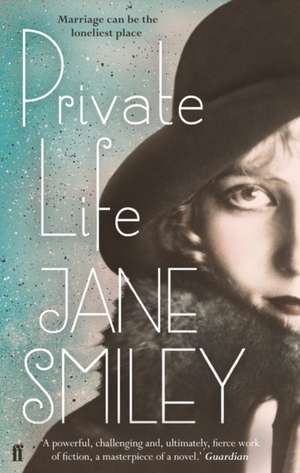

Private Life

Autor Jane Smileyen Limba Engleză Paperback – 2 mar 2011

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 71.53 lei 3-5 săpt. | +16.06 lei 4-10 zile |

| FABER & FABER – 2 mar 2011 | 71.53 lei 3-5 săpt. | +16.06 lei 4-10 zile |

| Anchor Books – 31 mai 2011 | 135.89 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 71.53 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 107

Preț estimativ în valută:

13.69€ • 14.24$ • 11.30£

13.69€ • 14.24$ • 11.30£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 24 martie-07 aprilie

Livrare express 07-13 martie pentru 26.05 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780571258758

ISBN-10: 0571258751

Pagini: 496

Dimensiuni: 128 x 198 x 34 mm

Greutate: 0.39 kg

Ediția:Main

Editura: FABER & FABER

ISBN-10: 0571258751

Pagini: 496

Dimensiuni: 128 x 198 x 34 mm

Greutate: 0.39 kg

Ediția:Main

Editura: FABER & FABER

Recenzii

"Masterly. . . .[A] precise, compelling depiction of a singular woman." -"The New Yorker" "Extraordinarily powerful. . . .It's not often that a work as exceptional as this comes along in contemporary American letters." -"Washington Post" "Smiley's best novel yet. . . . [A] heartbreaking, bitter, and gorgeous story." -"The Atlantic Monthly" "Remarkable. . . . With its quietly accruing power, "[Private Life" is] the kind of book that puts the lie to those who claim that great novelists produce their best work early and spend the rest of their lives gilding the lily." --"Chicago Tribune"" ""Has a Jamesian twist of the unforeseen, but it's achieved with a sureness of hand that's all [Smiley's] own." --"The New York Times Book Review"" ""Smiley's eye is keen, and the book's historical pageant is often mesmerizing and often elegantly composed. . . . A quiet tragedy." --"The Seattle Times"" """Private Life," perhaps Jane Smiley's best novel sin

Notă biografică

JANE SMILEY is the author of numerous novels, including A Thousand Acres, which was awarded the Pulitzer Prize, and most recently, Golden Age, the concluding volume of The Last Hundred Years trilogy. She is also the author of five works of nonfiction and a series of books for young adults. A member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, she has also received the PEN Center USA Lifetime Achievement Award for Literature. She lives in Northern California.

Extras

PART ONE

1883

For a while, they lived in town. She had a particular and vivid memory of that time: she was running, as it seemed she always did, back and forth from one end of town to the other. She was fast and gloried in it. She wasn’t racing against anyone or getting into trouble, she was just running and looking at things. She ran fast enough so that she could feel her heavy blond hair stream out behind her, subside across her back, stream out again. She passed one house after another.

At the far end of town, there was a pleasant large house where some ladies lived, though they never talked to her, nor she to them. She remembered how, one day, she came to a halt in front of this house and one of the ladies, a tall beauty, was standing on the porch, dressed in an elegant white embroidered gown with a snowy eyelet skirt. Margaret stared at her, and the lady smiled. Margaret thought that she had never seen anything as beautiful as that dress in her life, which at the time seemed rather long. When the lady wafted back into the house, Margaret turned and pelted home, where she found her mother in the back parlor, sewing. As soon as Margaret entered the room, out of breath, she saw that her mother was sewing a copy of the dress she had seen on the beautiful lady. She exclaimed, “I saw that dress! I saw that dress today!” Then she went up and touched the eyelet. Her mother, Lavinia, didn’t reprimand her, but finished the seam she was sewing, and broke the thread between her teeth. Then she said, “Perhaps you did. But don’t tell your father.” It was years before Margaret realized that the pleasant house at the far end of town was a brothel, and that, from time to time, her mother sewed dresses for the ladies to make a little extra money. In Margaret’s mind, these dresses were always white. When she was older, though, and recalled this, Lavinia said that it hadn’t happened, it couldn’t have happened; Margaret must have read it in a book.

