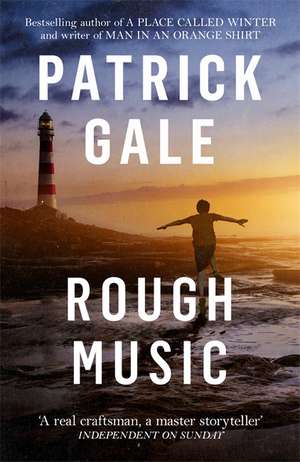

Rough Music

Autor Patrick Galeen Limba Engleză Paperback – 18 aug 2018

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 54.88 lei 3-5 săpt. | +29.40 lei 4-10 zile |

| Headline – 18 aug 2018 | 54.88 lei 3-5 săpt. | +29.40 lei 4-10 zile |

| BALLANTINE BOOKS – 31 mai 2002 | 120.87 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 54.88 lei

Preț vechi: 70.82 lei

-23% Nou

Puncte Express: 82

Preț estimativ în valută:

10.50€ • 10.96$ • 8.67£

10.50€ • 10.96$ • 8.67£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 25 martie-08 aprilie

Livrare express 08-14 martie pentru 39.39 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781472255402

ISBN-10: 1472255402

Pagini: 464

Dimensiuni: 128 x 196 x 32 mm

Greutate: 0.33 kg

Editura: Headline

ISBN-10: 1472255402

Pagini: 464

Dimensiuni: 128 x 196 x 32 mm

Greutate: 0.33 kg

Editura: Headline

Notă biografică

Patrick Gale was born on the Isle of Wight. He spent his infancy at Wandsworth Prison, which his father governed, then grew up in Winchester before going to Oxford University. He now lives on a farm near Land's End. One of this country's best-loved novelists, his most recent works are A Perfectly Good Man, the Richard and Judy bestseller Notes From An Exhibition, the Costa-shortlisted A Place Called Winter and Take Nothing With You. His original BBC television drama, Man In An Orange Shirt, was shown to great acclaim in 2017 as part of the BBC's Queer Britannia series, leading viewers around the world to discover his novels.

Extras

She walked across the sand carrying a shoe in either hand, drawn forward as much by the great blue moon up ahead as by the sound of the breaking waves. The moon had a ring around it which promised or threatened something, she forgot what exactly.

The chill of the foam shocked her skin. She stood still and felt the delicious tug beneath her soles as the water sucked sand out from under them. The water was as cold as death.

If I stood here long enough, she thought, just stood, the sea would draw out more and more sand from under me and bring more and more back in. Little by little I’d sink, ankles already, knees soon, then waist, then belly.

She imagined standing up to her tingling breasts in sucking, salty sand. When the first, disarmingly little wave struck her in the face, would she panic? Would she, instead, laugh, as they said, inappropriately?

She dared herself not to move.

The moon was nearly full. She could see the headland on the far side of the estuary mouth and its stumpy, striped lighthouse. She could see the foam flung and drawn, flung and drawn about her. He was striding across the little beach behind her; she could tell without turning. Would his hands touch her first or would she merely feel the jacket he draped about her? Would he call out from yards away or would she hear his voice soft and sudden when his lips were only inches from her neck?

Her resolution not to turn stiffened her spine. Watching weeds and foam rush away from her for long enough made it feel as though the sea and beach were motionless and it was only she who was gliding back and forth on mysterious salty tracks.

I love you. She felt the words well up. I love you more than words can say. Which was true, of course, because when she felt his steadying hands about her shoulders at last and the brush of his lips on her neck, all that came from her mouth was, “I turn you. Turn my words away?”

BLUE HOUSE

“Actually I feel a bit of a fraud being here,” Will told her. “I’m basically a happy man. No. There’s no basically about it. I’m happy. I am a happy man.”

“Good,” she said, crossing her legs and caressing an ankle as if to smooth out a crease she found there. “What makes you say that?”

“That I’m happy?”

She nodded.

“Well.” He uncrossed his legs, sat back in the sofa and peered out of her study window. He saw the waters of the Bross glittering at the edge of Boniface Gardens, two walkers pausing, briefly allied by the gamboling of their dogs. “I imagine you usually see people at their wit’s end. People with depression or insoluble problems.”

“Occasionally. Some people come to me merely because they’ve lost their way.”

