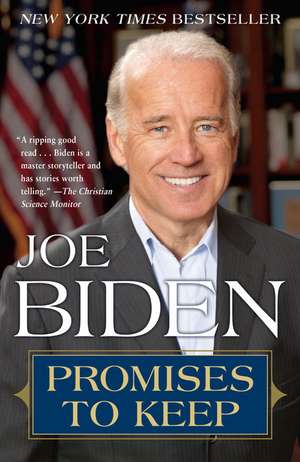

Promises to Keep: On Life and Politics

Autor Joe Bidenen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2008

–Joe Biden

As a United States senator from Delaware since 1973, Joe Biden has been an intimate witness to the major events of the past four decades and a relentless actor in trying to shape recent American history. He has seen up close the tragic mistake of the Vietnam War, the Watergate and Iran-contra scandals, the fall of the Berlin Wall, the reunification of Germany, the disintegration of the Soviet Union, the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, a presidential impeachment, a presidential resignation, and a presidential election decided by the Supreme Court. He’s observed Nixon, Ford, Carter, Reagan, Clinton, and two Bushes wrestling with the presidency; he’s traveled to war zones in Europe, the Middle East, and Africa and seen firsthand the devastation of genocide. He played a vital role by standing up to Ronald Reagan’s effort to seat Judge Robert Bork on the Supreme Court, fighting for legislation that protects women against domestic violence, and galvanizing America’s response (and the world’s) to Slobodan Milosevic’s genocidal march in the Balkans. In Promises to Keep, Biden reveals what these experiences taught him about himself, his colleagues, and the institutions of government.

With his customary candor, Biden movingly recounts growing up in a staunchly Catholic multigenerational household in Scranton, Pennsylvania, and Wilmington, Delaware; overcoming a demoralizing stutter; marriage, fatherhood, and the tragic death of his wife Neilia and infant daughter Naomi; remarriage and re-forming a family with his second wife, Jill; success and failure in the Senate and on the campaign trail; two life-threatening aneurysms; his relations with fellow lawmakers on both sides of the aisle; and his leadership of powerful Senate committees.

Through these and other recollections, Biden shows us how the guiding principles he learned early in life–the obligation to work to make people’s lives better, to honor family and faith, to get up and do the right thing no matter how hard you’ve been knocked down, to be honest and straightforward, and, above all, to keep your promises–are the foundations on which he has based his life’s work as husband, father, and public servant.

Promises to Keep is the story of a man who faced down personal challenges and tragedy to become one of our most effective leaders. It is also an intimate series of reflections from a public servant who refuses to be cynical about political leadership, and a testament to the promise of the United States.

From the Hardcover edition.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 64.64 lei 3-5 săpt. | +13.16 lei 7-13 zile |

| Scribe Publications – 14 ian 2021 | 64.64 lei 3-5 săpt. | +13.16 lei 7-13 zile |

| Random House Trade – 31 iul 2008 | 98.78 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 98.78 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 148

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.90€ • 20.21$ • 15.76£

18.90€ • 20.21$ • 15.76£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 27 martie-10 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780812976212

ISBN-10: 0812976215

Pagini: 365

Ilustrații: 8-PP B/W PHOTO INSERT

Dimensiuni: 130 x 198 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

ISBN-10: 0812976215

Pagini: 365

Ilustrații: 8-PP B/W PHOTO INSERT

Dimensiuni: 130 x 198 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

Notă biografică

Joe Biden was first elected to the United States Senate in 1972 at the age of twenty-nine and is recognized as one of the nation’s most powerful and influential voices on foreign relations, terrorism, drug policy, and crime prevention. Senator Biden grew up in New Castle County, Delaware, and graduated from the University of Delaware and the Syracuse University College of Law. Since 1991, Biden has been an adjunct professor at the Widener University School of Law, where he teaches a seminar on constitutional law. He lives in Wilmington, Delaware.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter 1- Impedimenta

Joe Impedimenta. My classmates hung that nickname on me our first semester of high school when we were doing two periods of Latin a day. It was one of the first big words we learned. Impedimenta—the baggage that impedes one’s progress. So I was Joe Impedimenta. Or Dash. A lot of people thought they called me Dash because of football. I was fast, and I scored my share of touchdowns. But the guys at an all-boys Catholic school usually didn’t give you nicknames to make you feel better about yourself. They didn’t call me Dash because of what I could do on the football field; they called me Dash because of what I could not do in the classroom. I talked like Morse code. Dot-dot-dot-dot-dash-dash-dash-dash. “You gu-gu-gu-gu-guys sh-sh-sh-sh-shut up!”

