She talked until she began to slur her words, then yawned and tried to stand. After helping her to bed, he walked out back and made himself throw up, just to get the taste out of his mouth.

Tonight they ate without saying much, and while he was clearing the dishes, she went into the living room and stuck a Roy Acuff record on the phonograph. "Come on in here," she called. "Let's listen to some music."

He figured she'd have the whiskey out again, and he was right. A bottle and a pair of glasses stood on the coffee table, next to the illustrated Bible that had belonged to his grandmother. He walked over, picked the bottle up and set it on an end table.

She watched him the whole time. "Jesus turned the water into wine," she said.

"He didn't turn it into moonshine."

"This is not moonshine." She examined the label on the bottle. "This is bonded whiskey, a hundred and one proof, made legally in Claremont, Kentucky."

"Maybe it's legal to make it there, but it ain't to drink it here."

She poured some into one of the glasses. "Well, then go ahead and turn me in." She lifted the glass and took a swallow, then coughed and held a hand to her mouth, her eyes watering.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

"The highest kind of art, full of subtlety and sensitivity.” –Dallas Morning News

"Yarbrough writes with quiet compassion . . . [about] what it means to be American, and all the unexpected–and often unwarranted–sacrifices that identity might comprise." –The New York Times Book Review

“In this powerful, understated novel, [Yarbrough] finds a way to describe how fleeting moments between people slowly accrue and gather the heaviness of fate.” –The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

“Vivid and dramatic. . . . Prisoners of War is smart and entertaining.” –San Francisco Chronicle

“Yarbrough has created a timely war novel that is refreshingly unpredictable yet as comfortable as an old boot.” –The Oregonian

"Yarbrough writes with quiet compassion . . . [about] what it means to be American, and all the unexpected–and often unwarranted–sacrifices that identity might comprise." –The New York Times Book Review

“In this powerful, understated novel, [Yarbrough] finds a way to describe how fleeting moments between people slowly accrue and gather the heaviness of fate.” –The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

“Vivid and dramatic. . . . Prisoners of War is smart and entertaining.” –San Francisco Chronicle

“Yarbrough has created a timely war novel that is refreshingly unpredictable yet as comfortable as an old boot.” –The Oregonian

Premii

- PEN/Faulkner Award Nominee, 2005