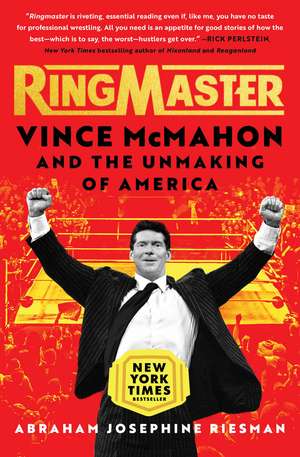

Ringmaster: Vince McMahon and the Unmaking of America

Autor Abraham Josephine Riesmanen Limba Engleză Paperback – 23 mai 2024

Even if you’ve never watched a minute of professional wrestling, you are living in Vince McMahon’s world.

In his four decades as the defining figure of American pro wrestling, McMahon was the man behind Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, “Stone Cold” Steve Austin, John Cena, Dave Bautista, Bret “The Hitman” Hart, and Hulk Hogan, to name just a few of the mega-stars who owe him their careers. For more than twenty-five years, he has also been a performer in his own show, acting as the diabolical “Mr. McMahon”—a figure who may have more in common with the real Vince than he would care to admit.

Just as importantly, McMahon is one of Donald Trump’s closest friends—and Trump’s experiences as a performer in McMahon’s programming were, in many ways, a dress rehearsal for the 45th President’s campaigns and presidency. McMahon and his wife, Linda, are major Republican donors. Linda was in Trump’s cabinet. McMahon makes deals with the Saudi government worth hundreds of millions of dollars. And for generations of people who have watched wrestling, he has been a defining cultural force and has helped foment “the worst of contemporary politics” (Kirkus Reviews).

Ringmaster built on exclusive interviews with more than 150 people, from McMahon’s childhood friends to those who accuse him of destroying their lives. “Smart, entertaining, impressively reported, and beautifully written. Wrestling fans will devour it, but everyone who wants to better understand this crazy country and one of its truly original characters ought to read it” (Jonathan Eig, author of Ali: A Life).

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (1) | 58.58 lei 25-37 zile | +27.96 lei 4-10 zile |

| ATRIA – 23 mai 2024 | 58.58 lei 25-37 zile | +27.96 lei 4-10 zile |

| Hardback (1) | 124.09 lei 3-5 săpt. | +29.51 lei 4-10 zile |

| ATRIA – 21 iun 2023 | 124.09 lei 3-5 săpt. | +29.51 lei 4-10 zile |

Preț: 58.58 lei

Preț vechi: 71.31 lei

-18% Nou

Puncte Express: 88

Preț estimativ în valută:

11.21€ • 12.18$ • 9.42£

11.21€ • 12.18$ • 9.42£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 04-16 aprilie

Livrare express 14-20 martie pentru 37.95 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781982169459

ISBN-10: 1982169451

Pagini: 496

Ilustrații: b&w chapter openers

Dimensiuni: 140 x 213 x 30 mm

Greutate: 0.37 kg

Editura: ATRIA

Colecția Atria Books

ISBN-10: 1982169451

Pagini: 496

Ilustrații: b&w chapter openers

Dimensiuni: 140 x 213 x 30 mm

Greutate: 0.37 kg

Editura: ATRIA

Colecția Atria Books

Notă biografică

Abraham Josephine Riesman is a journalist and essayist, as well as the author of the biographies Ringmaster: Vince McMahon and the Unmaking of America and True Believer: The Rise and Fall of Stan Lee. She was a longtime staffer at New York magazine and its culture site, Vulture, and her work has also appeared in The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, The Boston Globe, VICE, The New Republic, and elsewhere. She lives in Providence, Rhode Island, with her spouse and their cats.

Recenzii

“MAGISTERIAL.” —The New York Times

“This revelatory biography of Vince McMahon argues convincingly that pro wrestling can explain contemporary America. It’s a knockout.”

—Publishers Weekly, Starred review

"Ringmaster is riveting, essential reading even if, like me, you have no taste for professional wrestling. All you need is an appetite for good stories of how the best—which is to say, the worst—conmen get over. Follow Abraham Riesman through that looking glass, and you even may creep closer to understanding how the U.S. managed to make one president."—Rick Perlstein, New York Times bestselling author of Nixonland and Reaganland

“If you’re vaguely interested in a ludicrously buff mogul who booked himself to beat God in a wrestling match, or just interested in the definitive book on America’s last truly riveting carny showman, this is a story that forces you to turn the page. But this book isn’t just about Vince McMahon, the ringmaster. It’s about his circus of abused elephants, magicians, musclemen dipped in bleach, and acrobats who fall to their death, a “family business” which turned into the bloodiest version of Succession.”—The Spectator

“A vivid, warts-and-all portrait of the man behind WrestleMania—and much of the worst of contemporary politics.”—Kirkus

"RINGMASTER examines how seemingly innocuous pastimes like professional wrestling have shaped American culture and warped it beyond measure. In Abraham Riesman's telling, Vince McMahon emerges as a powerful figure of terrifying complexity, his rise and fall in lockstep with the country's. RINGMASTER brilliantly pulls back the curtain of kayfabe to reveal the pulsating reality underneath—and how the lines, once blurred, can never be separated again."—Sarah Weinman, bestselling author of The Real Lolita and Scoundrel

“To understand what's at the heart of carny culture is to understand what's at the heart of a huge swath of the American experience. As Abraham Riesman demonstrates in this highly readable, sharp and compelling book, professional wrestling embodies this idea both on screen and off, in the arenas and in the conference rooms. This is a serious work about the legacy of confidence games, abandonment, abuse and power. Whether or not you are a lifelong wrestling mark like me, Ringmaster is essential reading.”—Brian Koppelman, cocreator of Billions and cowriter of Rounders

"No faking! Ringmaster is one of the best biographies I’ve read in years — smart, entertaining, impressively reported, and beautifully written. Wrestling fans will devour it, but everyone who wants to better understand this crazy country and one of its truly original characters ought to read it." —Jonathan Eig, author of Ali: A Life

"Abraham Riesman has given us a fascinating, rigorously researched account of the life and times of the ultimate ringmaster, Vince McMahon. This is the story of how the world of professional wrestling has become our world. The rules of the game are now so gamed in American politics and daily life that the real, if ever there was a real, has gone up in a puff of hyperbolic smoke-and-mirrors. Ringmaster helps us to see how we got to this point. How we get ourselves out of it remains an open question." —Sharon Mazer, author of Professional Wrestling: Sport and Spectacle

"Though it's hard to pinpoint the date, one morning wrestling fans like myself woke up and realized the pastime that had largely defined our youths and imaginations had jumped the firewall and, somehow, some way, began infecting the rest of the world. What Abraham Riesman has done here is invite readers to see that fundamental and disturbing truth, to wrestle with just how we've come to live in this bizarre un-reality, and possibly begin sorting through the wreckage. An absolute triumph. As must-read as must-read can get." —Jared Yates Sexton, author of The Midnight Kingdom: A History of Power, Paranoia, and the Coming Crisis

“This revelatory biography of Vince McMahon argues convincingly that pro wrestling can explain contemporary America. It’s a knockout.”