My impedimenta was a stutter. It wasn’t always bad. When I was at home with my brothers and sister, hanging out with my neighborhood friends, or shooting the bull on the ball field, I was fine, but when I got thrown into a new situation or a new school, had to read in front of the class, or wanted to ask out a girl, I just couldn’t do it. My freshman year of high school, because of the stutter, I got an exemption from public speaking. Everybody else had to get up and make a presentation at the morning assembly, in front of 250 boys. I got a pass. And everybody knew it. Maybe they didn’t think much of it—they had other things to worry about—but I did. It was like having to stand in the corner with the dunce cap. Other kids looked at me like I was stupid. They laughed. I wanted so badly to prove I was like everybody else. Even today I can remember the dread, the shame, the absolute rage, as vividly as the day it was happening. There were times I thought it was the end of the world, my impedimenta. I worried that the stutter was going to be my epitaph. And there were days I wondered: How would I ever beat it?

It’s a funny thing to say, but even if I could, I wouldn’t wish away the darkest days of the stutter. That impedimenta ended up being a godsend for me. Carrying it strengthened me and, I hoped, made me a better person. And the very things it taught me turned out to be invaluable lessons for my life as well as my chosen career.

I started worrying about my stutter back in Scranton, Pennsylvania, in grade school. When I was in kindergarten, my parents sent me to a speech pathologist at Marywood College, but it didn’t help much, so I went only a few times. Truth was, I didn’t let the stutter get in the way of things that really mattered to me. I was young for my grade and always little for my age, but I made up for it by demonstrating I had guts. On a dare, I’d climb to the top of a burning culm dump, swing out over a construction site, race under a moving dump truck. If I could visualize myself doing it, I knew I could do it. It never crossed my mind that I couldn’t. As much as I lacked confidence in my ability to communicate verbally, I always had confidence in my athletic ability. Sports was as natural to me as speaking was unnatural. And sports turned out to be my ticket to acceptance—and more. I wasn’t easily intimidated in a game, so even when I stuttered, I was always the kid who said, “Give me the ball.”

Who’s going to take the last shot? “Give me the ball.” We need a touchdown now. “Give me the ball.” I’d be eight years old, usually the smallest guy on the field, but I wanted the ball. And they gave it to me.

When I was ten, we moved from the Scranton neighborhood I knew so well to Wilmington, Delaware. My dad was having trouble finding a good job in Scranton, and his brother Frank kept telling him there were jobs in Wilmington. The Biden brothers had spent most of their school days in Wilmington, so it was like going home for my dad. For the rest of us, it felt like leaving home. But my mom, who was born and raised in Scranton, determined to see it as my dad did; she refused to see it any other way. This was a wonderful opportunity. We’d have a fresh start. We’d make new friends. We were moving into a brand-new neighborhood, to a brand-new home. This wasn’t a hand-me-down house. We’d be the first people to ever set foot in it. It was all good. She was like that with my stutter, too. She wouldn’t dwell on the bad stuff. Joey, you’re so handsome. Joey, you’re such a good athlete. Joey, you’ve got such a high IQ. You’ve got so much to say, honey, that your brain gets ahead of you. And if the other kids made fun of me, well, that was their problem. They’re just jealous.

She knew how wounding kids could be. One thing she determined to do when we moved to Wilmington was hold me back a year. Besides being young and small, I’d missed a lot of school the last year in Scranton when I’d had my tonsils and adenoids removed. So when we got to Wilmington, my mom insisted I do third grade over—and none of the kids at Holy Rosary had to know I was being held back by my mom. That was just another of the ways Wilmington would be a fresh start.

Actually, we were moving to the outskirts of Wilmington, to a working-class neighborhood called the Claymont area, just across the Pennsylvania state line. I still remember the drive into Delaware. It all felt like an adventure. My dad was at the wheel and my mom was up front with him, with the three of us kids in back: me, my brother, Jimmy, and my six-year-old sister, Valerie, who was also my best friend. We drove across the state line on the Philadelphia Turnpike, past the Worth Steel Mill, the General Chemical Company, and the oil refineries, all spewing smoke. We drove past Worthland and Overlook Colony, tightly packed with the row houses that the mills had built for their workers not long after the turn of the century. Worthland was full of Italians and Poles; Overlook Colony was black. It was just a mile or so down the road to Brookview Apartments and our brand-new garden unit. A right off the Philadelphia Pike, and we were home.