What had happened, what Margaret should have remembered, was that her brother Lawrence, who would have been thirteen then, had left the house with her one day and taken her to a public hanging. No one had stopped him, because Lavinia was giving birth—to Elizabeth—and her father, famous all over town as Dr. Mayfield (Margaret thought of him as “Dr. Mayfield,” too, he was that imposing), was attending the birth. Lily, the housekeeper, was occupied with Beatrice, who was two. It was said that Lawrence and Margaret left the house and were gone for hours before anyone noticed. But no one suspected that Lawrence, a studious boy, would have taken her to the hanging. Ben, yes—Ben was rowdy and adventuresome, though two years younger than Lawrence. The whole episode was a family legend, and part of the legend was that Margaret didn’t remember a thing about it. “Margaret looks on the bright side,” said Lavinia. “As well she should.” From time to time, though, Margaret had a ghostly recollection of this bit or that bit—of her hand reaching up into Lawrence’s hand, or of him handing her a bit of a crab apple, or of her bonnet hanging over her eyes so that she couldn’t see anything except her feet. He might have sat her on his shoulders—he sometimes did that when she was very young. Nevertheless, it was a fugitive memory, however dramatic.

But Margaret remembered other things that she would have preferred to forget. She remembered that when Ben was thirteen he went with some cronies down to the railyards. They found a blasting cap, which one of the fellows attached to the end of a short length of iron rod that they had also found. Employing this rod, they rubbed the blasting cap against some brickwork to see what might happen. When it exploded, the rod flew out of the boy’s hand and entered Ben’s skull above the ear. He was killed instantly. None of the other boys was hurt, and they carried the body home as best they could. Dr. Mayfield met them at the door, and this was the first news they had of the death of Ben.

That winter, Lawrence contracted measles, which led to an inflammation of the brain. The source of the original infection was what Lavinia had always feared, a child who was brought to see Dr. Mayfield. Elizabeth, Beatrice, and Margaret succumbed as well. But they were fairly young, and Lawrence was almost sixteen at the time. They lived and he did not.

And then, one evening about six months after the death of Lawrence, for reasons of his own that Lavinia later said had to do with melancholic propensities, Dr. Mayfield retrieved Ben’s rifle from the storeroom behind the kitchen and shot himself in his office. Lavinia found him—she had thought he was still out with a patient, but, upon awakening very late, she heard the horse whinny out in the stable. She went to Dr. Mayfield’s office to investigate and discovered the corpse. Margaret remembered that night—the sounds of running feet and doors slamming, the whinny of a horse, and a shout either half rousing her or weaving into her slumber. What she remembered most clearly was that when she and her sisters got up in the morning, there was once again a large closed coffin in the parlor. Their father was gone, and Lavinia, who had been sickly from so many pregnancies and so much grief, was a different person, one the girls had never known before. She was entirely dressed, her bed was made, and from that day forward, she never complained again of the headache or anything else. Margaret was eight; Beatrice had just turned six; Elizabeth was not quite three. On the day after the funeral, which Margaret also remembered, Lavinia moved the girls to her father’s farm—it was the practical thing to do, and Lavinia said that they were lucky to be able to do so. She told Margaret, because she was the oldest, that death was the most essential part of life, and that they must make the best of it. Margaret always remembered that.

