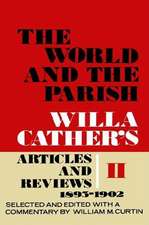

Sapphira And The Slave Girl

Autor Willa Catheren Limba Engleză Paperback – 8 iul 2019

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (3) | 55.35 lei 6-8 săpt. | |

| Vintage Books USA – 30 noi 2010 | 82.29 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| Little Brown Book Group – 6 sep 2006 | 55.35 lei 6-8 săpt. | |

| Lector House – 8 iul 2019 | 73.80 lei 6-8 săpt. | |

| Hardback (1) | 559.13 lei 6-8 săpt. | |

| Nebraska – iul 2009 | 559.13 lei 6-8 săpt. |

Preț: 73.80 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 111

Preț estimativ în valută:

14.12€ • 15.39$ • 11.90£

14.12€ • 15.39$ • 11.90£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 23 aprilie-07 mai

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9789353440718

ISBN-10: 9353440718

Pagini: 128

Dimensiuni: 156 x 234 x 8 mm

Greutate: 0.21 kg

Editura: Lector House

ISBN-10: 9353440718

Pagini: 128

Dimensiuni: 156 x 234 x 8 mm

Greutate: 0.21 kg

Editura: Lector House

Notă biografică

Willa Cather was born near Winchester, Virginia, in 1873. When she was ten years old, her family moved to the prairies of Nebraska, later the setting for a number of her novels. At the age of twenty-one, she graduated from the University of Nebraska, and she spent the next few years doing newspaper work and teaching high school in Pittsburgh. In 1903, her first book, April Twilights, a collection of poems, was published, and two years later The Troll Garden, a collection of stories, appeared in print. After the publication of her first novel, Alexander’s Bridge, in 1912, Cather devoted herself full time to writing, and over the years she completed eleven more novels (including O Pioneers!, My Ántonia, The Professor’s House, and Death Comes for the Archbishop), four collections of short stories, and two volumes of essays. Cather won the Pulitzer Prize for One of Ours in 1923. She died in 1947.

Extras

Book I

I

The Breakfast Table, 1856.

Henry Colbert, the miller, always breakfasted with his wife — beyond that he appeared irregularly at the family table. At noon, the dinner hour, he was often detained down at the mill. His place was set for him; he might come, or he might send one of the mill-hands to bring him a tray from the kitchen. The Mistress was served promptly. She never questioned as to his whereabouts.

On this morning in March 1856, he walked into the dining-room at eight o'clock, —came up from the mill, where he had been stirring about for two hours or more. He wished his wife good-morning, expressed the hope that she had slept well, and took his seat in the high-backed armchair opposite her. His breakfast was brought in by an old, white-haired coloured man in a striped cotton coat. The Mistress drew the coffee from a silver coffee urn which stood on four curved legs. The china was of good quality (as were all the Mistress's things); surprisingly good to find on the table of a country miller in the Virginia backwoods. Neither the miller nor his wife was native here: they had come from a much richer county, east of the Blue Ridge. They were a strange couple to be found on Back Creek, though they had lived here now for more than thirty years.

The miller was a solid, powerful figure of a man, in whom height and weight agreed. His thick black hair was still damp from the washing he had given his face and head before he came up to the house; it stood up straight and busy because he had run his fingers through it. His face was full, square, and distinctly florid; a heavy coat of tan made it a reddish brown, like an old port. He was clean-shaven, —unusual in a man of his age and station. His excuse was that a miller's beard got powdered with flour-dust, and when the sweat ran down his face this flour got wet and left him with a bear full of dough. His countenance bespoke a man of upright character, straightforward and determined. It was only his eyes that were puzzling; dark and grave, set far back under a square, heavy brow. Those eyes, reflective, almost dreamy, seemed out of keeping with the simple vigour of his face. The long lashes would have been a charm in a woman.

Colbert drove his mill hard, gave it his life, indeed. He was noted for fair dealing, and was trusted in a community to which he had come a stranger. Trusted, but scarcely liked. The people of Back Creek and Timber Ridge and Hayfield never forgot that he was not one of themselves. He was silent and uncommunicative (a trait they didn't like), and his lack of a Southern accent amounted almost to a foreign accent. His grandfather had come over from Flanders. Henry was born in Loudoun County and had grown up in a neighbourhood of English settlers. He spoke the language as they did, spoke it clearly and decidedly. This was not, on Back Creek, a friendly way of talking.