Brookview was a moonscape. A huge water tower loomed over the development, but there wasn’t a tree in sight. We followed the main road in as it swept us in a gentle curve. Off the main road were the “courts.” One side was built, but the other was still under construction. We could see the heavy machinery idling among the mounds of dirt and red clay. It was a hot summer day, so our car windows were rolled down. I can still remember the smell of that red clay, the sulfurous stink from the bowels of the earth. As we arced down the main street toward a new home, my mom caught sight of these airless little one-story apartments. They were the color of brown mustard. My dad must have seen my mom’s face as she scanned her new neighborhood. “Don’t worry, Pudd’,” he told her. “It’s not these. We have a big one.”

He pulled the car around to the bottom of a bend, and without getting out of the car, he pointed across an expanse of not-quite lawn, toward the big one. Our new home was a two-story unit, white, with thin columns in front—a hint of Tara, I guess—and a one-story box off each side. “There it is,” he said.

“All of this?” Mom asked.

“No, just the center,” my dad said. Then, “Don’t worry, Pudd’, it’s only temporary.”

From the backseat I could tell my mom was crying.

“Mom!? What’s the matter, Mommy?”

“I’m just so happy. Isn’t it beautiful? Isn’t it beautiful?”

Actually, it didn’t seem bad to me. It was a miniature version of a center hall colonial, and we had bedrooms upstairs. I had the bedroom in back, which meant from my window I could gaze upon the object of my deepest desire, my Oz: Archmere. Right in the middle of this working-class steel town, not a mile from the mills and directly across from the entrance of Brookview Apartments, was the first mansion I had ever really seen. I could look at it for hours. John Jacob Raskob had built the house for his family before the steel mills, chemical plants, and oil refineries came to Claymont. Raskob was Pierre du Pont’s personal secretary, but he had a genius for making money out of money. He convinced the du Ponts to take a big stake in General Motors and became its chairman of finance. Raskob was also a Catholic hero. He used part of his fortune to fund a charitable foundation, and he’d run the campaign of the first Catholic presidential nominee, the Democrat Al Smith. In 1928 the Democrats had political strategy sessions in his library at Archmere. Raskob went on to build the Empire State Building.

The mansion he built in Claymont, the Patio at Archmere, was a magnificent Italianate marble pile on a property that sloped down to the Delaware River. Archmere—arch by the sea—was named for the arch of elms that ran on that slope to the river. But after the working man’s families, not to mention the noise and pollution from the mills, began to crowd the Patio, Raskob cut his losses and sold the mansion to an order of Catholic priests. The Norbertines turned it into a private boys’ school. Archmere Academy was just twenty years old when I moved in across the street.

When I played CYO football that year, our coach was Dr. Anzelotti, a Ph.D. chemist at DuPont who had sons at the school. Archmere let Dr. Anzelotti run our practices on the grounds of the school. From the moment I got within the ten-foot-high wrought-iron fence that surrounded the campus and drove up the road—they actually called it the yellow-brick road—I knew where I wanted to go to high school. I didn’t ever think of Archmere as a path to greater glory. When I was ten, getting to Archmere seemed enough. I’d sit and stare out my bedroom window and dream of the day I would walk through the front doors and take my spot in that seat of learning. I’d dream of the day I would score the touchdown or hit the game-winning home run.

I entered third grade at Holy Rosary, a Catholic school half a mile down the Philadelphia Pike where the Sisters of Saint Joseph eased me into my new world. They were the link between Scranton and Claymont. Wherever there were nuns, there was home. I’m as much a cultural Catholic as I am a theological Catholic. My idea of self, of family, of community, of the wider world comes straight from my religion. It’s not so much the Bible, the beatitudes, the Ten Commandments, the sacraments, or the prayers I learned. It’s the culture. The nuns are one of the reasons I’m still a practicing Catholic. Last summer in Dubuque, Iowa, a local political ally, Teri Goodmann, took me to the Saint Francis Convent—a beautiful old building that looked like it belonged on an Ivy League campus. On the way over we’d stopped by the Hy-Vee to buy some ice cream for the sisters, because Jean Finnegan Biden’s son does not visit nuns empty-handed. It reminded me of grade school, of the last day before the holidays when all my classmates would be presenting their little Christmas offerings to the nun. The desk would be a mound of little specialty soaps. (What else do you get a nun?) The sisters smelled like lavender the rest of the year. I don’t remember a nun not smelling like lavender.