Gentry Farm, not far from Darlington, down toward the Missouri River, was famous in the neighborhood, a beautiful expanse of fertile prairie that John Gentry and his own father had broken in 1828. Before the War Between the States, Lavinia’s father and grandfather owned seventy-two slaves, quite a few more than was usual in Missouri—they raised hemp, tobacco, corn, and hogs. When Lavinia was twelve, John Gentry gave his oath to support the Union, unlike several of his neighbors. Two of his cousins went off to join the Confederacy. After the war, John Gentry’s loyalties were questioned all around, and so he married his daughters to suitors of unimpeachable Union sympathies. Martha married a man from Iowa who fought with the Fourth Iowa Infantry; Harriet married an Irishman from Chicago; Louisa married one of those radical Germans from the Osage River Valley, who, though her grandfather never liked him, was a rich man and an accomplished farmer. And after the war, John Gentry managed to hold off the bushwhacking Rebel sympathizers by being well armed at all times and a notoriously excellent shot. They did burn down his corncrib once, and steal two of his horses. He knew them, of course. Boone County, Callaway County, and Cole County were wild patchworks of Union and Rebel sympathizers, and though blood didn’t run as high there as it did out to the west, your neighbor could always tip his hat to you during the day and come to hang you that same night. John Gentry said that you would think that Lincoln, a man who knew both Illinois and Kentucky, would have given going to war lengthier consideration than he did, but those folks from Massachusetts and New York, who didn’t have a thing to lose, got his ear, and that was that for a place like Missouri, which remained a stew of differing loyalties and long-standing resentments for many years.

Lavinia never expressed opinions about the war—for her, the three girls were occupation enough. She was frank—their assets were few—and as they grew into young ladies, her principal task was to cultivate them. John Gentry had a piano, and so Beatrice was put to learning how to play it. Lavinia had a sewing machine, and so Elizabeth was put to learning how to use it. Dr. Mayfield had left quite a few books, and so Margaret, never adept with her hands, was put to reading them. Quite often, she would read while Beatrice practiced her fingerings and Elizabeth and her mother sewed. Margaret liked to read Dickens best—The Old Curiosity Shop was a great favorite, and A Tale of Two Cities. Her grandfather, sitting in the circle smoking his pipe, enjoyed Martin Chuzzlewit for Dickens’s faithful portayal of the sad life of those folks who lived over by Cairo, Illinois, a spot on the map as different from the Kingdom of Callaway County, Missouri, as white was from black. She also read Ragged Dick and Marie Bertrand, which were, of course, by her mother’s favorite author, Mr. Alger. They were most excited to receive a copy of Mr. Alger’s Bob Burton, or, The Young Ranchman of the Missouri, as a gift from Aunt Louisa, but though they did read it, John Gentry was dismayed to discover that the Missouri River in question was in Iowa, and was not their Missouri, the real Missouri, which was in the state of Missouri and, he always told everyone, the true main branch of the Mississippi, and therefore the longest river in the entire world. Another book that came to mean a good deal to Margaret was Two Years Before the Mast, by Mr. Dana. She read it to her sisters twice, all the while making bright pictures in her own mind of the wild and inaccessible coast of California. These pictures subsequently turned out to be entirely wrong.

Alice, her grandfather’s cook, taught them how to make biscuits, coffee, doughnuts, flapjacks, and piecrust. Of farmwork, the girls did little, but they did pick apples, pears, plums, and peaches from her grandfather’s trees, and blackberries and raspberries and gooseberries from his bushes. They were taught to make jams and cordials, and to think of Missouri as an earthly paradise.

Lavinia got pattern books and designed their dresses so as to minimize their disadvantages of appearance: With her blue eyes and fair hair, Margaret wore only shades of blue. Elizabeth, who was not fair, was allowed blue and green. Beatrice, dark like their father, wore deep reds, sometimes pink, and occasionally a faded and respectable violet. Beatrice grew tall; she had to wear wide sleeves. Elizabeth’s frocks, with their buttons and tucks and insets, always drew the (ever-foreseen male) eye to her slender waist. Margaret’s wrists were a bit thick, according to her mother, so she had to wear gloves into town. The girls trimmed hats. They knitted shawls. They crocheted collars and edgings. They bleached, trimmed, pressed, and set aside in their chests the household linens they would need one day. They embroidered.

