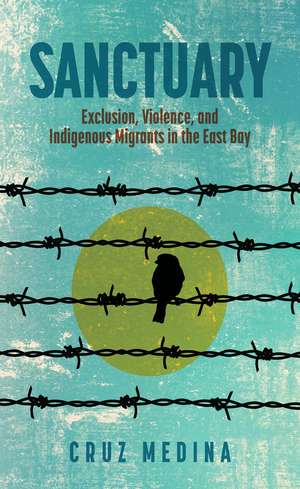

Sanctuary: Exclusion, Violence, and Indigenous Migrants in the East Bay: Global Latin/o Americas

Autor Cruz Medinaen Limba Engleză Paperback – 27 sep 2024

In Sanctuary, Cruz Medina presents a powerful counterstory to dominant narratives surrounding Latin American and Global South im/migration by bringing attention to the displacement of Indigenous Guatemalan Maya people who seek refuge in the United States. These migrants have exchanged gang and narcotrafficker violence for the dehumanizing and exclusionary rhetoric of US political leaders, militarized immigration enforcement, false promises of empowerment through literacy, and further displacement from gentrification. Medina combines decolonial critical race theory with autoethnography to examine white supremacist policies that impact US and transnational Indigenous populations who have been displaced by neocolonial projects of capitalism. Taking a Northern California community of migrants from Guatemala as a case study, Medina demonstrates the ways in which immigration policy and educational barriers exclude Indigenous migrant populations. He follows the community at the “Sanctuary”—a Spanish-speaking church in the East Bay Area that serves as a place of worship, English language instruction, and refuge for migrants. Medina assembles participant observations, interviews, surveys, and other data to provide points of entry into intersecting issues of immigration, violence, language, and property and to untangle aspects of citizenship, exclusion, and assumptions about literacy.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (1) | 194.88 lei 6-8 săpt. | |

| Ohio State University Press – 27 sep 2024 | 194.88 lei 6-8 săpt. | |

| Hardback (1) | 586.11 lei 6-8 săpt. | |

| Ohio State University Press – 27 sep 2024 | 586.11 lei 6-8 săpt. |

Preț: 194.88 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 292

Preț estimativ în valută:

37.30€ • 38.83$ • 31.52£

37.30€ • 38.83$ • 31.52£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 10-24 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780814259221

ISBN-10: 0814259227

Pagini: 168

Ilustrații: 1 b&w image

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Ohio State University Press

Seria Global Latin/o Americas

ISBN-10: 0814259227

Pagini: 168

Ilustrații: 1 b&w image

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Ohio State University Press

Seria Global Latin/o Americas

Recenzii

“Sanctuary is a piece of vital scholarship that teaches us how to maintain analytic focus at varying levels of the social scale to address the dangerous colonial nexus of power, while simultaneously introducing us to real people with real names and faces to whom we are fundamentally connected.” —Christina Cedillo, cofounder of the Journal of Multimodal Rhetorics

“Sanctuary is rhetorically engaging, emotionally honest, and intellectually accessible. Medina resists reducing complex findings to academically overdetermined and theoretically overwrought explanations. His rich description and grounded analysis open up new insights into questions about geopolitical sanctuary and spiritual sovereignty while humanizing both the author and the stakeholders.” —Michelle Hall Kells, author of Vicente Ximenes, LBJ’s Great Society, and Mexican American Civil Rights Rhetoric

“Cruz Medina’s Sanctuary is an expert uptake of storytelling and counterstorytelling. This work is a needed contribution to Central American rhetorics theorizing from lived reality that answers important calls by scholars such as Maritza E. Cárdenas and Joanna E. Sanchez-Avila for more content by, for, and about Central Americans.” —Aja Y. Martinez, author of Counterstory: The Rhetoric and Writing of Critical Race Theory

Notă biografică

Cruz Medina is Associate Professor of Rhetoric and Composition at Santa Clara University and faculty at Bread Loaf School of English. He is the author of Reclaiming Poch@ Pop: Examining the Rhetoric of Cultural Deficiency and coeditor of Racial Shorthand: Coded Discrimination Contested in Social Media.