So I walked into the Dubuque convent with several gallons of ice cream and immediately began to worry we hadn’t brought enough. Teri was expecting ten or twelve of the sisters to show up for the event, but there must have been four dozen nuns—many of them from the generation that taught me as a boy—sitting in a community room. I was there to give a talk about the situation in Iraq, and the sisters really wanted to understand the sectarian conflict there. They peppered me with questions about the Sunnis, the Shi’ites, and the Kurds. They wanted to know about the history of the religion the Kurds practice, and they wanted to know how I educated myself about the concerns of the Iraqi people. Many of these nuns had been teachers; knowledge mattered most. We also talked about our own church, then about women’s issues, education, and national security. Whether they agreed with my public positions or not, they all smiled at me. Even after we opened up the ice cream, they kept asking questions. And as I was getting ready to leave Teri asked if the sisters would, in the days ahead, pray for Joe Biden’s success in his public journey. But they did more than that. The sisters formed a circle around me, raised their arms up over my head, and started singing the blessing they give to one of their own who is going off to do God’s work in the next place. “May God bless you and keep you.” The sisters were so sweet and so genuine that it made me feel the way I did when I was a kid, like I was in touch with something bigger than me. It wasn’t any epiphany, wasn’t any altar call. It was where I’ve always been. The Sisters of Saint Francis in Dubuque, Iowa, were taking me home.

The nuns were my first teachers. At Holy Rosary, like at Saint Paul’s in Scranton, they taught reading and writing and math and geography and history, but embedded in the curriculum also were the concepts of decency, fair play, and virtue. They took as a starting point the biblical exhortation that man has no greater love than to lay down his life for another man; in school we were about ten clicks back from that. You didn’t give your life, but it was noble to help a lady across the street. It was noble to offer a hand up to somebody who had less. It was noble to step in when the bully was picking on somebody. It was noble to intervene.

From the Hardcover edition.

Joe Impedimenta. My classmates hung that nickname on me our first semester of high school when we were doing two periods of Latin a day. It was one of the first big words we learned. Impedimenta—the baggage that impedes one’s progress. So I was Joe Impedimenta. Or Dash. A lot of people thought they called me Dash because of football. I was fast, and I scored my share of touchdowns. But the guys at an all-boys Catholic school usually didn’t give you nicknames to make you feel better about yourself. They didn’t call me Dash because of what I could do on the football field; they called me Dash because of what I could not do in the classroom. I talked like Morse code. Dot-dot-dot-dot-dash-dash-dash-dash. “You gu-gu-gu-gu-guys sh-sh-sh-sh-shut up!”

My impedimenta was a stutter. It wasn’t always bad. When I was at home with my brothers and sister, hanging out with my neighborhood friends, or shooting the bull on the ball field, I was fine, but when I got thrown into a new situation or a new school, had to read in front of the class, or wanted to ask out a girl, I just couldn’t do it. My freshman year of high school, because of the stutter, I got an exemption from public speaking. Everybody else had to get up and make a presentation at the morning assembly, in front of 250 boys. I got a pass. And everybody knew it. Maybe they didn’t think much of it—they had other things to worry about—but I did. It was like having to stand in the corner with the dunce cap. Other kids looked at me like I was stupid. They laughed. I wanted so badly to prove I was like everybody else. Even today I can remember the dread, the shame, the absolute rage, as vividly as the day it was happening. There were times I thought it was the end of the world, my impedimenta. I worried that the stutter was going to be my epitaph. And there were days I wondered: How would I ever beat it?

It’s a funny thing to say, but even if I could, I wouldn’t wish away the darkest days of the stutter. That impedimenta ended up being a godsend for me. Carrying it strengthened me and, I hoped, made me a better person. And the very things it taught me turned out to be invaluable lessons for my life as well as my chosen career.

I started worrying about my stutter back in Scranton, Pennsylvania, in grade school. When I was in kindergarten, my parents sent me to a speech pathologist at Marywood College, but it didn’t help much, so I went only a few times. Truth was, I didn’t let the stutter get in the way of things that really mattered to me. I was young for my grade and always little for my age, but I made up for it by demonstrating I had guts. On a dare, I’d climb to the top of a burning culm dump, swing out over a construction site, race under a moving dump truck. If I could visualize myself doing it, I knew I could do it. It never crossed my mind that I couldn’t. As much as I lacked confidence in my ability to communicate verbally, I always had confidence in my athletic ability. Sports was as natural to me as speaking was unnatural. And sports turned out to be my ticket to acceptance—and more. I wasn’t easily intimidated in a game, so even when I stuttered, I was always the kid who said, “Give me the ball.”