For some months when Margaret was sixteen, there was a lengthy discussion of whether they should purchase a loom. Lavinia had heard that there was an enterprising woman in Osage County who made beautiful carpets. Lavinia wondered if this woman might take one of the girls, perhaps Elizabeth, as a student, or even adopt her outright—Lavinia felt that you never knew what an enterprising woman would do, anything was possible. But John Gentry put his foot down, and so the girls learned a humbler craft that winter, braiding rugs from rags. As the rugs grew beneath the fingers of her mother and sisters, Margaret read aloud, as a novelty, a book that had been written by a famous woman from St. Louis named Kate O’Flaherty Chopin. Her grandfather told them how he remembered the very day back in 1855, when Lavinia was still an infant, that the first train belonging to the Pacific Railroad brought down the bridge over the Gasconade River. Many were killed, including Mr. O’Flaherty, Kate Chopin’s father. John Gentry was interested in everything about the railroad, for it had been a great boon to him. Nevertheless, he and Lavinia agreed that the fact that Mrs. Chopin wrote novels for remuneration was an unfortunate outcome of her trials. Beatrice, Elizabeth, and Margaret were encouraged to pity rather than admire her. But books were books—the hoped-for suitors would require an appealing degree of cultivation. Beatrice, with her talents (and good looks), and Elizabeth, with her skills (and her thick mane of chestnut hair), might get as far as Chicago or even New York (in Mr. Alger’s books, the best place to find yourself ending up was New York), but even Margaret could get to St. Louis.

On the farm, talk of St. Louis was constant.

At first, St. Louis came to her as a fall, like a light snow, of names: Chouteau. Vandeventer. Eads. Gratiot. Laclede. St. Charles. Lafayette. Even Grand, which was a boulevard. Shenandoah, Gravois, Soulard. If there was a street name in St. Louis as dull as Oak or Fourth, Margaret never heard it. And every good thing was from there—shoes and boots, silks and nainsooks and Saxony woollens, books, pianos, books of piano music, candy, sugar, chewing tobacco, her mother’s mouton capelet, pearl buttons. There was a vast emporium in St. Louis called Carleton’s which carried goods sent specially from Paris, France, and London, England, and from Japan and China and India (if only tea—Lavinia drank tea). John Gentry seemed to take personal credit for the way St. Louis blossomed just over the eastern horizon of Gentry Farm, and the fact that they could get to St. Louis any day they wanted, on the train from McKittrick, was a source of eternal joy to him (they should have seen the roads, if that was what you wanted to call them, in the Missouri of his youth!). Even so, he went there not more than once in two years.

And then Beatrice was suddenly eighteen years old, a finished product. She could play any number of pieces on the piano, from “Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair” and “Camptown Races” to “Rosalie, the Prairie Flower,” and some more complex pieces without lyrics, such as “Annie and I,” which had three sharps. She could sing if the song in question fell into her range. Her tone was rich and melodious. The time had come to put her on display. A lady Lavinia knew in town had a very nice piano, much nicer than the Gentry piano, which she herself could not play, so, on days when John Gentry had to take a wagon into town anyway for business, he would carry Beatrice along and leave her at Mrs. Larimer’s house on Pennsylvania Street, and Beatrice would play for her. Sometimes, with enough notice, Mrs. Larimer would invite a few friends in to have tea while Beatrice was playing.

The summer Beatrice was eighteen, the cousin of a friend of Mrs. Larimer, a man named Robert Bell, took over the town newspaper. He had money and credentials. What John Gentry knew about Robert Bell, within the first week, was that he was backed by some family capital, he was ambitious, and he had grown up in St. Louis in a big house on Kingshighway, a very wealthy and forward-looking neighborhood.

It was Robert Bell who decreed, young man though he was and new to town, that the Unionists would march at the front of the Fourth of July parade just behind the band; the farm-produce displays, the fire engine, the horse drill, and the mules would march in the middle; and the Rebels (numbering eight by now), dressed in their old Confederate uniforms, would march at the back, behind the Ladies’ Aid Society and the German-American Betterment Society (which dressed in traditional Bavarian costume). He wrote about his plan in the newspaper, alternating discussions of the controversy with news of the war in Cuba, Guam, Puerto Rico, and then the Philippines, until everyone in town had had their say and gotten bored with the War Between the States, especially since the new war seemed to be going so well. According to John Gentry, this strategy of promoting patriotism over infighting was a mark of genius in such a young man, and he went by the office of the newspaper to tell Robert Bell as much. The young man thereupon invited John Gentry and his family to watch the parade from the windows of the newspaper office, which was closed for the afternoon.

