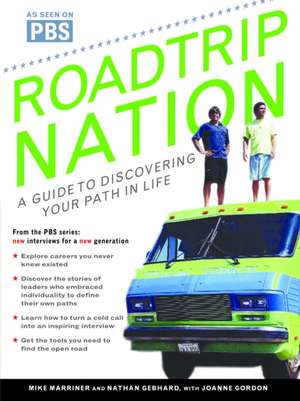

Roadtrip Nation: A Guide to Discovering Your Path in Life

Autor Mike Marriner, Nathan Geghard, Joanne Gordonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2006

“You should be a lawyer, a doctor, an accountant, a consultant, blah, blah, blah. Everywhere you turn people try to tell you who to be and what to do with your life. We call that the noise. Block it. Shed it. Leave it for the conformists. As a generation, we need to get back to focusing on individuality. Self-construction rather than mass production. Define your own road in life instead of traveling down someone else’s. Listen to yourself. Your road is the open road. Find it.”

—Mike and Nathan

*****

After college Mike Marriner and Nathan Gebhard had no idea what to do with their lives. All they’d been exposed to were standard career paths like doctor and consultant—roads that didn’t fit them at all.

To see what else was out there they took a roadtrip across the nation in a huge forty-foot RV to meet with people who had successfully defined their own paths in life—including the chairman of Starbucks; a lobsterman from Maine; the director of Saturday Night Live; the conductor of the Boston Philharmonic; the first female Supreme Court Justice of the United States; head stylist for Madonna; and the CEO of National Geographic Ventures. All told, one hundred and forty people candidly shared their stories about how they got from college to the present. Now in Roadtrip Nation, Mike and Nathan share the most compelling tales with you.

Along the way, they explain how you, too, can get out there and meet people on your own. From making cold calls to asking stimulating interview questions, Roadtrip Nation will give you the tools to create a life that you’ll look back on and say: “I was true to myself every step of the way.”

Preț: 121.19 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 182

Preț estimativ în valută:

23.19€ • 24.28$ • 19.19£

23.19€ • 24.28$ • 19.19£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345496386

ISBN-10: 0345496388

Pagini: 281

Ilustrații: PHOTOS THROUGHOUT

Dimensiuni: 159 x 207 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.44 kg

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0345496388

Pagini: 281

Ilustrații: PHOTOS THROUGHOUT

Dimensiuni: 159 x 207 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.44 kg

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

Extras

SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA

EPIPHANY ROAD

Gary Erickson

Berkeley, California

Founder, Owner, and CEO

Clif Bar

California Polytechnic State University,

San Luis Obispo

GARY ERICKSON'S OPEN ROAD MAP

"Cruises through college" at California Polytech and gets a business degree.

Works as a mountain guide; travels the world for a year.

Returns home to help launch a bike seat factory;

manages it for ten years.

Begins bike racing professionally; sells Greek pastries on the side.

Takes his "epiphany ride": a 175-mile one-day bike ride during which, after five not-so-delicious Power Bars,

he decides to make a tasty alternative.

Founds Clif Bar within the year.

I can't eat another Power Bar.

I can make something better than this.

Gary Erickson didn't just graduate from college and say "Gee, I think I'll start a health bar company." Like many of the people we talked to on our roadtrip, Gary's current place in life is not the result of some grand plan he put in place after college. Instead, it's an unexpected culmination of experiences and hobbies that each reflected his interests at a particular time in his life. One decision eventually opened doors to other opportunities, and then more choices. Gary was the first interview we did on the roadtrip, and he told us his story from the passenger seat of the RV. He had a shaved head and wore running shoes, black pants, and a black golf shirt with a white striped collar. "The only thing black and white about my life is my shirt," he said. That's an apt summary of his road because Gary is definitely comfortable living in the gray zone.

I cruised through college not knowing what I was going to do. I was a business major because I always had entrepreneurial ideas, and I thought I'd open up a ski shop or something. But halfway through school I changed my mind and didn't think business was something I'd do after graduation. For a while my life was about music. I played the trumpet, I was into jazz and thought about being in a band. It looked great, but then I realized that I didn't want to be on the road playing every night, traveling all over the place.