Extras

This book is about the intersection of citizenship, violence, language, and property affecting migrants from Central America, aspects widely overlooked in the United States. As an examination of exclusionary rhetoric and policy in the US, this book takes us to Christa Olson’s call that “rhetoricians working in the United States ought not only look southward when we invoke American rhetorical history but also re-examine U.S. domestic rhetorics with an eye toward Latin America.” In my analysis of antimigrant policy in California affecting Central Americans in the US, I highlight the culpability of the US government’s interests in causing many to migrate north. But I also ask how the abuse of the visa system by companies in Silicon Valley reinforces categories of “good” and “bad” immigrants. This work builds on those works by rhetoric of immigration scholars who “have found that the meaning-making practices of immigrants can call into question issues of exclusion, including racialized hierarchies of citizenship and the criminalization of immigration.” These US interests contribute to and, in many cases, leave no other option than for migrants to risk their lives by making the journey to the US for an American Dream that many in the US regard critically and as mythical. However, a better life for many from Central America is finding refuge from violence and weakened governments following US intervention.

Many migrant students at the Sanctuary come from Guatemala, which has been directly and indirectly impacted by the political and economic interests of the US traceable back to the supposed spread of communism and continuing all the way up to the beans for Starbucks coffee. In addition to corporate interests in coffee and palm oil, the US government supported Guatemala’s government in an attempted genocide of Indigenous Mayas, officially referred to as a thirty-six-year “civil war.” A 1999 UN-backed Commission for Historical Clarification official document titled “Guatemala—Memory of Silence” reported that 83 percent of the victims of human rights violations were Indigenous Maya, and 93 percent of those responsible for human rights violations were the state and military. While the attempted genocide by the Guatemalan government is said to have concluded in 1996, the homicide rate in recent years has continued at rates near those of the “civil war,” fueled by the drug trade and US drug consumption. Migration from countries like Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador remain “inextricable from displacement created by US dirty wars backing death squads.” However, the public relations lauding of migrant labor in Silicon Valley is reserved for the mythical “good” migrants who are the founders and CEOs of multimillion-dollar start-ups, rather than those seeking refuge for the lives of their families.

Through working with adult Indigenous Maya Guatemalan students at the Sanctuary in the East Bay from 2013 to 2016, I came face-to-face with the layers of colonial influence and intervention that continued to impact my students’ lives. By colonial influence I speak of those in governmental power in Guatemala who identify primarily with European heritage and who have conspired with transnational business interests to the detriment of the predominantly Indigenous population. Unlike some of the volunteer teachers, I have Spanish languaging abilities that allowed me to translate aspects of lessons into Spanish, and while Spanish is yet another colonial language, it has been racialized as spoken by nonwhites with less power in the US. Still, the impact of learned generational secrecy and silence from the Guatemalan genocidal “civil war,” also referred to simply as “la violencia” (the violence), created divisions among the Indigenous people who speak twenty-one different Mayan languages, but also within those groups who speak the same Indigenous language. The majority of Mayas at the Sanctuary spoke Mam, although I learned that the majority Mam-speaking Mayas at the Sanctuary could not communicate with Mam speakers from other regions. Since the supposed end of the “civil war” in 1996, the proliferation of street gangs and narco-traffickers who inherited power from a weakened, ineffectual government continues to perpetuate a culture of mistrust. Many Indigenous Mayas learn from the land and sustain themselves on the corn, beans, and other agriculture they produce from their milpas. They have been displaced, however, through attempted genocide and transnational land grabs that threatened and continue to threaten their ways of life. In the US, these Mayas have exchanged gang and narco-trafficker violence for the dehumanizing rhetoric of political leaders, militarized immigration enforcement, promises of empowerment through literacy, and further displacement from (as a result of) gentrification. My book Sanctuary provides a point of entry into the intersectional issue of immigration, using interactions, interviews, and survey data from Maya adult students in the East Bay of Northern California. My intent is to untangle how language and policy serve to exclude those racialized by language and Indigeneity from citizenship, education, and property through critical race theory and decolonial frameworks that center the stories and lived experiences of people of color and Indigenous populations.