—Publishers Weekly, Starred review

"Ringmaster is riveting, essential reading even if, like me, you have no taste for professional wrestling. All you need is an appetite for good stories of how the best—which is to say, the worst—conmen get over. Follow Abraham Riesman through that looking glass, and you even may creep closer to understanding how the U.S. managed to make one president."—Rick Perlstein, New York Times bestselling author of Nixonland and Reaganland

“If you’re vaguely interested in a ludicrously buff mogul who booked himself to beat God in a wrestling match, or just interested in the definitive book on America’s last truly riveting carny showman, this is a story that forces you to turn the page. But this book isn’t just about Vince McMahon, the ringmaster. It’s about his circus of abused elephants, magicians, musclemen dipped in bleach, and acrobats who fall to their death, a “family business” which turned into the bloodiest version of Succession.”—The Spectator

“A vivid, warts-and-all portrait of the man behind WrestleMania—and much of the worst of contemporary politics.”—Kirkus

"RINGMASTER examines how seemingly innocuous pastimes like professional wrestling have shaped American culture and warped it beyond measure. In Abraham Riesman's telling, Vince McMahon emerges as a powerful figure of terrifying complexity, his rise and fall in lockstep with the country's. RINGMASTER brilliantly pulls back the curtain of kayfabe to reveal the pulsating reality underneath—and how the lines, once blurred, can never be separated again."—Sarah Weinman, bestselling author of The Real Lolita and Scoundrel

“To understand what's at the heart of carny culture is to understand what's at the heart of a huge swath of the American experience. As Abraham Riesman demonstrates in this highly readable, sharp and compelling book, professional wrestling embodies this idea both on screen and off, in the arenas and in the conference rooms. This is a serious work about the legacy of confidence games, abandonment, abuse and power. Whether or not you are a lifelong wrestling mark like me, Ringmaster is essential reading.”—Brian Koppelman, cocreator of Billions and cowriter of Rounders

"No faking! Ringmaster is one of the best biographies I’ve read in years — smart, entertaining, impressively reported, and beautifully written. Wrestling fans will devour it, but everyone who wants to better understand this crazy country and one of its truly original characters ought to read it." —Jonathan Eig, author of Ali: A Life

"Abraham Riesman has given us a fascinating, rigorously researched account of the life and times of the ultimate ringmaster, Vince McMahon. This is the story of how the world of professional wrestling has become our world. The rules of the game are now so gamed in American politics and daily life that the real, if ever there was a real, has gone up in a puff of hyperbolic smoke-and-mirrors. Ringmaster helps us to see how we got to this point. How we get ourselves out of it remains an open question." —Sharon Mazer, author of Professional Wrestling: Sport and Spectacle

"Though it's hard to pinpoint the date, one morning wrestling fans like myself woke up and realized the pastime that had largely defined our youths and imaginations had jumped the firewall and, somehow, some way, began infecting the rest of the world. What Abraham Riesman has done here is invite readers to see that fundamental and disturbing truth, to wrestle with just how we've come to live in this bizarre un-reality, and possibly begin sorting through the wreckage. An absolute triumph. As must-read as must-read can get." —Jared Yates Sexton, author of The Midnight Kingdom: A History of Power, Paranoia, and the Coming Crisis

Descriere

The definitive biography of WWE Chairman and CEO, Vince McMahon, charting his rise from growing up as a dyslexic boy in a trailer park to the iconoclastic leader of a multi-billion-dollar empire, with new reporting and exclusive interviews from those witnessed, aided, and suffered from his ascent.

Extras

Chapter 1: Fall (1945–1957)

Vince McMahon, like many of his wrestlers, didn’t grow up with the name he now uses. His father ran a successful wrestling promotion that stretched throughout the Northeast, but Vince was born and raised far away from that empire. He wasn’t even a wrestling fan as a child. WWE has often highlighted the boss’s adoration for the man everyone now calls “Vince Senior.” But until young Vince was an adolescent, he’d never met the man. He was Vinnie Lupton, and he didn’t know if he loved his dad or not.

In his formative years, Vinnie was the son of two people of whom he rarely speaks: Vicki Hanner and Leo Lupton Jr.—his mother and stepfather.

Which is to say, he was a son of North Carolina, however much he may obscure that fact. The sizable Hanner and Lupton clans had been in the state for generations. The Hanners arrived in the colony before it became a founding component of the United States, and by the time of the Civil War, they had settled in as farmers—some of them slaveholders. For example, the most renowned member of Vince’s maternal family prior to him was John Henry Hanner, who, when he died in 1850, held ten people in captivity, making his 614-acre farm (located in what is now Greensboro) one of the area’s larger forced-work camps.

But by the time Victoria Elizabeth Hanner was born in 1920, the family had been in a decades-long decline. Her mother was a farmer’s daughter; her father an itinerant mechanic who rambled back and forth between North and South Carolina, barely making a living while working on automobiles.

Vicki appears to have been born in Florence, South Carolina, and raised in Sanford, North Carolina. She then did a jaunt at Bob Jones College in faraway Cleveland, Tennessee. However, a North Carolina birth index of 1939 informs us that Victoria Hanner—who would have been either eighteen or nineteen at the time—gave birth to a child many miles from both home and school, in Charlotte. In the column for the father’s name, there is only a series of dashes. The baby—Vince’s oldest sibling—was named Gloria Faye Hanner, and there is no record of what became of her.

On December 6, 1941, just a few hours before the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, Vicki married an Ohio-born soldier named Louis Patacca, who was stationed at a nearby military base. That marriage, her first of four, was doomed. Patacca was shipped up to New York City, and Vicki found someone else to occupy her time.

We don’t know how she met Vince’s father, but they may have had their first tryst around June 30, 1942, while New York–based Vincent James McMahon was doing his own military service in Wilmington, North Carolina—a local newspaper item mentions that a visiting “Victoria Patacca” had lost a diamond ring. As of January 1943, Vicki was pregnant with her lover’s child.

Patacca filed a vitriolic divorce petition on August 18, 1943, claiming his estranged wife had withheld the fact of Gloria’s birth from him and had cheated on him with other soldiers. Vicki didn’t respond; the divorce wasn’t resolved as of at least four years later. The military moved Vincent James McMahon back to New York, where his and Vicki’s first child, a boy dubbed Roderick James “Rod” McMahon, was born out of wedlock on October 12.

We do not know what happened between these two young parents for the next eleven months. But we know they got married on September 4, 1944, in South Carolina’s Horry County, where authorities didn’t seem to note that Vicki’s divorce was still pending in the next state over. By the end of November, she was pregnant again.

On August 18, 1945, three days after Japan laid down its arms, Vincent J. McMahon was discharged from the New York base that had been his final station. Vicki was about to give birth in North Carolina.

The couple’s second son entered the world at 7:14 a.m. on August 24, in Pinehurst, North Carolina’s Moore County Hospital. Vicki named the child after its father: Vincent Kennedy McMahon. Kennedy was her mother’s maiden name.

On September 16, young Vince was baptized in a Moore County Catholic church. The Hanners were Presbyterians, but the McMahons were Catholics, so this was probably the last influence the father would have on his son’s life for years.