When I graduated from college I worked as a mountain guide and spent a few years taking kids hiking and sleeping outdoors, climbing big walls in the valley or wherever I could go. For a while climbing was my thing.

Then I traveled around the world for a year and my parents were pretty cool about it. They gave me a few hundred bucks and said, "Have a great time," which surprised me because they're pretty conservative. I got a backpack and took off to Europe, the Middle East, and India. It was a $10-a-day thing back then, one of those change-your-life-forever kind of trips.

Seeing how the rest of the world lived changed my worldview. When I got home I was kind of down. I wondered, "Now what do I do?" The trip taught me that nobody has "the answer." There's no roadmap. I had grown up in suburbia with Evangelical parents, and things seemed pretty black and white. But when I came back to the United States, I realized that there is no black and white. There is a huge gray area, and I was fine with living in the gray.

I went to work for my brother at a foundry he owned that made high-tech metal parts and cool aluminum castings. He had just sold part of his company to another company that made bicycle accessories, and they asked him to open a bike seat factory from the ground up. He asked me if I wanted to come along to sweep the floors or do whatever.

I did that for about eight months, until my brother went back to the foundry and I became the plant manager. I designed bike seats for ten years. Eventually we moved the production to Italy, which was really cool because I got to travel to Italy five times a year. I'd just go there and hang out and ride my bike. I started riding the Alps.

Then it all started to come together.

I had become a sort of consultant for my brother's bike seat factory, making $7,000 to $10,000 a year, living in a garage in Berkeley with my dog, and going to Italy five times a year. I had also started bike racing and two things happened.

First, I got an idea when I was at my mom's house in 1986. She was always inventing recipes, and one day she made a Greek pastry with a meat and vegetable filling. I sat at her kitchen table and said, "Wow! I bet these things would sell." After all, I still had the entrepreneurial bug. I didn't care about the money. I just wanted to do my own thing.

I asked a friend to help me with the business. My mom made a bunch of samples that we put in pink boxes and took around to some delis in the San Francisco Bay area. People actually placed orders and boom [snaps fingers] we were in business, just like that!

I juggled the baking business with bike racing.

A few years later something happened that I now call "the epiphany ride." I was on a long, 175-mile, one-day bike ride with my friend Jay, and we had six Power Bars with us. After eating five I said, "That's it! I can't eat another one. These things suck!" [Laughs.] We went to a 7-Eleven and bought some powdered doughnuts.

There I was: I owned a bakery, I was racing bikes, and I was in the bike industry. Plus, all the racers were eating Power Bars, which were selling well but lacked taste. I turned to my friend Jay and said, "Man, I can make something better than this."

I had my bakery try to make a product that combined nutrition and taste, and about fourteen months later we introduced Clif Bar.

Was I fearful along the way? I had learned from rock climbing not to be fearful because fear paralyzes you. Years and years of climbing taught me to stay calm, which was key because you can't have fear when running a company, either. Fear spreads.

Last year the company marked the ten-year anniversary of the epiphany ride, and we took employees on the 175-mile trek to celebrate the birth of the idea.

There you have it. It's all been one big adventure.

SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA

MAY THE FORCE

BE WITH YOU

Dennis Muren

San Rafael, California

Senior Visual Effects Supervisor

Industrial Light & Magic

California State University,

Los Angeles

Pasadena City College

DENNIS MUREN'S OPEN ROAD MAP

Enchanted by visual effects as a kid, spends allowance on film.

Takes "practical route" in college with advertising major; graduates and takes freelance commercial gigs.

Pressure to get practical and make money leads to job hunting; spies "inhalation therapy" in classifieds ads.

In a last-ditch effort to make it in film, drops his price to work on his first "union film," with George Lucas.

Star Wars catapults his career; still working and trying to

surprise audiences as well as himself.

Go into something

that no one else is going into.