To Margaret, Robert Bell was a disappointing sight. He had enormous muttonchop whiskers that only partly disguised his receding chin. His hair was thin and flyaway. His eyes were his best feature, rich blue and much more expressive than his words. He was nicely dressed. But he was considerably shorter than Beatrice—the top of his head came only to the middle of her ear. He made Margaret feel awkward just by standing next to her. He was attentive to them, though. He showed Lavinia to the best chair, which was pulled up right in front of a large open window looking out on Front Street, and then he showed Beatrice to the chair beside that one, and he brought her a cake and a cup of tea. Elizabeth and Margaret he left to fend for themselves, but he had gotten in nice cakes—light, with raspberry filling and marzipan icing, something Margaret had never seen before that day. He also had gotten in enough lemons for real lemonade, which he served with ice. He was comfortable with luxury, just what you would expect in a Bell from St. Louis—Margaret could see this thought passing from Lavinia to her grandfather when they caught each other’s eye and raised an appreciative eyebrow.

1883

For a while, they lived in town. She had a particular and vivid memory of that time: she was running, as it seemed she always did, back and forth from one end of town to the other. She was fast and gloried in it. She wasn’t racing against anyone or getting into trouble, she was just running and looking at things. She ran fast enough so that she could feel her heavy blond hair stream out behind her, subside across her back, stream out again. She passed one house after another.

At the far end of town, there was a pleasant large house where some ladies lived, though they never talked to her, nor she to them. She remembered how, one day, she came to a halt in front of this house and one of the ladies, a tall beauty, was standing on the porch, dressed in an elegant white embroidered gown with a snowy eyelet skirt. Margaret stared at her, and the lady smiled. Margaret thought that she had never seen anything as beautiful as that dress in her life, which at the time seemed rather long. When the lady wafted back into the house, Margaret turned and pelted home, where she found her mother in the back parlor, sewing. As soon as Margaret entered the room, out of breath, she saw that her mother was sewing a copy of the dress she had seen on the beautiful lady. She exclaimed, “I saw that dress! I saw that dress today!” Then she went up and touched the eyelet. Her mother, Lavinia, didn’t reprimand her, but finished the seam she was sewing, and broke the thread between her teeth. Then she said, “Perhaps you did. But don’t tell your father.” It was years before Margaret realized that the pleasant house at the far end of town was a brothel, and that, from time to time, her mother sewed dresses for the ladies to make a little extra money. In Margaret’s mind, these dresses were always white. When she was older, though, and recalled this, Lavinia said that it hadn’t happened, it couldn’t have happened; Margaret must have read it in a book.

What had happened, what Margaret should have remembered, was that her brother Lawrence, who would have been thirteen then, had left the house with her one day and taken her to a public hanging. No one had stopped him, because Lavinia was giving birth—to Elizabeth—and her father, famous all over town as Dr. Mayfield (Margaret thought of him as “Dr. Mayfield,” too, he was that imposing), was attending the birth. Lily, the housekeeper, was occupied with Beatrice, who was two. It was said that Lawrence and Margaret left the house and were gone for hours before anyone noticed. But no one suspected that Lawrence, a studious boy, would have taken her to the hanging. Ben, yes—Ben was rowdy and adventuresome, though two years younger than Lawrence. The whole episode was a family legend, and part of the legend was that Margaret didn’t remember a thing about it. “Margaret looks on the bright side,” said Lavinia. “As well she should.” From time to time, though, Margaret had a ghostly recollection of this bit or that bit—of her hand reaching up into Lawrence’s hand, or of him handing her a bit of a crab apple, or of her bonnet hanging over her eyes so that she couldn’t see anything except her feet. He might have sat her on his shoulders—he sometimes did that when she was very young. Nevertheless, it was a fugitive memory, however dramatic.