He detected a certain sacerdotal smugness in her tone and suspected he hated her. “Well I’m here because a friend bought me a handful of sessions for my birthday. She thinks I need them.”

“Do you mind?”

He shrugged, laughed. “Makes a change from socks and book tokens.”

“But you don’t feel you need to be here.”

“I . . . I know it sounds arrogant but no, I don’t. Not especially. It’s just that it would have been rude not to come, even though she’ll be far too discreet to ask how I get on with you. If I didn’t come, I’d be rejecting her present and I’d hate to do that. I love her.”

“Her being?”

“Harriet. My best friend. She’s like a second sister but I think of her as a friend first and family second.”

“You have more loyalty to friends than family?”

“I didn’t say that. But you know how it is; people move on from family and choose new allies. It’s part of becoming an adult. I feel I’m moving on too. A little late in the day, I suppose.”

“Your best friend’s a woman.”

“Is that unusual?” She said nothing, waiting for him to speak. “I suppose it is,” he went on. “I’m just not a bloke’s bloke. I never have been. I find women more congenial, more evolved. I mean I’m perfectly happy being a man, but I find I have more in common with women.”

“Such as?”

He did hate her. He hated her royally. “The things we laugh at. The things we do with our free time. And, okay, I suppose you’ll want to talk about this—”

“I don’t want to talk about anything you don’t want to talk about.”

“Whatever. We also share sexual interests. I mean we like the same thing.”

“You’re homosexual?”

“I’m gay.” He smiled, determined to charm her, but she was impervious and vouchsafed no more than a wintry smile. “I told you. I’m a happy man.”

“Your sexuality isn’t a problem for you.”

“It never has been. It’s a constant source of delight. Not a day goes by when I don’t thank God. If anything I’m relieved. Especially now my friends are all having children.”

“You never wanted children.”

“Of course. Sometimes. Hats jokes that if she dies I can have hers. But no. The impulse came and went. There are more than enough children in the world and I’m not so obsessed with seeing myself reproduced. Besides, one of my nephews is the spitting image of me, which has taken care of that. I love my own company. I don’t think I’m selfish exactly but I’m self-sufficient.”

“What about settling down? You’re, what, thirty-five?”

“Thank you for that. I turned forty earlier this year. I have settled down. I have a satisfying job, a nice flat. I just happen to have settled down alone.”

“And watching all those girlfriends settled with their partners doesn’t make you want a significant other.”

“Oh. I have one of those. Sort of, I suppose. He’s really why I’m here. I made a promise to him. It was a joke really, but I told Harriet and—”

“Tell me about him.”

He paused. Glanced out at the view again. “Sorry,” he said. “It’s private.”

“Whatever you tell me—”

“—is in strictest confidence. Yes. I know. But we’ve barely met, you’re still a stranger to me and I’d rather not talk about him just now. It’s not a painful situation. He’s a lovely man. He makes me happy. But I didn’t come here to talk about him.”

A slight, attentive raising of her eyebrows asked, So what did you come to talk about?

“Shouldn’t we start with my childhood?” he said. “Isn’t that the usual thing?”

“If you like.”

“I warn you. I wasn’t abused. I wasn’t neglected. I love my parents and I loved my childhood. It was very, very happy.”

“Tell me about it.”

The chill of the foam shocked her skin. She stood still and felt the delicious tug beneath her soles as the water sucked sand out from under them. The water was as cold as death.

If I stood here long enough, she thought, just stood, the sea would draw out more and more sand from under me and bring more and more back in. Little by little I’d sink, ankles already, knees soon, then waist, then belly.

She imagined standing up to her tingling breasts in sucking, salty sand. When the first, disarmingly little wave struck her in the face, would she panic? Would she, instead, laugh, as they said, inappropriately?

She dared herself not to move.

The moon was nearly full. She could see the headland on the far side of the estuary mouth and its stumpy, striped lighthouse. She could see the foam flung and drawn, flung and drawn about her. He was striding across the little beach behind her; she could tell without turning. Would his hands touch her first or would she merely feel the jacket he draped about her? Would he call out from yards away or would she hear his voice soft and sudden when his lips were only inches from her neck?