Sitting before us in a black-and-white Hawaiian shirt was Dennis Muren, the man behind visual effects for movies like E.T., The Extra-Terrestrial, Terminator 2: Judgment Day and the Star Wars flicks. He has won eight Academy Awards for Best Achievement in Visual Effects throughout his career, which is ironic when you consider that when he started out in the 1960s, visual effects wasn't even a career! Dennis had no road to follow and very few mentors, yet he clung to his fascination with visual effects. We had lunch with him just outside the set of the latest Star Wars film, Episode II: Attack of the Clones. They wouldn't let us on the set, but we snuck a few peeks anyway.

I grew up thirty minutes from Hollywood, but it might as well have been further because I didn't know anyone in the business.

When I was six or seven, I liked visual effects--I don't even know why. There were no video cameras in those days, and I used an eight-millimeter camera in high school and college. I used my allowance to buy film, but back then you shot only two minutes of film, sent it to Kodak to be developed, and couldn't get it back for two weeks! That made everything I shot really important. It made me focus on every little thing. But it was just a hobby. I never thought it would be a career.

When I went to college, my folks told me to major in business so I had something to fall back on. I minored in advertising so at least I could do special effects for commercials. I crammed my classes into Tuesdays and Thursdays so I could make movies Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays.

Between classes some friends and I spent two years making a low-budget film for $3,500. I sold it to a distributor for $6,000 or $7,000. He put another $40,000 into it, redid the sound, added some more shots, released it in L.A., and showed it all over the country. I think I learned more doing that film than I would have during four years at film school. So I am really self-taught. I just followed what I liked to do.

My friends and I also went to films that we thought were really neat. Afterward, we'd call up all the people who did the movies' special effects and ask them about their work. These people had never gotten a call from anybody asking them about their work before, so they were thrilled to talk about it.

I sort of goofed off in my early twenties and had, like, four different jobs a year and earned maybe $1,000 for a commercial. I'm an independent person and didn't like the idea of working nine-to-five every day. Besides, if I had been pushed into a job that took fifty hours a week, I wouldn't have been able to learn what I did. People need time to find what they're good at.

Still, I lived at home and knew that I couldn't go on much longer, so one day I went through the Los Angeles Times classified section and found a job for inhalation therapy, something about teaching people to breathe. I'd probably work in a hospital, and I could do it while I continued my hobbies.

Then, Star Wars came along.

Most of the movies being made with special effects back then were union movies, and I didn't care to work on them because they were too structured. But at some point I thought I should at least work on one and see what it was like. I picked Star Wars because I figured that if I was going to do a Hollywood movie, I might as well do it with a director I liked, and I really liked George Lucas. I didn't know him, but I knew John Dykstra, so I contacted him. I pushed for an interview, got it, and told them how much money I wanted. They said they couldn't afford to pay me.

So, literally, I was faced with this choice: Did I want to do Star Wars for less money than I made doing commercials or did I want to do inhalation therapy and wait for another commercial to come along?

I called John Dykstra and dropped my price. I figured it would be a steppingstone.

From the very beginning I tried to separate myself from everyone else. I didn't just deliver a shot, I took it further. I would try to shoot something in a way that people would look and say, "I never knew that was possible." I'm passionate about the end result. I like looking at my work when it's done and saying "Wow!" All the rest of the process is just a way to get to that end result. That's what drives me. The process can be hard--fun at first, but tough to do--and it's really neat when it's all over.

Over the years, technology has made the work easier, and in some ways harder. Now you can buy software and two dozen books about doing visual effects. There are a lot of people coming into the profession that know how to use the tools, but what they need to learn is how to apply the effects within the movie. They have to know how movies are made, about direction, photography, lighting, composition, and how to tell a story. And they must have interpersonal skills, because on every movie you work with dozens of people.

I'm going through an interesting period now because I've done so much stuff for so long that I have to work hard to make it interesting. So I try to find a hook in every project, something I've never done before. I imagine that my work is obsolete as soon as it's done, so I look for the next thing and always try to come up with something new so I don't repeat myself. The audience can get bored and you have to keep surprising people.

I did luck out. Steven Spielberg and George came along, all the Baby Boomers grew up and wanted to see these movies, and society became very visually oriented. I don't know if I would do the same thing today. I got into this because special effects were just that: special. They were unique and different. They're not special any more. You see them everywhere.