Who’s going to take the last shot? “Give me the ball.” We need a touchdown now. “Give me the ball.” I’d be eight years old, usually the smallest guy on the field, but I wanted the ball. And they gave it to me.

When I was ten, we moved from the Scranton neighborhood I knew so well to Wilmington, Delaware. My dad was having trouble finding a good job in Scranton, and his brother Frank kept telling him there were jobs in Wilmington. The Biden brothers had spent most of their school days in Wilmington, so it was like going home for my dad. For the rest of us, it felt like leaving home. But my mom, who was born and raised in Scranton, determined to see it as my dad did; she refused to see it any other way. This was a wonderful opportunity. We’d have a fresh start. We’d make new friends. We were moving into a brand-new neighborhood, to a brand-new home. This wasn’t a hand-me-down house. We’d be the first people to ever set foot in it. It was all good. She was like that with my stutter, too. She wouldn’t dwell on the bad stuff. Joey, you’re so handsome. Joey, you’re such a good athlete. Joey, you’ve got such a high IQ. You’ve got so much to say, honey, that your brain gets ahead of you. And if the other kids made fun of me, well, that was their problem. They’re just jealous.

She knew how wounding kids could be. One thing she determined to do when we moved to Wilmington was hold me back a year. Besides being young and small, I’d missed a lot of school the last year in Scranton when I’d had my tonsils and adenoids removed. So when we got to Wilmington, my mom insisted I do third grade over—and none of the kids at Holy Rosary had to know I was being held back by my mom. That was just another of the ways Wilmington would be a fresh start.

Actually, we were moving to the outskirts of Wilmington, to a working-class neighborhood called the Claymont area, just across the Pennsylvania state line. I still remember the drive into Delaware. It all felt like an adventure. My dad was at the wheel and my mom was up front with him, with the three of us kids in back: me, my brother, Jimmy, and my six-year-old sister, Valerie, who was also my best friend. We drove across the state line on the Philadelphia Turnpike, past the Worth Steel Mill, the General Chemical Company, and the oil refineries, all spewing smoke. We drove past Worthland and Overlook Colony, tightly packed with the row houses that the mills had built for their workers not long after the turn of the century. Worthland was full of Italians and Poles; Overlook Colony was black. It was just a mile or so down the road to Brookview Apartments and our brand-new garden unit. A right off the Philadelphia Pike, and we were home.

Brookview was a moonscape. A huge water tower loomed over the development, but there wasn’t a tree in sight. We followed the main road in as it swept us in a gentle curve. Off the main road were the “courts.” One side was built, but the other was still under construction. We could see the heavy machinery idling among the mounds of dirt and red clay. It was a hot summer day, so our car windows were rolled down. I can still remember the smell of that red clay, the sulfurous stink from the bowels of the earth. As we arced down the main street toward a new home, my mom caught sight of these airless little one-story apartments. They were the color of brown mustard. My dad must have seen my mom’s face as she scanned her new neighborhood. “Don’t worry, Pudd’,” he told her. “It’s not these. We have a big one.”

He pulled the car around to the bottom of a bend, and without getting out of the car, he pointed across an expanse of not-quite lawn, toward the big one. Our new home was a two-story unit, white, with thin columns in front—a hint of Tara, I guess—and a one-story box off each side. “There it is,” he said.

“All of this?” Mom asked.

“No, just the center,” my dad said. Then, “Don’t worry, Pudd’, it’s only temporary.”

From the backseat I could tell my mom was crying.

“Mom!? What’s the matter, Mommy?”

“I’m just so happy. Isn’t it beautiful? Isn’t it beautiful?”

Actually, it didn’t seem bad to me. It was a miniature version of a center hall colonial, and we had bedrooms upstairs. I had the bedroom in back, which meant from my window I could gaze upon the object of my deepest desire, my Oz: Archmere. Right in the middle of this working-class steel town, not a mile from the mills and directly across from the entrance of Brookview Apartments, was the first mansion I had ever really seen. I could look at it for hours. John Jacob Raskob had built the house for his family before the steel mills, chemical plants, and oil refineries came to Claymont. Raskob was Pierre du Pont’s personal secretary, but he had a genius for making money out of money. He convinced the du Ponts to take a big stake in General Motors and became its chairman of finance. Raskob was also a Catholic hero. He used part of his fortune to fund a charitable foundation, and he’d run the campaign of the first Catholic presidential nominee, the Democrat Al Smith. In 1928 the Democrats had political strategy sessions in his library at Archmere. Raskob went on to build the Empire State Building.