By the time young Vince was old enough to remember anything, the man was gone.

“You know, I’m not big on excuses,” Vince told an interviewer from Playboy in the latter half of 2000. “When I hear people from the projects, or anywhere else, blame their actions on the way they grew up, I think it’s a crock of shit. You can rise above it.”

The topic of conversation was Vince’s own upbringing. He was talking about being sexually abused as a child.

The reporter pointed out how terrible it must have been for him. Vince bristled. “This country gives you opportunity if you want to take it, so don’t blame your environment,” Vince replied. “I look down on people who use their environment as a crutch.”

The reporter brought up Vince losing his virginity. Vince paused. “That was at a very young age,” he said. “I remember, probably in the first grade, being invited to a matinee film with my stepbrother and his girlfriends, and I remember them playing with me. Playing with my penis, and giggling. I thought that was pretty cool. That was my initiation into sex. At that age you don’t necessarily achieve an erection, but it was cool.”

He also recalled incidents involving a local whom he described as “a girl my age who was, in essence, my cousin”: “I remember the two of us being so curious about each other’s bodies, but not knowing what the hell to do,” Vince said. “We would go into the woods and get naked together. It felt good. And, for some reason, I wanted to put crushed leaves into her.” He told the interviewer he didn’t actually remember when he putatively lost his virginity.

“Your growing-up was pretty accelerated,” the reporter said.

“God, yes,” said Vince.

The interviewer brought up Vince’s childhood family unit. Vince said he lived with his mother “and my real asshole of a stepfather, a man who enjoyed kicking people around.”

“Your stepfather beat you?” the interviewer asked.

Vince’s reply: “Leo Lupton. It’s unfortunate that he died before I could kill him. I would have enjoyed that.”

Leo Hubert Lupton Jr. was born in New Bern, North Carolina, in 1917 and dropped out of high school after his freshman year. He trained as an electrician and married a girl named Peggy Lane in 1939. Their marriage was troubled, to say the least. In May of 1940, Peggy gave birth to their first child, Richard. But scarcely a year later, Leo had been convicted of abandoning his family and was sentenced to “two years on the roads,” according to a brief, cryptic newspaper item. However, a later newspaper item implies he and Peggy were back together three months later, when their daughter, Ernestine—better known as “Teenie”—was born in September of 1941.

Leo’s troubles were compounded upon enlisting in the Navy for service in the Pacific in August of 1944. Although he held the honor of being on a boat that was present in Tokyo Bay when the Japanese instrument of surrender was signed, his wife had a stillbirth while he was at sea. Upon returning to North Carolina, he and Peggy separated, and he held on to the kids. He appears to have moved with them into his parents’ house in the South Carolina town of Mount Pleasant. Vicki’s parents were also living in Mount Pleasant at the time, making it likely that a parental connection was how the couple met.

Vicki filed for divorce from young Vinnie’s father on grounds of desertion, but in a curious way: she filed in faraway Leon County, Florida, the region in the Panhandle that contains Tallahassee, and her listed residence was in Lakeland, Florida—roughly 250 miles even farther south. Divorces were easy to obtain in Florida back then, so it seems likely that she somehow feigned to move there in order to obtain residency, then sought the legal separation, all while actually living in the Carolinas.

Whatever the details, the divorce was granted on March 18, 1947, and, on April 5, Vicki walked the aisle for the third time in less than six years, marrying Leo at her parents’ house. Suddenly, Vinnie, not yet two years old, had two new siblings and, more consequentially, his first father figure.

“He hit you with his tools, didn’t he?” the Playboy interviewer asked, referring to Leo.

“Sure,” was Vince’s reply.

“He hit your brother, too?” came the follow-up.

“No,” Vince said. “I was the only one of the kids who would speak up, and that’s what provoked the attacks. You would think that after being on the receiving end of numerous attacks I would wise up, but I couldn’t. I refused to. I felt I should say something, even though I knew what the result would be.”

Some of that speaking up, according to Vince, was advocating on behalf of his mother after Leo would hit her. “That’s an awful way to learn how a man behaves,” the interviewer said.

“I learned how not to be,” Vince mused. “One thing I loathe is a man who will strike a woman. There’s never an excuse for that.” That said, the woman in question was not without blame, in Vince’s eyes.

“Was the abuse all physical, or was there sexual abuse, too?” the interviewer asked.

“That’s not anything I would like to embellish,” Vince said. “Just because it was weird.”

“Did it come from the same man?”

“No,” Vince said. “It wasn’t…”—a pause—“… it wasn’t from the male.”

“It’s well known that you’re estranged from your mother,” the reporter pointed out. “Have we found the reason?”

Vince paused. He nodded. All he could bring himself to say was, “Without saying that, I’d say that’s pretty close.”

Not long after the Playboy interview was published, Vince appeared on The Howard Stern Show to talk up a pay-per-view event, WrestleMania X-Seven, and promote his failing proprietary football league, the XFL. But Stern, as is his wont, wanted to talk about sex. The shock jock led off the interview by saying he’d read that Vince was molested by his mother.

“I didn’t say that,” Vince countered in a tone that suggested a rising shield. “That was the inference.”

Stern’s cohost, Robin Quivers, asked, “What did she do?”

Vince didn’t answer.

Stern posited, “I don’t know, but, whatever it was, it was not good.”

Vince blurted out an obviously forced laugh.

“Vince, you get all choked up when you talk about it, right?” Stern asked.

“I’d rather not talk about that stuff,” Vince replied.

Quivers: “Your mother is around and you don’t talk to her?”

Vince: “Uh, not a lot.”

Stern: “Boy, did she blow it. Because man, you’re a billionaire!”

“Does she get any money from the WWF?” Quivers asked, referring to WWE by its then-current name.

Stern interrupted the question to add, “I just realized, when I said, ‘Did she blow it’—that’s the question!” Everyone in the studio yelled out a mock-disapproving “Ohhh!” at the host’s dick joke.

Well, everyone other than Vince.

“Vince, I apologize,” Stern said. “That would be traumatic.”

“That would be traumatic,” Vince said. “Right.”

I once tracked down Terry Lupton, Leo’s grandson through Richard, and spoke to him on the phone. He didn’t remember much about Leo, but what he did wasn’t flattering.

“The only time that I met him was when I was a little, little, little guy,” Terry said. “And I just remember vividly how it was around Leo, and how my dad was around Leo. Even as a grown man with kids and a wife, my dad was still completely scared of Leo.”

The occasion was a fishing trip. “I remember, vividly, my dad talking to us,” Terry recalls, “and saying, ‘Don’t say a word [to Leo]. Nothing.’ Kind of warning us.” Terry did as he was told. “We went fishing with him and, sitting around, eating the fish we caught for the day, I didn’t say a word.”

In the Playboy interview, after Vince had gone on his tangent about not using trauma as a crutch, the reporter offered up a thought: “Surely it must shape a person.”

“No doubt,” came Vince’s reply. “I don’t think we escape our experiences. Things you may think you’ve pushed to the recesses of your mind, they’ll surface at the most inopportune time, when you least expect it. We can use those things, turn them into positives—change for the better. But they do tend to resurface.”