His wife also spoke differently from the Back Creek people; but they admitted that a woman and an heiress had a right to. Her mother had come out from England — a fact she never forgot. How these two came to be living at the Mill Farm is a long story — too long for a breakfast-table story.

The miller drank his first cup of coffee in silence. The old black man stood behind the Mistress's chair.

"You may go, Washington," she said presently. While she drew another cup of coffee from the urn with her very plump white hands, she addressed her husband: "Major Grimwood stopped by yesterday, on his way to Romney. You should have come up to see him."

"I couldn't leave the mill just then. I had customers who had come a long way for their grain," he replied gravely.

"If you had a foreman, as everyone else has, you would have time to be civil to important visitors."

"And neglect my business? Yes, Sapphira, I know all about these foremen. That is how it is done back in Loudoun County. The boss tells the foreman, and the foreman tells the head nigger, and the head nigger passes it on. I am the first miller who has ever made a living in these parts."

"A poor one at that, we must own," said his wife with an indulgent chuckle. "And speaking of niggers, Major Grimwood tells me his wife is in need of a handy girl just now. He knows my servants are well trained, and would like to have one of them."

"He must know you train your servants for your own use. We don't sell our people. You might ring for some more bacon. I seem to feel hungry this morning."

She rang a little clapper bell. Washington brought the bacon and again took his place behind his mistress's large, cumbersome chair. She had been sitting in a muse while he served. Now, without speaking to him, she put out her plump hand in the direction of the door. The old man scuttled off in his flapping slippers.

"Of course we don't sell our people," she agreed mildly. "Certainly we would never offer any for sale. But to oblige friends is a different matter. And you've often said you don't want to stand in anybody's way. To live in Winchester, in a mansion like the Grimwoods' —any darky would jump at the chance."

"We have none to spare, except such as Major Grimwood wouldn't want. I will tell him so."

Mrs. Colbert went on in her bland, considerate voice: "There is my Nancy, now. I could spare her quite well to oblige Mrs. Grimwood, and she could hardly find a better place. It would be a fine opportunity for her."

The miller flushed a deep red up to the roots of his thick hair. His eyes seemed to sink farther back under his heavy brow as he looked directly at his wife. His look seemed to say: I see through all this, see to the bottom. She did not meet his glance. She was gazing thoughtfully at the coffee urn.

Her husband pushed back his plate. "Nancy least of all! Her mother is here, and old Jezebel. Her people have been in your family for four generations. You haven't trained Nancy for Mrs. Grimwood. She stays here."

The icy quality, so effective with her servants, came into Mrs. Colbert's voice as she answered him.

"It's nothing to get flustered about, Henry. As you say, her mother and grandmother were all Dodderidge niggers. So it seems to me I ought to be allowed to arrange Nancy's future. Her mother would approve. She knows that a proper lady's maid can never be trained out here in this rough country."

The miller's frown darkened. "You can't sell her without my name to the deed of sale, and I will never put it there. You never seemed to understand how, when we first moved up here, your troop of niggers was held against us. This isn't a slave-owning neighbourhood. If you sold a good girl like Nancy off to Winchester, people hereabouts would hold it against you. They would say hard things."

Mrs. Colbert's small mouth twisted. She gave her husband an arch, tolerant smile. "They have talked before, and we've survived. They surely talked when black Till bore a yellow child, after two of your brothers had been hanging round here so much. Some fixed it on Jacob, and some on Guy. Perhaps you have a kind of family feeling about Nancy?"

"You know well enough, Sapphira, it was that painter from Baltimore."

"Perhaps. We got portraits out of him, anyway, and maybe we got a smart yellow girl into the bargain." Mrs. Colbert laughed discreetly, as if the idea amused her and rather pleased her. "Till was within her rights, seeing she had to live with old Jeff. I never hectored her about it."

The miller rose and walked toward the door.

"One moment, Henry." As he turned, she beckoned him back. "You don't really mean you will not allow me to dispose of one of my own servants? You signed when Tom and Jake and Ginny and the others went back."

"Yes, because they were going back among their own kin, and to the country they were born in. But I'll never sign for Nancy."

Mrs. Colbert's pale-blue eyes followed her husband as he went out of the door. Her small mouth twisted mockingly. "Then we must find some other way," she said softly to herself.

Presently she rang for old Washington. When he came she said nothing, being lost in thought, but put her hands on the arms of the square, high-backed chair in which she sat. The old man ran to open two doors. Then he drew his mistress's chair away from the table, picked up a cushion on which her feet had been resting, tucked it under his arm, and gravely wheeled the chair, which proved to be on castors, out of the dining-room, down the long hall, and into Mrs. Colbert's bedchamber.