The mansion he built in Claymont, the Patio at Archmere, was a magnificent Italianate marble pile on a property that sloped down to the Delaware River. Archmere—arch by the sea—was named for the arch of elms that ran on that slope to the river. But after the working man’s families, not to mention the noise and pollution from the mills, began to crowd the Patio, Raskob cut his losses and sold the mansion to an order of Catholic priests. The Norbertines turned it into a private boys’ school. Archmere Academy was just twenty years old when I moved in across the street.

When I played CYO football that year, our coach was Dr. Anzelotti, a Ph.D. chemist at DuPont who had sons at the school. Archmere let Dr. Anzelotti run our practices on the grounds of the school. From the moment I got within the ten-foot-high wrought-iron fence that surrounded the campus and drove up the road—they actually called it the yellow-brick road—I knew where I wanted to go to high school. I didn’t ever think of Archmere as a path to greater glory. When I was ten, getting to Archmere seemed enough. I’d sit and stare out my bedroom window and dream of the day I would walk through the front doors and take my spot in that seat of learning. I’d dream of the day I would score the touchdown or hit the game-winning home run.

I entered third grade at Holy Rosary, a Catholic school half a mile down the Philadelphia Pike where the Sisters of Saint Joseph eased me into my new world. They were the link between Scranton and Claymont. Wherever there were nuns, there was home. I’m as much a cultural Catholic as I am a theological Catholic. My idea of self, of family, of community, of the wider world comes straight from my religion. It’s not so much the Bible, the beatitudes, the Ten Commandments, the sacraments, or the prayers I learned. It’s the culture. The nuns are one of the reasons I’m still a practicing Catholic. Last summer in Dubuque, Iowa, a local political ally, Teri Goodmann, took me to the Saint Francis Convent—a beautiful old building that looked like it belonged on an Ivy League campus. On the way over we’d stopped by the Hy-Vee to buy some ice cream for the sisters, because Jean Finnegan Biden’s son does not visit nuns empty-handed. It reminded me of grade school, of the last day before the holidays when all my classmates would be presenting their little Christmas offerings to the nun. The desk would be a mound of little specialty soaps. (What else do you get a nun?) The sisters smelled like lavender the rest of the year. I don’t remember a nun not smelling like lavender.

So I walked into the Dubuque convent with several gallons of ice cream and immediately began to worry we hadn’t brought enough. Teri was expecting ten or twelve of the sisters to show up for the event, but there must have been four dozen nuns—many of them from the generation that taught me as a boy—sitting in a community room. I was there to give a talk about the situation in Iraq, and the sisters really wanted to understand the sectarian conflict there. They peppered me with questions about the Sunnis, the Shi’ites, and the Kurds. They wanted to know about the history of the religion the Kurds practice, and they wanted to know how I educated myself about the concerns of the Iraqi people. Many of these nuns had been teachers; knowledge mattered most. We also talked about our own church, then about women’s issues, education, and national security. Whether they agreed with my public positions or not, they all smiled at me. Even after we opened up the ice cream, they kept asking questions. And as I was getting ready to leave Teri asked if the sisters would, in the days ahead, pray for Joe Biden’s success in his public journey. But they did more than that. The sisters formed a circle around me, raised their arms up over my head, and started singing the blessing they give to one of their own who is going off to do God’s work in the next place. “May God bless you and keep you.” The sisters were so sweet and so genuine that it made me feel the way I did when I was a kid, like I was in touch with something bigger than me. It wasn’t any epiphany, wasn’t any altar call. It was where I’ve always been. The Sisters of Saint Francis in Dubuque, Iowa, were taking me home.

The nuns were my first teachers. At Holy Rosary, like at Saint Paul’s in Scranton, they taught reading and writing and math and geography and history, but embedded in the curriculum also were the concepts of decency, fair play, and virtue. They took as a starting point the biblical exhortation that man has no greater love than to lay down his life for another man; in school we were about ten clicks back from that. You didn’t give your life, but it was noble to help a lady across the street. It was noble to offer a hand up to somebody who had less. It was noble to step in when the bully was picking on somebody. It was noble to intervene.

From the Hardcover edition.