But Margaret remembered other things that she would have preferred to forget. She remembered that when Ben was thirteen he went with some cronies down to the railyards. They found a blasting cap, which one of the fellows attached to the end of a short length of iron rod that they had also found. Employing this rod, they rubbed the blasting cap against some brickwork to see what might happen. When it exploded, the rod flew out of the boy’s hand and entered Ben’s skull above the ear. He was killed instantly. None of the other boys was hurt, and they carried the body home as best they could. Dr. Mayfield met them at the door, and this was the first news they had of the death of Ben.

That winter, Lawrence contracted measles, which led to an inflammation of the brain. The source of the original infection was what Lavinia had always feared, a child who was brought to see Dr. Mayfield. Elizabeth, Beatrice, and Margaret succumbed as well. But they were fairly young, and Lawrence was almost sixteen at the time. They lived and he did not.

And then, one evening about six months after the death of Lawrence, for reasons of his own that Lavinia later said had to do with melancholic propensities, Dr. Mayfield retrieved Ben’s rifle from the storeroom behind the kitchen and shot himself in his office. Lavinia found him—she had thought he was still out with a patient, but, upon awakening very late, she heard the horse whinny out in the stable. She went to Dr. Mayfield’s office to investigate and discovered the corpse. Margaret remembered that night—the sounds of running feet and doors slamming, the whinny of a horse, and a shout either half rousing her or weaving into her slumber. What she remembered most clearly was that when she and her sisters got up in the morning, there was once again a large closed coffin in the parlor. Their father was gone, and Lavinia, who had been sickly from so many pregnancies and so much grief, was a different person, one the girls had never known before. She was entirely dressed, her bed was made, and from that day forward, she never complained again of the headache or anything else. Margaret was eight; Beatrice had just turned six; Elizabeth was not quite three. On the day after the funeral, which Margaret also remembered, Lavinia moved the girls to her father’s farm—it was the practical thing to do, and Lavinia said that they were lucky to be able to do so. She told Margaret, because she was the oldest, that death was the most essential part of life, and that they must make the best of it. Margaret always remembered that.

Gentry Farm, not far from Darlington, down toward the Missouri River, was famous in the neighborhood, a beautiful expanse of fertile prairie that John Gentry and his own father had broken in 1828. Before the War Between the States, Lavinia’s father and grandfather owned seventy-two slaves, quite a few more than was usual in Missouri—they raised hemp, tobacco, corn, and hogs. When Lavinia was twelve, John Gentry gave his oath to support the Union, unlike several of his neighbors. Two of his cousins went off to join the Confederacy. After the war, John Gentry’s loyalties were questioned all around, and so he married his daughters to suitors of unimpeachable Union sympathies. Martha married a man from Iowa who fought with the Fourth Iowa Infantry; Harriet married an Irishman from Chicago; Louisa married one of those radical Germans from the Osage River Valley, who, though her grandfather never liked him, was a rich man and an accomplished farmer. And after the war, John Gentry managed to hold off the bushwhacking Rebel sympathizers by being well armed at all times and a notoriously excellent shot. They did burn down his corncrib once, and steal two of his horses. He knew them, of course. Boone County, Callaway County, and Cole County were wild patchworks of Union and Rebel sympathizers, and though blood didn’t run as high there as it did out to the west, your neighbor could always tip his hat to you during the day and come to hang you that same night. John Gentry said that you would think that Lincoln, a man who knew both Illinois and Kentucky, would have given going to war lengthier consideration than he did, but those folks from Massachusetts and New York, who didn’t have a thing to lose, got his ear, and that was that for a place like Missouri, which remained a stew of differing loyalties and long-standing resentments for many years.