Yet because they were so rare, I went through a difficult period before Star Wars. I felt like my passion had no future because there were no jobs. But someone at that time told me, or maybe I overheard it said, that what people should do when they're young is to go into something that nobody else is going into. And if it ever becomes fashionable, then there you are. And that, in fact, is my story.

The path is

never linear

going forward.

It's only linear

in the

rearview mirror.

Sipping coffee from the passenger seat in the RV, Randy was kind enough to point out the crack in our windshield. From that point forward he didn't hold back. Randy had--in his own words--screwed up after college by taking the safe, predictable road: He became a lawyer. His road out of law did not happen overnight.

As a "virtual CEO" in Silicon Valley, Randy hops from young company to young company, helping to fund and run them. He's got a dozen projects at any one time, and past projects include helping TiVo and WebTV. Before he went independent, Randy was a lawyer for Apple, CEO and president of Lucas Arts Entertainment, and a founder of Claris Corporation.

Engage in what truly motivates you now. Don't defer it by wearing a suit and going to work on Wall Street in the hope that you'll put away enough money to figure out what you really want to do. You will never get there that way. I can spout off about this because I made this mistake when I graduated from Brown.

EPIPHANY ROAD

Gary Erickson

Berkeley, California

Founder, Owner, and CEO

Clif Bar

California Polytechnic State University,

San Luis Obispo

GARY ERICKSON'S OPEN ROAD MAP

"Cruises through college" at California Polytech and gets a business degree.

Works as a mountain guide; travels the world for a year.

Returns home to help launch a bike seat factory;

manages it for ten years.

Begins bike racing professionally; sells Greek pastries on the side.

Takes his "epiphany ride": a 175-mile one-day bike ride during which, after five not-so-delicious Power Bars,

he decides to make a tasty alternative.

Founds Clif Bar within the year.

I can't eat another Power Bar.

I can make something better than this.

Gary Erickson didn't just graduate from college and say "Gee, I think I'll start a health bar company." Like many of the people we talked to on our roadtrip, Gary's current place in life is not the result of some grand plan he put in place after college. Instead, it's an unexpected culmination of experiences and hobbies that each reflected his interests at a particular time in his life. One decision eventually opened doors to other opportunities, and then more choices. Gary was the first interview we did on the roadtrip, and he told us his story from the passenger seat of the RV. He had a shaved head and wore running shoes, black pants, and a black golf shirt with a white striped collar. "The only thing black and white about my life is my shirt," he said. That's an apt summary of his road because Gary is definitely comfortable living in the gray zone.

I cruised through college not knowing what I was going to do. I was a business major because I always had entrepreneurial ideas, and I thought I'd open up a ski shop or something. But halfway through school I changed my mind and didn't think business was something I'd do after graduation. For a while my life was about music. I played the trumpet, I was into jazz and thought about being in a band. It looked great, but then I realized that I didn't want to be on the road playing every night, traveling all over the place.

When I graduated from college I worked as a mountain guide and spent a few years taking kids hiking and sleeping outdoors, climbing big walls in the valley or wherever I could go. For a while climbing was my thing.

Then I traveled around the world for a year and my parents were pretty cool about it. They gave me a few hundred bucks and said, "Have a great time," which surprised me because they're pretty conservative. I got a backpack and took off to Europe, the Middle East, and India. It was a $10-a-day thing back then, one of those change-your-life-forever kind of trips.

Seeing how the rest of the world lived changed my worldview. When I got home I was kind of down. I wondered, "Now what do I do?" The trip taught me that nobody has "the answer." There's no roadmap. I had grown up in suburbia with Evangelical parents, and things seemed pretty black and white. But when I came back to the United States, I realized that there is no black and white. There is a huge gray area, and I was fine with living in the gray.

I went to work for my brother at a foundry he owned that made high-tech metal parts and cool aluminum castings. He had just sold part of his company to another company that made bicycle accessories, and they asked him to open a bike seat factory from the ground up. He asked me if I wanted to come along to sweep the floors or do whatever.