Shortly after they got married, Vicki and Leo were back in North Carolina’s Moore County, building a life for their blended nuclear family, all of whom were now known as Luptons. Indeed, a childhood friend of Rod’s recalls Rod and Vinnie not even knowing how to say their Irish birth surname: according to him, they pronounced it “Mack-Mahone.”

Vince would later say he didn’t know why his parents were separated or what the terms of the separation were. He admitted to occasional fantasies that somehow his mom and his “real dad” would get back together. “Bizarre,” he added. “Obviously, they didn’t.”

Vinnie Lupton first came up in Southern Pines, a poor township with a population of roughly four thousand, snuggled next to the better-known Pinehurst, an affluent golf resort city. Like most southern towns of the time, Southern Pines was segregated: there was a Black side of town and a white side. West Southern Pines had briefly been an independent township entirely comprised of the descendants of enslaved people, from 1923 to 1931, making it one of the first Black-run cities to be incorporated in the state. Southern Pines proper, on the other hand, had long been a “sundown town”—a place where Black people were barred from living or owning businesses.

Vinnie’s first house was right on the dividing line. It “was what we would call a ‘sketchy area’ now,” says Sarah Mathews, a white resident of Vinnie’s generation. She recalls babysitting just a block or two away from the home where Vinnie first lived: “I mean, there were just some trees separating where I was babysitting from the Black community,” she says. “I sat on the floor next to the table with the telephone on it because I was so frightened, so that I could call my parents if I heard any noise. I never babysat there again.”

Vicki volunteered with the town’s Boy Scout troop, played tennis in local tournaments, and even participated in community theater: in August of 1953, she was in On Stage America, which the local paper described as “an old-fashioned musical minstrel [show] with a modern patriotic twist.” She performed as a member of the so-called Pickininny Chorus, presumably in blackface.

In 1956, around when Vinnie was ten, the Lupton unit packed up and moved to distant Weeksville, North Carolina. Located just outside of Elizabeth City, up on the northeast coast, Weeksville was largely farmland, though it seems probable that Leo was hired to do electrical work for a nearby Coast Guard base. There was slightly more contact between the Black and white populations there than in Moore, but it was largely restricted to Black farmers doing underpaid labor for white farmers. The schools were still totally segregated, and Vinnie attended the white one, in a sixth-grade class of just thirty-two kids. It is here that we get our earliest independent glimpse of Vinnie’s personality.

The mythological youth of Vince McMahon is that of a rough-and-tumble hoodlum who barely got out alive. “I was totally unruly,” he told the Playboy interviewer. “Would not go to school. Did things that were unlawful, but I never got caught.” Or, as he put it on another occasion, “It’s frustrating for a child to know that you’re different and you don’t fit in. Maybe you’re not quite as bright and you’re made fun of, and kids will do that. I guess, maybe, I always resorted back to the one common denominator when I was terribly frustrated like that. And that, of course, would be physicality.”

However, the picture that emerges from those who knew him is, surprisingly, of a kind child who made friends with ease. “He was, from what I can remember, fairly popular, and he was liked by the girls as well as the boys,” recalls classmate Shell Davis, who became the boy’s best friend in town. “Most everyone knew him, liked him, that sort of thing.”

Vinnie was not a loud or abrasive child: Rod’s best friend from the period, James Fletcher, says that, despite encountering Vinnie at some length, the younger kid didn’t make a big impression. That said, as Davis puts it, Vinnie “was more extroverted than introverted”; not a show-off, but “very sociable, very friendly, very outgoing to his peers.”

Indeed, despite his claims to the contrary, it appears Vinnie was more of a lover than a fighter until well after he’d entered the world of professional adults. Whatever trauma he endured, it had not made him cruel. Not yet.

After just about a year, Leo moved his family once again, this time to Craven County, where he’d been born. Within just a few months, a belated reunion would, in its way, tilt the axis of history.

For millennia, people around the world have engaged in legitimate wrestling, where people grapple with one another, unaided by weaponry, until one of them is the victor. It has often been called our species’ oldest sport, and it may well be. The Epic of Gilgamesh, the Sumerian epic written more than four thousand years ago, prominently features wrestling. The biblical Jacob (or Ya’akov—“God’s heel”) gained the name “Israel” after a wrestling match. One possible translation of Isra’el is “wrestles with God.”

The Greeks and Romans famously prized the sport. Wrestlers have been heroes in West Africa since time immemorial. Settlers wrestled in America’s colonial days; so did enslaved people. George Washington wrestled, as did Abraham Lincoln, who fought in roughly three hundred matches—indeed, a famous one in New Salem, Illinois, in 1831 made Honest Abe a local celebrity and was a key factor in putting him on the path to politics. Perhaps wrestling, however uncivilized it may seem, is inextricable from civilization.

Irish immigrants of the 1830s and ’40s popularized a native form of Irish wrestling called “collar-and-elbow” in the American Northeast. It was a popular way to defend your Irish region’s honor, in addition to being a hell of a lot of fun to watch. The Civil War and its attendant conscription brought Irish Americans and their customs into contact with countless other men from around the Union. Soon, people from all backgrounds were fascinated by collar-and-elbow. Just two years after the peace at Appomattox, the first American wrestling champion, James Hiram McLaughlin of New York, was crowned.

That’s all well and good, but the real fun was just starting to percolate. English immigrants brought another new style from Europe, called “catch-as-catch-can,” and its holds became the foundation of what we think of as pro wrestling. Yet another style, this one from France but erroneously referred to as “Greco-Roman wrestling,” arrived soon afterward. In all these forms, one would extract a win through a submission or a pin—a “fall,” in the parlance of the trade.

Excitement about wrestling was high and the time was ripe for innovation. However, there is no one person who came up with the idea of staging matches with predetermined outcomes. Rather, it seems to have been an organic convergence of two institutions: athletics and the traveling circus.

Wandering entertainment caravans were another long-standing human creation, and the post–Civil War growth of interest in organized sports opened the door for entrepreneurs and showmen to combine those models and create journeying athletic troupes. In order to guarantee a good time for the spectators, people in charge of the troupes started to covertly stage what were then known as “hippodrome” bouts: matches for which the ending was, unbeknownst to onlookers, mapped out in advance. However, this was never to be divulged to the general populace.

This was when the term kayfabe emerged. Possibly a garbled version of Pig Latin for “fake,” it became a secret code word and one of the core tenets of the trade. Hippodroming was not confined to wrestling—it was, in fact, a general problem in the early days of organized sports in the US—but kayfabe belonged to wrestling alone. While artifice withered away in other sports industries, what became known as “professional” wrestling only got more and more fake.

An oligarchy of promoters started to emerge in the 1910s and early ’20s, when wrestlers like Evan “Strangler” Lewis, Joe “Toots” Mondt, and Robert H. Friedrich (who, confusingly enough, also went by the name “Strangler Lewis”) were national superstars. Soon, characters were the order of the day. Promoters, having abandoned athletic legitimacy behind the scenes, instead made their wrestlers work the crowd into a froth through archetypes. The matches—still billed as legitimate contests—now had clearly differentiated good guys (clean, fit, American) and bad guys (dirty, ugly, often foreign).