Lavinia never expressed opinions about the war—for her, the three girls were occupation enough. She was frank—their assets were few—and as they grew into young ladies, her principal task was to cultivate them. John Gentry had a piano, and so Beatrice was put to learning how to play it. Lavinia had a sewing machine, and so Elizabeth was put to learning how to use it. Dr. Mayfield had left quite a few books, and so Margaret, never adept with her hands, was put to reading them. Quite often, she would read while Beatrice practiced her fingerings and Elizabeth and her mother sewed. Margaret liked to read Dickens best—The Old Curiosity Shop was a great favorite, and A Tale of Two Cities. Her grandfather, sitting in the circle smoking his pipe, enjoyed Martin Chuzzlewit for Dickens’s faithful portayal of the sad life of those folks who lived over by Cairo, Illinois, a spot on the map as different from the Kingdom of Callaway County, Missouri, as white was from black. She also read Ragged Dick and Marie Bertrand, which were, of course, by her mother’s favorite author, Mr. Alger. They were most excited to receive a copy of Mr. Alger’s Bob Burton, or, The Young Ranchman of the Missouri, as a gift from Aunt Louisa, but though they did read it, John Gentry was dismayed to discover that the Missouri River in question was in Iowa, and was not their Missouri, the real Missouri, which was in the state of Missouri and, he always told everyone, the true main branch of the Mississippi, and therefore the longest river in the entire world. Another book that came to mean a good deal to Margaret was Two Years Before the Mast, by Mr. Dana. She read it to her sisters twice, all the while making bright pictures in her own mind of the wild and inaccessible coast of California. These pictures subsequently turned out to be entirely wrong.

Alice, her grandfather’s cook, taught them how to make biscuits, coffee, doughnuts, flapjacks, and piecrust. Of farmwork, the girls did little, but they did pick apples, pears, plums, and peaches from her grandfather’s trees, and blackberries and raspberries and gooseberries from his bushes. They were taught to make jams and cordials, and to think of Missouri as an earthly paradise.

Lavinia got pattern books and designed their dresses so as to minimize their disadvantages of appearance: With her blue eyes and fair hair, Margaret wore only shades of blue. Elizabeth, who was not fair, was allowed blue and green. Beatrice, dark like their father, wore deep reds, sometimes pink, and occasionally a faded and respectable violet. Beatrice grew tall; she had to wear wide sleeves. Elizabeth’s frocks, with their buttons and tucks and insets, always drew the (ever-foreseen male) eye to her slender waist. Margaret’s wrists were a bit thick, according to her mother, so she had to wear gloves into town. The girls trimmed hats. They knitted shawls. They crocheted collars and edgings. They bleached, trimmed, pressed, and set aside in their chests the household linens they would need one day. They embroidered.

For some months when Margaret was sixteen, there was a lengthy discussion of whether they should purchase a loom. Lavinia had heard that there was an enterprising woman in Osage County who made beautiful carpets. Lavinia wondered if this woman might take one of the girls, perhaps Elizabeth, as a student, or even adopt her outright—Lavinia felt that you never knew what an enterprising woman would do, anything was possible. But John Gentry put his foot down, and so the girls learned a humbler craft that winter, braiding rugs from rags. As the rugs grew beneath the fingers of her mother and sisters, Margaret read aloud, as a novelty, a book that had been written by a famous woman from St. Louis named Kate O’Flaherty Chopin. Her grandfather told them how he remembered the very day back in 1855, when Lavinia was still an infant, that the first train belonging to the Pacific Railroad brought down the bridge over the Gasconade River. Many were killed, including Mr. O’Flaherty, Kate Chopin’s father. John Gentry was interested in everything about the railroad, for it had been a great boon to him. Nevertheless, he and Lavinia agreed that the fact that Mrs. Chopin wrote novels for remuneration was an unfortunate outcome of her trials. Beatrice, Elizabeth, and Margaret were encouraged to pity rather than admire her. But books were books—the hoped-for suitors would require an appealing degree of cultivation. Beatrice, with her talents (and good looks), and Elizabeth, with her skills (and her thick mane of chestnut hair), might get as far as Chicago or even New York (in Mr. Alger’s books, the best place to find yourself ending up was New York), but even Margaret could get to St. Louis.

On the farm, talk of St. Louis was constant.