I did that for about eight months, until my brother went back to the foundry and I became the plant manager. I designed bike seats for ten years. Eventually we moved the production to Italy, which was really cool because I got to travel to Italy five times a year. I'd just go there and hang out and ride my bike. I started riding the Alps.

Then it all started to come together.

I had become a sort of consultant for my brother's bike seat factory, making $7,000 to $10,000 a year, living in a garage in Berkeley with my dog, and going to Italy five times a year. I had also started bike racing and two things happened.

First, I got an idea when I was at my mom's house in 1986. She was always inventing recipes, and one day she made a Greek pastry with a meat and vegetable filling. I sat at her kitchen table and said, "Wow! I bet these things would sell." After all, I still had the entrepreneurial bug. I didn't care about the money. I just wanted to do my own thing.

I asked a friend to help me with the business. My mom made a bunch of samples that we put in pink boxes and took around to some delis in the San Francisco Bay area. People actually placed orders and boom [snaps fingers] we were in business, just like that!

I juggled the baking business with bike racing.

A few years later something happened that I now call "the epiphany ride." I was on a long, 175-mile, one-day bike ride with my friend Jay, and we had six Power Bars with us. After eating five I said, "That's it! I can't eat another one. These things suck!" [Laughs.] We went to a 7-Eleven and bought some powdered doughnuts.

There I was: I owned a bakery, I was racing bikes, and I was in the bike industry. Plus, all the racers were eating Power Bars, which were selling well but lacked taste. I turned to my friend Jay and said, "Man, I can make something better than this."

I had my bakery try to make a product that combined nutrition and taste, and about fourteen months later we introduced Clif Bar.

Was I fearful along the way? I had learned from rock climbing not to be fearful because fear paralyzes you. Years and years of climbing taught me to stay calm, which was key because you can't have fear when running a company, either. Fear spreads.

Last year the company marked the ten-year anniversary of the epiphany ride, and we took employees on the 175-mile trek to celebrate the birth of the idea.

There you have it. It's all been one big adventure.

SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA

MAY THE FORCE

BE WITH YOU

Dennis Muren

San Rafael, California

Senior Visual Effects Supervisor

Industrial Light & Magic

California State University,

Los Angeles

Pasadena City College

DENNIS MUREN'S OPEN ROAD MAP

Enchanted by visual effects as a kid, spends allowance on film.

Takes "practical route" in college with advertising major; graduates and takes freelance commercial gigs.

Pressure to get practical and make money leads to job hunting; spies "inhalation therapy" in classifieds ads.

In a last-ditch effort to make it in film, drops his price to work on his first "union film," with George Lucas.

Star Wars catapults his career; still working and trying to

surprise audiences as well as himself.

Go into something

that no one else is going into.

Sitting before us in a black-and-white Hawaiian shirt was Dennis Muren, the man behind visual effects for movies like E.T., The Extra-Terrestrial, Terminator 2: Judgment Day and the Star Wars flicks. He has won eight Academy Awards for Best Achievement in Visual Effects throughout his career, which is ironic when you consider that when he started out in the 1960s, visual effects wasn't even a career! Dennis had no road to follow and very few mentors, yet he clung to his fascination with visual effects. We had lunch with him just outside the set of the latest Star Wars film, Episode II: Attack of the Clones. They wouldn't let us on the set, but we snuck a few peeks anyway.

I grew up thirty minutes from Hollywood, but it might as well have been further because I didn't know anyone in the business.

When I was six or seven, I liked visual effects--I don't even know why. There were no video cameras in those days, and I used an eight-millimeter camera in high school and college. I used my allowance to buy film, but back then you shot only two minutes of film, sent it to Kodak to be developed, and couldn't get it back for two weeks! That made everything I shot really important. It made me focus on every little thing. But it was just a hobby. I never thought it would be a career.

When I went to college, my folks told me to major in business so I had something to fall back on. I minored in advertising so at least I could do special effects for commercials. I crammed my classes into Tuesdays and Thursdays so I could make movies Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays.