The Mistress ahd dropsy and was unable to walk. She could still stand erect to receive visitors: her dresses touched the floor and concealed the deformity of her feet and ankles. She was four years older than her husband — and hated it. This dropsical affliction was all the more cruel in that she had been a very active woman, and had managed the farm as zealously as her husband managed his mill.

I

The Breakfast Table, 1856.

Henry Colbert, the miller, always breakfasted with his wife — beyond that he appeared irregularly at the family table. At noon, the dinner hour, he was often detained down at the mill. His place was set for him; he might come, or he might send one of the mill-hands to bring him a tray from the kitchen. The Mistress was served promptly. She never questioned as to his whereabouts.

On this morning in March 1856, he walked into the dining-room at eight o'clock, —came up from the mill, where he had been stirring about for two hours or more. He wished his wife good-morning, expressed the hope that she had slept well, and took his seat in the high-backed armchair opposite her. His breakfast was brought in by an old, white-haired coloured man in a striped cotton coat. The Mistress drew the coffee from a silver coffee urn which stood on four curved legs. The china was of good quality (as were all the Mistress's things); surprisingly good to find on the table of a country miller in the Virginia backwoods. Neither the miller nor his wife was native here: they had come from a much richer county, east of the Blue Ridge. They were a strange couple to be found on Back Creek, though they had lived here now for more than thirty years.

The miller was a solid, powerful figure of a man, in whom height and weight agreed. His thick black hair was still damp from the washing he had given his face and head before he came up to the house; it stood up straight and busy because he had run his fingers through it. His face was full, square, and distinctly florid; a heavy coat of tan made it a reddish brown, like an old port. He was clean-shaven, —unusual in a man of his age and station. His excuse was that a miller's beard got powdered with flour-dust, and when the sweat ran down his face this flour got wet and left him with a bear full of dough. His countenance bespoke a man of upright character, straightforward and determined. It was only his eyes that were puzzling; dark and grave, set far back under a square, heavy brow. Those eyes, reflective, almost dreamy, seemed out of keeping with the simple vigour of his face. The long lashes would have been a charm in a woman.

Colbert drove his mill hard, gave it his life, indeed. He was noted for fair dealing, and was trusted in a community to which he had come a stranger. Trusted, but scarcely liked. The people of Back Creek and Timber Ridge and Hayfield never forgot that he was not one of themselves. He was silent and uncommunicative (a trait they didn't like), and his lack of a Southern accent amounted almost to a foreign accent. His grandfather had come over from Flanders. Henry was born in Loudoun County and had grown up in a neighbourhood of English settlers. He spoke the language as they did, spoke it clearly and decidedly. This was not, on Back Creek, a friendly way of talking.

His wife also spoke differently from the Back Creek people; but they admitted that a woman and an heiress had a right to. Her mother had come out from England — a fact she never forgot. How these two came to be living at the Mill Farm is a long story — too long for a breakfast-table story.

The miller drank his first cup of coffee in silence. The old black man stood behind the Mistress's chair.

"You may go, Washington," she said presently. While she drew another cup of coffee from the urn with her very plump white hands, she addressed her husband: "Major Grimwood stopped by yesterday, on his way to Romney. You should have come up to see him."

"I couldn't leave the mill just then. I had customers who had come a long way for their grain," he replied gravely.

"If you had a foreman, as everyone else has, you would have time to be civil to important visitors."

"And neglect my business? Yes, Sapphira, I know all about these foremen. That is how it is done back in Loudoun County. The boss tells the foreman, and the foreman tells the head nigger, and the head nigger passes it on. I am the first miller who has ever made a living in these parts."

"A poor one at that, we must own," said his wife with an indulgent chuckle. "And speaking of niggers, Major Grimwood tells me his wife is in need of a handy girl just now. He knows my servants are well trained, and would like to have one of them."

"He must know you train your servants for your own use. We don't sell our people. You might ring for some more bacon. I seem to feel hungry this morning."

She rang a little clapper bell. Washington brought the bacon and again took his place behind his mistress's large, cumbersome chair. She had been sitting in a muse while he served. Now, without speaking to him, she put out her plump hand in the direction of the door. The old man scuttled off in his flapping slippers.

"Of course we don't sell our people," she agreed mildly. "Certainly we would never offer any for sale. But to oblige friends is a different matter. And you've often said you don't want to stand in anybody's way. To live in Winchester, in a mansion like the Grimwoods' —any darky would jump at the chance."