At first, St. Louis came to her as a fall, like a light snow, of names: Chouteau. Vandeventer. Eads. Gratiot. Laclede. St. Charles. Lafayette. Even Grand, which was a boulevard. Shenandoah, Gravois, Soulard. If there was a street name in St. Louis as dull as Oak or Fourth, Margaret never heard it. And every good thing was from there—shoes and boots, silks and nainsooks and Saxony woollens, books, pianos, books of piano music, candy, sugar, chewing tobacco, her mother’s mouton capelet, pearl buttons. There was a vast emporium in St. Louis called Carleton’s which carried goods sent specially from Paris, France, and London, England, and from Japan and China and India (if only tea—Lavinia drank tea). John Gentry seemed to take personal credit for the way St. Louis blossomed just over the eastern horizon of Gentry Farm, and the fact that they could get to St. Louis any day they wanted, on the train from McKittrick, was a source of eternal joy to him (they should have seen the roads, if that was what you wanted to call them, in the Missouri of his youth!). Even so, he went there not more than once in two years.

And then Beatrice was suddenly eighteen years old, a finished product. She could play any number of pieces on the piano, from “Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair” and “Camptown Races” to “Rosalie, the Prairie Flower,” and some more complex pieces without lyrics, such as “Annie and I,” which had three sharps. She could sing if the song in question fell into her range. Her tone was rich and melodious. The time had come to put her on display. A lady Lavinia knew in town had a very nice piano, much nicer than the Gentry piano, which she herself could not play, so, on days when John Gentry had to take a wagon into town anyway for business, he would carry Beatrice along and leave her at Mrs. Larimer’s house on Pennsylvania Street, and Beatrice would play for her. Sometimes, with enough notice, Mrs. Larimer would invite a few friends in to have tea while Beatrice was playing.

The summer Beatrice was eighteen, the cousin of a friend of Mrs. Larimer, a man named Robert Bell, took over the town newspaper. He had money and credentials. What John Gentry knew about Robert Bell, within the first week, was that he was backed by some family capital, he was ambitious, and he had grown up in St. Louis in a big house on Kingshighway, a very wealthy and forward-looking neighborhood.

It was Robert Bell who decreed, young man though he was and new to town, that the Unionists would march at the front of the Fourth of July parade just behind the band; the farm-produce displays, the fire engine, the horse drill, and the mules would march in the middle; and the Rebels (numbering eight by now), dressed in their old Confederate uniforms, would march at the back, behind the Ladies’ Aid Society and the German-American Betterment Society (which dressed in traditional Bavarian costume). He wrote about his plan in the newspaper, alternating discussions of the controversy with news of the war in Cuba, Guam, Puerto Rico, and then the Philippines, until everyone in town had had their say and gotten bored with the War Between the States, especially since the new war seemed to be going so well. According to John Gentry, this strategy of promoting patriotism over infighting was a mark of genius in such a young man, and he went by the office of the newspaper to tell Robert Bell as much. The young man thereupon invited John Gentry and his family to watch the parade from the windows of the newspaper office, which was closed for the afternoon.

To Margaret, Robert Bell was a disappointing sight. He had enormous muttonchop whiskers that only partly disguised his receding chin. His hair was thin and flyaway. His eyes were his best feature, rich blue and much more expressive than his words. He was nicely dressed. But he was considerably shorter than Beatrice—the top of his head came only to the middle of her ear. He made Margaret feel awkward just by standing next to her. He was attentive to them, though. He showed Lavinia to the best chair, which was pulled up right in front of a large open window looking out on Front Street, and then he showed Beatrice to the chair beside that one, and he brought her a cake and a cup of tea. Elizabeth and Margaret he left to fend for themselves, but he had gotten in nice cakes—light, with raspberry filling and marzipan icing, something Margaret had never seen before that day. He also had gotten in enough lemons for real lemonade, which he served with ice. He was comfortable with luxury, just what you would expect in a Bell from St. Louis—Margaret could see this thought passing from Lavinia to her grandfather when they caught each other’s eye and raised an appreciative eyebrow.

Descriere

Descriere de la o altă ediție sau format:

This riveting novel from a Pulitzer Prize winner traverses the intimate landscape of one woman's life, from the 1880s to World War II.

This riveting novel from a Pulitzer Prize winner traverses the intimate landscape of one woman's life, from the 1880s to World War II.