It was a genius idea. The nascent motion picture industry capitalized on the soaring popularity of wrestling by regularly putting wrestlers in movies—a tradition that continues to this day, often to great success for all parties involved. Wrestling was a chaotic industry: there was no central governing body, which led to territorial disputes and multiple brawlers claiming to be the national champion. But it was lucrative chaos.

So it’s little wonder that, come 1931, an Irish American named Jess McMahon was interested in getting a piece of the action.

Roderick James “Jess” McMahon— Vince’s grandfather—was born in 1882 to a pair of Irish immigrants. His father, Roderick, died when Jess was only six; his mother, Eliza Dowling McMahon, never remarried and raised the entire family of six children from there on out as a single mom. But Eliza was the heiress to a wealthy real estate developer, and her late husband had also made a small fortune as a landlord. Their lives were softened by their money and by America’s expanding definitions of whiteness.

As a young man, Jess started promoting sports at an athletic club in his home neighborhood of West Harlem and gained a college degree. He married a woman named Rose McGinn. By July 6, 1914, when their second son, Vincent James, was born, Jess was rising to become one of the most successful promoters in New York boxing. He soon put up fights featuring legends such as Jack Johnson and Jess Willard and became matchmaker at the legendary Madison Square Garden in 1925. The venue would become a center of McMahon power.

As of 1929, Jess, Rose, and their kids were living in Rockaway Beach, Queens, and teenage Vincent was studying at the pricey La Salle Military Academy on Long Island. A news item about Jess in the New York Evening Post quoted a letter allegedly written by Vincent to his older brother from a summer camp in Massachusetts, where he wrote that he had “learned how to follow up a left-jab with a right cross knockout punch” and made his brother swear not to tell their father, “for I want to surprise him one of these days.” Fighting was now a family business.

And the business was diversifying: in 1931, Jess, lured by a colleague, made the historically consequential decision to promote his first professional wrestling match. Over the next decade and a half, he would continue working in the world of boxing, but also built out a wrestling fiefdom. He began by setting up pro wrestling matches on Long Island; by decade’s end, he was booking them throughout Kings County, too, becoming one of the leading promoters in the New York City area. In the mid-1940s, he expanded his operations to Washington, DC. In 1946, he sent his son Vincent to live in the nation’s capital and be his man on the ground.

It was good timing for Vincent. He was a year out of the army, unencumbered by the ex-wife and two children he’d left behind in the South. His twenties, before the war, had been spent aimlessly, but now he took to the family business with a fervor. In less than three years, he was hired as the general manager of DC’s Turner’s Arena, the heart of wrestling in the city, where he’d stage matches, as well as basketball games, concerts, and dances. He did well enough that in 1952, he subleased the arena for himself, and secured exclusive rights to promote wrestling in the city. He got married again, to a petite, glamorous local woman named Juanita Wynne.

On November 21, 1954, at age seventy-two, Jess died. He’d had a cerebral hemorrhage at a wrestling match in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, a few days earlier. The business he’d built was firmly in his son’s hands.

Vince Senior was a tall man with pudgy cheeks, a dimpled smile, and voluminous hair. When he was dealing with wrestlers and fellow promoters, he was all smooth edges and easy charm. “He was always in a suit and tie, always dressed impeccably,” recalls one old-school wrestler who worked extensively with Vince Senior. “He was someone who was basically revered by everybody in the industry, just from the way he treated everybody.”

“You could be angry at [Vince Senior] for a payoff; you’d walk in, you’d voice your complaint, you’d walk out, you’d feel great—and yet, you got no more money,” another of his wrestlers would later say. “When he was sticking it to you, he always made you feel good while he was doing it.”

The mid-1950s brought with it the advent of mass television ownership, and wrestling shows—cheap to produce, delightful to watch—became some of the most popular programming of the day. Vince Senior renamed Turner’s Arena as the Capitol Arena and started broadcasting his shows through the DuMont network in 1956. Heavyweight Wrestling from Washington was a smash, airing every Wednesday night in markets across the country.

There were promoters who thought TV would kill live wrestling because people could just watch it remotely without buying a ticket. Vince Senior saw things differently: “We are getting reservation orders from as far north as Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, and as far south as Staunton, Virginia,” he told the Washington Post and Times Herald in March of 1956. “If this is the way television kills promoters, I’m going to die a rich man.”

Within two years, three events changed professional wrestling forever.

One came in August of 1957, when Vince Senior and business partners Toots Mondt and Johnny Doyle founded Capitol Wrestling Corporation—a business entity that would one day be known as WWE.

Another was the release, that same year, of French literary theorist Roland Barthes’s book Mythologies, which included an essay called “The World of Wrestling.” It was a forceful, lyrical meditation on the artifice and glory of the pseudo-sport, and the first great justification of wrestling as art.

“The virtue of all-in wrestling is that it is the spectacle of excess,” Barthes began. “Here we find a grandiloquence which must have been that of ancient theatres.”

He ironically described legitimate, nonstaged combat as “false wrestling”; it was only by faking it that the event could become transcendently real.

“There is no more a problem of truth in wrestling than in the theater,” Barthes declared. “In both, what is expected is the intelligible representation of moral situations which are usually private.” It was now safer for everyone, high or low, to take wrestling seriously.

The third event came with no fanfare and no documentation. Yet, in the long run, it was one of the most pivotal events in wrestling history.

Vinnie Lupton met his real father.

1 FALL (1945–1957)

Vince McMahon, like many of his wrestlers, didn’t grow up with the name he now uses. His father ran a successful wrestling promotion that stretched throughout the Northeast, but Vince was born and raised far away from that empire. He wasn’t even a wrestling fan as a child. WWE has often highlighted the boss’s adoration for the man everyone now calls “Vince Senior.” But until young Vince was an adolescent, he’d never met the man. He was Vinnie Lupton, and he didn’t know if he loved his dad or not.

In his formative years, Vinnie was the son of two people of whom he rarely speaks: Vicki Hanner and Leo Lupton Jr.—his mother and stepfather.

Which is to say, he was a son of North Carolina, however much he may obscure that fact. The sizable Hanner and Lupton clans had been in the state for generations. The Hanners arrived in the colony before it became a founding component of the United States, and by the time of the Civil War, they had settled in as farmers—some of them slaveholders. For example, the most renowned member of Vince’s maternal family prior to him was John Henry Hanner, who, when he died in 1850, held ten people in captivity, making his 614-acre farm (located in what is now Greensboro) one of the area’s larger forced-work camps.

But by the time Victoria Elizabeth Hanner was born in 1920, the family had been in a decades-long decline. Her mother was a farmer’s daughter; her father an itinerant mechanic who rambled back and forth between North and South Carolina, barely making a living while working on automobiles.

Vicki appears to have been born in Florence, South Carolina, and raised in Sanford, North Carolina. She then did a jaunt at Bob Jones College in faraway Cleveland, Tennessee. However, a North Carolina birth index of 1939 informs us that Victoria Hanner—who would have been either eighteen or nineteen at the time—gave birth to a child many miles from both home and school, in Charlotte. In the column for the father’s name, there is only a series of dashes. The baby—Vince’s oldest sibling—was named Gloria Faye Hanner, and there is no record of what became of her.