"We have none to spare, except such as Major Grimwood wouldn't want. I will tell him so."

Mrs. Colbert went on in her bland, considerate voice: "There is my Nancy, now. I could spare her quite well to oblige Mrs. Grimwood, and she could hardly find a better place. It would be a fine opportunity for her."

The miller flushed a deep red up to the roots of his thick hair. His eyes seemed to sink farther back under his heavy brow as he looked directly at his wife. His look seemed to say: I see through all this, see to the bottom. She did not meet his glance. She was gazing thoughtfully at the coffee urn.

Her husband pushed back his plate. "Nancy least of all! Her mother is here, and old Jezebel. Her people have been in your family for four generations. You haven't trained Nancy for Mrs. Grimwood. She stays here."

The icy quality, so effective with her servants, came into Mrs. Colbert's voice as she answered him.

"It's nothing to get flustered about, Henry. As you say, her mother and grandmother were all Dodderidge niggers. So it seems to me I ought to be allowed to arrange Nancy's future. Her mother would approve. She knows that a proper lady's maid can never be trained out here in this rough country."

The miller's frown darkened. "You can't sell her without my name to the deed of sale, and I will never put it there. You never seemed to understand how, when we first moved up here, your troop of niggers was held against us. This isn't a slave-owning neighbourhood. If you sold a good girl like Nancy off to Winchester, people hereabouts would hold it against you. They would say hard things."

Mrs. Colbert's small mouth twisted. She gave her husband an arch, tolerant smile. "They have talked before, and we've survived. They surely talked when black Till bore a yellow child, after two of your brothers had been hanging round here so much. Some fixed it on Jacob, and some on Guy. Perhaps you have a kind of family feeling about Nancy?"

"You know well enough, Sapphira, it was that painter from Baltimore."

"Perhaps. We got portraits out of him, anyway, and maybe we got a smart yellow girl into the bargain." Mrs. Colbert laughed discreetly, as if the idea amused her and rather pleased her. "Till was within her rights, seeing she had to live with old Jeff. I never hectored her about it."

The miller rose and walked toward the door.

"One moment, Henry." As he turned, she beckoned him back. "You don't really mean you will not allow me to dispose of one of my own servants? You signed when Tom and Jake and Ginny and the others went back."

"Yes, because they were going back among their own kin, and to the country they were born in. But I'll never sign for Nancy."

Mrs. Colbert's pale-blue eyes followed her husband as he went out of the door. Her small mouth twisted mockingly. "Then we must find some other way," she said softly to herself.

Presently she rang for old Washington. When he came she said nothing, being lost in thought, but put her hands on the arms of the square, high-backed chair in which she sat. The old man ran to open two doors. Then he drew his mistress's chair away from the table, picked up a cushion on which her feet had been resting, tucked it under his arm, and gravely wheeled the chair, which proved to be on castors, out of the dining-room, down the long hall, and into Mrs. Colbert's bedchamber.

The Mistress ahd dropsy and was unable to walk. She could still stand erect to receive visitors: her dresses touched the floor and concealed the deformity of her feet and ankles. She was four years older than her husband — and hated it. This dropsical affliction was all the more cruel in that she had been a very active woman, and had managed the farm as zealously as her husband managed his mill.

Descriere

Descriere de la o altă ediție sau format:

Willa Cather's twelfth and final novel, Sapphira and the Slave Girl is her most intense fictional engagement with political and personal conflict.

Willa Cather's twelfth and final novel, Sapphira and the Slave Girl is her most intense fictional engagement with political and personal conflict.

Cuprins

Preface

Sapphira and the Slave Girl

Acknowledgments

Historical Apparatus:

Historical Essay

Illustrations following page 000

Explanatory Notes

Textual Apparatus:

Textual Essay

Appendixes to the Textual Essay

Emendations

Notes on Emendations

Table of Rejected Substantives

Word Division

Sapphira and the Slave Girl

Acknowledgments

Historical Apparatus:

Historical Essay

Illustrations following page 000

Explanatory Notes

Textual Apparatus:

Textual Essay

Appendixes to the Textual Essay

Emendations

Notes on Emendations

Table of Rejected Substantives

Word Division

Recenzii

"The most significant achievement of this edition is that it will help scholars at every level understand the novel as evidence of Cather's involvement in public intellectual debates of her era, as well as of her complex personal involvement with the interrelation of memory, aesthetics, loss, and aging."—Robin Hackett, Great Plains Quarterly