Her resolution not to turn stiffened her spine. Watching weeds and foam rush away from her for long enough made it feel as though the sea and beach were motionless and it was only she who was gliding back and forth on mysterious salty tracks.

I love you. She felt the words well up. I love you more than words can say. Which was true, of course, because when she felt his steadying hands about her shoulders at last and the brush of his lips on her neck, all that came from her mouth was, “I turn you. Turn my words away?”

BLUE HOUSE

“Actually I feel a bit of a fraud being here,” Will told her. “I’m basically a happy man. No. There’s no basically about it. I’m happy. I am a happy man.”

“Good,” she said, crossing her legs and caressing an ankle as if to smooth out a crease she found there. “What makes you say that?”

“That I’m happy?”

She nodded.

“Well.” He uncrossed his legs, sat back in the sofa and peered out of her study window. He saw the waters of the Bross glittering at the edge of Boniface Gardens, two walkers pausing, briefly allied by the gamboling of their dogs. “I imagine you usually see people at their wit’s end. People with depression or insoluble problems.”

“Occasionally. Some people come to me merely because they’ve lost their way.”

He detected a certain sacerdotal smugness in her tone and suspected he hated her. “Well I’m here because a friend bought me a handful of sessions for my birthday. She thinks I need them.”

“Do you mind?”

He shrugged, laughed. “Makes a change from socks and book tokens.”

“But you don’t feel you need to be here.”

“I . . . I know it sounds arrogant but no, I don’t. Not especially. It’s just that it would have been rude not to come, even though she’ll be far too discreet to ask how I get on with you. If I didn’t come, I’d be rejecting her present and I’d hate to do that. I love her.”

“Her being?”

“Harriet. My best friend. She’s like a second sister but I think of her as a friend first and family second.”

“You have more loyalty to friends than family?”

“I didn’t say that. But you know how it is; people move on from family and choose new allies. It’s part of becoming an adult. I feel I’m moving on too. A little late in the day, I suppose.”

“Your best friend’s a woman.”

“Is that unusual?” She said nothing, waiting for him to speak. “I suppose it is,” he went on. “I’m just not a bloke’s bloke. I never have been. I find women more congenial, more evolved. I mean I’m perfectly happy being a man, but I find I have more in common with women.”

“Such as?”

He did hate her. He hated her royally. “The things we laugh at. The things we do with our free time. And, okay, I suppose you’ll want to talk about this—”

“I don’t want to talk about anything you don’t want to talk about.”

“Whatever. We also share sexual interests. I mean we like the same thing.”

“You’re homosexual?”

“I’m gay.” He smiled, determined to charm her, but she was impervious and vouchsafed no more than a wintry smile. “I told you. I’m a happy man.”

“Your sexuality isn’t a problem for you.”

“It never has been. It’s a constant source of delight. Not a day goes by when I don’t thank God. If anything I’m relieved. Especially now my friends are all having children.”

“You never wanted children.”

“Of course. Sometimes. Hats jokes that if she dies I can have hers. But no. The impulse came and went. There are more than enough children in the world and I’m not so obsessed with seeing myself reproduced. Besides, one of my nephews is the spitting image of me, which has taken care of that. I love my own company. I don’t think I’m selfish exactly but I’m self-sufficient.”

“What about settling down? You’re, what, thirty-five?”

“Thank you for that. I turned forty earlier this year. I have settled down. I have a satisfying job, a nice flat. I just happen to have settled down alone.”

“And watching all those girlfriends settled with their partners doesn’t make you want a significant other.”

“Oh. I have one of those. Sort of, I suppose. He’s really why I’m here. I made a promise to him. It was a joke really, but I told Harriet and—”

“Tell me about him.”

He paused. Glanced out at the view again. “Sorry,” he said. “It’s private.”

“Whatever you tell me—”

“—is in strictest confidence. Yes. I know. But we’ve barely met, you’re still a stranger to me and I’d rather not talk about him just now. It’s not a painful situation. He’s a lovely man. He makes me happy. But I didn’t come here to talk about him.”

A slight, attentive raising of her eyebrows asked, So what did you come to talk about?

“Shouldn’t we start with my childhood?” he said. “Isn’t that the usual thing?”

“If you like.”

“I warn you. I wasn’t abused. I wasn’t neglected. I love my parents and I loved my childhood. It was very, very happy.”

“Tell me about it.”