Between classes some friends and I spent two years making a low-budget film for $3,500. I sold it to a distributor for $6,000 or $7,000. He put another $40,000 into it, redid the sound, added some more shots, released it in L.A., and showed it all over the country. I think I learned more doing that film than I would have during four years at film school. So I am really self-taught. I just followed what I liked to do.

My friends and I also went to films that we thought were really neat. Afterward, we'd call up all the people who did the movies' special effects and ask them about their work. These people had never gotten a call from anybody asking them about their work before, so they were thrilled to talk about it.

I sort of goofed off in my early twenties and had, like, four different jobs a year and earned maybe $1,000 for a commercial. I'm an independent person and didn't like the idea of working nine-to-five every day. Besides, if I had been pushed into a job that took fifty hours a week, I wouldn't have been able to learn what I did. People need time to find what they're good at.

Still, I lived at home and knew that I couldn't go on much longer, so one day I went through the Los Angeles Times classified section and found a job for inhalation therapy, something about teaching people to breathe. I'd probably work in a hospital, and I could do it while I continued my hobbies.

Then, Star Wars came along.

Most of the movies being made with special effects back then were union movies, and I didn't care to work on them because they were too structured. But at some point I thought I should at least work on one and see what it was like. I picked Star Wars because I figured that if I was going to do a Hollywood movie, I might as well do it with a director I liked, and I really liked George Lucas. I didn't know him, but I knew John Dykstra, so I contacted him. I pushed for an interview, got it, and told them how much money I wanted. They said they couldn't afford to pay me.

So, literally, I was faced with this choice: Did I want to do Star Wars for less money than I made doing commercials or did I want to do inhalation therapy and wait for another commercial to come along?

I called John Dykstra and dropped my price. I figured it would be a steppingstone.

From the very beginning I tried to separate myself from everyone else. I didn't just deliver a shot, I took it further. I would try to shoot something in a way that people would look and say, "I never knew that was possible." I'm passionate about the end result. I like looking at my work when it's done and saying "Wow!" All the rest of the process is just a way to get to that end result. That's what drives me. The process can be hard--fun at first, but tough to do--and it's really neat when it's all over.

Over the years, technology has made the work easier, and in some ways harder. Now you can buy software and two dozen books about doing visual effects. There are a lot of people coming into the profession that know how to use the tools, but what they need to learn is how to apply the effects within the movie. They have to know how movies are made, about direction, photography, lighting, composition, and how to tell a story. And they must have interpersonal skills, because on every movie you work with dozens of people.

I'm going through an interesting period now because I've done so much stuff for so long that I have to work hard to make it interesting. So I try to find a hook in every project, something I've never done before. I imagine that my work is obsolete as soon as it's done, so I look for the next thing and always try to come up with something new so I don't repeat myself. The audience can get bored and you have to keep surprising people.

I did luck out. Steven Spielberg and George came along, all the Baby Boomers grew up and wanted to see these movies, and society became very visually oriented. I don't know if I would do the same thing today. I got into this because special effects were just that: special. They were unique and different. They're not special any more. You see them everywhere.

Yet because they were so rare, I went through a difficult period before Star Wars. I felt like my passion had no future because there were no jobs. But someone at that time told me, or maybe I overheard it said, that what people should do when they're young is to go into something that nobody else is going into. And if it ever becomes fashionable, then there you are. And that, in fact, is my story.

The path is

never linear

going forward.

It's only linear

in the

rearview mirror.

Sipping coffee from the passenger seat in the RV, Randy was kind enough to point out the crack in our windshield. From that point forward he didn't hold back. Randy had--in his own words--screwed up after college by taking the safe, predictable road: He became a lawyer. His road out of law did not happen overnight.

As a "virtual CEO" in Silicon Valley, Randy hops from young company to young company, helping to fund and run them. He's got a dozen projects at any one time, and past projects include helping TiVo and WebTV. Before he went independent, Randy was a lawyer for Apple, CEO and president of Lucas Arts Entertainment, and a founder of Claris Corporation.

Engage in what truly motivates you now. Don't defer it by wearing a suit and going to work on Wall Street in the hope that you'll put away enough money to figure out what you really want to do. You will never get there that way. I can spout off about this because I made this mistake when I graduated from Brown.