Many migrant students at the Sanctuary come from Guatemala, which has been directly and indirectly impacted by the political and economic interests of the US traceable back to the supposed spread of communism and continuing all the way up to the beans for Starbucks coffee. In addition to corporate interests in coffee and palm oil, the US government supported Guatemala’s government in an attempted genocide of Indigenous Mayas, officially referred to as a thirty-six-year “civil war.” A 1999 UN-backed Commission for Historical Clarification official document titled “Guatemala—Memory of Silence” reported that 83 percent of the victims of human rights violations were Indigenous Maya, and 93 percent of those responsible for human rights violations were the state and military. While the attempted genocide by the Guatemalan government is said to have concluded in 1996, the homicide rate in recent years has continued at rates near those of the “civil war,” fueled by the drug trade and US drug consumption. Migration from countries like Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador remain “inextricable from displacement created by US dirty wars backing death squads.” However, the public relations lauding of migrant labor in Silicon Valley is reserved for the mythical “good” migrants who are the founders and CEOs of multimillion-dollar start-ups, rather than those seeking refuge for the lives of their families.

Through working with adult Indigenous Maya Guatemalan students at the Sanctuary in the East Bay from 2013 to 2016, I came face-to-face with the layers of colonial influence and intervention that continued to impact my students’ lives. By colonial influence I speak of those in governmental power in Guatemala who identify primarily with European heritage and who have conspired with transnational business interests to the detriment of the predominantly Indigenous population. Unlike some of the volunteer teachers, I have Spanish languaging abilities that allowed me to translate aspects of lessons into Spanish, and while Spanish is yet another colonial language, it has been racialized as spoken by nonwhites with less power in the US. Still, the impact of learned generational secrecy and silence from the Guatemalan genocidal “civil war,” also referred to simply as “la violencia” (the violence), created divisions among the Indigenous people who speak twenty-one different Mayan languages, but also within those groups who speak the same Indigenous language. The majority of Mayas at the Sanctuary spoke Mam, although I learned that the majority Mam-speaking Mayas at the Sanctuary could not communicate with Mam speakers from other regions. Since the supposed end of the “civil war” in 1996, the proliferation of street gangs and narco-traffickers who inherited power from a weakened, ineffectual government continues to perpetuate a culture of mistrust. Many Indigenous Mayas learn from the land and sustain themselves on the corn, beans, and other agriculture they produce from their milpas. They have been displaced, however, through attempted genocide and transnational land grabs that threatened and continue to threaten their ways of life. In the US, these Mayas have exchanged gang and narco-trafficker violence for the dehumanizing rhetoric of political leaders, militarized immigration enforcement, promises of empowerment through literacy, and further displacement from (as a result of) gentrification. My book Sanctuary provides a point of entry into the intersectional issue of immigration, using interactions, interviews, and survey data from Maya adult students in the East Bay of Northern California. My intent is to untangle how language and policy serve to exclude those racialized by language and Indigeneity from citizenship, education, and property through critical race theory and decolonial frameworks that center the stories and lived experiences of people of color and Indigenous populations.

Cuprins

List of Illustrations Preface Scarred Family Trees Acknowledgments Introduction Chapter 1 Citizenship, Economies of Exclusion, and Tech Money Chapter 2 Decolonizing Immigration with Critical Race Theory Chapter 3 Violence and the Legacy of Colonial Genocide Chapter 4 Sanctuary Struggle, Linguistic Discrimination, and Indigenous Displacement Chapter 5 Volunteer Literacy Teacher Counterstory Chapter 6 Concluding a Story without an End Appendix Survey Questions Works Cited Index

Descriere

Brings Indigenous migrant populations to the fore of intersecting issues of immigration, violence, language, and property to cast light on citizenship, literacy, and exclusion in the United States.