On December 6, 1941, just a few hours before the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, Vicki married an Ohio-born soldier named Louis Patacca, who was stationed at a nearby military base. That marriage, her first of four, was doomed. Patacca was shipped up to New York City, and Vicki found someone else to occupy her time.

We don’t know how she met Vince’s father, but they may have had their first tryst around June 30, 1942, while New York–based Vincent James McMahon was doing his own military service in Wilmington, North Carolina—a local newspaper item mentions that a visiting “Victoria Patacca” had lost a diamond ring. As of January 1943, Vicki was pregnant with her lover’s child.

Patacca filed a vitriolic divorce petition on August 18, 1943, claiming his estranged wife had withheld the fact of Gloria’s birth from him and had cheated on him with other soldiers. Vicki didn’t respond; the divorce wasn’t resolved as of at least four years later. The military moved Vincent James McMahon back to New York, where his and Vicki’s first child, a boy dubbed Roderick James “Rod” McMahon, was born out of wedlock on October 12.

We do not know what happened between these two young parents for the next eleven months. But we know they got married on September 4, 1944, in South Carolina’s Horry County, where authorities didn’t seem to note that Vicki’s divorce was still pending in the next state over. By the end of November, she was pregnant again.

On August 18, 1945, three days after Japan laid down its arms, Vincent J. McMahon was discharged from the New York base that had been his final station. Vicki was about to give birth in North Carolina.

The couple’s second son entered the world at 7:14 a.m. on August 24, in Pinehurst, North Carolina’s Moore County Hospital. Vicki named the child after its father: Vincent Kennedy McMahon. Kennedy was her mother’s maiden name.

On September 16, young Vince was baptized in a Moore County Catholic church. The Hanners were Presbyterians, but the McMahons were Catholics, so this was probably the last influence the father would have on his son’s life for years.

By the time young Vince was old enough to remember anything, the man was gone.

“You know, I’m not big on excuses,” Vince told an interviewer from Playboy in the latter half of 2000. “When I hear people from the projects, or anywhere else, blame their actions on the way they grew up, I think it’s a crock of shit. You can rise above it.”

The topic of conversation was Vince’s own upbringing. He was talking about being sexually abused as a child.

The reporter pointed out how terrible it must have been for him. Vince bristled. “This country gives you opportunity if you want to take it, so don’t blame your environment,” Vince replied. “I look down on people who use their environment as a crutch.”

The reporter brought up Vince losing his virginity. Vince paused. “That was at a very young age,” he said. “I remember, probably in the first grade, being invited to a matinee film with my stepbrother and his girlfriends, and I remember them playing with me. Playing with my penis, and giggling. I thought that was pretty cool. That was my initiation into sex. At that age you don’t necessarily achieve an erection, but it was cool.”

He also recalled incidents involving a local whom he described as “a girl my age who was, in essence, my cousin”: “I remember the two of us being so curious about each other’s bodies, but not knowing what the hell to do,” Vince said. “We would go into the woods and get naked together. It felt good. And, for some reason, I wanted to put crushed leaves into her.” He told the interviewer he didn’t actually remember when he putatively lost his virginity.

“Your growing-up was pretty accelerated,” the reporter said.

“God, yes,” said Vince.

The interviewer brought up Vince’s childhood family unit. Vince said he lived with his mother “and my real asshole of a stepfather, a man who enjoyed kicking people around.”

“Your stepfather beat you?” the interviewer asked.

Vince’s reply: “Leo Lupton. It’s unfortunate that he died before I could kill him. I would have enjoyed that.”

Leo Hubert Lupton Jr. was born in New Bern, North Carolina, in 1917 and dropped out of high school after his freshman year. He trained as an electrician and married a girl named Peggy Lane in 1939. Their marriage was troubled, to say the least. In May of 1940, Peggy gave birth to their first child, Richard. But scarcely a year later, Leo had been convicted of abandoning his family and was sentenced to “two years on the roads,” according to a brief, cryptic newspaper item. However, a later newspaper item implies he and Peggy were back together three months later, when their daughter, Ernestine—better known as “Teenie”—was born in September of 1941.

Leo’s troubles were compounded upon enlisting in the Navy for service in the Pacific in August of 1944. Although he held the honor of being on a boat that was present in Tokyo Bay when the Japanese instrument of surrender was signed, his wife had a stillbirth while he was at sea. Upon returning to North Carolina, he and Peggy separated, and he held on to the kids. He appears to have moved with them into his parents’ house in the South Carolina town of Mount Pleasant. Vicki’s parents were also living in Mount Pleasant at the time, making it likely that a parental connection was how the couple met.

Vicki filed for divorce from young Vinnie’s father on grounds of desertion, but in a curious way: she filed in faraway Leon County, Florida, the region in the Panhandle that contains Tallahassee, and her listed residence was in Lakeland, Florida—roughly 250 miles even farther south. Divorces were easy to obtain in Florida back then, so it seems likely that she somehow feigned to move there in order to obtain residency, then sought the legal separation, all while actually living in the Carolinas.

Whatever the details, the divorce was granted on March 18, 1947, and, on April 5, Vicki walked the aisle for the third time in less than six years, marrying Leo at her parents’ house. Suddenly, Vinnie, not yet two years old, had two new siblings and, more consequentially, his first father figure.

“He hit you with his tools, didn’t he?” the Playboy interviewer asked, referring to Leo.

“Sure,” was Vince’s reply.

“He hit your brother, too?” came the follow-up.

“No,” Vince said. “I was the only one of the kids who would speak up, and that’s what provoked the attacks. You would think that after being on the receiving end of numerous attacks I would wise up, but I couldn’t. I refused to. I felt I should say something, even though I knew what the result would be.”

Some of that speaking up, according to Vince, was advocating on behalf of his mother after Leo would hit her. “That’s an awful way to learn how a man behaves,” the interviewer said.

“I learned how not to be,” Vince mused. “One thing I loathe is a man who will strike a woman. There’s never an excuse for that.” That said, the woman in question was not without blame, in Vince’s eyes.

“Was the abuse all physical, or was there sexual abuse, too?” the interviewer asked.

“That’s not anything I would like to embellish,” Vince said. “Just because it was weird.”

“Did it come from the same man?”

“No,” Vince said. “It wasn’t…”—a pause—“… it wasn’t from the male.”

“It’s well known that you’re estranged from your mother,” the reporter pointed out. “Have we found the reason?”

Vince paused. He nodded. All he could bring himself to say was, “Without saying that, I’d say that’s pretty close.”

Not long after the Playboy interview was published, Vince appeared on The Howard Stern Show to talk up a pay-per-view event, WrestleMania X-Seven, and promote his failing proprietary football league, the XFL. But Stern, as is his wont, wanted to talk about sex. The shock jock led off the interview by saying he’d read that Vince was molested by his mother.

“I didn’t say that,” Vince countered in a tone that suggested a rising shield. “That was the inference.”

Stern’s cohost, Robin Quivers, asked, “What did she do?”

Vince didn’t answer.

Stern posited, “I don’t know, but, whatever it was, it was not good.”

Vince blurted out an obviously forced laugh.

“Vince, you get all choked up when you talk about it, right?” Stern asked.

“I’d rather not talk about that stuff,” Vince replied.

Quivers: “Your mother is around and you don’t talk to her?”

Vince: “Uh, not a lot.”

Stern: “Boy, did she blow it. Because man, you’re a billionaire!”

“Does she get any money from the WWF?” Quivers asked, referring to WWE by its then-current name.

Stern interrupted the question to add, “I just realized, when I said, ‘Did she blow it’—that’s the question!” Everyone in the studio yelled out a mock-disapproving “Ohhh!” at the host’s dick joke.

Well, everyone other than Vince.

“Vince, I apologize,” Stern said. “That would be traumatic.”

“That would be traumatic,” Vince said. “Right.”

I once tracked down Terry Lupton, Leo’s grandson through Richard, and spoke to him on the phone. He didn’t remember much about Leo, but what he did wasn’t flattering.

“The only time that I met him was when I was a little, little, little guy,” Terry said. “And I just remember vividly how it was around Leo, and how my dad was around Leo. Even as a grown man with kids and a wife, my dad was still completely scared of Leo.”

The occasion was a fishing trip. “I remember, vividly, my dad talking to us,” Terry recalls, “and saying, ‘Don’t say a word [to Leo]. Nothing.’ Kind of warning us.” Terry did as he was told. “We went fishing with him and, sitting around, eating the fish we caught for the day, I didn’t say a word.”

In the Playboy interview, after Vince had gone on his tangent about not using trauma as a crutch, the reporter offered up a thought: “Surely it must shape a person.”

“No doubt,” came Vince’s reply. “I don’t think we escape our experiences. Things you may think you’ve pushed to the recesses of your mind, they’ll surface at the most inopportune time, when you least expect it. We can use those things, turn them into positives—change for the better. But they do tend to resurface.”

Shortly after they got married, Vicki and Leo were back in North Carolina’s Moore County, building a life for their blended nuclear family, all of whom were now known as Luptons. Indeed, a childhood friend of Rod’s recalls Rod and Vinnie not even knowing how to say their Irish birth surname: according to him, they pronounced it “Mack-Mahone.”

Vince would later say he didn’t know why his parents were separated or what the terms of the separation were. He admitted to occasional fantasies that somehow his mom and his “real dad” would get back together. “Bizarre,” he added. “Obviously, they didn’t.”

Vinnie Lupton first came up in Southern Pines, a poor township with a population of roughly four thousand, snuggled next to the better-known Pinehurst, an affluent golf resort city. Like most southern towns of the time, Southern Pines was segregated: there was a Black side of town and a white side. West Southern Pines had briefly been an independent township entirely comprised of the descendants of enslaved people, from 1923 to 1931, making it one of the first Black-run cities to be incorporated in the state. Southern Pines proper, on the other hand, had long been a “sundown town”—a place where Black people were barred from living or owning businesses.

Vinnie’s first house was right on the dividing line. It “was what we would call a ‘sketchy area’ now,” says Sarah Mathews, a white resident of Vinnie’s generation. She recalls babysitting just a block or two away from the home where Vinnie first lived: “I mean, there were just some trees separating where I was babysitting from the Black community,” she says. “I sat on the floor next to the table with the telephone on it because I was so frightened, so that I could call my parents if I heard any noise. I never babysat there again.”

Vicki volunteered with the town’s Boy Scout troop, played tennis in local tournaments, and even participated in community theater: in August of 1953, she was in On Stage America, which the local paper described as “an old-fashioned musical minstrel [show] with a modern patriotic twist.” She performed as a member of the so-called Pickininny Chorus, presumably in blackface.

In 1956, around when Vinnie was ten, the Lupton unit packed up and moved to distant Weeksville, North Carolina. Located just outside of Elizabeth City, up on the northeast coast, Weeksville was largely farmland, though it seems probable that Leo was hired to do electrical work for a nearby Coast Guard base. There was slightly more contact between the Black and white populations there than in Moore, but it was largely restricted to Black farmers doing underpaid labor for white farmers. The schools were still totally segregated, and Vinnie attended the white one, in a sixth-grade class of just thirty-two kids. It is here that we get our earliest independent glimpse of Vinnie’s personality.

The mythological youth of Vince McMahon is that of a rough-and-tumble hoodlum who barely got out alive. “I was totally unruly,” he told the Playboy interviewer. “Would not go to school. Did things that were unlawful, but I never got caught.” Or, as he put it on another occasion, “It’s frustrating for a child to know that you’re different and you don’t fit in. Maybe you’re not quite as bright and you’re made fun of, and kids will do that. I guess, maybe, I always resorted back to the one common denominator when I was terribly frustrated like that. And that, of course, would be physicality.”

However, the picture that emerges from those who knew him is, surprisingly, of a kind child who made friends with ease. “He was, from what I can remember, fairly popular, and he was liked by the girls as well as the boys,” recalls classmate Shell Davis, who became the boy’s best friend in town. “Most everyone knew him, liked him, that sort of thing.”

Vinnie was not a loud or abrasive child: Rod’s best friend from the period, James Fletcher, says that, despite encountering Vinnie at some length, the younger kid didn’t make a big impression. That said, as Davis puts it, Vinnie “was more extroverted than introverted”; not a show-off, but “very sociable, very friendly, very outgoing to his peers.”

Indeed, despite his claims to the contrary, it appears Vinnie was more of a lover than a fighter until well after he’d entered the world of professional adults. Whatever trauma he endured, it had not made him cruel. Not yet.

After just about a year, Leo moved his family once again, this time to Craven County, where he’d been born. Within just a few months, a belated reunion would, in its way, tilt the axis of history.

For millennia, people around the world have engaged in legitimate wrestling, where people grapple with one another, unaided by weaponry, until one of them is the victor. It has often been called our species’ oldest sport, and it may well be. The Epic of Gilgamesh, the Sumerian epic written more than four thousand years ago, prominently features wrestling. The biblical Jacob (or Ya’akov—“God’s heel”) gained the name “Israel” after a wrestling match. One possible translation of Isra’el is “wrestles with God.”

The Greeks and Romans famously prized the sport. Wrestlers have been heroes in West Africa since time immemorial. Settlers wrestled in America’s colonial days; so did enslaved people. George Washington wrestled, as did Abraham Lincoln, who fought in roughly three hundred matches—indeed, a famous one in New Salem, Illinois, in 1831 made Honest Abe a local celebrity and was a key factor in putting him on the path to politics. Perhaps wrestling, however uncivilized it may seem, is inextricable from civilization.

Irish immigrants of the 1830s and ’40s popularized a native form of Irish wrestling called “collar-and-elbow” in the American Northeast. It was a popular way to defend your Irish region’s honor, in addition to being a hell of a lot of fun to watch. The Civil War and its attendant conscription brought Irish Americans and their customs into contact with countless other men from around the Union. Soon, people from all backgrounds were fascinated by collar-and-elbow. Just two years after the peace at Appomattox, the first American wrestling champion, James Hiram McLaughlin of New York, was crowned.

That’s all well and good, but the real fun was just starting to percolate. English immigrants brought another new style from Europe, called “catch-as-catch-can,” and its holds became the foundation of what we think of as pro wrestling. Yet another style, this one from France but erroneously referred to as “Greco-Roman wrestling,” arrived soon afterward. In all these forms, one would extract a win through a submission or a pin—a “fall,” in the parlance of the trade.

Excitement about wrestling was high and the time was ripe for innovation. However, there is no one person who came up with the idea of staging matches with predetermined outcomes. Rather, it seems to have been an organic convergence of two institutions: athletics and the traveling circus.

Wandering entertainment caravans were another long-standing human creation, and the post–Civil War growth of interest in organized sports opened the door for entrepreneurs and showmen to combine those models and create journeying athletic troupes. In order to guarantee a good time for the spectators, people in charge of the troupes started to covertly stage what were then known as “hippodrome” bouts: matches for which the ending was, unbeknownst to onlookers, mapped out in advance. However, this was never to be divulged to the general populace.

This was when the term kayfabe emerged. Possibly a garbled version of Pig Latin for “fake,” it became a secret code word and one of the core tenets of the trade. Hippodroming was not confined to wrestling—it was, in fact, a general problem in the early days of organized sports in the US—but kayfabe belonged to wrestling alone. While artifice withered away in other sports industries, what became known as “professional” wrestling only got more and more fake.

An oligarchy of promoters started to emerge in the 1910s and early ’20s, when wrestlers like Evan “Strangler” Lewis, Joe “Toots” Mondt, and Robert H. Friedrich (who, confusingly enough, also went by the name “Strangler Lewis”) were national superstars. Soon, characters were the order of the day. Promoters, having abandoned athletic legitimacy behind the scenes, instead made their wrestlers work the crowd into a froth through archetypes. The matches—still billed as legitimate contests—now had clearly differentiated good guys (clean, fit, American) and bad guys (dirty, ugly, often foreign).

It was a genius idea. The nascent motion picture industry capitalized on the soaring popularity of wrestling by regularly putting wrestlers in movies—a tradition that continues to this day, often to great success for all parties involved. Wrestling was a chaotic industry: there was no central governing body, which led to territorial disputes and multiple brawlers claiming to be the national champion. But it was lucrative chaos.

So it’s little wonder that, come 1931, an Irish American named Jess McMahon was interested in getting a piece of the action.

Roderick James “Jess” McMahon— Vince’s grandfather—was born in 1882 to a pair of Irish immigrants. His father, Roderick, died when Jess was only six; his mother, Eliza Dowling McMahon, never remarried and raised the entire family of six children from there on out as a single mom. But Eliza was the heiress to a wealthy real estate developer, and her late husband had also made a small fortune as a landlord. Their lives were softened by their money and by America’s expanding definitions of whiteness.

As a young man, Jess started promoting sports at an athletic club in his home neighborhood of West Harlem and gained a college degree. He married a woman named Rose McGinn. By July 6, 1914, when their second son, Vincent James, was born, Jess was rising to become one of the most successful promoters in New York boxing. He soon put up fights featuring legends such as Jack Johnson and Jess Willard and became matchmaker at the legendary Madison Square Garden in 1925. The venue would become a center of McMahon power.

As of 1929, Jess, Rose, and their kids were living in Rockaway Beach, Queens, and teenage Vincent was studying at the pricey La Salle Military Academy on Long Island. A news item about Jess in the New York Evening Post quoted a letter allegedly written by Vincent to his older brother from a summer camp in Massachusetts, where he wrote that he had “learned how to follow up a left-jab with a right cross knockout punch” and made his brother swear not to tell their father, “for I want to surprise him one of these days.” Fighting was now a family business.

And the business was diversifying: in 1931, Jess, lured by a colleague, made the historically consequential decision to promote his first professional wrestling match. Over the next decade and a half, he would continue working in the world of boxing, but also built out a wrestling fiefdom. He began by setting up pro wrestling matches on Long Island; by decade’s end, he was booking them throughout Kings County, too, becoming one of the leading promoters in the New York City area. In the mid-1940s, he expanded his operations to Washington, DC. In 1946, he sent his son Vincent to live in the nation’s capital and be his man on the ground.

It was good timing for Vincent. He was a year out of the army, unencumbered by the ex-wife and two children he’d left behind in the South. His twenties, before the war, had been spent aimlessly, but now he took to the family business with a fervor. In less than three years, he was hired as the general manager of DC’s Turner’s Arena, the heart of wrestling in the city, where he’d stage matches, as well as basketball games, concerts, and dances. He did well enough that in 1952, he subleased the arena for himself, and secured exclusive rights to promote wrestling in the city. He got married again, to a petite, glamorous local woman named Juanita Wynne.

On November 21, 1954, at age seventy-two, Jess died. He’d had a cerebral hemorrhage at a wrestling match in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, a few days earlier. The business he’d built was firmly in his son’s hands.

Vince Senior was a tall man with pudgy cheeks, a dimpled smile, and voluminous hair. When he was dealing with wrestlers and fellow promoters, he was all smooth edges and easy charm. “He was always in a suit and tie, always dressed impeccably,” recalls one old-school wrestler who worked extensively with Vince Senior. “He was someone who was basically revered by everybody in the industry, just from the way he treated everybody.”

“You could be angry at [Vince Senior] for a payoff; you’d walk in, you’d voice your complaint, you’d walk out, you’d feel great—and yet, you got no more money,” another of his wrestlers would later say. “When he was sticking it to you, he always made you feel good while he was doing it.”

The mid-1950s brought with it the advent of mass television ownership, and wrestling shows—cheap to produce, delightful to watch—became some of the most popular programming of the day. Vince Senior renamed Turner’s Arena as the Capitol Arena and started broadcasting his shows through the DuMont network in 1956. Heavyweight Wrestling from Washington was a smash, airing every Wednesday night in markets across the country.

There were promoters who thought TV would kill live wrestling because people could just watch it remotely without buying a ticket. Vince Senior saw things differently: “We are getting reservation orders from as far north as Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, and as far south as Staunton, Virginia,” he told the Washington Post and Times Herald in March of 1956. “If this is the way television kills promoters, I’m going to die a rich man.”

Within two years, three events changed professional wrestling forever.

One came in August of 1957, when Vince Senior and business partners Toots Mondt and Johnny Doyle founded Capitol Wrestling Corporation—a business entity that would one day be known as WWE.

Another was the release, that same year, of French literary theorist Roland Barthes’s book Mythologies, which included an essay called “The World of Wrestling.” It was a forceful, lyrical meditation on the artifice and glory of the pseudo-sport, and the first great justification of wrestling as art.

“The virtue of all-in wrestling is that it is the spectacle of excess,” Barthes began. “Here we find a grandiloquence which must have been that of ancient theatres.”

He ironically described legitimate, nonstaged combat as “false wrestling”; it was only by faking it that the event could become transcendently real.

“There is no more a problem of truth in wrestling than in the theater,” Barthes declared. “In both, what is expected is the intelligible representation of moral situations which are usually private.” It was now safer for everyone, high or low, to take wrestling seriously.

The third event came with no fanfare and no documentation. Yet, in the long run, it was one of the most pivotal events in wrestling history.

Vinnie Lupton met his real father.